Continued from Part 1

Baji Rao II, the ex-Peshwa, died in Bithoor on 28 January 1851, surrounded by mourners in the palace and streets of Bithoor. His death placed his adopted son Dhondopant, known as Nana Saheb, at the helm of his estate. Baji Rao had prepared a will ten years before his death, appointing Nana Saheb as “Mukhya Pradhan” and as “master and heir to the gaddi of the Peshwa” after his death.

At the time of his death Baji Rao’s assets included government promissory notes to the extent of sixteen lakhs of rupees at 5 per cent, loan yielding an annual income of eighty thousand rupees besides other assets. There was about one lakh and ten thousand rupees in the treasury for the use of the family. The population of Bithoor exceeded 15,000 at this time, with several people too old to have any prospects of finding employment anywhere. Baji Rao’s pension was stopped with his death, leaving Nana Saheb with a large retinue to support without adequate income. The office of commissioner was folded after Baji Rao’s death. Nana was allowed to keep a retinue of 200 infantry and cavalry, with three guns of small calibre.

The issue of continuity of his pension after his death had worried Baji Rao in his later years. He had sent several petitions in this regard, at one point he even contemplated sending an agent to England, but gave up after 1847. Nana Saheb pursued this matter vigorously now. A petition was sent through Jwala Prasad, one of his officers, to Calcutta. One Fredetick L. Biddle was hired to represent the case with the board of directors.

In 1853 Nana Saheb sent Azimullah alongwith, Mohammad Ali Khan, Piraji Rao Bhosle and Jwala Prasad to London. Piraji Rao died en-route to London. Azimullah had grown up as a servant in a British missionary, where his mother worked as an “Ayah”. He had learned English and French, and was familiar with the British customs. In London, this group was tutored by Satara Raja’s agent in the practices of working with British official machinery and cultivating relationships with influential people. However, the directors rejected the petition and refused to discuss the matter any further. Azimullah returned via Crimea, where he witnessed the ongoing war between Russia and British-Ottoman alliance. Azimullah also brought a printing press with him, which was subsequently used for publishing pamphlets in 1857.

Meanwhile, Nana Saheb had settled into the life of the head of a “princely state” in Bithoor. Baji Rao had built a large menagerie. Nana Saheb maintained it with great passion – showing his elephants, camels, horses, dogs, pigeons, falcons, wild asses, apes, aviary full of birds and other curiosities to his guests. Under him the Bithoor palace became famous for parties, balls, and banquets. His guests described him as a charming host who “mixed freely with the company, inquired after the health of the Major’s lady, congratulated the Judge on his rumored promotion to the Supreme Court, joked the Assistant Magistrate about his last mishap in the hunting-field, and complimented the belle of the evening on the color she had brought down from the hills of Simla.”

Visitors describe the palace decorated with mirrors, chandeliers, expensive carpets, and paintings by European artists. Furnishings included a large dining table, piano and billiards table. Nana Saheb himself played billiards quite well. He also kept himself well informed, subscribing to many newspapers of that time – including the Delhi Gazette, the Mofussilite, and the Calcutta Englishman. A translator was employed for the sole purpose of reading these journals to him every day. Parties continued in the palace until 1856, before the events took a serious turn.

Intelligence was coming from various places across India about a strange movement involving exchange of Chapati and Lotus flowers across India. Rumors of greased cartridges help ignite an already volatile situation, leading to the revolt of 1857. In Kanpur, fearing action, General Hugh Wheeler sought assistance from Nana from nearby Bithoor, who sent two guns and 300 men to him. The revolt broke on 5th June and Nana was placed at the head of the rebellious army. The soldiers initially wanted to march towards Delhi but were asked to stay in Kanpur by Nana. A siege was placed on Wheeler’s entrenchment where most British families of Kanpur had taken shelter. The British forces eventually surrendered and were given a safe passage to Allahabad. However, most survivors of the siege, including women and children, were killed in massacres of Sati Chaura and Bibighar. A month later, Henry Havelock marched towards Kanpur and defeated Nana’s forces after intense fighting in Fatehpur, Pandu Nadi and Kanpur.

With the fading of the Indian resistance, Nana Saheb came to Bithoor one last time, collecting any portable valuables before departing in a boat in Ganga. Among the items taken with him was a robe given by Ramdas Swami to Chhatrapati Shivaji, the robes of Peshwa and an ancient Shivling. All these valuables were later consigned to Ganga. After bidding farewell to a small gathering of followers, Nana and family boarded a boat. The crowd watched from a distance as the candles went off and the boat disappeared into darkness.

This was the last public sighting of Nana. Some credible accounts placed him in Awadh and Nepal afterwards. Almost a century later a Naulakha necklace belonging to Baji Rao Peshwa appeared in the auction of Raja of Darbhanga.

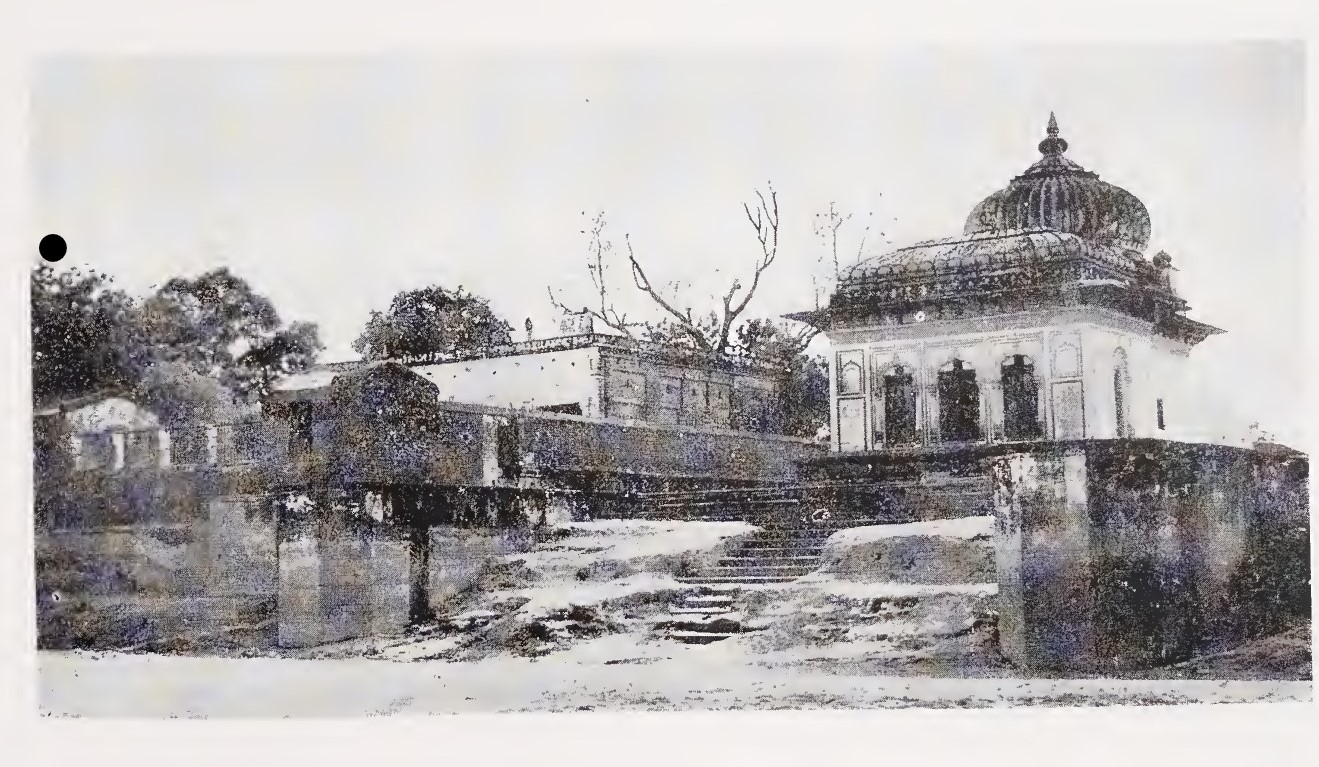

Sarasteshwar, the Samadhi of Saraswati Bai, wife of Baji Rao II, one of the sites of looting

Sarasteshwar, the Samadhi of Saraswati Bai, wife of Baji Rao II, one of the sites of looting

Image Source – 1857: A Pictorial Presentation, Publications Division

After Nana’s departure, the rebel forces tried to defend Bithoor but lost after intense acting which included hand to hand combat. This was followed by loot and massacre by the British forces. The palace was burnt down by Major Stephenson’s troops. The piano and billiards table were seen in the rubble. A monkey from the menagerie was later sent to London zoo. Temples built by Baji Rao were demolished and were stripped of granite. Any man found on the streets of Bithoor were killed.

As this carnage and destruction was taking place in Bithoor, the vestige of the empire which commanded armies from Attock to Cuttack was floating away somewhere in Ganga.

Ruins of the Bithoor Palace

Ruins of the Bithoor Palace

Image Source – 1857: A Pictorial Presentation, Publications Division

Sources:

- Gupta, P.C., The Last Peshwa and the English Commissioners, 1818-1851

- Gupta, P.C., Nana Sahib and the Rising at Cawnpore, 1963

- Kincaid, D., British Social Life in India 1608 – 1937

- Dodd, George, The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China, and Japan: 1856-7-8, With Maps, Plans, and Wood Engravings

- Trevelyan, George Otto, Cawnpore, 1910

- Michael Herbert Fisher, Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain, 1600-1857, 2004

- Sen, S.N., Eighteen Fifty-Seven, 1957

- Francis Jarman, Azimullah Khan—A Reappraisal of One of the Major Figures of the Revolt of 1857, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 31:3, 419-449, DOI: 10.1080/00856400802441912, 2008

- Vishnubhat Godse, Adventures of a Brahmin Priest: My Travels in the 1857 Rebellion – Mazha Pravas, 2014

- https://www.livehistoryindia.com/forgotten-treasures/2017/07/13/lost-jewels-of-darbhanga

This article first appeared here and is being reproduced with the author’s permission.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.