I. Sanskrit Theatre

The study of the arts can basically be done in two ways; one is by focusing on its intrinsic features and analysing the techniques and characteristics of practice, which are best understood by the practitioners of art. The second method is by studying the historical development influenced by socio-political and economic factors, which this article addresses in brief.

The style of classical theatre has been more on suggestion than realism, relying on poetically conveying a story through music and dance. The purpose of the performing arts was enjoyment and spiritual elevation, as the benedictory verse clearly indicates at the conclusion of the program. The occasions for dance were considered auspicious and celebrations most of the time, the contexts being royal courts or temple festivals. Serious and sombre reflections were sought more in prose and poetry than in drama.

“The extant masterpieces of Sanskrit drama belong to the flourishing period of Sanskrit literature, which is usually regarded as extending roughly from the fourth to the twelfth century of the Christian era. Recent researches have, however shown that the extant literature probably does not give a proper indication of its great antiquity.” (S. K. De: “Sanskrit Drama: General Characteristics”, in The Cultural Heritage of India, Volume V: Languages and Literatures, page 234)

“There were also certain other conditions and circumstances which seriously affected the growth of Sanskrit drama. From the very beginning the drama appears to have moved in a cultured environment, having been fostered by the patronage of the wealthy or in the courts of princes; like Sanskrit poetry, it believed in a tradition which insisted upon literature being a learned pursuit… Although various types of drama were theoretically distinguished, few old specimens have survived, making the question purely academic.” (S.K. De, page238-239)

The evolution of Sanskrit literature has always been hand-in-hand with Prakrit or Apabhramsha literature right from the beginning of the early centuries CE, as far as we know, in format, theme and structure. By the tenth or eleventh century CE, classical Sanskrit literature in Kavya and Sastra-s of all kinds had reached extremely high levels of sophistication and complexity and the vernacular languages also developed a stronger literary presence. From the natya texts and the literature itself, we find a decided shift from the Rupaka format of yore to several types of smaller productions called Uparupaka, which presented dance more predominantly than drama.

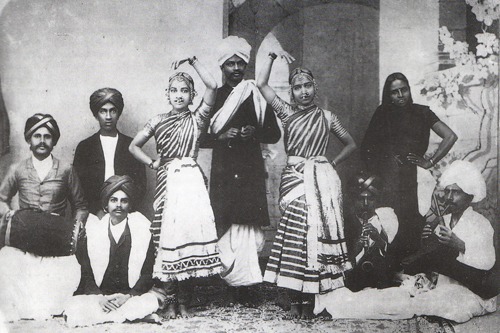

(Figure 1: Credit: indiatimes.com)

Throughout the early centuries, the various kingdoms of Hoysala, Rashtrakuta, Chalukya, Kakatiya, Yadava, Chola, Chera, Pandya and even Sena rulers were intimately connected by frequent marriage alliances in southern India. The exchange of musical and dance traditions as well as the migration of artistes is known to have occurred frequently – the different regions were not considered separate cultural areas notwithstanding the regional differences and preferences that added to the richness in variety. Many royal queens, notably Shanthala in Karnataka, were known to be expert dancers. Raja Raja Chola built the Brhadeeswara Temple in Thanjavur, considered a great centre of learning and the fine arts in 10th century AD. In the years that followed, a Chola princess married a prince of the Sena dynasty in Bengal-Orissa and took with her many dancers and musicians. The Senas were originally a Kshatriya clan from Karnataka who extended their kingdom to the north by defeating the Pala kings. Lakshmana Sena patronised the great poet Jayadeva who composed the sublimely exquisite Gitagovinda, a lyrical poem known as prabandha, meant to be performed with music and dance in c. 1185. Jayadeva is known to have lived in Kalinga, where he honed his skills in music and poetry in younger days. The period also boasts natya texts such as Nrttaratnavali and Sangitaratnakara that indicate the performing arts reaching extremely high standards, with the different districts vying with each other for excellence. Srngara was exquisitely delineated in all its nuances with beautiful lasya and laya.

The understanding of our classical arts is undergoing a huge revival and the current generation is fortunate to live in these exciting times. Most writers on Sanskrit drama in the twentieth century had little or no understanding of the techniques of stage presentation, music or dance. They tend to assess a play by its script alone, often labeling Sanskrit plays of later times as imitations, lacking in originality or dynamism. Several types of plays described in early texts such as Natyasastra that involved the common life of the people are termed as “theoretical discussions” simply because very few scripts have survived to our time. But absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. We have to imagine the practical reality of a mature society with the fragments of evidence that we do see now.

“If drama is the transference of human action on the stage, these works are not dramas, and very few of them are acceptable as stage-plays. Even considered as poems, their real value is obscured by convention and pedantry. It has been suggested that the natural progress of the art was obstructed and disordered, from this period onwards, by the depressing effect of Muhmaddan invasion and by the turmoil and uncertainty consequent upon it. As in poetry, so in drama, this is only partially true… The history of Sanskrit drama, therefore, does not close with the 10th century, but it loses genuine interest thereafter.” (S. N. Dasgupta & S.K. De: A History of Sanskrit Literature, page 447-448)

II. Wave of Invasions

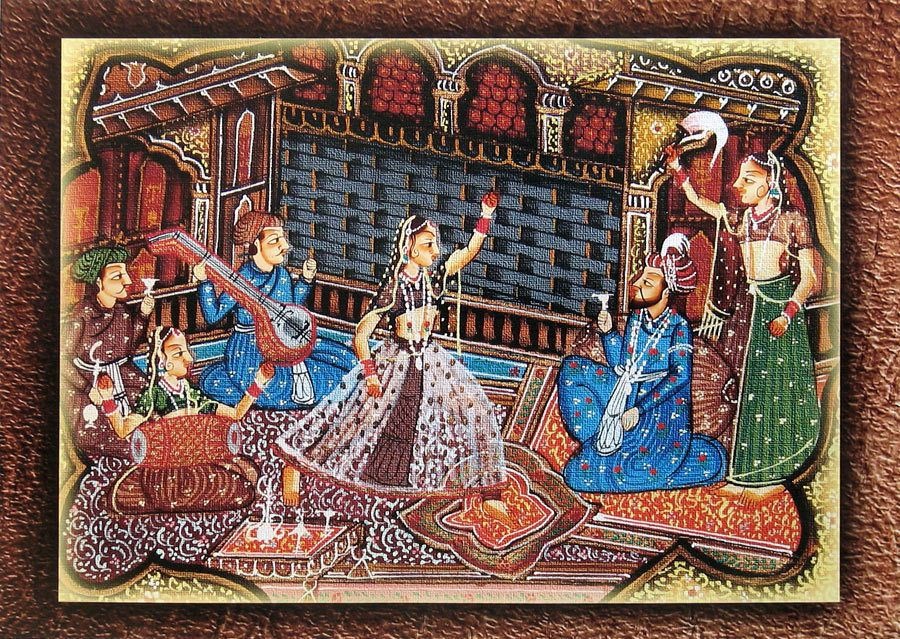

(Figure 2: Credit: Dolls of india.com)

We see that the fortunes of the performing arts rose and fell with the court and temple traditions. From the ninth century onwards, India came under a wave of invasions and in the political and social unrest. In North India, music underwent a sea-change, as did all art forms. The very purpose, goal and meaning of music shifted from a fundamentally spiritual pursuit to a pleasure-giving art. The foreign rulers modified the classical music according to their tastes and developed melodious new ragas for enjoyment and entertainment; Karnatic music continued to be preserved and practised with relative freedom. Over the next few centuries, variations in styles of presentation became so marked as to follow an entirely different grammar; the names of many ragas changed and there was great variation in terminology and technicalities, to the extent that it is very difficult to understand early texts today. But a common classical base can still be traced.

With the advent of foreign invaders in North India in the 10th century and the long periods of socio-political turmoil, most drama troupes were disbanded and the members dispersed into the countryside, seeking other means of livelihood. In the years of pillage and plunder that followed, the vast majority of manuscripts went up in flames or crumbled to dust. Drama troupes that presented stories based on the Puranas and epics had little place under foreign rule. They became relegated to folk arts in the districts, having lost relevance in urban centres. Perhaps the decline of theatre based on devotional themes prompted increased Bhajan and Satsang sessions in the rural areas. The very purpose, meaning and goal of the performing arts were shifting from spiritual to one of pleasure in the capital cities. The varied rasas such as vīra, bhayānaka, bībhatsa, karuņa or even hāsya in its customary context had no place in the aristocratic circles in urban centres. Only śŗńgāra was prized for its exquisite beauty and ability to give pleasure. A musician who was not attached to a court in some way or the other could hardly survive. The community of courtesans alone flourished.

III. Temple Traditions

Temple culture was well-nigh decimated, with the large temples themselves being destroyed in North India. This brought the religious dance traditions to a close. There were only small temples that the people prayed in the countryside that gave some continuity to devotional music, especially in vernacular languages. In the context of South India –

“The Dark Ages – After the glorious Pallava, Pandya and Chola dynasties, a dark phase marked the history of South India. The richness of the region attracted plunder and destruction. With cruelty and ruthlessness, the Hindu South was conquered by the Muslim forces of North India. From the middle of the thirteenth century for nearly a hundred years, the shadow of terror cast gloom on temples, and the cultural and social life of the South. Devadasis too faded into oblivion. There are no records to show what they did in this period. A few accounts of historians, mainly travellers, point to some of the invaders taking hundreds of dancers away as part of their loot to serve them in their own palaces in Central India.” (Lakshmi Viswanathan: Women of Pride: p 89)

Even the greatest of Saiva temples in South India, Chidambaram temple, has had a chequered career. The temple complex has seen changing fortunes in its long history, subject to plunder and destruction with the advent of foreign invasions. Malik Kafur is said to have carried away much gold and jewels along with artistes from Chidambaram in 1311 after his raids in many parts of Tamil Nadu. When his next invasion was rumoured to have begun, many temples across South India ceremonially buried their Nataraja and other icons deep in the earth to avoid desecration. Such bronzes and other artifacts are even now being discovered after many centuries.

(Figure 3: Credit: Pinterest)

There have been several unfortunate occasions in history when the worship rituals have been interrupted in Chidambaram. The Madurai Sultanate, which broke away from the Delhi Sultanate, in turn imposed heavy taxes on Chidambaram temple. Relief came only after the Vijayanagara and later, Nayaka kings came to power and supported the temple, carrying out renovations and improvements.(Incidentally, the Nayaka kings also rebuilt the Kapaleeswra temple in Mylapore, Chennai, which had originally been on the seashore and demolished by the Portuguese.) During European colonial days, Chidambaram came in the crossfire of the British and French forces that were vying for supremacy in India and the temple complex was used as a garrison for the British, suffering much damage and ruin to its buildings. According to British reports, Chidambaram temple town had to bear the “brunt of several severe onslaughts’ ‘ between the British and French colonial forces in the 18th century.

IV. Notes from History

While there are a large number of examples, we look at just two quotations below from the historians of the 14th century, as a window into the conditions of those times.

(Figure 4: Credit: Pinterest)

Measures against the Hindus. Page 23.

“Ala-ud-din next turned his attention to check the power and influence of the Hindu officials named khūt, chaudhrī and muqaddam… These three classes of people were hereditary collectors of revenue on behalf of the King and it was alleged that they appropriated to themselves as much of the State revenue as they could, evaded payment of taxes and even ignored the Government. As the chronicler describes, they ‘ride upon fine horses, wear fine clothes, shoot with Persian bows, make war upon each other, and go out hunting…. and hold drinking and convivial parties.’ ‘Ala-ud-din sought to curb their powers by depriving them of all the special privileges which they enjoyed at the expense of the State. The standard of the revenue-demand was raised to one-half of the gross produce. The perquisites realized by the chiefs were abolished and all concessions withdrawn; they were to pay land-revenue at the full rate and their land was brought under assessment; and all discriminations were done away with between the chief and the humblest peasant (khūt and balāhar). The land revenue was to be assessed by the method of measurement on the basis of standard yields… Besides, the King imposed two new taxes: a grazing tax on all milch cattle and a house tax. As a result of these legislations, the objectives of the king were realized, though it may be questioned if the measures were economically sound. The motives of Ala-ud-din were decidedly political. The high revenue-demand impoverished the peasants so much that the very source of the revenue-collectors was dried up while the assessment of their land reduced them to the condition of peasants; and besides the loss of perquisites they had to now pay additional taxes. In a sense the conditions were favourable to the peasants, as the revenue collectors also had to bear the burden along with them. If the contemporary chronicler is to be believed, these regulations were strictly enforced. The chiefs (khūts) and the headmen of parganas as well as villages – they were all Hindus – were so much impoverished that no gold or silver was to be found in the houses of the Hindus; they could not afford to procure horses or weapons; and their wives had to serve for wages in the houses of the Muslims. “The people,” we are told by Barāni, “were brought to such a state of obedience that one revenue officer would string twelve khūts, muqaddams and chaudhrīs together by the neck and enforce payment by blows.” (S. Roy: “The Khalji Dynasty”, in The Cultural History of India- Vol VI – The Delhi Sultanate, page 23)

Of Sultan Firuz Shah who succeeded Mohammed-bin-Tughlaq, R.C. Majumdar records this account of a temple festival:

So far as the Hindus were concerned, the following passage gives an idea of his bigoted attitude:-

“The Hindus and idol-worshippers had agreed to pay the money for toleration (zar-i-zimmiya), and had consented to the poll tax (jizya) in return for which they and their families enjoyed security. These people now erected new idol-temples in the city and the environs in opposition to the Law of the Prophet which declares that such temples are not to be tolerated. Under Divine guidance I destroyed these edifices and killed those leaders of infidelity who seduced others into error, and the lower orders I subjected to stripes and chastisement, until this abuse was entirely abolished. The following is an instance:- In the village of Malūh there is a tank which they call kund (tank). Here they had built idol-temples, and on certain days the Hindus were accustomed to proceed thither on horseback, wearing arms. Their women and children also went out in palankins and carts. There they assembled in thousands and performed idol worship. This abuse had been so overlooked that the bazār people took out there all sorts of provisions and set up stalls and sold their goods. Some graceless Musalmāns thinking only of their gratification, took part in these meetings. When intelligence of this came to my ears my religious feelings prompted me at once to put a stop to this scandal and offence to the religion of Islam. On the day of the assembling I went there in person, and I ordered that the leaders of these people and the promoters of this abomination should be put to death. I forbade the infliction on any severe punishment on the Hindus in general, but I destroyed their idol temples, and instead thereof raised mosques.”

Firuz also cites another concrete instance where the Hindus who had erected new temples were put to death before the gate of the palace, and their books, the images of deities, and the vessels used in their worship were publicly burnt. This was to serve “as a warning to all men, that no zimmī could follow such wicked practices in a Musalman country.” Other instances are given by contemporary writers. ‘Afif gives a graphic description of one such case. A Brahman of Delhi was charged with “publicly performing the worship of idols in his house and perverting Muhamaddan women, leading them to become infidels”. The Brahman was told that according to the law he must “either become a Musalmān or be burned”. The Brahman having refused to change his faith, “was tied hand and foot and cast into a burning pile of faggots”. ‘Afif, who witnessed the execution, ends his account by saying: “Behold the Sultan’s strict adherence to law and rectitude, how he would not deviate in the least from its decrees”. (R.C. Majumdar: “Firoz Shah”:page 108-109)

After the fall of the Vijayanagara empire, the scholars, poets, musicians and dancers fled in droves to the regions further south, seeking asylum in the Nayaka and later the Maratha kingdoms of Tanjavur. This gave a fillip to the arts there, the effect of which is seen in Karnatic music, Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, BhagavataMela and even MohiniAttam. The flourishing arts under the patronage of Nayaka and Maratha kings gave impetus to not only music and dance but also poetry and literature leading to a huge resurgence of compositions in court dancing and devotional items, with Padams and Javalis composed in Tamil and Telugu. Sanskrit compositions were of the Ashtapadi type, expressing Srngara bhakti that was suitable for dance. Karnatic music also reached its pinnacle with the Trinity of MuthuswamyDikshitar, Thyagaraja and ShyamaSastri who composed in Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century in Southern Tamil Nadu.

During the period of British rule in India, the foreign administrators regarded native music as uncivilized and gave it no encouragement. While Karnatic music continued to thrive in the devotional aspects, it struggled to survive in the secular activities of society. The country was also in the throes of poverty for a prolonged period. Indian music fell into the hands of people of dubious distinction and respectable families were not eager to have their children associate with this art.

The secular, festive, ceremonial and official occasions for classical dance found little patronage in public life. Under British imperial rule, Indian dancing was labeled immoral under the sway of Anglicised education and missionary zeal. Dr Meenakshi Jain records how Hindu practices, especially Sati and Devadasi system, were exaggeratedly portrayed as evil and exploitative by the missionaries to induce the British Parliament to allow proselytization. Only the religious aspect of dance survived owing to its sacred association with rituals for the deity and traditional patronage in the temple. Due to economic duress, the lives of the devadasis suffered degeneration. In the twentieth century the ethics of a minor girl’s family dedicating her life to a vocation of dancing came under question, although the practice of apprenticing children in various vocations was common all over the world in bygone times. Under the social reformers of the time, the Devadasi system was abolished in 1947 by law, bringing to a close the long tradition of dance in temple rituals.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chatterji, Suniti Kumar (General editor) (First edition, 3 volumes, 1937. Revised second edition 1978) The Cultural Heritage of India, Volume V: Languages and Literatures. The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. Calcutta.

Dasgupta, SurendraNath& De, Sushil Kumar (first edition 1947, second ed. 2017) A History of Sanskrit Literature. Classical Period. MotilalBanarsidass. Delhi. (First edition Calcutta University)

Jain, Meenakshi (2016)SATI: Evangelicals, Baptist Missionaries and the Changing Colonial Discourse. Aryan Book International. New Delhi.

Majumdar, R. C. (General Editor) (1st edition 1960, 4th edition 1990) The History and Culture of the Indian People Vol VI: The Delhi Sultanate. BharatiyaVidyaBhavan. Bombay.

Narayanan, Sharda (2020) “ThiruMayilai: The Itihasa of Mylapore” online article.https://intellectualkshatriya.com/thirumayilai-the-itihasa-of-mylapore/

Narayanan, Sharda & Mohan, Sujatha.(2022).Gitagovinda of Jayadeva: Study in Sahitya and Natya. DK Printworld. New Delhi.

Narayanan, Sharda & Rathnavel, Madhangi (2021) Tirumurai: Glimpses into Tamil Saiva Poetry. AmbikaAksharavali. Chennai.

Vishwanathan, Lakshmi (2008) Women of Pride: The Devadasi Heritage. Lotus Collections, ROLI Books Pvt Ltd. New Delhi.

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.