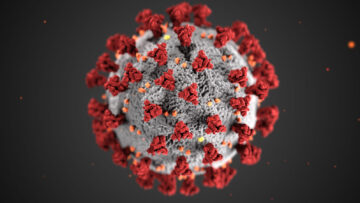

What does inner dimension mean and how does it relate to what mankind is witnessing in uncertain times like now?

Until the pandemic broke, we were constantly engaged with the world outside of us. For a fast-paced world such as ours, there was literally no scope to ‘STOP and LOOK’ within. We were desperately fixated on the extraneous marathon of life to the extent that we completely ignored the guiding light well within the confines of our own self.

We hear and read a lot of affirmations, quotes, thoughts about going within, but what does it actually mean. Let me begin with a simple analogy of the human body and mind with that of hardware and software of a computer, we are born with a physical body, which forms the hardware component.

The hardware is just the gross form that we see externally, this starts functioning based on the type and number of software installed. After our birth we are given a name which becomes our first identity, slowly we start recognizing and identifying ourselves with the external world, our family members, the place where we live, and then we gradually learn many different things as we grow older.

Mind imprints itself with various kinds of anubhavas (experiences or inputs) which forms the very basis of our samskāras (mental impressions), codes, or programs. These samskāras develop into our svabhāva (nature) which forms the most important component of the software which governs our hardware. We are born with a certain svabhāva – inherent nature – which forms our core personality. A certain portion of it is genetically inherited and a big part of it spins-off as a product of karma.

Every individual born, undergoes so many experiences, right from the time when the newborn makes it into the world, its first experience is not being able to breathe, instantaneously there is a feeling of discomfort (dukkha). Surprisingly, without being taught, the infant opens its mouth and starts to cry, which becomes its first mental impression (samskāra). In that cry, it realizes the comfort of being able to breathe. Barely a few seconds into the world, the infant registers that the feeling of discomfort can be converted to a feeling of ease (sukha), its first anubhava is planted in the memory.

A baby unacquainted with language soon exhibits a behavior (vyavahāra), when uncomfortable it starts crying, and this becomes remembrance (smriti), the child learns this in a very short time. Gradually we see that the samskāra and smriti reinforce each other.

Whenever we experience discomfort, we spontaneously change our gear to comfort. Our life is spurting with millions of anubhavas as we live and grow older. Every anubhava stored as either sukha or duhkha is strongly cemented and owned up by our ego (asmita), we then take complete ownership of the pleasure and pain we experience.

When the identity of ‘I’ acts as a catalyst, the whole dynamics of anubhava changes. There is a clear demarcation of the boundaries of sukha and duhkha, we get attached (rāga) to sukha and detached (dveṣa) from duhkha, this is true of every human. A desire to prolong pleasure, recreate pleasurable experiences, at the same time aversion or feeling of avoidance towards anything which is likely to be painful.

A natural consort of rāga and dveṣa is fear (abhiniveśāḥ), fear creeps in deep down, of losing what we want, and getting what we don’t want. As we grow we realize the fleeting nature of experiences, we get into a never-ending loop of smriti and samskāra which keep feeding each other, consequently, a strong cycle is established.

We enter into a vicious cycle because of what we remember of the anubhava and the feeling associated with it. As we go through so many such experiences, these are adding layer after layer to our nature and therefore altering our svabhāva, we don’t react to the same person or same thing, in the same way, our reactions change based on the experience we are fed with, hence each person has a unique nature.

Someone who has never seen a coastline might be amazed at the sight of beautiful balmy beach where the waves are gently crawling to the shore to drench the sand, the tinkling of the wave-music could have been enthralling, creating a pleasurable experience.

At the same time, someone who is pulled into the same waters by a full tide might have had a very painful experience, something that s/he never forgets. The sight of a beach will take the individual back to this painful experience, consequently invoking fear. The beach is the same but the experiences are totally different.

Throughout our lifetime we are creating new karma, with every thought, word, and action. This is called sanchita karma. There are some consequences that we live out in the course of our lives but attributed to the fact that we generate so much karma one lifetime is not enough.

The seeds that have been planted do not have time to germinate, those seeds are stored in the subtle form as our past impressions (vāsanas ) or desires, even after the physical form perishes, leaving behind the sum total of all the karmic impressions that we have accumulated over many lifetimes. Out of the stockpile of all the unmanifested desires (sanchita karmas), there will be some which are very strong, these take immediate form as our prārabdha karma.

In Vedantic literature, there is an analogy. The archer has already shot an arrow and it has left his hands. He cannot recall it. He is about to shoot another arrow. The bundle of arrows in the quiver on his back is the sanchita; the arrow he has shot is prārabdha (effect of past karmas); the arrow which he is about to shoot from his bow is āgāmi (effect of future karmas). Of these, he has perfect control over the sanchita and the āgāmi, but he must surely work out his prārabdha. He has no option but to experience the past which has begun to take effect.

When we ask ourselves a fundamental question – “Why are we born in a certain place, at a certain time to a certain set of individuals?” The answer is prārabdha!

Every one of us is eternally trapped in this cycle of karma, it is the balance sheet of our actions not just in this state of existence, rather a sum total of the current and the past births, which essentially decides our fate.

Possessing a highly evolved intellect (buddhi), it would be a disgrace to be born as a human and yet not make the right use of this invaluable faculty to generate beneficial karma for flawless progress into the inner dimensions. Yoga makes it practical and viable to compress the cycle of evolution into single life.

Theory of Karma says when there is a thought it translates into words, actions and all of these have corresponding consequences. Good thoughts, words, and actions create beneficial effects whereas wrong thoughts, words, and actions create harmful effects.

Therefore, our thoughts are game-changers. Thoughts spring up in the mind, they have an enormous potential to modify the state of our mind, creating a whirlpool, this is referred to as vritti.

Vritti becomes the central and most essential part of Patanjali Yoga Sutras. The second of the Patanjali Yoga Sutras put it very precisely as

yogaha citta vritti nirodhah

योगः चित्त वृत्ति निरोधः

(Patanjali Yoga Sutra 1.2)

yoga = joining/union/integration

citta = consciousness of the mind comprising of:

a. manas- the cognitive faculty of sensory input

b. buddhi – intellect

c. ahamkāra – sense of self/ego

vritti = modifications/fluctuations/versions

nirodha = restraint/inhibition

“Yoga is a cessation of the fluctuations of the mind.”

The intent of yogic practices is to silence the uncontrolled mind. In the yogic frame of reference, the presence of vrittis creates a hindrance to our progress. To describe this, Swami Vivekananda uses the metaphor of a lake. Citta is the mind-stuff, vrittis are the waves and ripples which impinge on its surface, these ripples obscure the bottom of the lake.

It would only be possible to get a glimpse of the bottom when the ripples have subsided and the water is calm. The bottom of the lake is our own true self, the lake is the citta and the waves are the vrittis. When the fluctuations of the mind subside, then we are able to observe our true form. This is presented with great brevity as the third yoga sutra by Sage Patanjali.

tadā drasṭuh svarūpe avasthānam

तदा द्रष्टुः स्वरुपे अवस्थानम्

(Patanjali Yoga Sutra 1.3)

tadā = then/at this time

drasṭuh = perceiver

svarūpe = in its essential and true form

avasthānam = established or abiding

“Then the perceiver abides in his/her own true form. “

This realization comes from within and cannot be comprehended if the mind is colored or conditioned by likes and dislikes, false beliefs, false thinking, and misconceptions. All these wrong notions are our usual patterns of thought which are related to ego (asmitā).

Fluctuations (vrittis) of the mind, are of five types:

- Pramana is correct knowledge

- Viparyaya is incorrect knowledge

- Vikalpa is imagination or fantasy

- Nidra is sleep

- Smriti is memory

We are undoubtedly exposed to these five oscillations in our minds and beyond suspicion identify ourselves with these modifications but our thoughts are mostly attracted to and focussed on viparyaya and vikalpa which have a negative effect on our minds.

For example, when we watch a movie, we get deeply engrossed in the characters so much so that we start experiencing emotions of fear, joy, sorrow, love, hatred, etc., despite knowing that it is just a movie. We identify ourselves with the actors and innocently forget that we are mere spectators.

When we learn to stop identifying ourselves with these false, erroneous, imaginary beliefs, the murkiness in the mind settles, allowing the emergence of sublime transparency. This is beautifully described in the fourth Yoga Sutra of Patanjali.

vritti sārūpyam itaratra

वृत्ति सारूप्यं इतरत्र

(Patanjali Yoga Sutra 1.4)

vritti = modifications/fluctuations/versions

sārūpyam = identification/conforming with

itaratra = otherwise/at other times

“Otherwise the perceiver identifies with the fluctuations of the mind.”

Yoga, when practiced with reverence to following eight limbs, brings about a holistic, transformative, and sustained change in the state of our minds.

Ashtanga or the 8 tools of Yoga are:

- Yama

- Niyama

- Asana

- Pranayama

- Pratyahara

- Dharana

- Dhyana

- Samadhi

Out of the eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga, Pratyāhāra, the fifth limb acts as a bridge between the external forms of yoga (bahiranga) and internal forms of yoga (antaranga), which moves the practitioner from external practices of Yama, Niyama, Asana and Pranayama to subtler forms which are Dharana, Dhyana, and Samadhi.

The word ‘pratyāhāra’ originates from the Sanskrit prefix prati which can also mean “return, exchange, or away”, āhāra is anything that we take into ourselves from the outside. Pratyāhāra is thus disengaging ourselves from external stimuli to create a peaceful and positive inner environment.

In today’s world of a fast-paced express lifestyle, which is in rajasic in nature, it becomes vital to practice regular pratyāhāra. External stimuli have become more overwhelming than ever, making it problematic and difficult for our sense organs, which are constantly being bombarded with a never-ending stream of inputs.

When we instantly react to the information fed by our senses, we are dragged away from the calmness within and are thrown into an ever-fluctuating external world. Our mind gets disturbed, and we end up reacting, resorting to impulsive behavior forgetting our own true nature, our calm and contented self.

We can start by disengaging from certain aspects that work against us, such as unhealthy food, toxic relationships, and useless information that we consume. It is especially important to practice distancing ourselves from mobile phones, laptops, TVs, at least for a few hours every day. Initially, it needs our willpower but as we get familiar with the changes in our mind and body we can do it effortlessly.

It is easy to relate pratyāhāra practice with the help of āsanas, and it becomes a perfect podium for self-discovery. By regular practice, we release physical tension built up in the body. Asanas are a preparatory and vital step for the mind to become quiet and receptive to the next phases of yoga.

During āsana practice, cultivate elements of pratyāhāra by leaving the external world behind, and by being fully present on the mat. Be aware of the senses and observe the reactions to them. As we learn to focus the mind, senses will oblige and follow.

Movement of energy corresponds to the direction of the mind. Our mind is constrained to take only a certain amount of sensory inputs. The practice of pratyāhāra helps in directing the mind inward, away from external stimuli. If the mind is controlled, the senses are controlled also. To begin with, we can start by directing our mind to one aspect only, breath is a good place to start.

Next time when in relaxation postures such as śavāsana or sukhāsana, allow the mind to focus on the subtle sound of breath, once the mind gets used to this on a regular basis, it will naturally focus more on the inside instrument.

Lord Vishnu’s second avatar is the Kurma Avatar, kūrma means tortoise, a symbol of perseverance. In this avatār, lord Vishnu’s main purpose is to provide support. The Tortoise retracts itself into its strong and hard shell when it senses any danger. The same applies to us when we are thrown with a myriad of problems in the outer world.

We can gain courage and strength by connecting with our own inner self. Pratyāhāra, the ability to withdraw from our senses is a great tool. We must cultivate this extremely powerful habit of depending on our own inner strength while restraining from relying on happiness and joy from the external world.

Another great quality of the tortoise is its lifespan, it is one of the longest living animals on earth, the slow and sturdy movements, accompanied by long and deep breathing makes it an emblem of longevity and stability. Practicing yoga with stability and ease gives rise to harmony within the physical body. This aspect is meticulously put forth in the Patanjali Yoga sutra:

sthira-sukham-āsanam

स्थिरसुखमासनम्

(Patanjali Yoga Sutra 2.46)

sthira = strong/ steady/ stable/ motionless

sukham = comfortable/ ease filled/ happy/ light/ relaxed

āsanam = posture/ seated position/ physical practice

In the story of Tortoise and Rabbit, we are all aware that the tortoise wins the race, similarly, when it comes to yoga there are no shortcuts for success. “Slow and steady wins the race”. Tortoise is always content and at peace in its journey. Santosha (contentment) is one of the most important aspects of self-discipline. Being comfortable and feeling at ease wherever we are is very essential.

Yoga is a process of gradual discovery and growth. Just as āsana practice takes time, so does training the mind. We cannot jump into inverted postures such as the headstand on our first day of practice, this does not mean we cannot eventually get there. Patience, consistent practice, determination, and devotion take us a long way in the yogic journey.

Explore Marga “Ayurveda to Yoga”

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.