At its most basic level, feminism is the belief in women’s full social, economic, and political equality. Feminism emerged mostly in response to Western traditions that limited women’s rights, but feminist thinking has many forms and variations worldwide (Brunell & Burkett, n.d.).

The three waves of feminism in America brought in a lot of change, progress and development, for the US. Its shadow fell upon the rest of the world, fuelling the sentiment of oppression and empowerment amongst women. Betty Friedan, the author of the Feminine Mystique and the pioneer of the second wave of the feminist movement in America, advocated for women’s rights in the context that women who solely focus on being a housewife or mothers were left with a void and faced a problem that had no name, the mystique itself was of such nature (Friedan, 2010).

Friedan (2010), through some primary and multiple secondary sources, concluded that women failed to recognize their individuality, purpose, and meaning in life owing to their obsession with chasing the mystique and trying to be the perfect embodiment of a woman that society and especially men expected. The book encapsulates Friedan’s pejorative of the American housewife, and her struggle to find fulfilment.

According to Friedan, women should look at housework as something they can get done quickly, she goes on to say that for women of that time, the work of the house was never enough, and never was it too much originally (Friedan, 2010, p. 203).

Domesticity started from a woman’s 20s, her education was of less priority and her career was non-existent, to begin with. Friedan emphasized that women were engineered to become more feminine through their role as housewives, essentially indicating that the role of the homemaker was not need-based but a void-filling mechanism for the woman to fill her time (Friedan, 2010, p. 207).

The real cause of frustration for women, she states, is the emptiness of the housewife’s role. Wherein she purposefully tries to immerse herself within housework because she doesn’t know what to do otherwise. She goes on to say that if women had pursued a career and established an identity outside of their home, they would have ascribed housewife work the same position that men ascribed to cars or gardens and relative things like these (Friedan, 2010, p. 196). This does raise a question, of whether it is necessary for women, men or anyone to not have their identity rooted in their family or their home.

In its very essence, the feminine mystique sheds light on the American woman’s plight and aims to convince how she has trapped herself in the illusion of being the perfect woman through the appraisal of her husband and family (Friedan, 2010). Friedan (2010) explores the realms of the American culture where it was expected of women to be fragile and dense to seem feminine, women essentially gave their identity in trade for the happiness that the mystique promised.

The narrative of domesticity that Friedan proposes is that of a malicious and pain-ridden culture where women are endlessly trapped in fruitless menial labor with no impact on the world, and hence no recognition of the housewife whatsoever. Young women and little girls were engineered to think of being a housewife as their destination with plentiful bounties and endless happiness. This led to the endless pursuit of the feminine manifestation of the mystique. The housewife is stuck in the crude cycle of domesticity and leads a purposeless life (Friedan, 2010).

Through this paper, we aim to study this concept of domesticity that Friedan observed in the US and establish a narrative of Indian women and their perception of domesticity (Friedan, 2010).

To start with, domesticity has been more than a simple routine needs-based work in Indian civilization. While referred to as ‘grihasthi’, the word originates from the ‘ashrama’ system (Sharma. A, 2007, p. 18). The housemakers of India have a sacred position within the household, although highly valued they do share their fair share of problems within the Indian context.

Housemakers have contributed a significant part to society, typically a homemaker is involved in the administration and care of the home and the family. She manages micro to major work involved in the house wherein it could be as small as cooking food to as huge as instilling good values within her children and sustaining relationships within the family. With time, the description of housework and homemaker has changed depending on the dynamic family structures, functions, and norms. In such a case, we could derive a generalized definition of a homemaker.

In the Indian context, domesticity has an added integral component of festivals, unlike other cultures. Festivals in India have been known to be a time of joy, bonding, and worshiping. Festivals are essentially the epitome of wisdom, learning, happiness, and are the fine imprints of experiences imparted from one generation to the next (Lall, 1933).

In the Indian context, focusing on the feminine is parallel to focusing on the divine and the spiritual. Goddesses are a representation of the feminine within the individual and personify much more than sole femininity. Festivals have thus been an irreplaceable pervasive annual custom that families anticipate and prepare together for. They constitute the very fabric of Indian society and the Indian family.

Festivals are women-led, with many of the rituals and rites essentially requiring the woman’s presence for them to commence. This goes without saying that men are deemed just as important in their celebration, however, women lead the festivals within the social and cultural milieu. Through this paper, we want to know whether festivals have had far more reaching effects owing to their metaphysical spiritual nature.

Apart from that, the question of contributory factors towards empowerment of women put pressure on the fact that perhaps for India, the factors could be varied owing to the social fabric and religious background of the demographic.

Women empowerment in itself is varied in its definition depending on the focus areas within that demographic. Using thematic analysis, we want to identify a definition of empowerment for the women of Maharashtra and face the question of whether Friedan’s conceptualization of empowerment applies within the Indian context.

The focus of this study is to delve into the lives of women who are employed or are/were full-time homemakers. To understand their role within the home system and their views on the concept of Friedan’s domesticity. In the end, we expect a plethora of insights congregated into a coding system using thematic analysis to understand the patterns from the interviews with different women, across the three generations.

Review of Literature

The first wave of feminism dates back to the 19th century with the Suffrage Movement and has focused on different gender discrimination issues across the three waves of feminist movements. Initially started in the United States and the United Kingdom, this movement gained traction worldwide due to its basic notion of oppression and imbalance between the two focused genders of men and women. Across time, women have fought the disparity within their own country to establish their identity within the societal framework (Brunell & Burkett, n.d.).

Betty Friedan’s notable contributions towards the second wave of the feminist movement are well known. Through her book, “The Feminine Mystique,” Freidan explored how middle-class suburban American women had lost their connection with themselves due to the lure of the feminine mystique. Friedan emphasized how American women are riddled with “the problem that has no name” (Friedan, 2010).

In 1957, through a survey of 200 women from her college, Friedan found that the American women were nowhere near the perfect picture that American culture envisaged them to be (Friedan, 2010, p. 01). In search for the origin of the feminine mystique, Friedan found herself and other American women leading dissatisfied and purposeless lives.

According to Friedan, popular media, magazines, books, and articles all talked about how to be the perfect wife and mother and nothing more than that (Friedan, 2010, p. 05). Women were engineered to fantasize about this perfect life, with a great house, five children, and a good husband (Friedan, 2010, p. 08). Education and work took a backseat; wherein women went to college purely to fulfill the essential criteria and only ever dreamed of getting a husband. Although women did work, they were primarily part-time “non-career” oriented jobs (Friedan, 2010, p. 07).

In the book by Friedan (2010), all of this was because women were taught that genuinely feminine women shouldn’t dive deep into careers, higher education, or even politics. Women were exposed to such media and influence from an early age and adopted this mystique to become the perfect woman. Women were actively pursuing a husband, says Friedan; they made this their top priority. The problem of no name made women feel lifeless, mediocre, and ambitionless.

Freidan observed that the American woman’s identity was based entirely on her environment; she had no private image. Instead, the sole indicator of her identity was the public. The woman’s public image constituted the portrayal of materialistic objects that were commercialized by the media and television (Friedan, 2010, p. 53).

Women didn’t have the choice to be themselves; they had to ascribe to the feminine identity set by the public image. Due to this, they experienced a role identity crisis. (Friedan, 2010, p. 57). Freidan put forth a thesis that women who didn’t “grow” thus succumbed to the feminine mystique (Friedan, 2010, p. 58).

Freidan categorizes women into “high dominance” and “low dominance” types. High dominance was associated with women who were not conventionally “feminine,” they were strong, purposeful, and made their own life rules. These women wanted to be treated like a person, not a “woman.” Whereas low dominance women would not be rebellious, they were bound to conventional ethics and did what authorities and religion advised them to do (Friedan, 2010, p. 257).

In Friedan’s book, a housewife focuses solely on the repair and maintenance of the house; she takes care of her children and her perfect husband; she is endowed with dull and low-grade house chores and family management, which Friedan states can be handled by an 8-year-old as well. (Friedan, 2010, p. 208). According to Friedan, “Housewifery” in its entire essence, is a purely dull job that requires no use of intellectual power, rendering the housewife to be like a blue-collar worker in the factory contributing the least to progress within the society (Friedan, 2010).

According to Freidan, the role of the housewife was empty itself. Freidan proposed that the number of times women took to complete their housework was inversely related to the challenge of the other work. Suggesting that women purposely tried to fill their time or void with expansive housework because they had nothing better to do. Because they thought that was all they were supposed to do (Friedan, 2010, p. 196).

Freidan’s conceptualization of domesticity and being a housewife speaks to her experience of the time and multiple American women. Friedan (2010) believed that being a housewife was not a satisfying role for women. She found that several women complained of feeling empty in their roles. However, Freidan recognizes that homemakers might be happy and content with their lives. She says that the feeling of “aliveness,” wherein human ability is used to the maximum, is not the same as being happy. Hence, solely being a housewife was not okay in any context.

Throughout her book, Freidan (2010) emphasizes the constant degradation of women and the problems they face in their lives. Within its realms, The Feminine Mystique was pretty apt for its crowd and has assisted in the change for US’s feminist movement (Friedan, 2010).

The very aspect of feminism is the typical expression of oppression felt by women. But the experiences and revolutionary acts of women within the US won’t mirror those within other distinct demographic cultures. India is a country with collectivistic social structures and ripe with ancient heritage. Indeed, it has its path to navigate when it comes to an understanding of the concept of feminism, woman empowerment, and domesticity within the Indian demographic.

Our focus in this paper is to peer into the lives of Indian women and to gauge their notion of feminism and how they personalize it. We will be doing this through multiple lenses, one that of the concept of domesticity and other the essence of festivals within Indian culture. Unlike Freidan’s description of domesticity within the US, in India, it was better referred to by the term “grihasthi.”

In the Vedic context, marriage goes beyond a contractual decision between two people. For every individual, the goal of life is to achieve the four purusharthas, namely artha (wealth), kaama (cultural life), dharma (duty), and Moksha (spiritual freedom). The married couple goes through the strife of life together to pursue the purusharthas. Hence, marriage and grihasthi transcend the physical realm and hold their very essence within the spiritual realm. Grihashti encapsulates much more than domesticity, housework being one of its aspects, grihasthi expands to fill the socio-cultural and spiritual unity between the wife and the husband (Chakraborty. A, 2015, p. 36).

In India, grihasthi has been the term referred to when a couple gets married, entering the grihasthi stage of life. A gruhini is also called a ‘dharampatni’, indicating her role within the family and the household is much more than maintaining the house (Kumar, S. P. 1998, p. 145). The gruhini (wife) and the grihastha (husband) will carry their home and family together. Of the four ashrama systems, grihasthi was the most crucial in contributing to societal growth, cohesive social structures, and maintaining the community within one’s region. Indian women have become accustomed to the profound cultural changes that happened with time, yet grihasthi is still used to refer to an individual’s married and domestic life (Chakraborty. A, 2015, p. 31,36, 38). Can an Indian housewife, a gruhini, then be viewed as “empowered” from a feministic viewpoint?

Friedan (2010), however, deemed every homemaker to be dull, purposeless and lost in life. She claimed that no homemaker could ever be happy in their role. This, however, may not hold water within the Indian context. Owing to the history of grihasthi in India, there’s much more to be found on the grounds of women leading happy and active lives. Women empowerment for Indian homemakers could be much different than what Freidan envisaged for American homemakers.

Within the Indian demographic, feminism has been an integral part of its culture rooted in its theological background. Hindu goddesses have been a source of strength, love, knowledge, resilience, and courage. They are extensively worshiped by men and women alike due to these attributes.

The fearless actions and stories of these Indian goddesses, revolutionary Indian women, are represented through festivals. Also known as ‘San’ in the Marathi language, festivals have been celebrated ever since the existence of Indian society. Festivals have been a platform for people to commemorate the good times and gain hope and happiness for the present and the future. In India, each festival entails a series of events like pooja, fasting, vratas, family gathering, community gathering, and celebrations. They have been a way for people to reconnect with their virtues, friends, relatives, and close members (Lall, 1933).

Festivals have been a source of validating the individual’s social needs and have given them a sense of belonging. An individual’s identity is inevitably connected to their social space (Jaeger, K., & Mykletun; R. J. 2013, p.214). The organization and process involved in the festivals require the involvement of the entire group, encouraging group spirit and interpersonal bonding. Festivals, in part, may impact an individual’s psychological and emotional need to connect and belong within the social sphere (Jaeger, K., & Mykletun; R. J. 2013, p.214). Hence, especially in the Indian context, festivals are not only a theological manifestation that people have been traditionally celebrating. They also contribute to the active social community and feeling of togetherness within society.

Women have been the carriers of festivals and are majorly involved in their preparation, organization, and execution. Women are in charge of planning for festivals; they delegate the work within their family and oversee the proper celebration of festivals (Pandey. K, 2018, p. 119). Hence, women have been an irreplaceable entity within the realm of celebration of festivals.

This paper aims to explore the cultural significance of this concept of grihasthi within women of Maharashtra. We are also pursuing the question of how grihasthi has come to be perceived amongst these women. There seems to be sparse literature on how festivals contribute to a woman’s life; our research aims to fill that gap. Festivals, in part, have also been a significant aspect in a woman’s life, inviting the curiosity of whether they can be an aspect of empowerment for women.

Women empowerment has been used interchangeably with feminism owing to their similar meaning. While the history of feminism has been rooted in transformational phases, “empowerment” is an action term that gives the essence of women becoming stronger and having authority over their lives. Hence, women empowerment has been conjured as a more relative term to our focus in the research (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.).

In terms of woman empowerment, we will be finding out every woman’s perspective and definition on the same through their lived experiences. This will shed light on the possible parameters for empowerment in Maharashtrian women.

Methodology

The research focused on the qualitative exploration of the perspectives of women in identification with Friedan’s feminism and the perceived role of festivals. The sample size consisted of 8 participants, selected to be the women from Maharashtra with age groups from 20 to 65+. The samples were divided into three groups depending on the age: 20 to 35 being the first group, 40 to 60 years being the second group, last being 65 years and above. This division was made in order to gain perspectives from different generations and get a wholesome idea of the culture and varying notions. The population was distributed into east, central, and western Maharashtra. The sample was selected using purposive and snowball sampling methodology. The qualitative interviews were in a semi-structured format. Apart from the actual sample, the study also interviewed a lot who were people from the grass-root level, subject, and field experts in order to gain in-depth insight, understanding about the domain.

The participants were briefed about the study in detail and the participation was voluntary. The study involved no risks and benefits for participants. The participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any point of time if they wish to.

Results

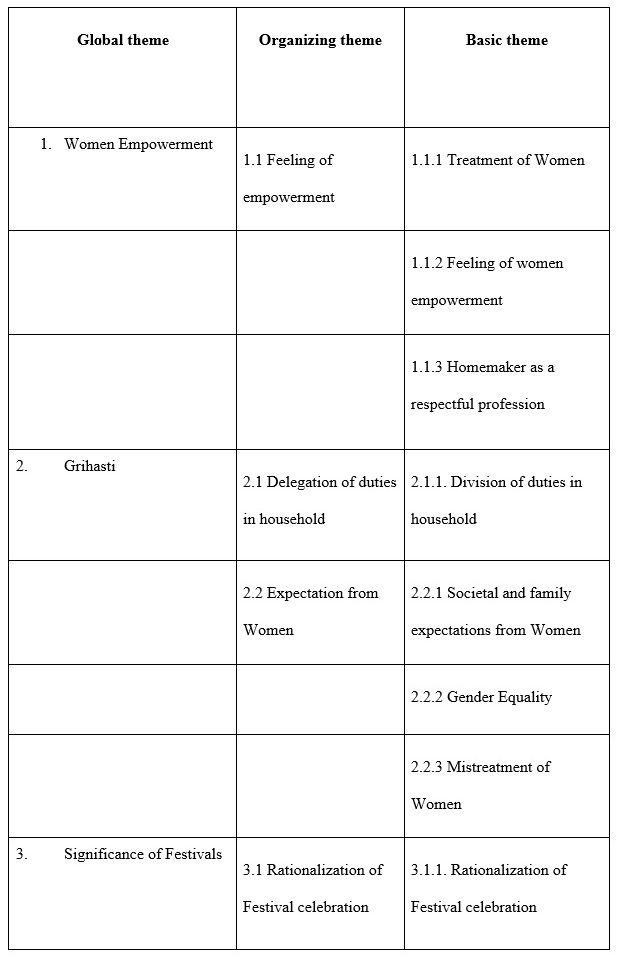

Table 1.

Themes that emerged from the transcripts

Note: These themes are the one emerged from the analysis and coding of interviews from the sample.

Discussion

Thematic analysis has identified three global themes through the interview transcripts: Women empowerment, Grihasti (household), Significance of Festivals. The organizing themes and basic themes have been laid out accordingly.

- Women Empowerment

Empowerment can be described as the perceived autonomy of an individual to control the factors that affect their lives (Mokta, 2014).

Empowerment is a multidimensional and active process that gives women the capacity to realize their power and identity (Bayeh, 2016). It is a concept that originated in the west and has been implemented similarly across the whole world. One of the most dominant ideas of empowerment was propagated by American writer Betty Friedan. According to Friedan, a woman who goes out for work and earns is the one who is empowered, whereas a woman who stays at home is not (Friedan, 2010). This research provides contrary evidence to this conception of women empowerment, especially in the Indian context.

The perception of the concept of women empowerment could be across the globe as there is cultural significance to this conceptuality (Wray, 2004).

Findings suggest that women empowerment is a concept that many older women are not aware of, though the closest word they can relate to women empowerment is ‘Stree shakti’. Empowerment in the context of this sample of women is being able to perform activities that give them pleasure without any restrictions; being a housewife or a working woman does not influence this perception of empowerment.

1.1. Feeling of empowerment

The term empowerment denotes the dynamic transfer of power to someone or something (Mandal, 2013).

Empowerment is a concept that can change based on an individual’s perception. The feeling of being empowered could arise from various experiences, cultural differences, and the association that the woman makes herself (Tsikata & Darkwah, 2014). Most research studies empowerment in the context of women and the possible factors that make them feel empowered.

1.1.1. Treatment of Women

Numerous studies report the mistreatment of women worldwide, from violence against them to lack of access to resources, even during childbirth. This could be attributed to their perceived subordinate position in society, and hence even the professionals involved in women’s care face issues such as low pay at work (Jewkes & Penn-Kekana, 2015). However, there is evidence that women are also treated with dignity and respect and considered goddesses in some parts, such as India. Even some festivals and rituals play a pivotal role in elevating ‘feminine’ to an auspicious state and celebrating phases of womanhood (“Women in the Worship of the Great Goddess”, 2005). The interviews supported this line of positive treatment of women. The verbatim form of the participants’ transcripts report on similar lines, “But in Marathi, it is like they consider women goddesses also and spiritually they are like ‘yeh ghar ki lakshmi hai,’ they take it to another level, they will honor her.” [Verbatim from the transcript]

The verbatims also perceive that the women are the one who manages the finances, the earlier household system where men earned, and the women took care of household duties as well as the finances. The verbatim from the interviews has been reported –

“a system like earlier, wherein the husband used to work and bring home the money, then it would be sensible for the wife to handle the household”

The festivals in India also treat women as being the centre point of the celebration, wherein the participants reported that young girls are the ones always invited for the feast during festivals. The verbatim from the transcript also supports this notion:

“Young girls are given a feast during festivals” [Verbatim from the transcript].

1.1.2. Feeling of women empowerment

The concept of women’s empowerment revolves around equal opportunities and rights in society (Manda, 2013). However, empowerment among women does have a subjective aspect concerning perception.

Some women also experience empowerment by indulging in physical activities (Paulson & Greenleaf, 2022). Women show unique experiences of feeling empowerment even in clinical trials for HIV, where receiving certain forms of therapy has a more positive and empowering effect on them than men (Mantsios et al., 2020).

The interviews also perceived that women empowerment would occur only when there is a suitable platform and direction. The excerpt from the transcript talks about something similar: “People have some misconception like women do not have power but women empowerment in the essence that they should be given a right platform, their talent should have a proper direction then yes.” [Verbatim from the transcript].

The festivals also contribute as these are social gatherings that were important as women used to always be at home. The interviews also have similar excerpts:

” I think these social gatherings at that time we are bringing in quality because a woman was more at home.” [Verbatim from the transcript].

The feeling of empowerment is when a woman can work independently, educate herself, be self-sufficient, voice out their opinions. The verbatims from the transcript represent that:

“She shouldn’t undermine herself, she can independently do a lot of work, so she should remember that, and if there is something unjust happening around her, she should stop it, and she should educate herself, do things for her or her family, she should voice out her opinion”.

The participants also related this to the concept of feminism, representing that feminism is giving a choice, and women empowerment encapsulates flexibility and women being free from restrictions. The verbatim form of the transcript supporting the same is as follows-

“I feel like feminism… There should be a choice even when it comes to marriage and stuff because in urban, we do not see females getting a lot of freedom in marriage or loving someone of their choice.”

“The focus and work on ladies is more because there is something that only women can do, but like making a mala for flowers, aam torans, gents do it, but for functions, festivals, ladies are hampered the most and they get the most exhausted because they have the most work.”

1.1.3. Homemaker as a respectful profession

The job of a homemaker is often devalued and domesticity is looked down upon, ignoring that it is critical in running the household and has immense importance (Matthews, 1987). Betty Freidan shared similar views in her book “The Feminine Mystique”, where she discouraged being a homemaker and emphasized the importance of being a working woman as it is empowering. Though with time, women are embracing domesticity as well. It seems to give them more pleasure than encountering stress at the workplace. Though many women who leave their jobs to stay at home, also keep themselves occupied by starting their small businesses and doing things that matter to them like looking after their children (Matchar, 2013).

The interviews report that women would love to become homemakers as it should also be considered as a profession and it deserves the respect. The excerpts from the interview –

” I would like to be a homemaker. I will be a homemaker only if I will get proper respect, proper things which homemakers mostly don’t get, I would call it a profession.”

Regardless, homemakers are always associated with women taking up that responsibility. Women reported that they feel proud to be a homemaker and getting appreciated for the tasks they perform, makes them feel elated as it was relayed in one of the interviews:

Homemaker is seen as a profession which requires time management and discipline, as they are required to do an immense amount of work in the households. Women in the interviews expressed something similar. “Even if it’s a housewife, she can do it, time management and discipline are two very important things.”

Apart from women working alone, the women also reported the whole house being involved in the process in some or the other way, where if one front is managed by women then the other front is managed by other people in the house. The verbatim extracted from the interview;”Everyone in the household contributes on their part, and I feel that people should do that because if they will not, then there is no joy left.” [Verbatim from the transcript].

- Grihasti (household)

In the vedic ashram system, “grihasthi” is the word used to describe the delegation of tasks and duties during marital life. This stage places more emphasis on social welfare, as compared to personal welfare. Among the four purusharthas, artha (money) and kama (pleasure) are predominantly active in the man’s life (Chakraborty, 2015). Though the role of women in grihasthi is a rather unexplored area in research, as most of them focus on the man. The arthashashtra gives reference to the grihasti model of living and also discusses the clear delegation of tasks and duties among men and women. It empowers both men and women by having laws in place that promote equality by punishing whoever commits any kind of offense against the other, such as dissolution of marriage if the husband does not come back home for a number of days (Kangle, 2010).

2.1. Delegation of duties in household:

Traditionally, housework and childcare have been attributed to a woman, and earning outside the home is related to a man. This division of tasks is not affected even if the woman is also working (Coltrane & Shih, 2010).

Though studies show that for a working woman, the delegation of tasks is more crucial than a man as they have to juggle between family responsibilities, gender norms, and work commitments. Striking the right balance between work and home is a big challenge for them (Rehman & Azam Roomi, 2012).

Studies show that the amount of household work done is proportional to the economic dependence of an individual on the other gender. So, there is a more proportionate distribution of household chores when both men and women are given equal monetary contribution at home (Greenstein, 2000).

The current division of labour system or grihasthi model is becoming more dynamic as women like earlier are not taking care of household duties solely but are also stepping out and earning. This has demanded a shift in gender norms, making household duties more gender-neutral than gender-specific.

2.1.1 Division of duties in household.

As per earlier gender norms and traditions, household chores and earnings were systematically segregated and appointed to a particular gender. Though the young generation is attempting to practice more egalitarian gender norms and work distribution (Sevilla-Sanz, 2009). But this adoption of egalitarian gender norms is still in the process, where a woman, working or not, is still in the center of balancing responsibilities.

The woman is also reported to be the one running the family and taking the most decisions. The verbatim shares similar experiences of women:

“Women will do house chores and he will do outside work.”

“Women only run the family completely in most of the decisions.”

The division of work during the festivals is also important as workload during festivals also increases and hence it becomes important to have some helping hand. Interviews represent that there always is help as in the women of the house are not alone doing all the preparation during the festivals. Rather there is a division of work in the house and not only during festivals but in general as well women perceived that there have not been times when a single person is alone working or taking all the load.

“There has never been a time when one person was bearing all the work.”

The interview verbatim also shares how men are also equally participatory in household works and this notion runs in most of the households.

“In our house, my father used to work in the house, cleaning and all, my father in law used to put on the cooker and clean as well because of our lives in business, and my husband also did the same.”

“Cooking is not a woman’s responsibility only”

“There should not be such a division that this work is of a woman, this work is of gents. Such a division is not needed.

2.2. Expectation from women

Women are expected to perform numerous tasks in their day-to-day lives as it is demanded by their culture, society, and family. For instance, women in some cultures tend to relate the notion of ideal beauty standards with thinness and their ethnic identity, which also leads to the development of eating disorders. (Rogers Wood & Petrie, 2010). Also, though women occupy a predominant part of the workforce now, they are still classified as homemakers and stay-at-home mothers (Hutchings & Michailova, 2014).

This also includes the mistreatments if women have reported going through any.

2.2.1. Societal and family expectations from women

Societal and family expectations affect the identity formation of women. Since women are associated with household chores and childcare according to existing societal expectations, studies suggest that in some cases even though men consider their marriages as egalitarian, many women find inequity in their relationship with respect to work division at home (Askari et al., 2010).

The familial expectations are a reflection of what societal expectations are. The expectations and stereotypes are close in this section which have very different views that the study has obtained from the interviews. The expectations from the women like the woman is the one who should cook, she is one who is taught about how to cook and all the household things as it is assumed that the daughter is the one who is going to continue doing these things.

“I will have to learn this, I should know how to cook and all, so they didn’t like to have a compulsion or anything but it was like, at least learn it, at least for yourself.”

“I feel irritated, because it’s like they try to make you realize like you’re growing up, you are going to get married someday so then you should know cooking ”

2.2.2. Gender Equality

Gender equality refers to both genders being treated as equal, as in many cases men are looked upon as superiors and women as their subordinates. Family is the key point of contact, where one learns about gender roles and equality through day-to-day activities (Helman &Ratele, 2016). Gender equality in a country is frequently associated with its economic development (Breda et al., 2020).

In this study, this domain was explored to understand the experiences of women about gender equality, how they expect the situation to be, or what they think in general about it.

A few women reported that social media, tv-series, and shows spoil the way people look at women, gender roles, relationships between husband and wife, and other such varied experiences.

“TV serial promote gender stereotype.”

They have also reported that now things are changing and that equality is even taking place in the household chores that we do and perform.

“Everyone works, even men know some recipes but if they cannot do something else then they get involved in cleaning.”

2.2.3. Mistreatment of women

Violence and mistreatment of women has been commonly observed. Some instances that lead to this mistreatment of women include dowry demands, interpersonal conflicts at the workplace, and also lack of access to relevant healthcare during childbirth (Natarajan, 2017; Cunningham et al., 2014; Bohren et al., 2015). In the interviews, women have reported instances from other people that they have noticed to experience ill-treatment in the society or households.

“I came across an experience where a parent had put forth a condition on their daughter that she can continue her education but when there is anything that goes wrong, basically if she sets a wrong foot forward then her education will be stopped and she will be asked to get married”

The interviews also inform about instances of domestic violence in the known areas and neighborhood, the excerpt from the interview.

“Sometimes there are instances of domestic violence even from my neighborhood.”

The way women get exhausted because of overload was one of the aspects interviewees reported to be mistreatment with women.

“Ladies are hampered the most and they get the most exhausted because they have the most work.”

This ill-treatment continues to women not getting educated because of several reasons that the parents think, either them being less educated or not at all educated. Participants reported some instances of people in search of brides with less education or no education.

“They were looking for a bride so she was like she should not be that educated”.

- Significance of festivals

Festivals are an integral part of our society, they help establish a sense of community (Derrett, 2003). Festival celebration promotes togetherness and is significant as it ignores the differences among people in society (Fenn & Joshi, 2021).

The interviews also revealed that women expressed that the significance of festivals was looked at to see how significant women thought festivals to be in their lives. Earlier women used to mostly perform household duties not being able to go outside of the house, the justification which women perceived as why festivals were created for women to go out and socialize, exercise, maintain mental well-being, radiate positivity, and others. Festivals were also found significant as earlier a girl used to get married at a very early age which made the festivals a way for her to connect with her family and also play, as the festivals were reported to have association with different games.

3.1. Rationalization of Festivals

Festivals are an integral part of sustaining one’s cultural identity (Zhang et al., 2019). In every culture, there are a few festivals celebrated every year, which are said to have a scientific reason. These festival celebrations can be related to many nature-related factors, such as the floral festival known as “Bathukamma”, celebrated in the Indian state of Telangana, emphasizes the medicinal properties of the flowers used in the festival (Kumar et al., 2018).

As a part of festivals being significant, participants also perceived festivals to have importance and provided a rationalization for the events, rituals, and certain things done. The interviews show that festivals are perceived to elicit positive emotions. They help to socialize, provide pleasure, and also elicit eustress. Festivals are also perceived as facilitating the process of socializing as well. Women rationalized the rituals for scientific purposes.

3.1.1. Rationalization of festival celebration

The festivals are perceived to elicit a variety of emotional experiences such as joy. Also, women tend to experience more of these positive emotions as compared to men during festival celebrations. Interviews revealed that women perceived festivals as a way to bring people together (Lee & Kyle, 2013). “People come together, there is a positive atmosphere at home, it feels good to be with others, your shraddha (devotion) is very active throughout. Because you have to be very positive, all these festivals radiate positivity”.

Festivals were also perceived to provide an opportunity for the working woman to interact with other women around in the neighbourhood, and also with relatives. This also opens opportunities for communication and not only for working women but also for a housewife. “When you meet, there’s so much communication.”

Women also perceived that earlier festivals were a way to express being in a social circle which women during those times did not usually get as they were generally involved in household work itself. “A social circle which then was the only way where a woman could reach out to her friends and establish a social sort of thing.”

Nowadays, there are no such rigid rules of celebrating festivals strictly as the festivals are actually made to experience joy and hence, they are flexible in nature and can be modified as per the need. “Festivals were celebrated for social gatherings, to reduce boredom for women. No such forcing to follow traditions strictly ”

Most women also reported that festivals are not stressful for them; rather they induce eustress, excitement, and joy.

“Do not feel stressed during festivals as I do only what is possible ”

“Usually it is not hectic, some circumstances when the things aren’t started way before the festival approaches it might become hectic.”

“Excitement about the festival, shopping during the time of it, decorations, competitions in the society, visiting other people’s houses to invite them to our house for celebrating the festival. ”

Women also reported that festivals were a way to gain scientific knowledge through festivals such as using medical plants and other such useful things. Women gave the example of the Vat Savitri festival which has a banyan tree involved and women usually meet other women and sit under it to have interaction with other people, the scientific justification which women perceived is banyan tree is one which gives out a lot of oxygen which was important for women as they usually stayed indoors.

“Gain scientific knowledge through festivals (as we use medicinal plants, etc. in festivals).”

Festivals were perceived to provide relief from negative emotions, stress, and anxiety as the house has a whole different energy.

“House is filled with energy and gives relief from anxiety, tension, and worries”

Limitations

This study was conducted during a pandemic which made it difficult to connect to people of some ages (especially older), reach out to certain age groups, and reach out to distant and suburban sections of Maharashtra. The study results could have been more robust by increasing the sample size but due to the unavailability of the sample, this was not possible making it one of the limitations of this study. As the sample is chosen from Maharashtra state, the results produced in the study are limited to the region of the study done. The results cannot be generalized as the study focuses on the experiences of women in Maharashtra and the experiences could differ largely depending on cultural background and the region.

The literature found for the concept of grihasthi and for festivals was sparse and little. Hence, we primarily referred to the primary sources or their apt translations by recognized authors. There is a need for more literature and research on the concept of grihasthi, domesticity, and festivals within the Indian culture and diaspora.

Note of acknowledgment

The last few months of working together amidst a global pandemic have been nothing short of a struggle for everyone. Throughout this tough time, we managed to stay connected through online mediums and work together on this project. We are grateful to IndicA Academy for the immense support, concordance and mentorship received. We thank Mrs. Sumedha Ojha for her kindness, cooperation, and diligence that she offered throughout this journey.

We thank all of the interview participants for devoting their valuable time to us and cooperating with us. We thank Dr. Mira Desai for her wisdom and understanding of the local and global aspects of a grass-roots research project. We thank Mr. Mahendra Chakurdas and Mrs. Suvarna Gund for their patience and cooperation in our online meetings, and the valuable information they provided for the origin of festivals. Lastly, we thank each and every person we have received guidance from.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that festivals are perceived as a medium of bringing people together and facilitating the spread of happiness, feeling of belongingness, and other positive emotions. Women actively participate in these festivals and also experience eustress. Women believe that these celebrations have a scientific basis and benefits for them and their families.

Further, the ascription of empowerment is nowhere limited to a working woman only. Homemakers experience a sense of pride as they relish the responsibility put upon them; they are cognizant that their work is and should be appreciated, especially during festivities.

Homemakers deem housework, family happiness, and building a good culture as a responsibility of the husband and the wife. However, it was observed that the division of labor in the household is not justly balanced, adding a burden on the women of the house, regardless of their status as a homemaker or unmarried. Participants’ inferences show that imbalanced division of work and ascribed gender roles are changing with time; men are also actively taking part in household activities, especially when the woman is working. This marks the shift of the traditional grihasthi structure followed in society, which was a balanced system of work delegation in earlier times.As women are increasingly entering the workforce, this model of grihasthi is accommodating to today’s world, where work delegation is more collaborative than gender-specific.

Furthermore, women experience empowerment or ‘shakti’ through various subjective experiences, though the commonality among all experiences is the presence of autonomy. Finally, the findings of this paper indicate that the application of Friedan’s (2010) conceptualization of feminism and women empowerment to the Indian context is not possible and cannot be justified. Understanding these concepts in the sample studied is not restricted to being a working professional but extends beyond that. Both homemakers, young adults, and working women across generations emphasize the importance of ‘having a choice’ in the context of empowerment. Women empowerment in India has to be a personalized definition, ascribing to the attributes of a woman’s life experiences.

References

Askari, S. F., Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., Staebell, S. E., & Axelson, S. J. (2010). Men Want

Equality, But Women Don’t Expect It: Young Adults’ Expectations for Participation in Household and Child Care Chores. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(2), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01565.x

Bayeh, E. (2016). The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the

sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pacific Science Review B: Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psrb.2016.09.013

Bohren, M. A., Vogel, J. P., Hunter, E. C., Lutsiv, O., Makh, S. K., Souza, J. P., Aguiar, C.,

Saraiva Coneglian, F., Diniz, A. L. A., Tunçalp, Z., Javadi, D., Oladapo, O. T., Khosla, R., Hindin, M. J., &Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2015). The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLOS Medicine, 12(6), e1001847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847

Breda, T., Jouini, E., Napp, C., & Thebault, G. (2020). Gender stereotypes can explain the

gender-equality paradox. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(49), 31063–31069. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008704117

Brunell, L. B., Burkett E. B., (n.d.). Feminism | Definition, History, Types, Waves,

Examples, & Facts

Chakraborty, A. (2015). THEORY OF PURUSARTHAS AND CRISIS OF VALUES

IN OUR SOCIETY. Spectrum: Humanities, Social Sciences and Management, 2, 105–118. https://anthonys.ac.in/resources/documents/facilities/journal/hssm/doc_Journal_HSSM_2015-V2.pdf#page=110

Coltrane S., Shih K.Y. (2010) Gender and the Division of Labor. In: Chrisler J.,

McCreary D. (eds) Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1467-5_17

Cunningham, G. B., Bergman, M. E., & Miner, K. N. (2014). Interpersonal

Mistreatment of Women in the Workplace. Sex Roles, 71(1–2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0398-0

Derrett, R. (2003). Festivals & Regional Destinations: How Festivals Demonstrate a

Sense of Community & Place. Rural Society, 13(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.351.13.1.35

Fenn, L., &dr. Joshi, A. (2021). A Descriptive Study on Cultural Impact On

Celebrating Festivals Of India. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education, 12(13), 1192–1197.

Friedan, B., (2010). The feminine mystique. London: Penguin.

Helman, R., &Ratele, K. (2016). Everyday (in)equality at home: complex constructions of

gender in South African families. Global Health Action, 9(1), 31122. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.31122

Hutchings, K., &Michailova, S. (2014). Research Handbook on Women in International

Management (Research Handbooks in Business and Management series). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Jaeger, K., &Mykletun, R. J. (2013). Festivals, identities, and belonging. Event

Management, 17(3), 213-226.

Jewkes, R., & Penn-Kekana, L. (2015). Mistreatment of Women in Childbirth: Time for

Action on This Important Dimension of Violence against Women. PLOS Medicine, 12(6), e1001849. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001849

K., R., &Kangle, R. P. (2010). KautiliyaArthasastra: Pt. 3. Motilal Banarsidass.

Kumar KS, Ravindra N, Swamy SS.Traditional and medicinal secrets of Bhatukamma:The

floral festival of Telangana.J Pharm Adv Res,2018; 1(5):271-275

Kumar KS, Ravindra N, Swamy SS.Traditional and medicinal secrets of Bhatukamma:The

floral festival of Telangana.J Pharm Adv Res,2018; 1(5):271-275

Kumar, S. P. (1998). Indian Feminism in Vedic Perspective. Journal of Indian Studies, 1.

Kumar, S. P. (1998). Indian Feminism in Vedic Perspective. Journal of Indian Studies, 1.

(n.d.). Empowerment definition.

Lall, R. M. (1933). Among the Hindus: A Study of Hindu Festivals [E-book]. Minerva press.

https://www.indianculture.gov.in/ebooks/among-hindus-study-hindu-festivals

Lee, J. J., & Kyle, G. T. (2013). The Measurement of Emotions Elicited Within Festival

Contexts: A Psychometric Test of a Festival Consumption Emotions (FCE) Scale. Tourism Analysis, 18(6), 635–649. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354213×13824558188541

Mandal, K. (2013). [PDF] Concept and Types of Women Empowerment | Semantic Scholar.

Semantic Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Concept-and-Types-of-Women-Empowerment-Mandal/9f4537a6345e288c93589e61e20b1ce82fd6c49

Mantsios, A., Murray, M., Karver, T. S., Davis, W., Margolis, D., Kumar, P., Swindells, S.,

Bredeek, U. F., Deltoro, M. G., García, R. R., Antela, A., Garris, C., Shaefer, M., Gomis, S. C., Bernáldez, M. P., & Kerrigan, D. (2020). “I feel empowered”: women’s perspectives on and experiences with long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy in the USA and Spain. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 23(8), 1066–1078. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1752397

Matchar, E. (2013). Homeward Bound: Why Women Are Embracing the New Domesticity (0

ed.). Simon & Schuster.

Matthews, G. (1987). “Just a Housewife”: The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America.

Oxford University Press.

Mokta, M. (2014). Empowerment of Women in India: A Critical Analysis. Indian Journal of

sPublic Administration, 60(3), 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019556120140308

Natarajan, M. (2017). Domestic Violence: The Five Big Questions (International Library of

Criminology, Criminal Justice and Penology – Second Series) (1st ed.). Routledge.

Paulson, G., & Greenleaf, C. (2022). “I Feel Empowered and Alive!”: Exploring

Embodiment Among Physically Active Women. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2021-0058

Pandey, K. Tradition, practice and rituals in an indigenous setting: tribal women‟ s festivals.

Women and Children‘s Perspectives, 119.

Rehman, S., & Azam Roomi, M. (2012). Gender and work‐life balance: a phenomenological

study of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211223865

Rogers Wood, N. A., & Petrie, T. A. (2010). Body dissatisfaction, ethnic identity, and

disordered eating among African American women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(2), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018922

Sevilla-Sanz, A. (2009). Household division of labor and cross-country differences in

household formation rates. Journal of Population Economics, 23(1), 225–249.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0254-7

Sharma, A. (2007). Relevance of Ashrama System in Contemporary Indian Society. Available

at SSRN 1003999.

Singh, N. (1992). The Vivaha (Marriage) Samskara as a paradigm for religio-cultural

integration in Hinduism. Journal for the Study of Religion, 31-40.

Tsikata, D., & Darkwah, A. K. (2014). Researching empowerment: On methodological

innovations, pitfalls and challenges. Women’s Studies International Forum, 45, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.03.012

Women in the Worship of the Great Goddess. (2005). Goddesses and Women in the Indic

Religious Tradition, 72–104. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047404231_006

Wray, S. (2004). What Constitutes Agency and Empowerment for Women in Later Life? The

Sociological Review, 52(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.2004.00440.x

Zhang, C. X., Fong, L. H. N., Li, S., & Ly, T. P. (2019). National identity and cultural

festivals in postcolonial destinations. Tourism Management, 73, 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.013

Feature Image Credit : istockphoto.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.