Introduction

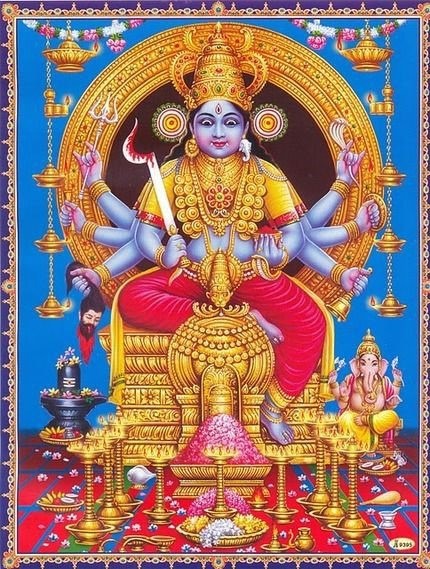

“Bhagavatī” is the name of the great Goddess in Kerala, South India. She is the force underpinning the material world, its śakti. Her power is called forth, enlivened, and worshipped in myriad forms. In fact, the sculpting and awakening of the Goddess in physical form is the fundamental mode of religious practice in Kerala. In her different manifestations, Bhagavatī goes by different names– Devī, Kālī, or Bhadrakāḷī according to context.

We cannot know the historical origins of Bhagavatī with any certainty. In Kerala, the Goddess Bhadrakāḷi refers to the goddess’s violent, bellicose form, as depicted in the foundational Bhadrakāḷī Māhātmyam myth, which can be traced to the Devī Māhātmyam and the Devī Bhāgavata Purāṇa. However, it is the Linga Purāṇa (1.106) that actually mentions the demon Dārika and comes closest to embodying the myth[1]. Later Kerala folklore, the Dārukavadham, tells of her birth directly from the forehead of Śiva to fight the demon Dārika (Dāruka), of her enormous size and ferocity, of her beauty and power, of her bloodthirstiness, and of her military might. While she remains at all times the Supreme Goddess for her devotees, Bhadrakāḷī’s physical form is imagined in different ways through ritual enactments and textual recitation and varies significantly from one community to another. Consequently, different Bhadrakāḷī Sampradayas have developed around the different bhāva-s of Bhadrakāḷī, including raudra, ugra, śānta and mokṣadā. These temporary moods of the goddess are triggered by peculiar events occurring within the framework of her mythological martial acts.

(Figure 1: Credit: Wikipedia – A 17th century daaru-vigraha of Bhadrakāḷī from Kerala)

There are interesting historical and anthropological ramifications for the entire Śākta milieu when we encounter actual vernacular and Sanskrit texts and endeavour to understand them both in their regional context and in the larger context of their trans-regional influences. I will, therefore, review some of the seminal texts along with some of the folk traditions of Bhadrakāḷī Sampradaya of Kerala.

- Textual Sources of Bhadrakāḷī Sampradaya

The earliest extant textual reference to the kula of Bhadrakāḷī can be traced to five tāntrik texts called Brahmayāmala-s[2](Hatley 2007: 3–5). The term tantra, derived etymologically from the root tanu, primarily signifies elaboration or extension: tanyate vistāryate jñānam anena iti tantram. It is thus applied to denote the class of literature which elaborates or extends the frontiers of our knowledge. In the restricted and technical sense, the term tantra refers to the class of literature which deals with religious and mystical content, consisting of mystical incantations (mantra-s) or magical words, which are believed to have the power to bring about extraordinary results. The Kāmikāgama explains its technical meaning thus: tanoti vipulān arthān tattva-mantra samanvitān | trāṇam kurute yasmāt tantramityabhidhiyate: “that which elaborates great things, consisting of truth (tattva) and mystical incantations (mantra) and saves (us from calamities and danger) is called tantra.”The Vārāhi Tantra classifies the vast mass of tantra-s under three divisions, namely Āgama, Yāmala and Tantra.

The Brahmayāmala texts can perhaps be dated to the fifth century or earlier, but solid evidence for them does not become available until centuries later. Alexis Sanderson notes that these texts are already cited in the original Skanda Purāṇa, dating to the early sixth or seventh century (Sanderson 2014: 40)[3]. Of the five Brahmayāmala-s, two are from South India — one is now available at the French Institute of Pondicherry (ms. T. no. 522), while another one is in the Trivandrum Manuscript Library (ms. T. no. 982). The two South Indian manuscripts might have been produced using the North Indian Brahmayāmala-s as their source.

The Brahmayāmala (French Institute of Pondicherry)

The Brahmayāmala manuscript [Brahmayāmala-mātṛ-pratiṣṭhā-tantra], housed at the French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP), consists of some 1,900 śloka-s in 49 chapters. The text is incomplete and is written as a ritual manual (paddhati). Though the author’s name and place of origin are not mentioned in the text, it is generally accepted that it was written in Tamil Nadu or Kerala based on the traces of local language, musical instruments and dance form mentioned therein. For instance, in the context of śūlam pratiṣṭha (the installation of trident), the rituals and musical instruments (karati and timila) referred to in the text[4] are particular to these two regions.

(Figure 2: Credit: Agoda – Velichappadu at Of Edatharikathu Kavu Guruyaoor)

The important contents of this text include the saptamātṛka-pratiṣṭha, daily pūja-s, festivals and significant pūja-s like the kujavarabali and mātṛśānti. Chapter 19 describes the rite of animal sacrifice (paśuyāga) which takes place in saptamātṛka temples. Two community groups, Kurup-s and Velichappad-s, are still practicing this ritual in Kerala to this day.

The Brahmayāmala (Oriental Research Institute, Trivandrum)

The Brahmayāmala manuscript [Brahmayāmala-pratiṣṭha-tanta], available in the Trivandrum Manuscript Library, is another incomplete Southern Brahmayāmala text on the worship of the Mother. The second chapter describes two types of temple idol installation in detail, namely ekabera and bahubera. In the context of ekabera, the icon of Bhadrakāḷī is installed solely for the purpose of blessing monarchs to achieve victory over their enemies. In that of bahubera, the icons of Saptamātṛka-s along with the icon of Bhadrakāḷī are installed for the peace and prosperity of the kingdom. These two installation types have been prevalent in the temples of Kerala for centuries.

Thirunizhalmāla (1200–1300 C.E.)

Apart from the tāntrik texts, we find early literary references to the popularity of Bhadrakāḷī worship in Kerala. An important literary work called Thirunizhalmāla, written between 1200–1300 C.E. — one of the earliest Malayalam literary works[5], provides us with an insight into the ancient ritualistic art tradition of Kerala. It gives a detailed description of the bali ritual worship performed by the Malayar community in the Āranmuḷa temple, which is one of the famous divyadeśam-s (the 108 temples dedicated to Lord Viṣṇu) in Kerala. The ancient rituals recorded are mainly folk rites, particularly for removing various dośa (impurities) of the deities. These rituals were performed by the Malayar community, now settled in North Kerala, where manuscripts of Thirunizhalmāla were discovered. Verse 3.2.5 (written in old Malayalam) in the Thirunizhalmāla provide a description of Bhadrakāḷī.

(Figure 3: Bhadrakāḷī. Thirumudi at a traditional kali temple)

Mātṛsadbhāva (15th Century C.E.)

The Mātṛsadbhāva is a significant text and deserves special attention because it is the only ritual manual dedicated completely to the mātṛ-tantric tradition of Kerala. It is generally believed that this important treatise was composed before the 15th century C.E. (the exact date is unknown). Its author states that at the time of writing this work no existing text provided a complete and organized account of the mātṛ-tantric tradition[6]. Hence, as the author declares, the Mātṛsadbhāva is a comprehensive summary of tantric rituals, which provides an in-depth account of temple worship in the South Indian based on various Yāmala materials. In chapter five, a detailed description of the temple installation procedures for the Divine Mothers, and of Bhadrakāḷī Herself, are given according to the Brahmayāmala[7].

Śeṣasamuccaya (15th Century C.E.)

Besides the Mātṛsadbhāva, its successor the Śeṣasamuccaya, is also considered significant because Bhadrakāḷī in her form as Rurujit was apparently introduced for the first time as a principal deity within its pages. This is not the case in the Mātṛsadbhāva

The Śeṣasamuccaya, written in the late 15th century C.E., prescribes specific rituals dedicated to various deities such as Brahmā, Sarasvatī, Ditya, Śrīkṛṣṇa, Lakṣmī, Kṣetrapāla, Gaurī, Jyeṣṭhā, Kubera, Bhadrakālī, the Mātṛs, Bṛhaspati, Indra and other lords of the quarters. In particular, chapters seven, eight and nine provide a detailed, distinctive explanation of the tantric rituals for worshipping the goddess Rurujit. The principal source used to describe these rituals is the Mātṛsadbhāva, according to Śaṅkara in his commentary on the Śeṣasamuccaya (Śeṣasamuccaya Vimarshini, 7.1).

Apart from these three chapters from the Śeṣasamuccaya and the Mātṛsadbhava, there are several minor texts in Kerala pertaining to the rituals and installation procedures dedicated to the worship of Bhadrakāḷī. A trace of the continuity of the Brahmayāmala tradition can also be seen in these ritual manuals.

- Epigraphical Evidences of the Bhadrakāḷī Cult

Inscription at the Kolārammā Temple (1070/71 C.E.)

An inscription (1070/71 C.E.) has been found in Kolārammā temple of Kōlār (situated in the Nolambavadi of Karnataka), as Sanderson (2007: 277, n. 140) points out, which precisely aligns with the texts of the Southern Brahmayāmala IFP on the details of temple ceremonies and special rituals, etc. It also marks the annual allowances given to a teacher of “Yāmala”, the offerings that should be given to the deities, and the details of various other ceremonies.

Temple Inscription of Saptamātṛka near Guntur (Second Century C.E.)

An inscription on Bheemeshwara temple, newly unearthed by the Archaeological Survey of India in Chebrolu village, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh is an important find which shows that the Bhadrakāḷī Kalpam was already practiced during the second century C.E. This is both the earliest epigraphic evidence for the Saptamātṛka[8] Sampradaya and the oldest Sanskrit inscription yet discovered in South India. Issued in 207 C.E. by the Śātavahana king Vijaya, it records the method of temple construction and idol consecration in Brāhmi scripts. It predates other earlier references of Saptamātṛka worship, such as the early Kadamba and Chalukya copper plates, by nearly 200 years.

- Temples of Bhadrakāḷī Worship

(Figure 4: Credit: Kerala Tourism – Kodungallur Bhagavathy temple)

Something must be said of the ubiquity of Mother temples in Kerala. Even temples dedicated to male deities usually house the Seven Mothers seated in a row represented by small liṅga-s. They are girded by Gaṇapati and Vīrabhadra on either side, and rest in a low-lying base (pīṭha). These Mothers are the Śaktis, the female counterparts, of the main gods. Located outside and to the south of the principal shrine, set in the inner circle of consecrated stones, bali-s are offered to them routinely as worship. Most important among Bhadrakāḷī temples is the ancient Kodungallur Kāvu[9].

Kodungallur Kāvu

(Figure 5: Credit: Facebook – Kodungallur Bhagavathy)

Kodungallur Kāvu is a sacred spot of special note due to its deep mythological connection with many other famous temples of Bhagavatī and other deities in Kerala. Bhadrakāḷī is also propitiated as the deity of small pox and is known as Vasurimala there. Kodungallur Kāvu has long been considered as the centre of the Bhadrakāḷī Sampradaya in the region with a longstanding history, which traces back to 1200–1300 C.E. through Thirunizhalmāla. Among the spiritual centers in Kerala and India revealed by Thirunizhalmāla, Cheekurumpa Kāvu (meaning “Sree Kurumpa Temple”), is a popular Kodungallur Bhagavatī Temple, well known for Bhadrakāḷī worship, in Kodungallur, Thrissur District. Its special mention in this text indicates that Kodungallur Kāvu was widely popular in that period. It is customarily believed that the Goddess at the Kodungallur Bhagavatī Temple has different facets, including Kāḷī, Srikurumba and Kannaki, and devotees have the freedom to worship the forms that they feel the most connected to.

- Bhadrakāḷī in Kerala Folklore

The body of the Goddess Bhadrakāḷī is brought to life with vibrant powder drawings of Her divine form (kalam-s), along with elaborate performances in which costumed performers dance, possessed by the goddess. The celebration also features the enlivening of sculpted images of the goddess, which are permanently enshrined in temples. Meditation, tāntric worship, and the rendering of mythic stories about the Goddess (both oral and written) also take place. There is a great variety in the rendering of these texts in which the Goddess is described in great detail. Some are recited in temples in Sanskrit; others are sung by female farmers to celebrate a successful rice harvest. Each recounts the Dārikavadham (the killing of Dārika). Although this story is exclusive to Kerala, it shares distinct commonalities with some Sanskrit Purāṇa-s and other myths.

(Figure 6: Credit: Kerala Tourism – Bhadrakāḷī Kalamezhuthu at Vikom Mahadeva temple)

Dārikavadham (Dārukavadham)

As Bhadrakāḷī, the Mother Goddess is depicted in her violent warrior form, which we encounter in her founding myth, the Bhadrakāḷī Māhātmyam. Some of its major elements can be traced back to the Devi Mahātmyam and the Devi Bhāgavata Purāṇa. However, it is the Linga Purāṇa (1.106), which actually mentions the demon Dārika, that comes closest to the Kerala version popularly used in ritualistic art forms. Later, the distinctive Kerala version became widely embodied in the Dārikavadham (“The Killing of Dārika”), which tells of the birth, misdeeds and death of demon Dārika at the hands of Bhadrakāḷi. Indigenous to the region, the legend is alive in the oral tradition of Kerala to this day. The basic storyline is as follows:

Demon Dārika, born to one of the two surviving demon women after the annihilation of the entire demon clan by Viṣṇā, wanted to take revenge on the deva-s. After intense and prolonged penance, he finally received a boon from Brahmā, granting him the invincible power to overcome death inflicted upon him by any man, mortal or immortal, and to conquer the whole universe. After receiving this boon, Dārika began to defeat all of the worlds and to rival the deva-s including the king of the gods, Lord Indra. Informed by Sage Nārada about Dārika’s plan to invade Kailāsa (the abode of Lord Śiva), Lord Śiva became enraged. Thus, the terrifying Bhadrakāḷī, with enormous size and ferocity, having numerous heads, arms and legs, emerged from the blazing fire of his third eye. Bhadrakāḷī, a woman who was not born of a human, is charged with slaying Dārika. After gathering her mighty army of bloodthirsty ghosts and spirits in the forest, Bhadrakāḷī slayed Dārika in a fierce battle and thus liberated the universe from evil. Full of wrath and excitement, she came home to Kailāsa still holding the bloody head of Dārika. Her father, Śiva, attempted to pacify her anger by dancing naked in front of her as a form of worship. Finally she returned to calmness and henceforth began to receive offerings from devotees and to protect them.

(Figure 7: Credit: Wikipedia – Kaliyootu At Vellayani Bhagavathy Kshetram)

In the history of Kerala worship traditions, different forms of Bhadrakāḷī worship have developed around the mythological framework of Dārikavadham, infused with local adaptations and variations to suit the communal needs. Many ritualistic folk art forms related to Bhadrakāḷī share the same theme and depict the mythological story of Bhadrakāḷī, visualized in the form of Dārukajit, slaying the demon Dārika in fierce battle. Other art forms, describe the post-war episodes that aim to propitiate and pacify the raging Bhadrakāḷī. For example, the full story of the legend is theatrically enacted in a special ritualistic art form called Mudiyettu. There are several other special ritualistic art forms which employ some parts of the story, viz. Mudiyeduppu, Kali Darikan, Mudippechu, Bhadrakalitheeyattu, Kaliyoottu, Uthirakkolom, Darikavadham and Ninabali, etc. In some other art forms like Padayani, Theyyam, Thukkam, Bhadrakalikkalam, Kuthiyottam, Vadayarvela, Kummatti, Kāchayerum and Andiyattavum, some connections to the legend are seen, but the storyline is not fully depicted. In general, songs associated with the legend are sung during these ritualistic performances. Some major forms of worship are illustrated below:

Theyyam

Theyyam is a popular folk ritual in the North Malabar region of Kerala, which is prevalent in the erstwhile princely state of Kolathunadu (consisting of Kasargod, Kannur, Mananthavady taluk of Wayanad, and Vadakara and Koyilandi taluks of Kozhikode in present-day Kerala). This mode of worship usually takes place once a year in kāvu or kottam, or in tharavadu (ancestral house), or even in non-specific locations, usually between November and June. The major communities that celebrate Theyyam include Vannan, Velan, Malayan, Anjoottan, Koppalar, Pulayar and Munnoottan, etc.

Local communities consider Theyyam to be God itself and seek blessings while worshipping it. Theyyam seems to have its origin in various kulas, and the deity characters can be drawn from many sources, such as Purana-s, forest deities, animal deities, serpent deity, deities of diseases, folk gods and goddesses, forces of nature, ancestors, heroes and martyrs, etc. Among them, most of the female Theyyams are different forms of Bhadrakāḷī. For instance, Karikkali, who is believed to be born from the third eye of Śiva and possess the power of magic, is a common Theyyam performed by the Vannan, Panan and Kulanadi tribal communities. The Bhadrakāḷī-Dārika story is narrated, accompanied by songs, in Kodumkali Theyyam of Malabar. Kaliyattam is another name for Theyyam, which seems to suggest the prominent position that the Kāḷī Sampradaya occupies in the ritualistic realm of Theyyam.

(Figure 8: Credit: Wikimedia – Bhagavathy Theyyam)

Upon the invocation of the deities, Theyyam is carried out in three phases. The first phase is Thottam, when the myth of each deity being propitiated in the ritual is narrated through songs, accompanied by an orchestra of various percussion instruments like chenda, maddalam, ilathalam and cheenikuzhal, etc. It is followed by Vellattam, which is only performed for a few deities. The third and the most elaborate phase is Theyyam, in which kolakkarans (the chosen inpersonators of particular deities) are adorned with intricate facial writings, elaborate mutis (headgears) and costumes which resemble unique deity characters and reflect the local cultures. Various nomenclatures of facial and body writings are Shamkum vairddalam, Olikannu and Kattarampulli, etc. Mutis are designed specifically for particular Theyyam as well. Light materials like wood branches and arecanut stem are used for big mutis, while metals like silver and brass are used for small mutis. The use of fire in the form of Choottu (torch), Pandtham (torch) and Meleri (heap of fire), etc., is an important element of the rites, and it also helps Theyyam costumes to glitter brilliantly during the well-lit performance.

One striking characteristic of this ritual ceremony is the featuring of the great number of female deities. Another characteristic is its extensive influence. Although it is lower caste member who perform the Theyyam, traditionally the entire villages, regardless of caste and creed, take part in these festivals and rituals.

Padayani

Padayani, which literally means “a row of warriors” (also called Pademi), is a spectacular ritualistic folk dance, which blends music, theatre, satire, face masks and painting. It is performed in Bhadrakāḷi temples of Central Travancore (especially in the districts of Kottayam and Pathanamthitta) with full rigor and dedication. This annual celebration takes place between mid-December and mid-May and involves the active participation of the entire village community. It is believed to have been in vogue prior to the 8th century B.C.E. According to the Bhadrakāḷī-Dārika myth, after annihilating demon Dārika, the Goddess’s anger could not be quenched. The disciples were advised by Lord Śiva to perform music and dance to appease her, lest her anger result in the destruction of the entire world. Padayani is also performed to keep evil spirits away from the community to ensure a good harvest. Traditionally, it could last for over 24 days, but nowadays it sometimes lasts for only a single day.

(Figure 9: Credit: Wikipedia – Padayani)

A major part of Padayani performances is the Kolam thullal. Each Kolam (character) wears a unique mask fashioned on leaves of the arecanut palm brought to life with drawn images sketched with vivid-colored powders made of natural materials. Crowned with marvelously decorated headgears, different kolams perform the exemplary, rhythmic movements in devotion accompanied by the percussion instrument called thappu, as well as thavil, maddalam and kaimani. These kolams are representations of various divine characters which include Ganapathi, Yakshi, Pakshi, Kalan, Marutha, Bhairavi, Kaalari and Gandharvan, etc. Another major attraction of Padayani is the rhythmic songs associated with it. These songs have been passed down through oral rendering from generation to generation. The songs are colorful tunes sung in simple Malayalam.

Kalamezhuthu

As the earliest writing found in Kerala, Kalamezhuthu traces its origin back to the dawn of our civilization. It refers to writings or drawings done on the floor. Still prevalent throughout Kerala, it is widely practiced today. As a part of rituals performed either in a temple compound or in a pandal (temporarily constructed ritual area), the first stage, Kalamzhuthu, is usually followed by two other stages – Kalampattu (singing of a myth accompanied by musical instruments) and Kolam Thullal (performance of the myth). The Kerala communities create a unique color synthesis from powders made of natural materials in their surroundings – white from rice powder, black from burned corn husk, yellow from turmeric powder, green from fried leaves of certain vegetables and red from a mixture of turmeric and lime. These elaborate drawings are done with bare hands, without the aid of any tools. The highly skilled artist spreads the powder on the floor between the thumb and the index finger– making it an extremely difficult art to master. The deity chosen, the writing size and style of the image vary from place to place in Kerala. The communities where this folk art dominates include Theymbadi Nambiar, Theeyattu Unni and Theeyati Nambiar, etc.

(Figure 10: Credit: Musemanyou – Bhadrakali Kalamezhuthual)

Bhadrakāḷī kalam is a specific Kalamezhuthu with elaborated rituals performed in Bhadrakāḷī shrines. It is usually conducted during mandala kalam (between the months of December and January). Bhadrakāḷī is drawn in her ferocious bhava and in various sizes depending on the number of her hands, which can vary from 16 to 64. During the writing ritual, Kalamzhuthu songs, detailing the steps of preparing the pandal and narrating the Bhadrakāḷī-Dārika legend, are sung accompanied by traditional musical instruments such as chenda, kuzhal, kombu and cymbals.

Mudiyettu

A magnificent ritual dance drama called Mudiyettu is predominantly performed in Central Kerala comprising Ernakulam, Kottayam and Idukki districts. It enacts the legendary tale of killing demon Dārika by Goddess Bhadrakāḷī. It is a highly complex ritual, combining art, music, dance and theatre, performed in kāvu-s and temples dedicated to the Goddess Mother.

(Figure 11: Credit: Prepp – Mudiyettu)

Before the dance drama performance begins, Kalamezhuthu, an elaborated ritualistic drawing of Bhadrakāḷī, is made on the floor on the backdrop of the Sree Yantra (sacred diagram which represents the Divine Mother) with five kinds of natural-colored powders to invoke the spirit of the Goddess. Later, the kalam (drawing) is swept away to make way for the Mudiyettu. “Mutiyettu” means “carrying of the headgear or head dress”. The muti – the terror-inspiring face and headgear of Kāḷī, her hair unkempt and braided of wood – is put on the actor who plays the role of Bhadrakāḷī. The performance depicts the Bhadrakāḷī-Dārika myth in detail.

Traditionally, actors observe strict penance for purification prior to the performance. Heavy makeup, gorgeous attire, face painting—with tall headgear and oversized ornaments– add a touch of supernatural mystique to the performers. A wooden muti, enlivened with a lifelike mask of the Goddess (complemented by a decorative red vest and flowing white cloth), help make it one of the most beloved performances in all of Kerala. In 2010 UNESCO inscribed Mudiyettu as an ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.’

Among other things, Mudiyettu signifies harmony and unity among all of the castes and creeds of the village. Each caste takes part in and makes its specific contribution to the rituals: members of the Marar and Kurup communities, which are temple bound upper communities in Kerala, are actors of the performance; the Paraya community provides bamboo artifacts and leather for drums; the Thandan community gathers ingredients for mask and muti making; the Kaniyan community paints the masks; and the Kurava community keeps the fire torches burning, etc. Mudiyettu connects all communities through active involvement and a sense of belonging.

Thira

Thira is a social ritual popular in the region of Calicut (Kozhikode). It is performed as an annual festival by the communities of Anjoottan, Kalanati, Panan, Munnoottan and Pruvannan, etc. It closely resembles Theyyam of Kolathnadu and Bhoota Kola of Tulu Nadu, but in a less intense form.

The ritual takes place in three phases, namely Vellattam, Vellakettu and Thira. Vellattam represents the early stage of Devatha, expressed through simple costumes. It consists of thottam (narration of devatha’s story through verses), dance, music, kalaripayattu with sword and shield, simple dance movements, and an interaction with the devotees present. In the second phase, a piece of new cloth is carried on the head of the Vellakettu, while rituals and performances are conducted. In the final phase of Devatha, each Thira, appearing with elaborated facial writing, wearing a huge headgear, and dressed in full costumes (according to the nature and temperament of the character depicted) performs music, dances and interacts with the audience. Rakhtesvary, Bhagavathy, Rakhtachamundi, etc. are Thiras related to Bhadrakāḷī. Some other common types of Thira are Naga Bhagavathy, Gulikan, Kuttichattan, Vasuri Mala, Vettakoru Makan and Pottan.

Bhadrakāḷi Theeyathu

Bhadrakāḷi Theeyathu, which is believed to have existed for more than 1,500 years, dominates in Ernakulam, Kottayam, Alappuzha and Pathanamthitta districts of South-central Kerala. According to history, Theyyattu originated in the Thrikariyoor Śiva temple, which was then under the care of the Chithira Sampradaya of the Namboodiri community. It is usually conducted in Bhadrakāḷī shrines, but is sometimes conducted in the ancestral homes of Hindu families.

(Figure 12: Credit: Devianart – Bhadrakalitheeyathu)

An elaborate ritual performance, it depicts the war between Bhadrakāḷī and Dārika. Popular legends say that, after the fierce fight with Dārika, Bhadrakāḷī returns to Kailasa. Her narration of the whole incident to him forms the basis of the lyrics of Theeyathu songs. Kottu, pattu, kalam-varyal and acting are parts of the ritual. The ritual commences with decorating the pandal by using coconut leaves and various kinds of flowers. Then singing of songs dedicated to Lord Ganapathi takes place followed by songs dedicated to various forms of Bhadrakāḷī, called Uccha Theetyatu. These are performed during the initial phase at mid-day. Then various pūja-s are performed in the pandal. Drumming of rhythm instruments takes place in the evening. At night Thiriyuzhichal, the most integral part of this ritual, takes place before a Nikavilakku, which has a headgear decorated with the idol of Bhagavatī. It features a performance by Bhadrakāḷī dressed in rich costume with facial painting. In addition, kalams (floor drawings), depicting various representations of Bhadrakāḷī, comprise a special feature of this ritual.

Ritualistic Folk Art Forms and Regions

Other popular ritualistic folk-art forms related to the Bhadrakāḷī kula in Kerala include Kaliyoot, Kethrattam, Kolam Thullal, Kolamvettu, Kuthiyottam, Ninabali, Pana, Poothanum Thirayum, Thidambu Nritham and Paranettu, etc. Over the centuries, these living traditions have been extensively practiced, most pervasively in three regions of Kerala– Travancore, Kochi and Malabar. Padayani, Kaliyootu, Paraneru, Thookam and Kuthiyottam are widespread in Travancore, Kannur and Kozhikode; Thiyyattu, Mudiyettu, Pana and Poothanum Thirayum are prevalent in the erstwhile Kochi area; while Theyyam, Thira, Ninabali and Kannyarkkali are popular in Malabar region. Along with classical themes, regional variations of local practice create striking similarity and divergence within the Bhadrakāḷī kula throughout Kerala. In fact, it is extremely rare not to see at least one Bhagavatī kāvu or temple situated in a typical village in Kerala.

Conclusion

The main premise of this paper is to give an overview of the Bhadrakāḷī worship tradition in Kerala by tapping into the currently available literary, archeological and ritualistic folk sources. Myriad forms of this Goddess are worshipped in an iconic form as well as anthromorphic representations throughout Kerala. The presence of thousands of Bhadrakāḷī temples in Kerala certainly suggests an ancient culture that honored the power, beauty and immanent divinity of the Goddess. Unfortunately, the controversy over the history of the evolution of Bhadrakāḷī worship remains a heated dispute within scholarly circles today. With textual and epigraphical sources, we have established that the Kalpam of Bhadrakāḷī was already firmly rooted in Kerala towards the beginning of the Common Era. These sources may well have been codified and disseminated orally for at least two centuries before they were committed to written Sanskrit. While admittedly fragmentary in nature, the textual and folk evidence provides a beginning for contextualizing the Bhadrakāḷī Sampradaya in the history of Kerala religions. The Bhadrakāḷī kula of Kerala is an influential form of Śākta tantric goddess worship, which is just beginning to garner the attention of scholars – the topic is certainly a vast one, and requires further research.

REFERENCES

- Caldwell, Sarah L. (2012). “Whose goddess? Kāḷi as cultural champion in Kerala,” Aryan and non-Aryan in South Asia: evidence, interpretation, and ideology; proceedings of the International Seminar on Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 25-27 October 1996. 85-106.Edited byJohannes Bronkhorst & Madhav M. Deshpande. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors.

- Hatley, Shaman. (2007). “The Brahmayāmalatantra and Early Śaiva Cult of Yoginīs.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania. (Unpublished)

- Koyyal, Balakrishnan. (2016). Folk Art Forms of Kerala. Kerala: Kerala Folklore Academy, Govt. of Kerala.

- Kumar, R. Krishna. (2019). “Earliest epigraphic evidence for Saptamatrikas discovered.” Retrieved from, The Hindu. December 25, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/karnataka/earliest-epigraphic-evidence-for-saptamatrikas-discovered/article30397562.ece (accessed January 2, 2020).

- Pillai, Ajith. K. (2017). “Rituals of Kalicult in Kerala,” The Researchers’ International Journal of Research Volume III, Issue-I (June 2017): 41–50.

- Purushothaman Nair, M. M. (2016). Thirunizhalmāla. Kottayam: Sahithya Pravarthaka Cooperative Society Ltd.

- Sanderson, Alexis. (2007). “Atharvavedins in Tantric Territory: the Aṅgirasakalpa Texts of the Oriya Paippalādins and their Connection with the Trika and the Kālīkula,” Arlo Griffiths and Annette Schmiedchen (eds.)The Atharvaveda and its Paippalāda Śākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition (2007): 195–311.

- Sanderson, Alexis. (2014). “The Śaiva Literature,” Journal of Indological Studies (Kyoto) 24 & 25 (2012–2013 [2014]): 1–113

- Sarma, S.A.S. “Mātṛtantra Texts of South India with Special Reference to the Worship of Rurujit in Kerala and to Three Different Communities Associated with this Worship.” Paper, Ecole franīaise d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), Pondicherry. (Unpublished)

- Sharma, D. B. Sen. (1985). Studies in Tantra Yoga. Karnal: Natraj Publishing House.

[1] See CALDWELL 2012: 92.

[2] See HATLEY 2007: 3–5: “(…) A South Indian text connected with the cult of Bhadrakāḷī, in which some traces of the older BraYā are discernable; another South Indian “Brahmayāmala” related to this of which only a few chapters survive; a short text preserved in a Bengali manuscript expounding a series of ritual diagrams (cakras or yantras), with no discernable relation of the older BraYā; a text of the cult of Tārā by this name transmitted in an untraced Bengali manuscript, a section which has been published; and a “Brahmayāmala” preserved in a single, fragmentary Nepalese MS, which though eclectic, draws directly from the older BraYā.”

[3]For further discussion on the dating of the Brahmayāmala-s, see Hatley 2017: 211-228, and Sanderson 2009: 51-52.

[4] svastivācakavākyañ ca brahmaghoṣan tathaiva ca | paṭahaṃ maddalaṃ tālaṃ karaṭītimilā tathā |

śaṃkhakāhalasaṃyuktaṃ mātṛghoṣan tathaiva ca | (śaṃkhakāhalasaṃyuktaṃ] conj; śaṃkhakālasamāyuktaṃ Ms.) (Brahmayāmala IFP, p.159)

[5] Its manuscript was published in 1981 named as “Thirunizhalmāla” with commentary by M. M. Purushothaman Nair, Sandhya Books, Calicut. Later it was republished in 2016 by Sahithya Pravarthaka Cooperative Society Ltd. Kottayam, Kerala State, India.

[6]naikatra teṣu samproktāḥ kriyās tantreṣu śambhunā | mātṛyāgaṃ samuddiśya na jānīmo ’tra kāraṇam | tasmād†āpajya tāḥ kartuṃ kriyā lokeṣu naiṣṭikāḥ† | anukrameṇa vakṣyante saṃgraheṇa yathāvidhi | (Śiva did not teach [all] the rituals for the worship of the Mothers in those Tantras in one [place]. The reason for this I do not know. Therefore †…† I shall teach them in summary form in their proper order) (Mātṛsadbhava, p.1–2)

[7]athaikavīrīṃ pratimāṃ pravakṣyāmi samāsataḥ | brahmayāmalatantreṣu yathoktaṃ parameṣṭhinā | (Now, [I] will succinctly describe the ekavīrī icon as taught by the Supreme Lord in the Brahmayāmala.) (Mātṛsadbhava, p.26)

[8] bhadrakāḷī tu cāmuṇḍī sadā vijayavardhinī | śatrunāśe śivodbhūtā kaliyuge prakīrtitā |(Brahmayāmala IFP, 1.17) It is explained that Cāmuṇḍā (one of Saptamātṛkas,among Brāhmi,Vaiṣṇavi, Māheśvari, Kaumāri, Indrāṇi and Vārāhi) and Bhadrakāḷī are one and the same.

[9] The word “kāvu” is traditionally used in Kerala which refers to a sacred grove, a patch of nature’s land, usually with simple shrines erected in the open clearing and attached with water bodies such as ponds and lakes.

Feature Image Credit : istockphoto.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.