Introduction: What Arises at the Last Moment?

A Lifetime’s Echo in the Moment of Death. The final breath carries the weight of a lifetime. What truly determines the last thought at the moment of death? Is it chance, some divine intervention, or is it something that has been building quietly across the years? The Bhagavad Gītā gives a powerful insight in Chapter 8, verse 6:

यं यं वापि स्मरन्भावं त्यजत्यन्ते कलेबरम् ।

तं तमेवैति कौन्तेय सदा तद्भावभावितः ॥ ८.६ ॥

yaṁ yaṁ vāpi smaranbhāvaṁ tyajatyantē kalēbaram |

taṁ tamēvaiti kauntēya sadā tadbhāvabhāvitaḥ || 8.6 ||

(“Whatever one remembers at the time of death, that alone one attains, being ever absorbed in that state of being.” )

This single line has stirred deep reflection for centuries. It does not suggest a sudden or last-minute decision. It points instead to something more enduring. The verse invites us to look not at death as a final accident, but as a culmination.

This raises a quiet but profound question. Is the final thought simply what the mind happens to recall in that moment, or is it the natural flowering of lifelong habits and inner patterns? When everything else begins to fade, what rises to the surface may not be what we wish, but what we have remembered most often and most deeply. And this memory is not just a recollection of facts. It is the subtle echo of what we held close, what we repeated, what we allowed to shape our inner being.

Chapter 8 of the Bhagavad Gītā is titled Akṣhar Brahma Yog (The Yog of the Imperishable.) It speaks about the soul’s journey beyond death, the ultimate truth that does not perish, and how conscious remembrance of that truth determines what we merge into. Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa does not speak in terms of fear or sudden salvation. He speaks of remembrance, of mental absorption, of the current that carries us through the threshold.

Both Vedanta and neuroscience point toward an unseen continuity. They suggest that the final moment is not random. It is the silent result of the life we have lived, the thoughts we have nurtured, and the memories we have given energy to.

What Are Smṛiti and Saṃskāra? Understanding the Inner Reservoir

In the Vedantic tradition, the mind is not just a place of thoughts. It is a field where impressions settle, grow roots, and quietly influence the course of life. Two subtle ideas help us understand this deeper landscape of the mind: smṛiti and saṃskāra.

Smṛiti is not just the ability to recall events. In its deeper sense, smṛiti is sacred memory. It is the lasting inner trace of what the mind has been drawn to again and again with emotion and attention. It is the echo of repeated remembrance. When someone says a prayer each morning, not mechanically but with feeling, that experience creates smṛiti. Over time, that remembrance stays alive even without effort. It may rise on its own in moments of silence or suffering. This is what makes smṛiti sacred. It is not just what we remember, but how deeply it has entered our being.

Saṃskāra refers to the subtle impressions left behind by thoughts, emotions, actions, and intentions. It is like the groove formed on a stone by dripping water. Every small repetition leaves a mark. For example, if a person often responds to stress with anger, that reaction becomes easier each time. Eventually, it becomes automatic. The same happens with joy, with fear, with devotion. These patterns settle into the subtle body, forming the foundation of personality and habit.

Yoga Sutra 1.43 of Patañjali says,

स्मृतिपरिशुद्धौ स्वरूपशून्येवार्थमात्रनिर्भासा निर्वीजा समाधिः

smṛti-pariśuddhau svarūpa-śūnyeva artha-mātra-nirbhāsā nirbījā samādhiḥ

(“When memory (smṛti) has been completely purified, the mind becomes devoid of its own projections, and only the object of meditation shines forth. This is known as nirbīja samādhi, or seedless absorption.”)

Thus “Yoga Sūtra 1.43” refers to the purity of memory leading to deep meditative absorption. This shows the spiritual importance of smṛiti. It is not just a support for memory, but a gateway into inner clarity.

Both smṛiti and saṃskāra accumulate silently. They build over time and form what can be called the inner reservoir of tendencies. This reservoir does not shout. It works quietly, deciding how we react, what we crave, what we fear, and even what we remember at the final moment. In Vedantic psychology, this entire field of subtle reaction and impression operates through the antaḥkaraṇa (the inner instrument composed of mind, intellect, ego, and memory) through which all experience is processed and stored. Understanding these forces allows us to live more consciously and plant the seeds for a peaceful mind when the body grows still.

The Inner Riverbed: Smṛiti and Saṃskāra in the Gītā’s View of Death

The Śhrīmad Bhagavad Gītā, particularly in Chapter 8, offers a profound psychological truth veiled in spiritual language: the final thought at the time of death is not a last-minute decision, but the natural culmination of one’s deepest saṃskāras those latent impressions that accumulate through repeated thoughts, emotions, choices, and actions. The mind, much like a riverbed carved over time, flows effortlessly along the channels most frequently shaped. In this way, the dying moment is not a surprise, but a reflection of the life lived.

In Vedantic thought, smṛiti is more than recollection. It is the inner echo of what the soul has truly received. It is the inner echo of what the soul has taken to heart, what has been repeated with emotional weight and conscious engagement. Each act of remembrance leaves an imprint, a saṃskāra, which forms a kind of inner residue. These saṃskāras accumulate quietly, becoming the substratum of one’s habits, preferences, emotional triggers, and even spiritual instincts. They shape the default response when the conscious mind weakens; such as during crisis, sleep, or death.

In this light, the Gītā’s teaching that “whatever one remembers at the time of death, that one attains” is not a mystical reward, but a law of inner continuity. What arises in the last moment is not randomly chosen, but is drawn from the reservoir of one’s most sustained inner tendencies. If the Divine, or the eternal Self, has been part of one’s daily remembrance, that presence will likely surface again at the threshold of death. If worldly cravings, anxieties, or egoic attachments have dominated, then those impressions will likely return.

The Gītā does not preach fear or fatalism through this insight. Rather, it encourages the seeker to treat every moment of life as sacred preparation. Every mantra repeated with attention, every moment of gratitude, every act of selfless service; all leave a trace. These traces refine one’s internal memory field, making divine remembrance more natural than effortful. Smṛiti becomes the companion of the sādhaka (seeker), and saṃskāra becomes the invisible sculptor of destiny.

Psychologically, this principle aligns with what is known in neuroscience as the reinforcement of neural pathways through repetition and emotional salience. Spiritually, it invites the seeker to live with vigilance, not out of anxiety, but with reverence. Each moment becomes a brushstroke painting the mural of the final moment. To die with Divine remembrance is not an accident; it is the result of a life where the sacred was remembered often enough to become one’s inner nature.

Ultimately, Smṛiti-Saṃskāra reveals that liberation is not secured in a single instant, but cultivated through the hidden architecture of memory shaped across years of conscious living. When life becomes the training ground for graceful dying, death itself becomes not an end but a culmination of steady remembrance; a gateway shaped not by chance, but by care.

The Science of Reinforced Memory: What Neuroscience Reveals

Modern neuroscience has revealed powerful truths about how memory is formed and sustained in the brain. These findings help us understand why the Bhagavad Gītā’s teaching about the last thought being shaped by lifelong remembrance is not just spiritual insight, but also scientific truth.

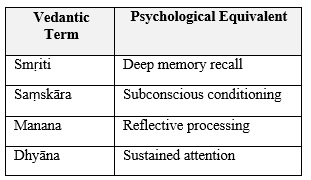

Before we explore what neuroscience says about how memory is shaped, here’s how some of these Vedantic ideas relate to common psychological terms we use today:

One of the key ideas in neuroscience is long-term potentiation. This is the process by which repeated signals between two neurons strengthen the connection between them. In simple terms, the more often we think a thought or repeat a behavior, the easier it becomes for our brain to repeat it again. The neural pathway becomes faster and stronger, like a well-trodden path in a forest. This is why habits are hard to break. It is not just mental. It is structural.

Another important principle is emotional salience. Our brain pays special attention to experiences that carry strong emotion. A joyful moment or a traumatic one gets recorded more deeply than something neutral. These emotionally charged memories often become part of our subconscious. They surface in dreams, sudden reactions, or times of stress. Even without conscious effort, the memory comes back because the emotional charge keeps it alive.

The default mode network is a set of brain regions that becomes active when we are not focused on the outside world. It often plays back our past, our worries, our sense of self. This quiet mental activity is shaped by our repeated thoughts, memories, and emotions. Over time, it builds the background of who we believe we are.

The Gītā says, “You become what you habitually think.” Neuroscience confirms this. Our brain adapts to what we give it regularly. Whether it is fear, longing, or devotion, repeated thoughts shape our mental grooves. They influence what arises in calm, in crisis, and at the very end. The final thought is not random. It is often what the brain and mind have rehearsed all along.

A Life Well-Lived Is the Best Preparation for Death

The Bhagavad Gītā does not use fear to guide the seeker. Its message is gentle yet powerful. It reminds us that death is not an interruption, but a continuation. The final moment is shaped not by panic or chance, but by the texture of our inner life. Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa encourages us to prepare, not by clinging to control, but by honoring each moment as a step toward that threshold.

In this view, every moment becomes a quiet opportunity. What am I remembering right now? Where is my mind resting when I am not trying to control it? These questions are not meant to burden us. They help us see that life is constantly offering us chances to plant something meaningful. Every act becomes a seed. Every act becomes a seed. Each thought becomes a sculpture. As the Bhagavad Gītā reminds us, from action arises the cycle of becoming (karma-saṁbhavaḥ), shaping what follows in this life and beyond. Over time, these inner shapes settle deeply. They rise again when everything else falls silent.

Simple practices can hold great power. Repeating a mantra every morning with care allows a name or sound to sink into the heart. Taking a few moments before sleep to recall something you are grateful for reshapes the mental field. A brief pause before reacting in anger plants the seed of awareness. These are not grand acts. They are quiet impressions that, repeated over years, become part of who we are.

We often think that divine remembrance at death requires effort in the final hour. But the Gītā’s teaching is clear. Dying with sacred memory is the natural fruit of having lived with it. If remembrance was your steady companion in ordinary life, it will not abandon you when the body prepares to rest. A life lived with conscious memory is the best preparation for a peaceful transition. It is not about holding on. It is about becoming something gently, over time, with trust.

Real-Life Reflections: Saints, Seekers, and Final Moments

Stories of final moments often reveal more than philosophies ever can. They show how the life one has lived continues to speak even in silence. The last breath does not invent something new. It echoes what the heart has held closely for years.

There was a revered monk in a quiet āśhram in Rishikesh, known for his lifelong devotion to his Iṣhṭa-devatā, the Divine Mother. Every morning and evening, he offered a small flower and chanted her name with great gentleness. In his final days, when his body was growing weak and speech was fading, those around him heard just one word repeated in a whisper: “Mā.” That name had entered his breath, his heartbeat, and his memory. It did not need effort in the end. It simply rose because it had become part of him.

In another account, a man in his later years was overwhelmed by regrets. He had lost relationships through anger, missed chances through fear, and carried guilt he never shared. In his final hours, his family sat beside him, but he turned away. He kept repeating old worries, names of people he never made peace with, and moments he couldn’t let go of. No comfort seemed to reach him. His mind had practiced this kind of memory for years, and it returned when he could no longer resist it.

In her final days, resting in a quiet room by the window, a woman with no formal spiritual practice asked her nurse to keep reading letters from her grandchildren. She held them like treasures, asking for the same ones again and again. As her final moment approached, her face grew calm. A soft smile appeared, and she whispered the names of those she had loved the most. Though she had no mantra or ritual, her heart had been shaped by love. That gentle affection had become her memory.

These stories remind us that what we remember at the end is not what we want to remember. It is what we have remembered the most. The final moment reflects the shape of a life, not just its conclusion. The inner world, built quietly over time, becomes the voice that speaks when all else falls away.

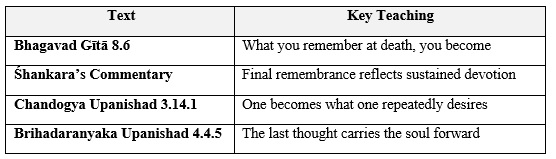

Scriptural Support and Commentary Voices

The insight that the final thought at death is shaped by a life of remembrance is not isolated to one verse of the Gītā. It is a theme that runs through many layers of Indian wisdom texts. The Bhagavad Gītā, the Upanishads, and the commentaries of great thinkers like Śhankara all echo this quiet truth.

In Chapter 8, verse 5 of Bhagavad Gītā, Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa says,

अन्तकाले च मामेव स्मरन्मुक्त्वा कलेबरम् ।

यः प्रयाति स मद्भावं याति नास्त्यत्र संशयः ॥ ८.५ ॥

antakālē ca māmēva smaranmuktvā kalēbaram |

yaḥ prayāti sa madbhāvaṁ yāti nāstyatra saṁśayaḥ || 8.5 ||

(“One who remembers Me alone at the time of death, letting go of the body, attains My state of being without doubt.”)

We saw earlier this is followed by verse 6, which deepens the idea: “Whatever one remembers at the time of death, that alone one attains, being always absorbed in that.” These two verses together make it clear that death does not decide, but reflects. The state of mind at the end is a reflection of what one has been devoted to through life.

Śhankarāchārya, in his commentary on these verses, explains that remembrance at the moment of death is not something that can be fabricated suddenly. He says it is possible only for the one who has trained their memory through repeated devotion and clarity of purpose. In his view, smṛiti at death is a result of mental discipline, not chance. It is the fruit of a life of mindful presence.

The Chandogya Upanishad also supports this idea. In 3.14.1, it states:

स य एषोऽणिमैतमात्म्यमिदं सर्वं तत्त्वमसि श्वेतकेतो । तत्त्वमसि इति । स आत्मा तत्त्वमसि श्वेतकेतो ॥

स क्रतुं कुर्वीत । पुरुषो हि क्रतुं कुरुते । स यथाक्रतुरस्मिँल्लोके पुरुषो भवति तत एतः प्रेत्य भवति सः क्रतुः ।

sa ya eṣo’ṇimaitam ātmyaṁ idaṁ sarvaṁ, tat tvam asi śvetaketo, tat tvam asi iti. sa ātmā, tat tvam asi śvetaketo.

sa kratuṁ kurvīta. puruṣo hi kratuṁ kurute, sa yathākratur asmiṁl loke puruṣo bhavati, tathetaḥ pretya bhavati saḥ kratuḥ.

(“This subtle essence is the Self of all. That is the truth. That is the Self. You are That, O Śvetaketu.”)

A person should form a firm resolve (kratu) because a person is made of their resolve. As is their resolve in this life, so they become after death. This resolve shapes their actions, and through those actions, they become what they are.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad also affirms that the thought held at the moment of leaving the body leads the soul to the next realm.

बृहदारण्यकोपनिषद् ४.४.५

यथाकालं चायं पुरुषो मृतः स प्रेत्य यथाकृतं यथाचरितं तदभिसंपद्य स्वस्त्यात्मानं अभ्यनन्दति ।

yathā kālaṁ cāyaṁ puruṣo mṛtaḥ sa pretya yathākṛtaṁ yathācaritaṁ tad abhisampadya svasty ātmānaṁ abhyanandati.

(“As a man acts and as he conducts himself, so he becomes. Upon death, he goes to the next world according to his deeds and the thoughts he has formed. Reaching that result, he rejoices in the Self, if he has lived wisely.”)

These scriptures together form a quiet chorus. They tell us that inner practice matters. Remembrance is not a last-minute act. It is a long habit of the heart.

Scriptures That Echo This Insight

Living Smṛiti: Daily Practices to Shape Inner Memory

Smṛiti is not only something that happens to us. It is something we can gently shape. Just as daily habits leave marks on the body, repeated moments of attention leave impressions on the mind. The Bhagavad Gītā invites us to live in such a way that remembrance becomes part of who we are, not just something we do. When remembrance becomes natural, it carries us quietly, even when we are no longer trying.

One simple way to begin is with morning smṛiti. Before the day begins, take a few still moments to invoke the sacred. This could be through a short prayer, a silent name, or even just sitting with the thought of the divine. This early remembrance sets the tone for the rest of the day. It gives the mind a quiet thread to return to.

Journaling also helps strengthen sacred memory. Writing down something you feel grateful for, or recording the name of your chosen deity or an uplifting verse, helps to anchor the heart. These small acts deepen emotional memory and bring inner warmth.

The practice of svādhyāya, or daily study of sacred texts, is another way to guide smṛiti. Reading even a few lines of the Gītā or the Upanishads reminds the mind of higher truths. Over time, these teachings settle deep and begin to speak from within.

In moments of stress, pausing for a mantra or a breath of reflection allows a different kind of memory to rise. These small pauses break the usual grooves of reaction and give space for clarity.

As the day closes, ask gently: What memory did I strengthen today? Was it worry or trust? Craving or peace? This question, asked without judgment, helps bring awareness into daily life. Over time, such questions become quiet tools of transformation.

Meditation and Remembrance: The Role of Dhyāna Yog

In Chapter 8 of the Śhrīmad Bhagavad Gītā, meditation is revealed as a path of inner integration rather than an isolated act. Dhyāna Yog, the Yog of Meditation, brings together thought, emotion, breath, and awareness into a state of quiet alignment with the Divine. It is not bound to posture or place. It is a steady shaping of the mind to return, again and again, to what is real.

Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa describes the yogi who, at the time of death, directs the prāṇa between the eyebrows with a focused mind absorbed in Him. This is not a sudden feat but the natural flowering of long preparation. The Gītā shows that meditation is not just something we practice occasionally, but a way of being where the mind no longer drifts aimlessly and the sense of self begins to settle into something timeless.

At the heart of this practice lies remembrance (smaraṇa). When the mind is trained to rest in sacred memory, it begins to return there not from effort, but from love. This remembrance becomes a current that flows beneath all activity, carrying the practitioner back to the Divine again and again.

This path is held together by several inner strengths. Concentration (dhāraṇā) gives the mind steadiness. Devotion (bhakti) fills the heart with warmth and surrender. Discrimination (viveka) guides attention toward what is lasting. Discipline (abhyāsa) brings constancy through the changing tides of experience. Without these, meditation remains scattered. With them, it becomes whole.

As Dhyāna Yog deepens, even the sense of “I am meditating” begins to dissolve. The effort to remember gives way to the natural presence of awareness. What began as seeking settles into resting. The Gītā calls this the sacred maturity of a mind aligned with the imperishable. It is not only the ground for peaceful living, but the quiet preparation for a fearless end.

Deepening Insight: Nādi-Viveka and the Subtle Path of Departure

In Chapter 8 of the Śhrīmad Bhagavad Gītā, Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa describes how a yogi, at the moment of death, directs the life-force (prāṇa) between the eyebrows, implying an advanced mastery over the inner energy system. This cryptic yet powerful reference touches the heart of nādi-viveka, or the subtle discernment and mastery of the body’s prāṇic channels. In the yogic tradition, nāḍīs are not physical nerves but subtle channels through which prāṇa; the vital life energy flows. Among the 72,000 nāḍīs described in yogic texts, the suṣhumnā nāḍī, which flows through the central axis of the spine, is the most sacred, and is associated with spiritual ascent and liberation.

Nādi-viveka refers not merely to intellectual knowledge about these channels, but to the lived sensitivity and inner clarity to feel, direct, and purify them. This discernment arises from practices such as prāṇāyāma, bandhas, and meditative absorption. As these practices mature, the yogi begins to sense which channels are active, which are blocked, and how to harmonize the opposing energies of iḍā (lunar, cooling) and piṅgalā (solar, heating) so that they merge into the suṣhumnā, allowing a free, unbroken current of awareness to ascend.

In the Gītā’s teaching, the ability to guide the prāṇa upward at the time of death is not a symbolic idea; it is a practical, energetic reality. If the soul exits through the lower gateways, it is drawn into realms associated with instinct, fear, and worldly longing. But when consciousness rises through the brāhmarandhra (the aperture at the crown of the head) via the suṣhumnā, it is released into the vast field of transcendence. This is not accidental; it is the fruit of lifelong preparation, of aligning the body, breath, and mind in remembrance of the imperishable.

Such discernment also influences how one lives. A person with nādi-viveka becomes attuned to the flow of subtle energy in daily actions; what uplifts the current and what scatters it. Idle talk, restless activity, or indulgent habits cause dissipation. In contrast, silence, prayer, breath awareness, and focused study strengthen the upward pull. Over time, even before death, the practitioner begins to live from a higher center. The heart feels lighter, the mind clearer, and decisions begin to reflect the rhythm of a more refined inner intelligence.

Nādi-viveka thus becomes a sacred link between spiritual philosophy and embodied wisdom. It teaches that liberation is not only a matter of belief or intention, but of how energy flows within. The inner pathways must be cleared, balanced, and illumined for the soul’s upward journey to unfold. In Gītā’s vision, the soul does not rise by force or escape but by tuning its entire being into the natural current of transcendence and this tuning is the essence of nādi-viveka.

Conclusion: Memory as Destiny, Remembrance as Liberation

Smṛiti and saṃskāra offer us a deep meeting point between Vedanta, psychology, and personal experience. They remind us that the mind is not just a container of thoughts. It is a field that remembers, absorbs, and quietly shapes what we become. The Bhagavad Gītā teaches that the final moment is not something to fear. It is not a surprise. It is the natural result of what we have carried within us all along.

Modern psychology confirms that repeated thoughts and emotions create lasting patterns. These patterns become automatic responses, shaping how we react, what we hold close, and what arises in silence. Vedanta calls these patterns saṃskāras. And it tells us that they do not just shape our life. They shape our departure.

Memory is not just a storehouse. It is an inner sculptor. Each day offers a chance to turn remembrance into a living presence. With every sacred thought we repeat, every small act of attention, we carve new impressions. These become part of us. And when the time comes to let go, they are what rise.

What we water grows. What we remember, we become. And what we become, we carry into the next great transition. In this way, remembrance becomes not just a practice, but a quiet form of freedom.

Five (05) Questions to Reflect on Smṛiti in Your Life

- What thoughts recur in your mind each day?

- What names or ideas do you remember before sleeping?

- In times of stress, what do you instinctively turn to?

- What memories make you feel most alive?

- If your life ended today, what would your final thought likely be?

Key Terms

Here are the key terms glossary in alphabetical order

- Abhyāsa: Steady inner discipline developed through repetition and sincere effort; supports remembrance and prepares the mind for stillness

- Antaḥkaraṇa: The inner instrument of perception and experience, made up of mind (manas), intellect (buddhi), ego (ahaṅkāra), and memory (citta or smṛiti). It is through the antaḥkaraṇa that impressions (saṃskāras) are formed, stored, and recalled. It serves as the subtle seat where thought, feeling, and identity are processed and shaped.

- Bhakti: Inner devotion and loving surrender to the Divine; the heart’s natural movement toward sacred presence

- Dhāraṇā: Concentrated attention; the quiet training of the mind to stay with one object or presence without drifting

- Dhyāna Yog: The discipline of meditation as taught in the Bhagavad Gītā; not just a practice, but a way of being where thought, breath, and awareness rest in the sacred

- Karma-saṁbhavaḥ: A phrase from the Bhagavad Gītā (3.14) meaning “born of action.” It reflects the idea that all cycles of life, experience, and consequence arise from karma—conscious action. It emphasizes that each act leaves an imprint and contributes to the unfolding of destiny.

- Prāṇa: The subtle life-force or vital energy that sustains the body and mind; directed upward in spiritual practices and at the time of death

- Saṃskāra: Subtle impressions formed by repeated thoughts, emotions, and actions; the unseen patterns that shape inner tendencies and final states of mind

- Smaraṇa: Inner remembrance of the Divine; not merely recall, but a living connection that becomes the natural resting place of the mind

- Smṛiti: Sacred memory shaped by emotional weight and sustained reflection; becomes the echo that rises in silence, especially at life’s end

- Suṣhumnā Nāḍī: The central subtle channel through which prāṇa ascends in deep spiritual practice; associated with clarity, awakening, and the upward path of liberation

- Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa: The guide and teacher in the Bhagavad Gītā who reveals the inner laws of consciousness, remembrance, and the journey of the soul

- Viveka: Inner discernment that allows one to recognize what is lasting and what is passing; the clarity to choose remembrance over distraction

- Yog: The inner union of the individual soul with the Supreme; a path of integration, preparation, and conscious living through thought, action, and remembrance

Further Reading

For deeper insight into the themes explored in “Smṛiti-Saṃskāra: How Memory Shapes the Final Moment”

1. Vivekachudamani – Adi Shankaracharya

A brilliant and poetic exposition of discrimination, remembrance, and liberation. This text explores how viveka (discernment), smaraṇa (remembrance), and detachment lead to freedom. It complements the article’s message that the soul rises through what it has lived, not what it hopes for.

2. Bhagavad Gītā – Home Study Course by Swami Dayananda Saraswati

A structured and profound exploration of the Gītā rooted in traditional Advaita Vedanta. Swami Dayananda’s detailed guidance on karma, remembrance, and the role of prāṇa at death provides essential background to understanding smṛti and saṃskāra from a seeker’s perspective.

3. Bhagavad Gītā – Translation and Commentary by Swami Chinmayananda

This commentary provides deep clarity on Chapter 8, especially verses 5 to 10. It explores how remembrance at the time of death is a continuation of conscious living and connects smṛti to the daily choices we make in thought and action.

4. Yoga Sutras of Patanjali – Translation by Swami Satchidananda

The sutras speak directly of smṛti, abhyāsa, and the purification of mental impressions. It offers a foundation for understanding how concentration, remembrance, and discipline clear the path for inner stillness and final clarity.

5. Meditation and Mantras – Swami Vishnudevananda

An accessible guide to the role of mantra and remembrance in everyday life. It helps explain how sustained repetition shapes inner impressions and prepares the mind for deep absorption and final stillness.

6. The Upanishads – Translation by Eknath Easwaran

Especially helpful are passages from the Brihadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanishads, which speak of last thoughts, subtle identity, and the journey of the soul beyond the body. These texts give deep background to the ideas of saṃskāra and upward movement of prāṇa.

Note on Sources: This article draws from key teachings across Chapter 8 (Akṣhar Brahma Yog) of the Bhagavad Gītā, with special focus on verses 8.5 to 8.10. These verses explore the significance of remembrance at the time of death, the role of saṃskāra in shaping one’s final state, and the inward preparation required to direct the life-force toward the Supreme. The insights are situated within the broader Vedantic framework of the Prasthāna-Traya; the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gītā, and the Brahma Sutras which together offer a comprehensive vision of the Self, subtle memory, and liberation.

The reflections are inspired by the teachings of Adi Shankaracharya, Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Swami Chinmayananda, Swami Satchidananda, and others who have illuminated the depth of smṛiti, saṃskāra, dhyāna yog, and the subtle movements of prāṇa. While the tone of this article is reflective and accessible, the central ideas remain rooted in traditional Sanskrit sources and uphold the spiritual clarity offered by classical commentaries and lived practice.

Feature Image Credit: wikipedia.org

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.