“In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unknown, and in between them, there are doors.”(Manzarek, 1967).

INTRODUCTION

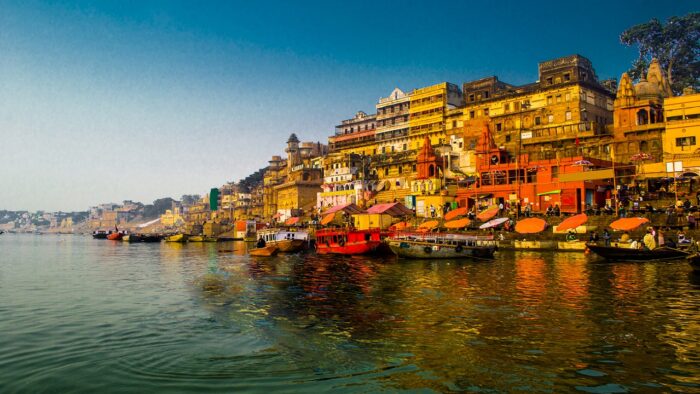

Originating in the Himalayas, the mighty river Ganga flows down to the Bay of Bengal, and it is in its way through the plains of North India that lies the famed city of Varanasi, or Banaras as it is called in the local parlance. Varanasi holds the distinction of being one of the oldest living cities of the world, and a trip to this city can present an almost surreal experience where one can see antiquity rubbing shoulders with modernity. Occupying a central place in the collective mindset of Sanatana Dharma adherents, Varanasi is also revered by the followers of Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism due to the connection of this city with their own religious ideas and historical figures of their respective religions. Considered the spiritual capital of India, a city that promises salvation, Varanasi is renowned as a seat of learning for philosophy, spirituality, religious instruction, mysticism, Sanskrit, Yoga, Samkhya and Tantra and other branches of traditional Hindu education.

From historical times, Varanasi has attracted and intrigued people in equal measure and continues to do so even today. It has played host to streams of visitors and tourists, people in search of salvation, and some searching for meaning of life and still many others coming here for ritual cleansing. Ascetics and Aghoris in equal measure are drawn to this City of Light (Kaashi) and equally importantly, the tourists from all over the country as well as abroad. Religious rites of passage are also conducted at the river front for Hindus.

At the same time, Varanasi has also attracted poets, writers, and philosophers as well as artists and musicians. It has been a centre for learning and also the nodal point for the performing arts. Varanasi has been the cultural and economic capital of Poorvanchal (Eastern part of India comprising of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar).

The prosperous city has found mention in the historic texts of earlier eras, and has been a commercial capital right from earlier times to the modern times, and during the British rule. Traders have settled in here from different parts of the country for trade in the fabulous silks, wooden crafts and the brass work among many other traditional crafts of Varanasi.

In the midst of this influx of travelers and visitors, live the local population of the city who continue with their daily lives, surrounded by so many onlookers and gawkers, eating, praying washing, cooking and also carrying out commercial activities necessary for survival in a material world. They go on with their daily routines, and it can be safely said that in this city of Lord Shiva, dying is a business, but so is living. Both go hand in hand and nowhere is this more evident than at the famous Ghaats of Varanasi, those steps at the riverfront that descend to the Ganga.

These Ghaats are an inalienable part of the experience that is Varanasi. No visitor to the city can ever wash out the image of the Ghaats: For Varanasi, its identity is the Ghaats) and these Ghaats constitute an in-between space, the liminal quality of which distinguishes the river and the buildings dotting its edge: The built form on one side, the Ghaats in between, and the river on the other side.

In Hindu religious thought, sacred spots are imbued with a special quality (of being Fords, to cross over) and the word used for these sacred spots is Teertha. As per belief, a visit to these special places, and Darshan (or glimpse) affords spiritual merit and washing away of sins and leads to salvation or Moksha. Most Teerthas have been built on the edges of water bodies, rivers mostly, and in the absence of rivers, tanks, lakes etc. have also been the site for such Teerthas.

Through this paper, the authors have attempted to understand the unique relationship that exists between the in-between spaces that act as liminal spaces or thresholds between the built form on the river bank and the actual river itself.

The Ghaats of Varanasi cannot be easily defined. They are enticing as well as frightening, at once sensual and repulsive, irrational, and yet spiritually enlightening, and for those who are not looking for any deeper meaning, these Ghaats are just urban space, to be used and consumed, (King, 2001). At the heart of this ambiguity lies the particular charm of the riverfront spaces and combined with the religious and secular aspects of life along the Ghaats, this liminality between the cultural and spatial, and the absence of this liminality at the same time, is what constitutes the living heritage of this place, and can be seen and appreciated4. Each person gets to see, experience, and feel his own adaptation of and understanding of the space, and draws and feeds off what they are seeking.

METHODOLOGY

The paper has been a result of background research as well as personal visits to look at the various aspects of the city of Varanasi, and the iconic Ghaats of the riverfront. The authors have also conducted interviews, informal discussions with locals and visitors, and included their own perceptions of the spaces based on their visits over time. Secondary research includes studying research papers, articles as well as books and online resources on Varanasi, its urban fabric, the religious life and also trying to understand what Liminality means in the architectural sense. The paper has been structured to include the findings in a specific order: Sacred aspects, the mundane aspects, and the in-between spaces.

The Sacred Aspects

“Enlightenment, and the Death that comes before it, is the primary business of Varanasi” (Tahir Shah, 2017).

As per Hindu beliefs, one who dies in Varanasi would attain salvation and freedom from the cycle of birth and re-birth. Considered the abode of Lord Shiva, Varanasi has existed from time immemorial. Varanasi (or Kashi as it is known in ancient Hindu texts) is older than traditions and presents a unique combination of physical, metaphysical, and supernatural elements.

The Ghaats

In most riverside towns and settlements of Northern India, the built part of the city always is at a higher ground. This is done to keep the city safe from seasonal flooding. But in Varanasi, the curiously high perched Ghaats attest to a geographical peculiarity. The bend in the topography of Varanasi has necessitated steep stairway to descend to the Ghaats. These are evident from a walk along the riverfront. Stretching across a 4 km long riverbank, are the bathing steps, totaling 84 in number, these Ghaats are manmade structure that have evolved through the ages, and have continued to change and adapt to the needs of the users of these spaces.

The Ghaat is a real, physical place that can be traversed and observed, but can also be considered a poetic concept, superimposing the imagined over the actual, and for the visitor, the result is an immersive experience, an experience that can be visceral yet holistic, full of impressions that affect all the five senses.

Kashi, the eternal city, as Varanasi is also known as is considered as a place where time stands still, but the city has been destroyed and rebuilt several times over the course of history and most of its buildings are not older than seventeenth century. The built parts of the city do not lodge the history of the city. The real past of Banaras is a past of the mind, upon which nobody sets any store other than in its capacity to inspire the present (Singh, 1987).

The Ganga Ghaats of Varanasi are perhaps the holiest spots of Varanasi and bring the mundane world in contact with the Divine. The River Ganga (Ganges) in Varanasi is believed to have the power to wash away the sins of mortals and the Ghaats are visited by thousands of pilgrims every day to take a dip in the holy river, and to perform rituals and ceremonies.

Dashashwamedh Ghaat is one of the most important Ghaats of Varanasi. The name is derived from the Sanskrit language complex word meaning the site of ten (Dash) sacrificial (Medh) horses (Ashva). According to legends about the Holy Trinity of Hinduism, Lord Brahma (The Creator) sacrificed ten horses to allow Lord Shiva (The Destroyer) to return from his banishment.

This Ghaat provides a beautiful yet chaotic and colorful view. A large number of Sadhus can be seen performing religious rites on this Ghaat. Devotees gather here to perform sacred rites of passage ranging from birth, coming-of-age rituals like the head tonsuring, and funerary rites for the departed. This Ghaat also plays host to the most spectacular Ganga Aarti that takes place in the evening when thousands of earthen lamps are lit and floated in the river by the devotees, and these floating lamps give an ethereal and divine glow to the river in the gathering darkness after dusk.

Just like the glimpses of daily life that one encounters at these Ghaats, we see death too and nowhere is the business of dying more manifest than at the two main Cremation Ghaats of Varanasi: Manikarnika Ghaat and Harishchandra Ghaat.

Manikarnika Ghaat, one of the oldest and most sacred Ghaats, is the main cremation Ghaat of Varanasi. According to Hindu mythology, being cremated here provides an instant gateway to liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth. At Manikarnika Ghaat, the mortal remains of a human are consigned to flames with the prayers that the souls rest in eternal peace. At this Ghaat is a sacred well called the Manikarnika Kund, believed to have been dug by Lord Vishnu (The Creator) at the time of Creation. Thus, the concepts of Creation and Destruction exist side by side here.

The Harishchandra Ghaat is named after a legendary King Harishchandra, who once worked at the cremation ground here, lighting funeral pyres, as a fulfillment of a promise that he had made to uphold truth and charity. His son died and his wife brought the body to this Ghaat for cremation, and unaware about this, Harishchandra arranged the funeral pyre and saw only then that it was his own son. Overcome with great grief, he invoked the Gods, and relenting at his piousness and devotion to upholding the truth, the Gods restored his lost throne and brought his son back to life.

Thus, Hindus from distant places bring the dead bodies of their relatives to the Harishchandra Ghaat for cremation. In Hindu mythology it is believed that if a person is cremated at the Harishchandra Ghaat, that person gets Moksha (salvation).

Situated at the confluence of Ganga and Assi rivers, Assi Ghaat is technically the southernmost of the Ghaats of Varanasi. It was supposed to grow out of the spot where the Goddess Durga had thrown her sword after killing two demons called Shumbha and Nishumbha. The place where the sword fell created a river known as Assi. As per the Puranas and other sacred texts of Hinduism, taking a dip at Assi Ghaat can get the devotee the combined merit of visiting all the major holy places of Hinduism in one go. Especial among these holy baths, are the months of Chaitya (March/Feb) and Maagh (Jan-Feb) and other occasions like solar and lunar eclipses, Ganga Dusshehra, Prabodhini Ekadashis, Makar Sankranti etc.

The Assi Ghaat is also the site for many cultural performances throughout the year, and also hosts a daily programme at dawn called the Subah-e-Banaras that features Vedic chanting, Vedic Yagya (fire ritual ceremony), classical musical performances and Yoga sessions. The Ghaat is also a starting point for boat rides, and a modern cruise boats have recently started plying between Assi and the northernmost Ghaats. Apart from the oar-driven boats, motorized flat-bottomed launches (called Bajraas) also operate from here.

Tulsi Ghaat is another important Ghaat of Varanasi. Named after the great Hindu poet of the 16th century, Tulsidas, Tulsi Ghaat holds an important place in Hindu history. It is believed that Tulsidas wrote his epic, the Ramacharitmanas here, and once the manuscript fell in the river but continued to float and not sink. This place is also believed to the place when the Ramlila was first staged. A temple to Lord Ram has been built there, and the house where Tulsidas lived till his death, houses his relics and his cenotaph.

Tulsi Ghaat (known as Lolark Ghaat earlier) is also associated with a unique event: the holy bath at Lolark Kund to be blessed with sons and their long life. Those suffering from leprosy believe that a dip in this Kund can cure them of their disease. Tulsi Ghaat is also a center of cultural activities. During Hindu lunar month of Kartika (Oct/Nov), Krishna Lila is staged here with great fanfare and devotion.

FESTIVALS AND FAIRS AT THE GHAATS

Due to its exalted religious and cultural significance, Varanasi plays host to a plethora of festivals and holy observances all through the year. There are important festivals dedicated to a particular deity or the other, nearly every month. Apart from these festivals, Melas (Fairs) are also held at Varanasi. These festivals and fairs are celebrated with traditional fervor.

The ‘Ganga-Aarti’ is an important event held daily in the evening and almost all Ghaats organize their own ceremony. Huge lamps are set ablaze, and the priest holds forth the lamp as the multitude chants the hymns. This spectacle is seen by throngs of pilgrims and tourists on the banks of the river as well as boats that are stationed in the water.

The Uttar Pradesh Tourism Department organizes a 4-day festival called the Ganga Mahotsav to showcase the rich cultural heritage of Varanasi, with/performers coming to perform at the celebrations held at Dashashwamedh Ghaat.

Dev Deepavali is held on the full moon day in the month of Kartik (also known as Kartik Purnima, which is a sacred day for Hindus, Sikhs and Jains), when the Gods are believed to descend to the earth from the heavens. This festival is observed with great fanfare and feasts. In the evening, pilgrims and local people decorate the entire riverbank with tiny earthen lamps (‘Diya’). These lamps are lit as a mark of welcome to the Gods as they descend on earth.

Nag Nathaiya Festival held during the month of Nov-Dec, the Nag Nathaiya festival commemorates the episode from Lord Krishna’s life, where Krishna loses his ball in the river, and while diving in to retrieve his ball, he is confronted by a king cobra. The cobra realizes it is Krishna and withdraws and lifts the little Krishna on his hood, Kalia. The Nag Nathaiya festival of Varanasi is held at the Tulsi Ghaat and is thronged by visitors and devotees.

Ram Leela is a popular enactment of the mythological epic, Ramayana. Ram Leela celebration forms an integral part of the cultural life of the Hindi-speaking belt of North India. It is believed that the great saint Tulsidas started the tradition of Ram Lila, the enactment of the story of Lord Ram. The Ramcharitamanas, written by him, forms the basis of Ram Lila performances till today. The Ramnagar Ram Leela (at Varanasi) is enacted in the most traditional style. This special Ram Leela of Ramnagar lasts for almost one month.

THE MUNDANE ASPECTS

Apart from the religiousness of the Ghaats of Varanasi, one also sees the signs of daily life here. Clothes drying on balustrade railings, and sometimes, even on the steps of the Ghaats. The walls of the Ghaats with the Murals of gods and goddesses, signs advertising tuitions for learning Hindi and Sanskrit, advertisements for internet cafes, pizzerias, cafes and restaurants catering to the western palates.

There are tea-stalls selling tea and snacks, kiosks selling tobacco, cigarettes, and betel leaves. Ambulant hawkers selling more tea and light snacks. And in the midst of these, one can also find sellers hawking religious paraphernalia and trinkets and souvenirs.

One can see boat-builders repairing and building boats, boatmen accosting passersby and visitors, promising rides along and across the river at a good price, fishermen with their catch, or sitting mending their nets, barbers looking for customers, masseurs specializing in traditional massage to help heal the body cramps that the bathers get after a dip in the river.

The courting couples, the wandering mendicants/sadhus, the charlatans and the genuine ascetics, the touts promising a good hotel/restaurant with great views, the surreptitious peddlers of opiates and ganja, the idlers and the wasters, the retired men sitting in on hot discussions on politics, the card-players, the gamblers and dice-players betting on small stakes…

Throw in impressive palaces, temples, dilapidated houses, guest homes, hospices for the dying, crumbling mansions once owned by the rich and the famous of India, monastic houses for mendicants, even an observatory,

Add to this mix, children playing cricket, girls playing with dolls, sacred cows roaming around, and the not-so-sacred dogs sleeping or running around, amid the cacophony of the river ducks and geese, all make for a moving palimpsest of life, both divine and otherwise.

LIMINALITY AND LIMINAL SPACES

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines Liminal as:

1: of, relating to, or situated at a sensory threshold: barely perceptible or capable of eliciting a response

2: of, relating to, or being an intermediate state, phase, or condition: IN-BETWEEN, TRANSITIONAL

The noun limen (derived from the Latin) means a point where a physiological or psychological effect begins to be produced, and liminal is the adjective used to describe things associated with that point, or threshold, as it is also called. (Smith, 2001).

Thus, the liminal space is the “crossing over” space – a space where one is not fully in another space, but in a state of passage, or moving from one place to another. It’s a transition space. (Foucault, 1998).

The Ghaats of Varanasi, as discussed earlier, act as transitional spaces for an interface between the built architecture on the one side, and the actual river on the other. This space is imbued with both tangible and intangible heritage that is ever-present in this area. The mythological events and their association with these Ghaats, the shared histories of these places, are continuing to be honoured and perpetuated in the observance of ritualistic practices at these Ghaats

The numerous shrines are a testimony to that, and so are the various sacred spots within these Ghaats. The various festivals and fairs all evoke these mythical associations and enactment of the same ensures their propagation to the current generations, there is a state of pavement, a continuous movement that ensures that the Ghaats are always in a state of hustle and bustle with nary a dullness or inactive state.

THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE

The attributes of liminality are necessarily ambiguous… Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention and ceremonial (Turner, V. 2011).

In Varanasi, The locals consider the 5 things to be their birthright: Daras (the view), Paras (medicine), majjal (bathing), anupaana (drinking) and Sparsh (touching) of the sacred Ganga, for most of the Banarsis, life without these five is inconceivable. (Venkat, 2015, May 30).

Due to the immense religious importance of Varanasi, and the need for the salvation and ritualistic purpose, the Ghaats of the city have been ringed with architecture for the living along with the dying. Temples, mansions of the rich, palaces, pilgrim hostelries, small shrines, monastic orders, various schools of traditional learning all cropped up over the years when the British rule in the region led to a resurgence of Varanasi and established it as a premier city in the region. Not to be outdone, many powerful Hindu princes and royal families of the Indian sub-continent established temples, palaces for their own stay at the Ghaats as well as other structures as acts of piety. Along with that, traditional Akhaaras and Mutts, for mendicants order and sadhus, pehelwaans, and in some places, even hotels and hostelries have cropped up nowadays, along with that, shops selling food, refreshments, tea stalls etc. are seen. In some areas, gateways and portals actually act as significant markers for some Ghaats.

Taking a ritual bath; offering the hair of a newly shorn child; offering prayers for the departed, immersing ashes of the dead; all of these are an immersive experience literally. Taking a dip means surrounding oneself in the holiness.

From dawn to dusk, the river side is alive. Early morning worshippers with Surya Namaskaars, evening aarti of Ganga Maiyaa, and in between the continuing daily activities, coupled with the religious calendar of Hinduism that ensures some or other religious observance or activity is there to keep things alive at these Ghaats.

The special observances as well as the casual visits of the pilgrims, all keep the liminal spaces alive with activities, keeping everything in a state of motion. The chants, the bhajans, the offerings of flowers, lamps, burning incense all contribute to the heady mix of sensations-olfactory, visual, aural, a cacophony of emotions and experiences but at the heart of which there is an inner peace.

CONCLUSION

The tangible heritage of Varanasi’s history is sometimes manifested in the form of its buildings, especially along the Ghaats. However, behind the tangible lie the unseen and intangible aspects that have deep symbolism and sacred importance for the people who dwell here as well as those who visit this place. In fact, it is the intangible aspects like skills, stories, rituals and cultural practices that form the basic foundation for the actual cultural heritage that is visible. This intangible cultural heritage has also continued to evolve to reflect the influences and interactions of Varanasi’s traditional culture vis-à-vis modern life.

As part of the urban fabric of this ancient city, it is well-nigh impossible to separate the sacred from the mundane and can be seen as parts of a dynamic with many layers, sharing a spatial as well as a temporal narrative. From christenings and hair-shoring rituals of newborns to cremations of the dead, the Ghaats of Ganga are a static yet continuously evolving display of all that passes in a person’s life journey. The people who have used these spaces have constructed their own meanings and responses to the contexts and sub-contexts. The deep cohesions between space and the users, affected by culture and customs and social needs is visible in these Ghaats and which have adapted themselves to newer modern contexts.

Coming down towards the architecture of the built form that dots the Ghats and negotiating one’s path through the midst of transactional spaces, one leaves behind the chaos and noise of the crowded street of Varanasi. Descending through the steps, one sees glimpses of the river, a glimpse that is a visual relief from the oppressive walls. The sudden vision of the open expanse of waters of the Ganga moves the heart, fills it with a sense of having attained an almost liberating and exhilarating state of mind. It is this particular and physical experience that can be compared to the Moksha or salvation that awaits a soul when one visits Varanasi. The comparison between the messy and twisted alleys finally leading to the broad expanse of the river can be likened to the release and liberation from the worldly coils into the infinite, merging with the Supreme Being.

Referencing

- Eck, D. L. (1982). Banaras: City of Light. New York:

- Foucault, M. (1998). Different Spaces. In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology (2nd ed., pp.175–185). London: Allen Lane.

- Khanna, A., & Ratnakar, P. (1988). Banaras: The Sacred City. New Delhi: Lustre Press.

- King, R. (2001). Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and ‘The Mystic East’, London: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Lannoy, R. (1999). Benares Seen from Within. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Manzarek, R. (1967). November 6, Newsweek, Music: This Way to the Egress, Page 101, Column 2, Newsweek, Inc.

- Shah, T. (2017) “Varanasi, Benares, Banaras or Kashi, regardlessits not an easy destination.” Indian Experiences: Discovering India Differently (blog). http://memsahibinindia.com/2017/05/11/snapshots-cremations-in-varanasi/

- Singh, R. (1987). Banaras: Sacred City of India. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Smith, V., Barr, R., & Burke, D. (1976). Alternatives in education: Freedom to choose. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa, Educational Foundation.

- Smith, C. (2001). Looking for Liminality in Architectural Space. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from http://limen.mi2.hr/limen1-2001/catherine_smith.html.

- Turner, V. (2011). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti – Structure. New Jersey:Transaction Publishers.

- Twain, M. (1897). Following the Equator: A Journey around the World. Hartford.

- Venkat, V. (2015, May 30). The Sacred and the profane. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/ganga-the-sacred-and-the-profane/article7259596.ece

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.