The mythology of Daksha Yagya remains central to the origin and the substanance of the Shakta form of worship and particularly to the establishment of the Shakti Peethas across the sub-continent. It is believed that when a distraught Mahadeva performed the Rudra Tandava with the corpse of his wife Sati on his shoulders, her body disintegrated and fell across the Indian subcontinent. Each area in which a part of her body fell, became a Shakti Peetha where the Devi was consecrated in some form. The number of Shakti Peethas in India are often a topic of contention, but there is no ambiguity about the 18 Maha Shakti Peethas where the divine mother is worshipped in her various forms. Adi Shankaracharya in his Ashta Dasa Shakti Peetha Strotam laid down the names of the 18 Maha Shakti Peethas spread across multiple states of India and Sri Lanka. Each of these deities including the Ma Biraja in Odisha, Ma Kamarupa in Gauhati, Ma Jwalamukhi in Himachal Pradesh and Ma Shankari Devi in Sri Lanka are still worshipped in their respective temples and devotees throng their abode through the course of the year.

It is that time of the year when we are remembering Shakti, the divine mother, the Sri Mata and celebrating the divinity embedded in the female form all across the country. The 18 Maha Shakti Peethas along with the numerous Devi temples spread across the length and breadth of the country are resplendent in the glory of the Adi Shakti that resides there. But, in the midst of all this, there is one Maha Shakti Peetha, a temple central to the Shakta tradition, the temple where the Devi resided as the Goddess of knowledge and learning that remains far away from the celebrations. The temple lies abandoned, the Vigraha of the Devi destroyed and the stories of the temple as the centre of learning and education gradually being pushed into the pages of history. And while we celebrate, it is important to relive and remember the enormity of what we have lost and resolve to regain the lost Goddess.

Namaste Sharda Devi, Kashmira Puravasini,

Twamaham Prarthate Nityam, Vidya Danancha Dehime

One of the 18 Maha Shakti Peethas lies at the base of the Shamshabari range at the confluence of the rivers Madhumati and Kishanganga. Nestled at the base of the beautiful mountain range in her homeland of Kashmir, was the Goddess of Knowledge, Devi Sharda. The belief that the right hand of Devi Sati, the hand symbolic of writing and learning fell in this holy land also made it the abode of the Goddess Saraswati in the form of Sharda. It is said that Kashmir at a point was known as Sharda Desha and the temple was a hub of learning and erudition. The small village of Sharda did not just have the temple of the Devi but was also home to one of the largest universities in Central Asia. The Sharda script which is native to Kashmir is named after this form of Shakti.

Kashmir is known as one of the oldest Shaiva Kshetras but there is a strong Shakta tradition in the state which is often ignored. And this Shakta tradition owes its origin to the presence of Devi Sharda. The earliest mention of the shrine can be traced to the Nilamata Purana which particularly elaborates on the various tirthas and peethas of Kashmir. The Sharada Mahatmya tells us the story of Muni Shandilya worshipping Sharada Devi. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini also has a detailed description of the Goddess and the shrine at the confluence of the two rivers. One of the most vivid accounts of the temple has been provided by Aurel Stein who has translated Kalhan’s Rajatargini in a chapter titled, ‘The shrine of Sharda’.

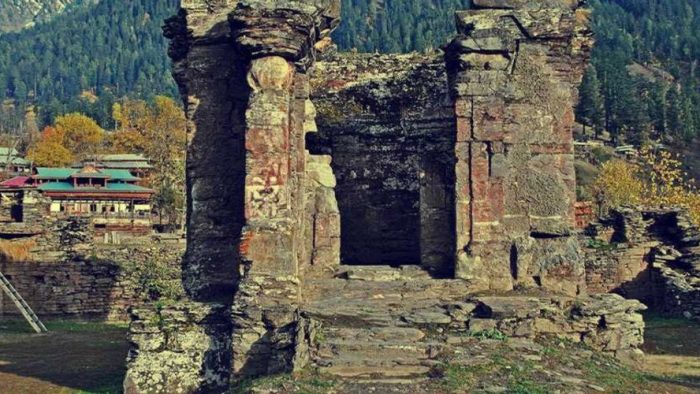

But today, the abode of Devi Sharda lies desecrated and abandoned in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. After the mass migration of Kashmiri Hindus from PoK, the temple was completely cut off from the devotees and gradually started falling into disrepair. The temple lies unattended since decades, the deity or Vigraha of the Goddess is long gone and the earthquake of 2005 has even made the structure absolutely vulnerable. There are even instances of theft which have come to light with one of the Kundas from the temple being located at the Abbas Institute of Medical Sciences, Muzaffarabad. Unlike the other big Shakti Peeth in Hinglaj, Balochistan, Hindus of Pakistan have almost completely stopped visiting the shrine of Devi Sharda. Once the seat of learning and education, the tiny village of Shardi, has almost become a footnote in the tumultuous history of Kashmir. The one thing that keeps the allure and the longing of the shrine alive are the stories and oral traditions that pass down generations in Kashmiri Hindu households.

But, even oral traditions are dwindling with time. The last devotees who visited this Maha Shakti Peeth did so before independence and the collective memory of the shrine is at a risk of getting lost. One of the last documented accounts of the temple is by nonagenarian Shambhunath Thusu. It is unclear whether he has seen the temple but he has provided a thorough description of the Vigraha. The Vigraha is a naturally occurring stone plinth about six feet long and seven feet wide. Another old timer account of the temple also provides a similar account and states that there was an entrance of the Western side of the temple and a Shiva Lingam outside the sanctum sanctorum. Another account came from Justice S.N Katju who visited the temple in 1935. He added that “the steps leading to temple were twisted like an earthquake had battered them”. The details are sparse now and the images available make it difficult to imagine the temple in its days of glory.

Brigadier Ratan Kaul in his paper ‘Abode of Goddess Sharda at Shardi’ discusses the elaborate preparations for the Sharda Peeth Yatra which used to happen regularly before 1947. He has drawn from the accounts of Pandit Bhawani Kaul and Pandit Harjoo Fehrist who had undertaken multiple pilgrimages to Shardi in the late 1800s and whose accounts survived as oral traditions in Kashmiri Hindu households. The pilgrimage used to take 9-10 days on foot from Sri Nagar and pilgrims used to keep joining the group as they passed through major halting locations.

One of the most recent accounts of the visit to the Sharda Peeth is provided by A.R Nazki in the book ‘Cultural Heritage of Kashmiri Pandits’. Nazki visited the Peeth from Muzaffarabad in PoK in the year 2007 and in the chapter titled ‘In search of Roots’, he describes the treacherous yet tranquil terrain to Shardi made even more inaccessible after the earthquake of 2005. Mr. Nazki describes the state of ruin of the temple and details out all that has been able to bear the neglect of decades. He writes of the faint inscriptions in the Sharda script on the entry pillar of the temple and remnants of quarters where the Pujaris must have lived in the days gone by. Only the left half of the archway stands and the door and the roof of the temple are no longer there. The university which used to thrive at Sharda has no remains and apparently there used to be a pond with healing water in the compound which has since dried up. Nazki writes, “The building presented a picture of ruin and is a victim of neglect, its academic and instructional importance appear to be only a dream”.

The cultural sociologist, Ann Swidler in her famous article, ‘Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies’ talked about a tool kit of habits and styles which people use to strategize their actions. Religious beliefs and practises are a major part of that tool kit which determine our actions, behaviors and decisions. Hence, our religious practises define us on a daily basis and alienation from that has a profound impact on the way we imagine ourselves. The cultural moorings of a community cannot be understood without understanding the way in which they have developed with the help of their religious beliefs and practises. This is just one of the ways of assessing what being cut off from essential religious beliefs and practises is like.

The enormity of the loss of losing the Temple of Devi Sharda needs to be put into perspective especially because it has been nearly 7 decades since the temple has fallen into disrepair and abandonment. Our temples are the link to our heritage, our shared history and our identity. When I started reading and learning about the temple, I could only go back to what I know and relate easily to. How would it feel to be a practising Hindu in Odisha and not have the temple in Puri to visit or to see it desecrated? Or to be a Sikh residing in India and never being able to visit Nankana Sahib and seeing it in disarray? How would it feel to be cut off from a physical manifestation of your identity and culture and see it in ruins out of your reach? How would it feel to celebrate Basant Panchami with the Goddess of Knowledge being uprooted from her home for decades? How would it feel to celebrate nine days of Shakti. knowing that we have been alienated from drawing our strength from our roots? Whether you measure this in religious or cultural terms or just in terms of collective identity, this is a loss beyond measure.

I met Dr. Sushma Jatoo, a Sanskrit scholar working with the IGNCA and asked her about the extent of the desecration of the temple. She refused to use the word desecration but admitted that the Vigraha of the Goddess is no longer present in the temple and the shrine remains unattended. Sometimes, semantics is the only way of keeping memory alive and the importance of Devi Sharda in the everyday lives of Kashmiri Hindus could be gauaged from Dr. Jatoo’s reluctance to use the word ‘desecration’. Desecration implies profaning or polluting something beyond repair and probably to the Kashmiri Hindus like Dr. Jatoo, there is no way that the temple of their beloved Goddess can be profaned. In the face of all that the Hindus of Kashmir have borne, even language is a form of resisting complete erasure.

Therefore, Hindus and Kashmiri Hindus in particular wait for the recovery of the temple. And that would begin by ending the alienation of the temple and beginning to revive the temple again. But, the Neelum valley is one of the most disturbed areas in the current political atmosphere and the government of Pakistan is against issuing visas to any Indian citizens to visit the area. It is against these odds that a group called the ‘Save Sharda Committee’ comprising of Kashmiri Pandits have started a campaign to revive the pilgrimage to Sharda Peeth. The demand is along the lines of the pilgrimage to Nankana Sahib in Pakistan which allows the Sikh community staying in India to remain rooted to their identity and culture. Together with another group called the All Pandits Migrants Coordination Committee (APMCC), the activists have already met the ex-CM Mehbooba Mufti and are planning to petition to the Prime Minister. They have also reached out to the MoS PMO and MP from J&K Mr. Jitendra Singh, the Minorities Affairs Minister Mr. Muqhtar Abbas Naqvi and the Shankaracharya of Shringeri Mutt with their demands.

Our deities live with us. Not just their legends. Our temples sustain our communities. They don’t just turn into museums or relics. The Goddess of Kashmir is lost. Much like the Hindus in her home are. Look closely and you will see that abandoned home, those lost days of glory, that struggle to stay alive through collective memory. Look closely and you will hear the stories and the chants but you will not be able to experience them. That is what being uprooted and lost feels like.

The Goddess needs to get her home back.

Much like her devotees in her homeland in Kashmir need their homes back.

(The only efforts being made in this regard are the efforts of the Save Sharda Committee led by Mr. Ravindar Pandita and APMCC to begin the Sharda Peeth pilgrimage. In the current political situation, it is a tall task, but we can do our bit to ensure that the activists do not walk alone with their demands. )

The author had won a sponsorship from IndicToday in order to attend the National Seminar On Shakti Worship in India. This is an essay written based on her experience at the seminar.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Q. J., & Samad, A. (2015). Sarda Temple and the stone temples of Kashmir in perspective: A review note. Pakistan Heritage.

Ashraf, M. (2007). The Shrine of Sarada. Greater Kashmir.

Godbole, S. (n.d.). The Sharda temple of Kashmir. Retrieved from Kashmir.

Kaul, B. R. (n.d.). Abode of Goddess Sharda at Shardi.

Nazki, A. R. (2009). In search of roots. In S. S. Toshkhani, & K. Warikoo, Cultural Heritage of Kashmiri Pandits. Pentagon Press.

Rehman, F. u., Fida Gardazi, S. M., Iqbal, A., & Aziz, A. (2017). Peace and Economy beyond faith: A case study of Sharda temple. Pakistan Vision .

Singh, D. (2015). Reinventing Agency, Sacred Geography and Community Formation: The Case of Displaced Kashmiri Pandits in India. The Changing World Religion Map.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and Strategies . American Sociological Review, Vol 51.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.

4 Comments

The article itself is mesmerizing and gives a emotional aspect of how lost our duties to the temples are . Thank you for such a wonderful piece of info.

I feel the pain in the article. Thank you for taking part in this journey.

Every Hindu especially Kashmiri Pandits should join hands for demand to start pilgrimage to our sacred Teerath Maa Sharda

Sharada peeth in POK and Shankaracharya hill in srinagar both are equally ancient. Bothare 120 kM apart. Both temples are spiritually connected to each other. One is a shiva temple and one is a shakti temple. Both the temples were worshiped during Samrat Ashokaperiod. Both have same history. Both temples were renovated by the Great rulers of J&K Maharaja Gulabh singh. Adi Guru Shankaracharya visited both temples. Adi guru Shankaracharya mediated in shankaracharya hill in srinagar and then proceeded to Sharada peeth now in POK. Shankaracharya hill temple outer structure is intact but sarada peeth in now in ruins. Both temples were a great pilgrimage in kashmir for people of bharat.