Beginning as natural interest of people in enjoying themselves, singing and dancing took the form of a well-developed classical art in India, with social, religious and ceremonial significance. The various texts on the sastra of Natya record the development of music and dance, displaying the influence of historical events. It has been a long evolution through foreign invasions, shift in religious purpose, social and economic conditions that drove traditional theatre to folk styles and Devadasi traditions. This series of articles traces the relevance and history of performing arts in Indian tradition.

- Early Beginnings

- Ancient Indian Theatre

- Rasa Experience in Indian Aesthetics

- Repertoire of Indian Classical Dance

- Decline in Classical Arts

- Modern Revival

1. Early Beginnings

I. Introduction

Dancing is seen as a spontaneous expression of exuberance among all creatures. The onset of spring season after the cold winter, appearance of monsoon clouds after the heat of summer, courtship, meeting a loved one, winning a prize, the occurrence of any happy event, all induce a person to jump with joy and burst into dance. Music and dancing are characteristics of all societies, ancient or modern.

From spontaneous, rhythmic movements came more structured, formalised dancing that required training and practice, early in India. Thus was born classical dance forms that showed systematic training and creative freedom. From the early times of the Vedic period we have references to the three aspects of formalised dancing – trained individuals for dancing in functions, ritual dancing in ceremonies and the professional dancer. When dancing is referred to as a vocation, it indicates its popularity and demand in society. The earliest references to dancing indicate the secular nature of the art – it is spoken of as an amusement, an entertainment at its best, and an instrument of indiscipline, temptation and vice at its worst[1].

In the Purāņic period, music and dancing became an integral part of festivities of many kinds along with colourful robes, ornamentation using flowers and jewellery, rangoli, incense, ritual worship and feasting. Just as camphor, fruits, flowers, incense, lamps, cool water, silks, naivedya and sindhūr were offered to the Deity in temples as a gesture of love and devotion, so were songs, stotra and stuti compositions, music and dance also offered. Over the centuries, these became part of the daily rituals in many temples, codified in the Agamas. Gītaṃ, vādyaṃ, nŗtyaṃ and nāṭyaṃare among the sixty-four kalās or arts mentioned in texts such as Śiva Tantra and ŚukraNītiSāra. (Please see NruthyaLakshanam, p 39 for full list.)

Dance is said to be the most beautiful embodiment of the dedication that a devotee can offer. Every activity of the devotee is dedicated to God as a sacrificial offering. An artiste viewed his creation as a dedication to cosmic well-being. The performance was likened to a Vedic yajna, an offering to the cosmic powers that enable us in our activities.

Many Natya texts discuss the occasions in which music and dance formed part of the festivities. The Nŗttaratnāvalī mentions sacrificial rites, marriage, coronation, entering a new city, house-warming, water sport, union with beloved, ordinance (solemn vow), birth of a child, voyages, festivals, celebrations, victory, attainment of desires, propitiation to Gods, etc. as suitable occasions for auspicious dance leading to prosperity.

“त्यगोद्वाहमहाभिषेकनगरीवेश्मप्रवेशोदक-

क्रीडासुप्रियसङ्गमव्रतमहादानात्मजोत्पत्तिषु।

यात्रापर्वपरीक्षणोत्सवजयानन्दप्रतिष्ठोहित-

प्राप्तिष्वभ्युदयायनृत्तमुचितंस्याद्देवपूजादिषु॥१/ १८॥“

tyāgodvāhamahābhiṣekanagarīveśmapraveśodaka –

krīḍāsupriyasańgamavratamahādānātmajotpattiṣu|

yātrāparvaparīkṣaņotsavajayānandapratiṣṭhehita –

prāptiṣvabhyudayāyanŗttamucitaṃsyāddevapūjādiṣu|| 1|18

II. Early Literary References

Since early times, dancing has been a part of festivities and celebrations, even funerals, in many societies around the world and gained importance in both its ritual aspect and secular purpose. For ceremonial occasions, it was important for the participants to understand their role to give the ceremony completeness and proper significance. The secular aspect of entertainment, viz. relaxation and moral instruction, the avowed purpose of the performing arts, also required structure, rehearsal and planning.

Vedic literature has frequent references to dancing – the Gods are described as accomplished dancers. In the vast expanse of sky where clouds gather in many layers, Indra is described as dancing with skill and grace, sometimes ceremonially and sometimes for pleasure. Nearly half the hymns in the Rg Veda are dedicated to him as the King of the Gods, Devendra. Powerful, valorous, golden and benevolent, he battles the malevolent monster of drought, Vritra, year after year to bless the parched earth with rain that brings prosperity to mankind. He is armed with bow and arrow, the lightning is his weapon; he is of beautiful form and a glorious dancer. (I. 130.vii, II. 22. iv)

इन्द्रइन्नोमहानांदातावाजानांनृतुः।

महान्अभिज्ञ्वायमत्॥ (RgVIII. 92. iii)

Indra is indeed the great giver of much food; he is praised as the great dancer and one who enables others to dance and is invoked for prosperity. TheMaruts, Ashvins and other Devas were all described as delighting in dance. Radiant in appearance they are excellent dancers and victorious in battle. (V. 52.xii) The Gandharvas were celestial beings who were skilled in the art of music. The Apsaras were their consorts, experts in exquisite singing and dancing. They were the favourite musicians in Indra’s court. They rejoiced at the victories of earthly heroes and through song and dance showered their benediction on them. The fine arts were referred to as Gandharva Kala in early literature. (X. 123. v, VII. 33. xii)

The musicians and dancers envisaged in the earliest literature would surely be modelled on the beautiful ladies who were the epitome of grace in a society that valued the arts and cherished the skilled courtesans. This indicates that dancing as a vocation was popular and that there were professional dancers and actors.

Among the most beautiful poetry in the Rg Veda is the description of the youthful Goddess of dawn, Ushas, dancing across the skies before sunrise, her whirling red robes billowing across the heavens. She is a graceful dancer, ever fresh and ever young each day, heralding the sun, Surya, before his daily sojourn across the sky.

अधिपेशांसिवपतेनृतूरिवापोर्णुतेवक्षःअस्रेवबर्जहम्।

ज्योतिर्विश्वस्मैभुवनायकृण्वतीगावो न व्रजंव्युषाआवर्तमः॥ (RgI.92.iv)

Secular poetry reflects music and dance as part of marriages, funerals, harvest festivals, sacrifices and communal gatherings in the Ŗg Veda. In these hymns, we even find the beginnings of dramatic literature and mention of nŗtu, the professional dancer, and nata, the actor. The Sama Veda mentions the concept of Mārgī and Deśī types in music and dancing – this forms the first reference to classical and popular styles in performing arts. Margi was associated with sacred music in ritual while Desi was the popular music in society. Being skilled in music and dance was considered a gift from the Gods.

It is known that singing with instrumental accompaniment was part of the arrangements during yajna; there are references in the Vedas which mention the specific intervals in ritual procedure during which the wives of the Yajamana and priests would sing songs. As these songs are not recorded in the Vedic literature itself, we can assume that they came from the society, or “loka” as designated in Sastra. It is possible that dance performances also found place in the festivities associated with the performance of large yajnas over many days. The Upanishads also refer to music and dancing, at times as a seduction, and at times as a discipline of serious study.

“Here is a picture of a happy society where once work is finished people sit together over a drink. Their wives and maidens attired in gay robes set forth to the joyful fetes: boys and girls hasten to the meadow, when forest and field are clothed in fresh verdure, to take part in dancing. Cymbals sound, and, seizing each other by the arm, men and women whirl around until the ground vibrates and clouds of dust envelope the gaily moving throng. The meeting place for all the collective festivity is the samana. This word is used in many senses, including that of an assembly for festivity: women go to it to enjoy themselves (X. 55. V); young women also go there to seek their husbands, and courtesans go to make profit by the occasion. Whatever the nature of these dances, and however popular and folk in character these assemblies might have been, it is evident, through references to meeting places such as these, that the dancer and the courtesan were an essential part of this festivity.” – (Vatsyayan, page 152)

By the period of the epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata, dancing was well established with all the techniques and contexts that we associate with classical arts even today. Innumerable musical instruments are referred to, with minute variations, for example, in stringed instruments or percussion. Many are the occasions where dance and music are described as part of the celebrations, lending auspiciousness and joy. Rama and Ravana are both extolled not only as formidable warriors but also as skilled dancers. The story of Ravana, a great devotee, pleasing Lord Shiva by playing the veena is well-known. Royal celebrations are described as including drums, music and dance all over the city. When Bharata returns to Ayodhya after Rama’s exile, the city he enters is described as silent with the absence of drums, lutes and bells of dancing. Again, when victorious Rama returns to his capital after the long years of exile, the city is said to reverberate with music and drums, with celebrations everywhere with groups of dancers.

In the Bala Kanda of Valmiki Ramayana, Sri Rama is described as expert in all the weapons and charms of the Gods, demons and men, erudite in all branches of learning, well-versed in the Vedas and Vedangas, the best on earth in the Gandharva arts (music and dance), gracious to fellowmen, kindly, of cheerful temperament and great intelligence.

देवासुरमनुष्याणांसर्वास्त्रेषुविशारदः।

सम्यग्विद्याव्रतस्नातोयथावत्साङ्गवेदवित्॥३४॥

गान्धर्वेचभुविश्रेष्ठोबभूवभरताग्रजः।

कल्याणाभिजनःसाधुरदीनात्मामहामतिः॥३५॥ (BK. 2. 34, 35)

When Hanuman entered the palaces of Ravana in Lanka, looking for Sita, the wonderful descriptions of the many musicians, dancers and musical instruments point to their importance in a prosperous and cultured society. The Sundara Kanda describes him going from mansion to mansion, delighting in all that he saw and enjoying the wonderful music that was defined with notes of the three octaves emanating from the three regions (stomach, chest and throat) of the singers. He saw beautiful ladies like the Apsaras of the heavens, the bells of their waistbands and anklets tinkling as they moved.

राघवार्थेचरञ्श्रीमान्ददर्शचननन्दच।

भवनाद्भवनंगच्छन्ददर्शकपिकुञ्जरः॥९॥

विविधाकृतिरूपाणिभवनानिततस्ततः।

शुश्रावरुचिरंगीतंस्त्रिस्थानस्वरभूषितम्॥१०॥

स्त्रीणांमदनविद्धानांदिविचाप्सरसामिव।

शश्रावकाञ्चीनिनदंनूपुराणांचनिःस्वनम्॥११॥ (SK. 4. 9-11)

In the Mahabharata also there are a vast number of references to music and dance. Arjuna had the opportunity to learn the arts from the Gandharvas and Apsaras, which served him well when he spent the thirteenth year of exile as the dance teacher Bŗhannalā, to the ladies of King Virata’s court including the princess and the queen.

In Buddhist literature the birth of Lord Buddha is said to have been celebrated with festivities that included five hundred musicians. Treatises such as Mahavastu and Lalitavistara abound with references to men and women who were accomplished in the arts of writing, composing poetry, music and dancing.

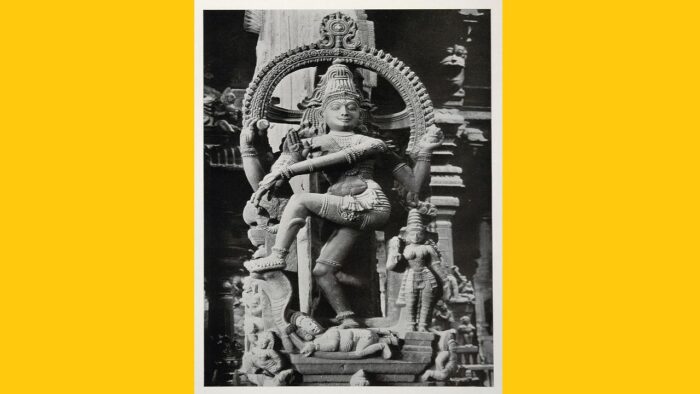

In thePurāņas the grace and elegance of a dancer take the imagination to conceiving cosmic activity itself as the dance of the Supreme. Lord Nataraja symbolizes the cosmos and His dance pose is its motif. In some traditions, such as Kathak, the basic dance syllables are regarded as the sound of Lord Krishna’s dancing feet. We see that all sections of society participated in dancing and also cherished witnessing recitals by accomplished artistes trained in the art. Men and women participated in dance during celebrations and festivities. They also donned a variety of roles on stage performances of plays.

III. The Significance of Nāṭya

Throughout much of history, the common people did not read books in India as they were rare and hardly required. Beginning with the chanting of the Vedas which were only taught orally, ours is a tradition that lays emphasis on the sounds of language. The common people did not even require to be literate, learning much about the world around us by narrating stories, listening to grand poems, reciting slokas and singing songs. Even the serious sastras were transmitted by oral lessons with the help of Sutras which were easy to learn by rote and contained entire lessons in a nutshell. While written scripts were known and texts had been written and preserved, it was hard to come by palm leaf manuscripts which were painstakingly written by hand. The oral tradition was active in transmitting information of a wide variety in an active society.

The theatre played a large role in taking stories, narratives and concepts of ethics and philosophy to the people. Itihasa and Puranas are said to extend the philosophy of the Vedas through stories and narrations, teaching what is dharma and what is not. The Puranic stories, from which most Natya performances were drawn, did much to contribute to the social and spiritual well-being of all classes of people.

The origin of Natya is explained in the beginning of the Natyasastra. It is said that once upon a time, all the Gods went to the Creator Brahma, requesting for something soothing that was pleasing to the eyes and ears, that would heal troubled hearts, offering balm to minds wearied by the trials and tribulations of life. After meditating on the request, Brahma decided to compose a fifth Veda, taking the essence of all the arts and sciences and which not only delight all sections of society but impart enlightenment too. He took words from the Rg Veda, music from Sama Veda, gestures from the Yajur Veda and emotions from the Atharvana Veda and composed the Natya Veda. That it is called the fifth Veda refers to its importance as well as comprehensiveness of the knowledge that it encompasses. He gave it to the Gods and asked them to practice it with patience, intelligence, diligence, and self-control. But after pondering over it, Indra submitted that they did not have the qualifications for the fine art and said that only the Sages would be able to nourish this art as only they had grasped the Vedic knowledge and were also self-controlled. Thus it came about that Brahma entrusted the Natya Veda to Bharata and his hundred sons, or pupils.

Thus the fine arts that are encapsulated in performing arts aim to offer entertainment as well as spiritual guidance to the audience. Modern concepts such as relaxation and ‘de-stress’ were anticipated by the Natyasastra several millennia ago in India. The popularity and occasions of drama are described thus in the Natyasastra:

“वेदविद्येतिहासानामाख्यानपरिकल्पनम्।

श्रुतिस्मृतिसदाचारपरिशेषार्थकल्पनम्॥१/ ११९॥

विनोदजननंनाट्यमेतत्भविष्यति।

देवतानामसुराणांराज्ञामथकुटुम्बिनाम्॥१/ १२०॥“

“Profound with the learning of the Vedas, composed with the stories of the Itihasas and Puranas, to impart instruction of Shruti, Smrti and ethical conduct, this Natya will provide entertainment to Devas, Asuras, Kings and families.” N.S. I.119-120

In the Fourth Chapter we see:

“प्रायेणसर्वलोकस्यनृत्तमिष्टंस्वभावतः।

मङ्गल्यमितिकृत्वाचनृत्तमेतत्प्रकीर्तितम्॥४/ २७०॥

विवाहप्रसवाहप्रमोदाभ्युदयादिषु।

विनोदकारणंचेतिनृत्तमेतत्प्रवर्तितम्॥४/ २७१॥“

“Dance is mostly enjoyed by everybody as it is in one’s nature to do so; this (pure) dance is also well-known as auspicious. This dance is to be enjoyed on the occasion of weddings, birth, celebration of joyous and prosperous achievements; it becomes a source of festivities and leisure and hence nrtta is cherished.”

Dance in performances had a twofold purpose – it was not only incorporated in drama for enhancing the aesthetic beauty but was also considered as sacred. Nrtta or pure dance, had ritual significance and auspiciousness on its own, augmenting the value of any performance. The very cosmos is said to be the dance of Lord Shiva.

The Nttaratnāvalī says in the introduction or eulogy to dance, that Lord Shiva who is without form, took corporeal manifestation as Naṭarāja in order to revel in the beautiful Tāņḍava dance, for, who would not be charmed by such a delightful form of dancing!

“………… भामनोऽपिसदाशिवाद्याकृतिभेदयोगे।

यत्कौतुकंकारणमाहुराप्तानृत्तंनतत्कस्यभवेत्सुखाय॥१/४॥“

śambhobhāmano.apisadāśivādyākŗtibhedayoge|

yatkautukaṃkāraņamāhurāptānŗttaṃna tat kasyabhavetsukhāya|| I.4

IV. Conclusion

The traditional theatre that the Natyasastra represents has been an epitome of Indian culture for over thousands of years. Natyasastra describes the origins of our dramatic traditions that mirror the social and cultural life of ancient times. It represents the ways of the world in language, dialect, customs, costumes and traditions. It speaks of the skills required in an actor to deliver a good performance in terms of physical fitness, voice control, clarity of diction and expression of emotions, addressing all the elements of stagecraft. In addition, it also speaks of the emotional sensibilities and acumen of the audience who should be capable of understanding and appreciating the performance.

As the Natya tradition is considered as a fifth Veda, taking the essence of the Rg, Sama, Yajur and Atharvana Vedas and as the performance is considered as a yajna in offering the finest of arts to the gods, point to the sanctity, sacredness and purpose of the art in pleasing not only mankind but the gods as well.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sanskrit Texts

Nāṭyaśāstra of Bharata Part One with Abhinavabhāratī (Chapters I to V).Sampoornanand Sanskrit University. Varanasi.

NŗttaratnāvalīofJāyasena. ed. Tr. V. Raghavan. Madras Govt. Oriental Series No.CVIII. University of Madras. Madras.

Ramayana of Valmiki (Eight Volumes with 3 Commentaries). Parimal Publications. Delhi. 1990.

Secondary Literature

Jayaa, Guru Natyavidushi. NruthyaLakshanam: A Sourcebook on Indian Classical Dance. Jayaa Foundation for the Promotion of Performing Arts. Bengaluru. 2016

Narayanan, Sharda & Mohan, Sujatha. Gitagovinda of Jayadeva: Study in Sahitya and Natya. DK Printworld. New Delhi. 2022.

Ramachandra Aiyar, T.K. A Short History of Sanskrit Literature. R.S. Vadhyar& Sons. Palghat. 2021.

Rangacharya, Adya. Natyasastra of Bharata – English Translation. MunshiramManoharlal, Delhi.

Vatsyayan, Kapila (1968) Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts. Sangeet Natak Academy. New Delhi.

[1]Secular here refers to art not involving the gods or adhyatmika.

Feature Image Credit: pinterest.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.