We remember.

It is the defining characteristic of the human species.

We remember.

Civilization began when we developed the means to transfer our act of remembrance beyond the possibilities of genetic or behavioral memories. That became the origin of culture.

We drew on the walls of caves, we wrote on clay tablets and papyrus, we danced to primal rhythms, we sang songs and we composed verses.

We remembered. We told stories. We found heroes and villains. We sought the great cosmic logic that governs our existence.

This fundamental social mechanism of passing down our memories from generation to generation, to derive knowledge and meaning from them, to seek the ability to discern right from wrong, to understand the nature of reality itself as a play between the mundane and the divine – led to the development of the Bharatiya Itihasa-Purana tradition.

The most epochal human event of the twentieth century was the partition of the British Indian Empire into India and Pakistan. Much has been written about its origins, what could have happened, how it could have been averted. Much has also been written about its aftermath, about the death and suffering of millions, about broken families and lost homes. The subsequent years have brought forth the information that has given us a myriad of perspectives on the events that led to the catastrophe.

Today, we live in the information age. Some claim we live in a “post-truth” era, where narrative triumphs over facts. Many decry the fall in journalistic ethics and standards. Was it always so? How was truth presented to the public 70 years ago? How were the events which we consider seminal today perceived by the people of that age?

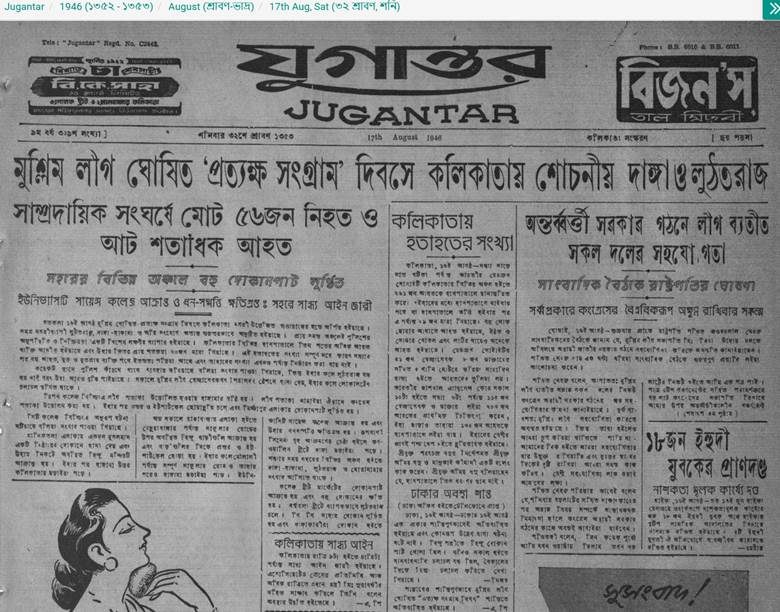

To understand this, I dug into the archives of two venerable Calcutta-based newspapers – the Bengali language Jugantar and the English language Amrita Bazar Patrika. I was looking for five specific dates – 16th to 20th of August, 1946.

I was looking to read about Direct Action Day and its aftermath.

16th August

Jugantar led with the news about the release of political prisoners of Bengal, and about a meeting between Jawaharlal Nehru (curiously referred to as Rashtrapati) and M.A Jinnah. There was no reference to the Muslim League’s plan of Direct Action Day on the front page or the fact that the Bengal government had declared a holiday in support of it.

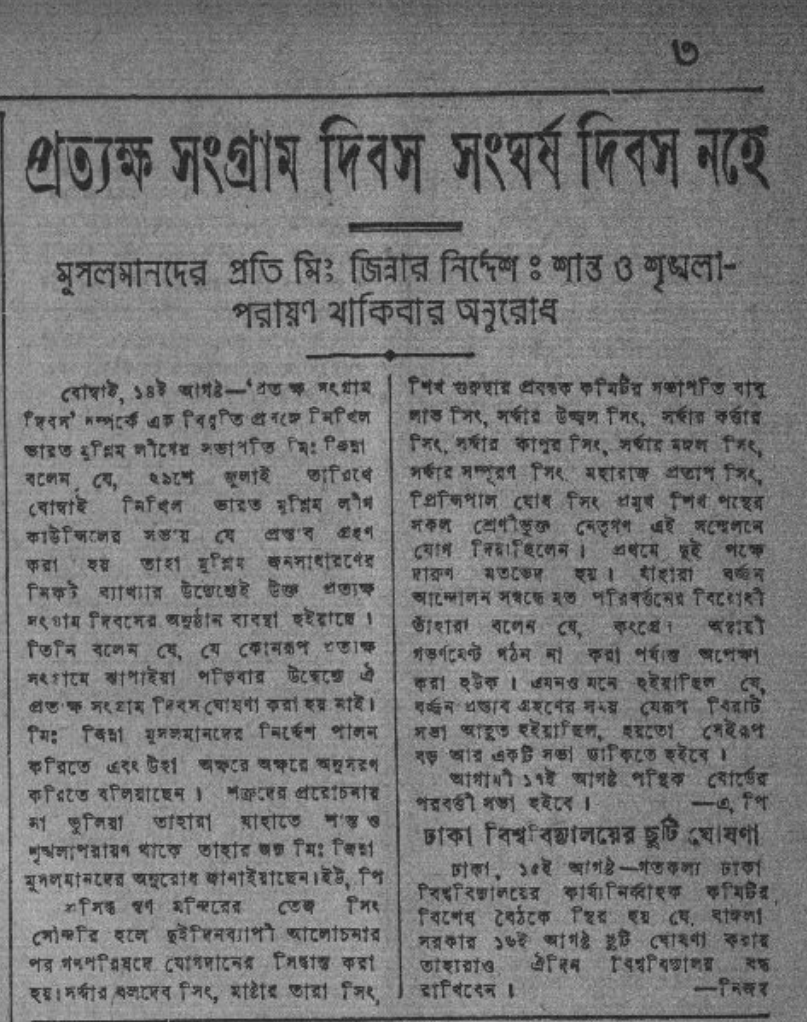

In the third page, we find a piece about Jinnah’s appeal to the Muslims to maintain law and order, with an addendum that Dhaka University had declared a holiday on the 16th.

The Amrita Bazar Patrika, on the other hand, commented upon the “dangerous atmosphere created by the league government”, and added that there will not be any tram services in Kolkata on that day.

On the third page, we find a similar snippet, below a letter lamenting about the scarcity of fish in Kolkata, about the Bengal Muslim League President urging to avoid violence.

The mood of the times that we get from both of these newspapers is that of mild perturbation and anticipation of some law and order challenges. Neither paper had any awareness that they were sitting on a powder keg about to explode.

An explosion that will later be termed as “The Great Calcutta Killings.”

17th August

The picture was different on the 17th. Jugantar led with the headline “Lamentable riots and arson in Kolkata on ‘Direct Action Day’ called by the Muslim League.” There are details about shops being robbed, Hindu houses being attacked by Muslim mobs.

- In the Maniktala area, a Hindu sweet shop was attacked by Muslims, who went on to attack a nearby Temple.

- The violence spread from Rajabajar to Circular road, to University Science College.

- Shops in College Street, Dharmatala areas faced massive losses due to looting.

- The Cinema Hall Rupabani got attacked, following which violence spread in Cornwallis Street.

- The offices of The Statesman newspaper got attacked.

- We find reports of stone, soda bottle pelting, and organized mobs attacking Hindu localities.

- We also find initial reports of Hindu residents fleeing from their areas.

- There are reports of Muslim Students unfurling the Muslim League flag, and then those being pulled down and replaced with tricolor, and that leads to tensions.

- There are reports of both Hindu and Muslim shops being looted at a few places.

There are also claims that the police were completely missing from the action, or totally ineffective when they did arrive. However, we find a report that evening that curfew had been declared, and that Dhaka was majorly peaceful.

Amrita Bazar Patrika led with a far more ominous headline – “Calcutta under mob rule.” It claimed 161 dead and over 800 people were injured.

Curiously, there was no reaction from either Nehru or Gandhiji on what had happened. We find them talking about grand issues of government formation or ruminating on the “ideal state.”

The overall impression that we get is that of a stunning society, unexpectedly coming face to face with a brutal and ugly reality.

18th August

The violence continued unabated the next day too. Jugantar’s headline read “Terrible communal riots on Saturday too in Kolkata: Section 144 declared in the city.”

The paper claimed more than 250 people had died and more than 1600 had been injured till evening. Telephone lines were not working and the transport system had collapsed.

Mr. Kiranshankar Ray, leader of the Congress assembly party, lost his son-in-law in the riots. His house was about to be set on fire until the minister Shamsuddin Ahmed intervened and stopped the mob. The fire brigade had doused 230 fires and was on the verge of being overwhelmed due to a sheer number of incidents.

The paper reports that Sarat Chandra Basu and the Bengal Premier Suhrawardy visited various affected areas and appealed for calm.

Amrita Bazar Patrika rues the “Fratricidal War”, and published and appealed for peace from members of both the Muslim League and Congress. We find that the Governor, Sir Frederick Burrows called in the military to stop the violence, and addressed the residents of the city in a radio message.

Amrita Bazar Patrika rues the “Fratricidal War”, and published and appealed for peace from members of both the Muslim League and Congress. We find that the Governor, Sir Frederick Burrows called in the military to stop the violence, and addressed the residents of the city in a radio message.

Both Jugantar and Amrita Bazar Patrika, on their front pages, printed an appeal from Jinnah to stop the violence. Neither had any words from Nehru, Gandhiji, or Central Congress leadership.

19th August

On the 19th, Jugantar reported that the city was “Comparatively Peaceful” due to patrolling of the streets by both the military and police. However, in several places, the police had to open fire on mobs leading to death and injuries. We also find reports of the carnage from previous days emerging – horrifying riots from all corners of Kolkata. There are reports of combined peace marches by the Muslim League and Congress.

There are reports that Nehru and Lord Wavell had a meeting, but we don’t see any comments from him or Gandhiji on the situation in Kolkata.

The mood is remarkably different in Amrita Bazar Patrika. It reports that the city is “strewn with dead bodies,” and that the disturbances continued “unabated.” It laments “inadequate” military patrolling which leads to the continuation of “murder, firing & arson.” Markets were closed, shops that hadn’t been looted were shuttered, telephone lines were dead and no transport was available. The paper commented that there was no way of knowing the actual figures of the dead and the wounded since the city was littered with corpses.

There is a big statement from Nehru on high-sounding state affairs, but no mention of the happenings in Calcutta.

20th August

On 20th, Jugantar’s headline read that three thousand had died and thirty-three hundred injured over the past three days of the Calcutta Riots. One could sense a semblance of normalcy returning – tram services began in south Calcutta, special arrangements for ration were being made in relief camps, and lorries were put in action to transport government employees to their offices. We find that there were still instances of knife attacks, as well as the continuing issue of dead bodies strewn on the streets in some areas. Shri Sarat Bose gave a warning that the overall situation continued to be very dangerous.

On 20th, Jugantar’s headline read that three thousand had died and thirty-three hundred injured over the past three days of the Calcutta Riots. One could sense a semblance of normalcy returning – tram services began in south Calcutta, special arrangements for ration were being made in relief camps, and lorries were put in action to transport government employees to their offices. We find that there were still instances of knife attacks, as well as the continuing issue of dead bodies strewn on the streets in some areas. Shri Sarat Bose gave a warning that the overall situation continued to be very dangerous.

Amrita Bazar Patrika declared that the city was “quieter,” while reporting that “stinking” corpses littered the city. We find a piece that the “Daily Worker,” the British communist mouthpiece, had blamed the entire affair on the failure of the Viceregal cabinet delegation, which it claimed had forced the Muslim league to desperate measures.

In neither Jugantar nor Amrita Bazar Patrika, we find any mention of either Gandhiji or Nehru commenting on the carnage of the past few days.

Back to the present

As I closed the tab of the National Digital Library (https://ndl.iitkgp.ac.in/), my mind was overcome with immense sorrow. Were those days really different from our present times? The sequence of events, the pattern of reporting, the responses from the institutions and the political establishment – all rung disconcertingly familiar. The medium of information may have changed, but the human experience remained the same.

Is this how India always was? Is no change possible? What meaning, what lessons can we glean from this dive into the past?

Itihasa-Purana is a living tradition, enriched by endless retellings, each with its own regional and local flavors, yet exalting the same truth. This living tradition must expand to encompass our modern history too. But what can we do while we wait for a modern Vyasa to compose the tale of our times?

The answer is simple. We must remember. We must never forget. Stories and paintings and cinema and poems and tweets – we must use all the means at our disposal to keep the flame of this memory alive. We must create authentic cultural artifacts that store these memories and the emotions attached to them.

From generation to generation, we must transmit our stories- our pain, our victories, our illusions, and our travels – we must talk about it, we must discuss it threadbare, among friends and families and fellow Indians, with respect, concern, and empathy, until we all discover a common thread that binds us all together as Bharatiyas.

In that public and personal ritual of remembrance, I am convinced that we will find wisdom if our sadhana is sincere and true.

Perhaps, that is how our civilization will survive.

Read more articles on Direct Action Day

Image Credit: Swarajmag

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.