When the enemy was at the fort gates, when rations ran out, and when defeat was certain, Rajput kingdoms, especially in northwestern India followed a code of honour that inspires awe and dread to this day. All the women within the fort led by queens dressed in their wedding fineries and jewellery, along with children would step into a large fire and turn to ashes in a ceremony called Jauhar before the enemy set upon them.

While the women burned, the Rajput men performed the Shaka or the last fight from which there was no return. The fort gates would be thrown open and the men, dressed in kesariya or saffron, the Hindu colour of renunciation, with tulsi leaves in their mouths would charge into the enemy with the aim of killing as many as possible before breathing their last.

Rajput women who performed Jauhar were regarded as brave pativratas, or exemplars of such deep devotion for their husbands that they would prefer to join them in their next birth rather than live a life of separation and dishonour.

The men who rode out to perform Shaka (or Saka) were also highly respected for performing the most fearsome of sacrifices. It was in keeping with the courage and integrity that Rajputs were known for.

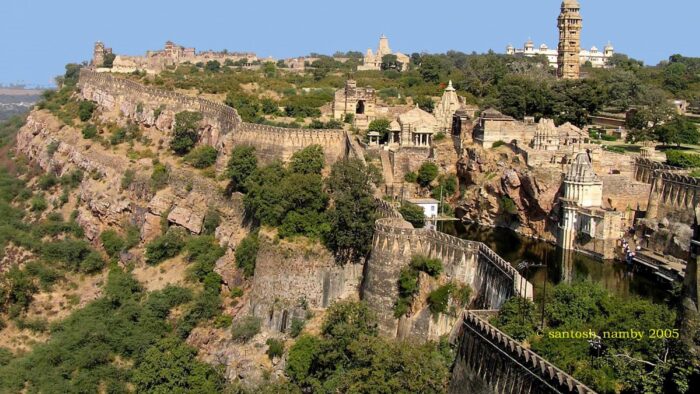

The Jauhars of Chittorgarh

The land of Chittorgarh in the Mewar region located in the state currently known as Rajasthan has witnessed at least three instances of Jauhar in 1303, 1535 and 1568. It is the first place that comes to mind when talking of the ritual and Rani Padmini is associated with its most famous Jauhar.

It is believed that the Muslim despot Allauddin Khalji was so besotted with the beauty of the Rani for which she was acclaimed throughout the land that he decided to capture the Fort of Chittor. The Rani, however, followed the code of honour and did not fall into his hands.

While many historians believe that the story of Padmini as told in the ballad Padmawat is a figment of the imagination, there is literary evidence that a Jauhar took place when Khalji mounted his attack on Chittor in 1303. Khalji’s rapacious attacks led to many such immolations of Rajput queens which were recorded by historians in his time and later.

The second instance of Jauhar in Chittor was during the attack of another Muslim ruler Bahadur Shah of Gujarat when Rani Karnavati was ruling in the name of her son. Rana Sanga, her husband had been defeated by Mughal king Babur in the Battle of Khanua and had later died of his wounds.

It must be noted that the Rani had not committed Sati (the voluntary practice of self-immolation of a wife on the death of her husband) but chosen to manage the affairs of her husband’s kingdom. Unfortunately, she could not ward off the onslaught of the latest invader Bahadur Shah and decided it was time for the Jauhar-Shaka ritual.

Locking herself in a vault with 13,000 other women and children, she ordered for gunpowder to be used to create the agni needed for burning. Pannadai, the Rani’s maid was entrusted with the princes in order to continue the bloodline and she managed to take them away to safety. The men of the fort wore saffron and poured out to fight to the finish.

However, at a later point in time, the kingdom of Mewar including the fort of Chittor was restored to the Sisodiya Rajputs and was ruled by Vikramaditya and Udai Singh II one after the other – both of them being the princes who had been whisked away to safety during the siege and Jauhar-Shaka of 1535.

The ignominy of precipitating the third and final documented instance of Jauhar-Shaka in Chittor Fort can be attributed to Mughal king Akbar. At the helm of Mewar was Rana Udai Singh II, the fourth son of Rana Sanga and Rani Karnavati. Many Rajput rulers submitted to Akbar but Mewar refused to bend. Rana Udai Singh II had decided to strategically set up his temporary capital in Gogunda, leaving Chittor in the hands of his loyal chieftains Rao Jaimal and Patta.

Akbar’s siege of Chittor in 1567 was a brutal one. He employed over 5,000 expert builders, carpenters and stonemasons to dig mines and sap the walls of the fort but hundreds of them died due to the continual firing by Rajputs. Enraged by this, Akbar ordered a general massacre following four months of siege.

“Rising pillars of smoke soon signalled the rite of Jauhar as the Rajputs killed their families and prepared to die in a supreme sacrifice,” says John F Richards in “The Mughal Empire”.

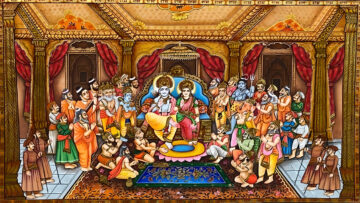

The Jauhar of Rajput women at Chittorgarh as shown in Akbarnama, V&A Museum, Public Domain.

According to historian Satish Chandra, in addition to the men who came out of the fort to die fighting, there were 8,000 more Rajput men inside the fort who died defending their temple. About 30,000 people were killed, including peasants who were aiding the Rajput soldiers.

In his biography of Akbar, Abul Fazal wrote about the Chittor massacre:

“On this memorable day although there was not in the place a house or street or passage of any kind that did not exhibit heaps of slaughtered bodies, there were three points in particular at which the number of slain were surprisingly great; one of these was at the palace of the Rana, into which the Rajputs had thrown themselves in considerable numbers; from whence they successively sallied upon the imperialists in small parties, of two and three together, until the whole had nobly perished sword in hand. The other was the temple of Mahadeo, their principal place of worship, where another considerable body of the besieged gave themselves up to the sword. Thirdly, was the gate of Rampurah, where these devoted men gave their bodies to the winds in appalling numbers.”

Other documented instances of Jauhar-Shaka

Jaisalmer in Rajasthan was the site of two horrific instances of Jauhar. The first was in 1298 when Allauddin Khalji’s troops attacked the Bhatis to avenge their raids on a caravan, which was transporting valuables. 24,000 women voluntarily gave themselves up to fire and 3,800 Bhati men committed Shaka.

The fort was abandoned for some time but the surviving Bhatis reoccupied it. About a hundred years later, when one of the Jaisalmer princes stole a steed from Sultan Firoze Shah Tughlaq, another tyrant who ruled from Delhi, the latter mounted an attack on the desert fort and the entire saga was repeated. This time 16,000 women immolated themselves to avoid dishonour.

Further episodes of Jauhar-Shaka were recorded in Ranthambhore in 1301 (during Allauddin Khalji’s attack on the kingdom of Hammiradeva); Chanderi in 1528 (during Babur’s attack on the kingdom of Medini Rao); Raisen in 1532 (during Bahadur Shah’s attack on the kingdom of Silhadi); and again in 1543 (during Sher Shah’s attack on the kingdom of Puran Malla).

The infamous Aurangzeb’s assault on the Bundelas in 1634 also led to a Jauhar in which those ladies who could not complete the ritual were dragged into the Mughal harem while two princes were converted to Islam and the third who refused to convert was put to death.

Even in southern India, there is one documented incident of Jauhar in 1327 when Muhammad bin Tughlaq attacked the kingdom of Kampili, which was established by an erstwhile Hoysala commander Singeya Nayaka III.

The women consigned themselves to flames and the ruling king’s head was sent to Tughlaq by his general as a sign of victory. The Vijayanagara Empire came up on the ruins of this very Kampili kingdom.

Hammira Mahakavya, a Sanskrit epic written in the 15th century gives some detail about Alauddin Khalji’s massive attack on Chahamana king Hammira of Ranthambhore. It describes how Khalji made Hammira’s brother defect to his side, how he demanded a heavy tribute, and the hand of Hammira’s daughter. As the granary ran out of food grains, Hammira’s queens and even his dejected daughter ask him to give her up to the enemy and save the fort.

The epic portrays Hammira as saying that giving his daughter away to an unclean mlechcha was as loathsome as prolonging existence by living on his own flesh. A Jauhar is conducted by all the womenfolk and Hammira is described as throwing himself on the Muslim army. Amir Khushro has also written in Persian about this Jauhar in Ranthambhore.

One Rajput Vaghela queen Kamala Devi who could not commit Jauhar fell into the hands of Allauddin Khalji. She was captured and married forcibly to Khalji. When her daughter, the ravishingly beautiful Deval Devi grew older, she was married to Khalji’s son Khizr Khan and one by one, two brothers of Khizr Khan captured and married Deval Devi after a series of brutal wars.

Flourishing slave markets in the Muslim world

Ostensibly, the main reason for Jauhar-Shaka was to avoid rape, dishonour and enslavement, perhaps even necrophilia by the invading Muslim armies. The horrific accounts of the Arab invasion of Sindh in the eighth century might have been well-known.

The Arabs were the first invaders of India who removed large numbers of its native inhabitants as enslaved captives, according to André Wink in “Al Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic World”. Referring to the Sind invasion, he also says:

“…invariably numerous women and children were enslaved. The sources insist that now, in dutiful conformity to religious law, ‘the one-fifth of the slaves and spoils’ were set apart for the caliph’s treasury and despatched to Iraq and Syria. The remainder was scattered among the army of Islam. At Rūr, a random 60,000 captives were reduced to slavery. At Brahamanabad 30,000 slaves were allegedly taken. At Multan 6,000. Slave raids continued to be made throughout the late Umayyad period in Sindh, but also much further into Hind, as far as Ujjain and Malwa. The Abbasid governors raided Punjab, where many prisoners and slaves were taken.”

In the 11th century, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni made a series of plundering attacks on India in which there was mass slaughter and destruction of temples as well as enslavement. Chronicler al Utbi said (about Mahmud’s attack on Raja Jaipal’s kingdom):

“God bestowed upon his friends such amount of booty as was beyond all bounds and all calculation, including five hundred thousand slaves, men and women.” Among the captives were Raja Jaipal, his children, grandchildren, nephews and other relatives who were all driven to the slave markets of Ghazni for selling.

Further, with reference to Mahmud’s attack of Ninduna (Punjab) in 1014, al-Utbi said: “Slaves were so plentiful that they became very cheap; men of respectability in their native land were degraded by becoming slaves of common shopkeepers (in Ghazni).”

After Mahmud’s assault on Thanesar (Haryana), the Muslim army ‘brought 200,000 captives so that the capital appeared like an Indian city; every soldier of the army had several slaves and slave girls,’ testifies chronicler Ferishtah (“qarib do sit hazaar banda”).

The gruesome saga of slave-capturing continued throughout the Muslim rule in India, including the period of Mughals, as recorded by the Muslim historians themselves. Sometimes, the numbers of prisoners were mentioned, at other times they were not, but many sources record with glee that slaves were becoming cheap and plentiful.

If Allauddin Khalji had 50,000 slave boys in his service, then Firoz Shah Tughlaq was noted to have 180,000 of them. Amir Khushrau, the Persian composer said the Turks could seize, buy or sell a Hindu whenever they pleased. Female slaves were seen as a means of increasing the Muslim population of the world. Fresh batches of slaves kept arriving in the slave markets of Delhi.

There were trading communities like Ghakkars in Punjab, which specialized in bartering slaves from India in exchange for horses from Central Asia. Hindu slaves were transported in thousands to the slave markets in Central Asia via the Hindukush (meaning ‘Hindu-slayer’ in Persian) mountains in the Himalayas; many perished due to the intense cold, which gave the name to the mountains.

According to Scott C. Levi, Hindus were especially in demand in the early modern Central Asian slave markets because of their identification in Muslim societies as kafirs or non-believers. He also notes that skilled artisans and attractive females were much sought after:

“Demand was especially high for skilled slaves, and India’s comparatively larger and more advanced textile industry and agricultural production, and its magnificent imperial architecture, demonstrated to its neighbours that skilled labour was abundant in the subcontinent. This accounted for the common practice of rival political powers enslaving and relocating large numbers of artisans following successful invasions. For example, during Timur’s late fourteenth-century sack of Delhi, several thousand skilled artisans were enslaved and taken to Central Asia. Timur presented many of these slaves to his subordinate elite, although he reserved the masons for use in the construction of the Bibi Khanum mosque, located in his flourishing capital of Samarqand. It is perhaps not surprising that attractive, young female slaves commonly demanded an even higher market price than those skilled at construction engineering.”

— Scott C. Levi, Hindus beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade

Akbar decreed twice that enslavement of women and children during wars should be stopped. It was not taken seriously even by his own generals and subsidiary rulers; besides Akbar himself disregarded ethics when he ordered the siege of Chittor and called for no one to be spared, not even women. During his reign, children were kidnapped and traded, a practice, which his son Jahangir also mentioned in his memoir.

Foreign travelers such as Manrique and Bernier have noted that during the reign of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, peasants along with their wives and children were carried away by tax collectors if they could not pay their dues, and were sold in various markets and fairs.

India was a rich land in every sense of the word – in material riches, in human resources, in artistic talent – but what completed the picture of irresistibility to the Muslim invaders was that it was a land of kafirs. There was much Islamic virtue to be gained by converting or killing the Hindu “idol worshippers” of India.

Rajput women set the standards of valour

Given that the enslavement of human beings and their buying and selling became a thriving business in Muslim-ruled India, it should not at all come as a surprise that so many Rajput clans resorted to Jauhar-Shaka when defeat was unavoidable. Since cremation is the sacred Hindu rite for releasing the Atman, it made sense that the women chose fire over poison or any other means of dying.

Many social studies researchers have looked at Jauhar as a practice that objectified Hindu women and rendered them helpless victims of a patriarchal society. Such a perspective shows ignorance of not only Hinduism, but the conditions that existed in Indian society when it was overrun by medieval Muslim rulers steeped in religious intolerance and violent ideologies.

It also overlooks the fact that the Rajput women of the time themselves expected their men to conform to norms of courage and honour. Traditionally, it was the queen who handed the sword to her king before every battle.

Rajput folklore includes numerous tales of Ranis who did not take kindly to any hint of cowardice in their menfolk and shamed them into doing the right thing. This is exactly why the men who set out on Shaka were forbidden from returning alive.

Take the story of Hadi Rani, the Rajput princess who compelled her newly-married husband Rao Ratan Singh to heed the call of his father, the king of Mewar to stop the march of Aurangzeb’s army even though he was reluctant to leave her side. When Rao ji sent back a sentry to get a memento from his wife to carry to the battle, she cut off her head, which was duly delivered to her husband. Her message was clear – nothing was to come in the way of a Kshatriya’s Dharma. Rao ji fought and won the battle; however, according to legend, he killed himself in order to unite with his wife in death.

There is also the example of Rani Durgavati, the Queen of the Gonds who effectively administered the kingdom for 15 years after her husband died. She often fought battles herself and even defeated the Mughals in some of them. In the last battle she fought with the forces of Akbar, when defeat was imminent after severe wounds, she stabbed herself rather than fall into the hands of the Mughal army.

Conclusion

Eventually, only a small section of Rajputs such as the Sisodiyas was able to hold out against the Muslim despots; most Rajput kings formed alliances with the Muslims. The Marathas emerged as a dominant power eclipsing the waning Mughals and Rajputs. Later, the Rajputs formed partnerships with the East India Company and in independent India, their kingdoms were integrated into the state of Rajasthan.

Some historians have held that the lack of effective war strategies, disunity amongst clans and an extreme sense of honour and ethics prevented the Rajputs from successfully thwarting the invaders that poured into India.

According to Wilhelm von Pochhammer:

“They let the fleeing enemy escape without molestation, they set free the enemy leaders taken prisoner without demanding equal treatment for their own captured leaders, on the wrong assumption that the semi-barbaric steppe people would reciprocate such refined rules of war. They did not understand that it was not a knights’ tournament they were engaged in, but that they were locked in a naked and hard struggle for survival, as the invaders not only wanted to destroy Hindu culture but also send the bearers of the culture to hell. Even the Jauhar, the voluntary immolation of all women and the last sally of soldiers determined to fight till the last breath, were from the point of view of bravery, no doubt very exalted acts but from the political point of view, it was just the goal the enemy had set for himself, namely that of destroying the largest number of non-believers.”

The days of Jauhar-Shaka are gone. The bard traditions are dead. The forts and palaces of Rajasthan are thronged by hordes of selfie-taking tourists, while moviemakers are producing their own glamorized versions of histories. Academic papers on gender, violence, sexuality, and freedom have included Jauhar in the list of perverse practices of a medieval era.

But, once upon a time, a ballad immortalized a queen Samyukta (also known as Sanyogita) who wrote to her king Prithviraj Chauhan:

“Sun of the Chauhans…Is life immortal? Therefore draw your sword, smite down the foes of Hindustan; think not of self – the garment of this life is frayed and worn. Think not of me – we two shall be one. Hereafter and forever – go, my King!”

Bibliography:

- Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present, Kaushik Roy (2012) Cambridge University Press,

- The Mughals of India, Harbans Mukhia, Blackwell Publishing (2004)

- Indian Castles 1206–1526: The Rise and Fall of the Delhi Sultanate, Konstantin S Nossov, Konstantin Nossov, Osprey Publishing

- Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives, Lindsey Harlan (1992), University of California Press

- Women of India – Their Status since the Vedic Times, Arun R Kumbhare (2009), iUniverse Inc.

- Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy – The ethnohistory of the military labour market in Hindustan – 1450-1850, Dirk H A Kolff (1990), Cambridge University Press

- The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799): A Comprehensive Chronology of the Spread of Islam in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, Everett Jenkins, Jr. (2000), McFarland.

- Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part – II, Satish Chandra (2005), Har-Anand Publications.

- The Ethics of Suicide: Historical Sources, Margaret Pabst Battin (2015), Oxford University Press

- A Comprehensive History of Medieval India, PN Chopra, BN Puri, MN Das (2003), Sterling Publishers

- Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material. S.R. Sharma (1999), Atlantic Publishers

- Head and Heart: Valour and Self-Sacrifice in the Art of India, Mary Storm (2015), Taylor & Francis.

- Epic and Counter-Epic in Medieval India, Aziz Ahmad (1963), Journal of the American Oriental Society

- Rajasthan: Land of Kings, Roloff Beny and Sylvia Matheson (1984), Frederic Muller Ltd

- Islamic Jihad: A Legacy of Forced Conversion, Imperialism, and Slavery, M.A. Khan (2009)

- Al-Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World, vol. 1, Andre Wink (1991), Brill Academic (Leiden)

- Hindus beyond the Hindu Kush: Indians in the Central Asian Slave Trade, Scott C. Levi (2002), Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Third Series, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Nov. 2002), Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- India’s Road to Nationhood: A Political History of the Subcontinent, Wilhelm von Pochhammer (1981), Allied

- Women in India: A Social and Cultural History, Sita Anantha Raman (2009), Praeger

Featured Image: Chittorgarh Fort. Courtesy: Santosh Namby

This article was first published on India Facts.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. Indic Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.