Introduction

Dharma, artha, kāma, and mokṣa are four puruṣārthas accepted in all the six āstikadarśanas. Mokṣa is considered as paramapuruṣārtha. All the six āstikadarśanas aim at achieving the paramapuruṣārtha. The definition of mokṣa and the means to achieve mokṣa differ from darśana to darśana. The first Nyāyasūtra of Gotama–Pramāṇa-prameya-saṃśaya-prayojana-dṛṣṭānta-siddānta-avayavā-tarka-nirṇaya-vāda-jalpa-vitanḍā-hetvābhāsa-chhala-jāti-nigrasthānānām tattvajnānānniśreyasādhigamaḥ[1] clarifies the main objective of nyāyadarśana, and the way to achieve the objective. The universe is divided into 16 padārthas in nyāyadarśana. According to the above-mentioned sutra, one can understand that the valid knowledge (pramā) of the 16 padārthas will lead to mokṣa. Further, Vātsyāyana in his bhāṣya to the nyāyasūtras explains the approach to valid knowledge of padārthas–trividhācāsyaśāstrasyapravṛttiḥ, uddeśo, lakṣaṇaṃ, parīkṣāceti (nyāyabhāṣyam 1.1.3)[2]. There are three steps to understanding any object, they are uddeśaḥ, lakṣaṇaṃ, and parīkṣā. The first step is Uddeśa, which is to state the padārtha with its name. Then, lakṣaṇam, knowing the padārtha through its definition or lakṣaṇam. Then, parīkshā, which is examining the validity of the knowledge of padārtha. Hence, the knowledge of definitions of padārthas is essential. Though the definition of each padārtha differs, the technique of defining padārthas is a unique concept extensively dealt with in the school of nyāya. Definitions are two types i.e. swarūpalakṣaṇam and taṭasthalakṣaṇam. The definition which is aimed at describing the definitium and not aimed at differentiating the difinitum from the others is swarūpalakṣaṇam. The definition which is aimed at differentiating the difinitum from the others through the unique qualities of the definitum is taṭasthalakṣṇam. Swarūpalakṣaṇam does not have lakṣnam/definition, but, taṭasthalakṣaṇam has one. In this paper we will explore the details and applicability of taṭasthalakṣaṇam with special reference to Indian jurisprudence.

Fallacies of Definition

1.1. Lakṣaṇam/Definition

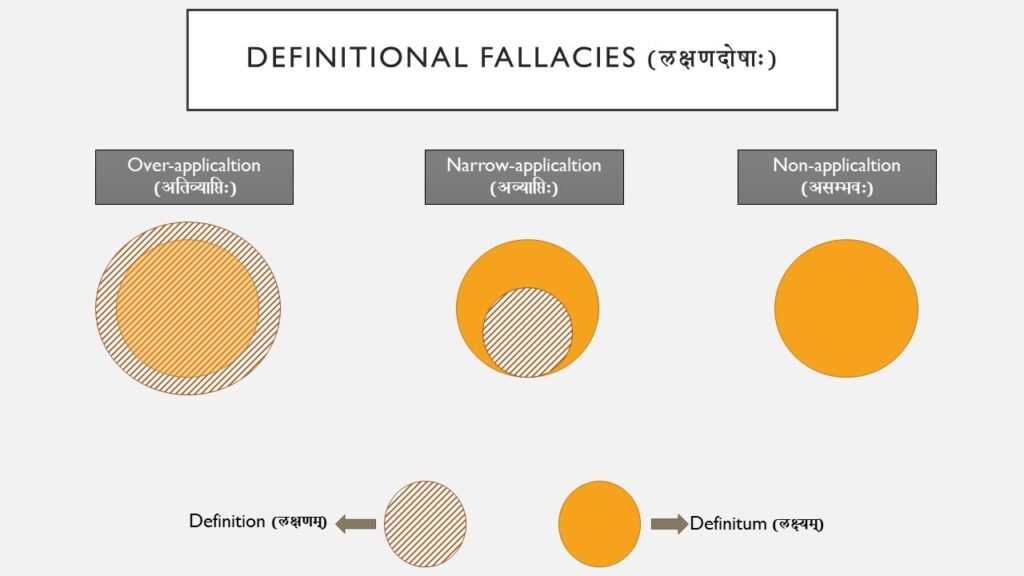

Merriam-webster states, that a statement expressing the essential nature of something[3] is a definition. Etaddūṣṇatrayarahitadharmolakṣaṇaṃ[4] is one universal definition to all definitions found in tarkasangrahadīpikā. This means the unique attribute which does not have the three fallacies qualifies to be a definition of the definitum/lakṣyam. The three fallacies of definitions are ativyāptiḥ, avyāptiḥ, and asambhavaḥ. These fallacies are called over-application, narrow-application, and non-application respectively.

1.2. Ativyāpti/Over-application

Lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-samānādhikaraṇatve sati lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-avachchhinna-pratiyogitāka-bheda-sāmānādhikaraṇyaṃ[5] is the definition of ativyāpti/over-application fallacy. If the (apparent) definition is in congruence with the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka) and the non-definitum-ness (lakṣyabhedaḥ), then the definition is to be believed over-applied or has the fallacy called over-application. For example, if ‘having horns’ is the definition of cows, the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka) i.e. cow-ness is in congruence with the definition. But non-cow animals such as buffalo etc. also have horns. So the definition is in congruence with non-cow-ness also. Hence, the definition – of having horns – has an over-application fallacy.

1.3. Avyāpti/Narrow-application

Lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-samānādhikaraṇatve sati lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-samānādhikaraṇa-atyanta-abhāva-pratiyogitvaṃ[6] is the definition for avyāpti or narrow-application fallacy. If the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka) is in congruence with the (apparent) definition, and the absence of the (apparent) definition is in congruence with the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka), then, the definition is to be believed narrow-applied or has the fallacy called narrow-application. For example, if ‘having black color’ is the definition of cows, the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka), i.e. cow-ness is in congruence with the (apparent) definition via black cows. But non-black cows do not have black color. So, the absence of the definition is in congruence with the delimiter of the definitum-ness. Hence, the definition – having black color – has a narrow-application fallacy.

1.4. Asambhavaḥ/Non-application

Lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-vyāpakībhūta-abhāva-pratiyogitvaṃ[7] is the definition of asambhavaḥ/non-application fallacy. If the absence of (apparent) definition (lakṣaṇābhavaḥ) pervades the delimiter of difinitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedaka), then the definition is to be believed non-applied or has the fallacy of non-application. For example, if having one hoof is the (apparent) definition of a cow, then, whereever there is cow-ness, there is no (having) one hoof, because cows have two hoofs. Horses have one hoof. So, the absence of the (apparent) definition pervades the delimiter of the difinitum-ness. And the definition is the counter positive (pratiyogi) of such absence. Hence the definition – having one hoof – has a non-application fallacy.

(Figure 1: Credit: Srinivas, J. (n.d.) – The three fallacies of definition, illustration)

Lakṣaṇa-lakṣaṇaṃ/Defnition’s definition

Until now we came to know what are the fallacies that should not be in a definition. But, still, we are not clear about the quality that a definition should possess, i.e. the definition of definition. Sa evaasādhāraṇa dharma ityuchyate[8], the attribute which does not have the said three fallacies are called as asādhāraṇa dharma. This asādhāraṇa dharma is lakṣaṇam/definition. Further, the asādhāraṇatvam or uniqueness of the attribute is defined, which is called as lakṣaṇa-lakṣaṇam/definition̍s definition. The aṣadhāraṇatvam is lakṣyata-avachchhedaka-samaniyatatvam[9]. The quality/attribute which is pervaded (vyāpyam) by, and pervades (vyāpakam) the delimiter of the definitum-ness (lakṣyata-avachchhedakam) is qualified to be a definition. Samaniyatatvam means equal invariable concomitance. For example, the perfect definition of a cow is – a living being that is having dewlap (sāsnā).The dewlap is an organ that is unique to cows. Animals other than cows do not have this organ. Hence, where ever there is cow-ness there is the dewlap, and, where ever there is dewlap there is cow-ness. Therefore, the definition of having a dewlap, has equal invariable concomitance with cow-ness, and, it is proved to be a perfect definition of the cow.

Applicability of Lakṣaṇa-lakṣaṇaṃ

1.1. Culpable Homicide and Murder

In the bare act of the Indian Penal Code, the definitions of culpable homicide and murder are dealt with in sections 299 and, 300 respectively. Culpable homicide is defined as –Whoever causes death by doing an act with the intention of causing death, or with the intention of causing such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, or with the knowledge that he is likely by such act to cause death, commits the offense of culpable homicide[10]. Murder is defined as –culpable homicide is murder, if the act by which the death is caused is done with the intention of causing death, or—

2ndly. —If it is done with the intention of causing such bodily injury as the offender knows to be likely to cause the death of the person to whom the harm is caused, or—

3rdly. —If it is done with the intention of causing bodily injury to any person and the bodily injury intended to be inflicted is sufficient in the ordinary course of nature to cause death, or—

4thly. —If the person committing the act knows that it is so imminently dangerous that it must, in all probability, cause death, or such bodily injury as is likely to cause death, and commits such act without any excuse for incurring the risk of causing death or such injury as aforesaid[11].

The summary of the definitions is – an act that leads to death with the intention of causing death. Hence the intended differentiation of culpable homicide and murder is not possible from the wording of the sections. In section 300, it is mentioned that every murder is culpable homicide, which means that culpable homicide is pervaded by murder. If the definition of culpable homicide is the same as murder, then the definition of culpable homicide has the over-application fallacy. The reason for the confusion is the word intention mentioned in both acts. In order to distinguish both the acts, many cases, and judgments are referred to. A lot of effort goes into differentiating both acts. Because the offenses end up in the death of the victim. The conclusion of differentiation is based on one important factor i.e. ‘intention’. Therefore, an act with the ‘intention of causing death’ which shall lead to death is murder. And an act that leads to death, wherein the ‘intention’ cannot be established is called culpable homicide.

1.2. Definition of Fact

In the bare act of The Indian Evidence Act, the definition of ‘Fact’ is – anything, state of things, or relation of things, capable of being perceived by the senses; (2) any mental condition of which any person is conscious[12]. If we examine, the first part ‘anything’ is sufficient as the definition of ‘fact’. The additional phrases describe what a fact is for a better understanding. A lakṣaṇam/definition is expected to be precise, the constituents of the definition should serve the main objective of the definition i.e. differentiating the definitum and the purpose of the constituents should be avoiding any possible definitial fallacies. In the present example, the additional adjectives such as – relation of things, capable of being perceived by the senses, and any mental condition of which any person is conscious, do not serve the purpose of avoiding any fallacies. Hence, we can conclude that the first part –‘anything’ is the taṭastha-laskṣanam of fact. And the rest is svarūpa-lakṣaṇam of fact.

1.3. Common Intention

In the bare act of the Indian Penal Code, the common intention is defined in Section 34 as – When a criminal act is done by several persons in furtherance of the common intention of all, each of such persons is liable for that act in the same manner as if it were done by him alone[13]. The ambit of the section is too wide according to the section’s wording. Any person who intentionally or unintentionally, directly or indirectly indulges in an act of crime committed by a group of people comes under this section. A recent judgment by the Kolkata high court in December 2019, limits the scope of the section. The judgement of Justice Joymalya Bagchi and Justice Suvra Ghosh reads – Common intention under Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code is a species of constructive liability which renders every member of a group who shares such intention responsible for the criminal act committed by anyone of them when such act is done in furtherance of the common intention. Common intention, however, cannot be confused with similar intention. Although accused persons may have similar intention to commit a crime, say murder, until and unless the pre-requisites of: (a) pre-consent, (b) presence and (c) participation in respect of each accused are established, it cannot be said that they shared common intention and be culpable for the crime committed by any of them in furtherance to such intention[14]. Here, the judgement limited the ambit of section by adding the three pre-requisites. This is similar to the adjectives added in a taṭastha-lakṣaṇam to avoid the fallacies.

1.4. Dacoity

In the bare act of the Indian Penal Code, dacoity is defined in section 391 as – When five or more persons conjointly commit or attempt to commit a robbery, or where the whole number of persons conjointly committing or attempting to commit a robbery, and persons present and aiding such commission or attempt, amount to five or more, every person so committing, attempting or aiding, is said to commit “dacoity”[15]. This can be an example of a perfect definition. Dacoity is basically robbery. But it is differentiated from robbery by the adjective – five or more persons indulging in a robbery. So, this adjective helps in avoiding ativyāpti/over-application fallacy in the definition of dacoity.

Conclusion

A study of lakṣaṇa-lakṣaṇa helps the student to understand the definitions more precisely, and even helps in finding the shortcomings of the present acts. The study of lakṣaṇa-lakṣnam would help the student to employ the knowledge of the fallacies etc. on the first sight of any definition or section and enhance their understanding of the subject, and its ambit.

Bibliography

- (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai.

- Gotama, Vātsyāyana, &Sudarshanacharya, S. (n.d.). Nyāya-bhāṣya with prasannapada. Bauddha Bharati, Varanasi.

- Bare Act, Indian Evidence Act 1872

- Bare Act, Indian Penal Code 1860

Website

- https://www.juscorpus.com/the-confusion-between-similar-intention-and-common-intention/

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/3497494/

- https://www.barandbench.com/news/common-intention-under-section-34-ipc-cannot-be-confused-with-similar-intention-calcutta-hc

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

[1]Page no. 04, Gotama, Vātsyāyana, &Sudarshanacharya, S. (n.d.). Nyāya-bhāṣya with prasannapada. Bauddha Bharati, Varanasi.

[2]Page no. 17, Gotama, Vātsyāyana, &Sudarshanacharya, S. (n.d.). Nyāya-bhāṣya with prasannapada. Bauddha Bharati, Varanasi.

[3]Meaning of definition. (n.d.). Https://Www.Merriam-Webster.Com/. Retrieved May 19, 2022, fromhttps://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/definition

[4]Page no. 60, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai.

[5]Page no. 09, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai

[6]Page no. 09, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai

[7]Page no. 09, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai

[8]Page no. 60, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai

[9]Page no. 61, Annambhatta. (1960). Tarkasangrahaḥ with niruktiḥ, nyāyabodhinī, dīpikā, prakāśa, vākyārthabodhinī. VavillaRamaswamiSastrulu and sons, chennai

[10] Bare Act, IPC 1860, C. 16, Sec. 299

[11] Bare Act, IPC 1860, C. 16, Sec. 300

[12] Bare Act, IEA 1872, C. 01, Sec. 03

[13] Bare Act, IPC 1860, C. 02, Sec. 34

[14]JaganGope&Ors vs State Of West Bengal (2019), AP/AS/SDAS & PA Item No.213, retrieved May 23, 2022, from https://indiankanoon.org/doc/3497494/

[15] Bare Act, IPC 1860, C. 17, Sec. 391

Feature Image Credits: istockphoto.com

Conference on Ethics Law & Justice

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.