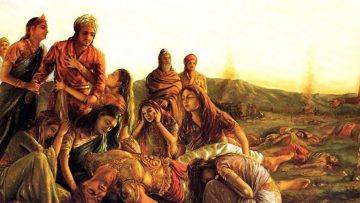

Five millenniums ago, after the Great War fought on battleground Kurukshetra between all but two warriors of Aryavarta, when King Yudhishthira asked Ved Vyasa about how he should go about rebuilding his kingdom, Vyasa told him to seek the advice of General Bhishma. Son of Ganga and King Shantanu, pupil of Guru Parashurama, administrator-warrior-thinker-strategist par excellence, this monument of a man lay on a bed of arrows on the battleground, consciously waiting for the opportune time to let his soul leave his body. With his death would go all wisdom, all knowledge, all perspectives about dharma, statecraft, kingly duties.

And war.

The ensuing discourse between Bhishma and Yudhishthira comprises the largest of 18 parvas, books, in the Mahabharata. At 12,890 verses the Shanti Parva holds little more than one-sixth of the entire 73,640-verse text of the Critical Edition. Broadly, this parva is divided into three parts, Rajadharma parva (law of statecraft, governance), Apaddharma parva (laws of emergencies, calamities) and Mokshadharma parva (law of salvation, metaphysics), although each influences the other, in a seamless blending, with dharma being the uniting feature and the constantly-repeated motif.

If Bhishma were alive today, Prime Minister Narendra Modi would ask him four questions around war.

First, should India go to war with Pakistan? Although Pakistan has been in a state of war against India for seven decades, using Islam as a weapon, 72 virgins as an incentive and suicide jihadis as fodder, the fifth technical war between two nations is a little way ahead. In the first four wars – one each in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999 – India defeated Pakistan and sent it home, only to return. On its side, India got busy with other problems, such as fighting poverty and illiteracy, fixing unemployment, delivering economic growth, and creating civilisational narratives. Like dogs that run after vehicles, Pakistan has been nipping India’s our heels as we accelerated our economy to becoming the world’s fifth largest, expanded our civilisational footprint and pursued a deeper engagement in world affairs, over the past seven decades. Toleration has its limits and, as discussed earlier, that limit has been crossed, the thousandth nip has been made, Pakistan’s Shishupala moment has arrived, and India has risen to its rajasic state.

Bhishma’s answer would have been on the following lines. Protecting the state, and through it, its people, is the first dharma of a democratically elected government (he uses the word ‘king’ but we are now in the 21st century governance structures). He would have reminded Modi of the six essential requisites of sovereignty. One, peace with a foe that is stronger. Two, war with one of equal strength. Three, marching to invade the dominions of one who is weaker. Four and five, halting and seeking protection if weak in one’s own fort. And six, sowing dissensions among the chief officers of the enemy.

Driven by the toxic mix of fear, insecurity and a wayward Islam, the Pakistani establishment has been in the grip of a death wish. It has created an organised industry that manufactures terror, uses young and unemployed bodies as tools, keeping its own families safe in London. This, to Bhishma, would have been an adharma. This is a righteous war, he would have told Modi. By not fighting it for the past three decades since Pakistan changed tactics to using terror as state policy, India has suffered. If you turn away from war, Bhishma would say, it will unleash another round of violence on your people, on your soldiers, on your security establishment, on the very soul of the nation. So, protect your people righteously and slaughter your foes in battle – fight.

Second, what sort of war should it be? Pakistan has been consistently sending terrorists across the border to kill Indian citizens and soldiers through acts of terror. It has been giving cover to and overseeing these operations from inside Pakistan, directly through the ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence), a state within a state, and indirectly through non-state actors, such as the Masood Azhar led Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) – responsible for the 14 February 2019 Pulwama attack – Hafiz Muhammed Saeed led Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), responsible for the 2001 Parliament attack and 2008 Mumbai attacks. And then there is Dawood Ibrahim, the mastermind behind the 1993 Mumbai bombings. All three roam about freely in Pakistan, under the protection of the country’s military. So, the battlefield has changed since Bhishma commanded the Kuru army – it’s not kshatriyas versus kshatriyas (soldiers versus soldiers); it is state-created, soldier-protected terrorists killing innocent citizens. How do you fight such a war?

Bhishma’s answer, however, remains timeless. One that desires the destruction of a foe should not put that foe on his guard. This was done well at Balakot, when India crossed the line of control and bombed Pakistan. Further, one should never exhibit one’s ire or fear or joy – this is something China’s multi-designated leader Xi Jinping does very well, and India because of its democratic pressures does very badly. Bhishma also said that without trusting one’s foe in reality, one should behave towards him as if one trusted him completely, speak sweet words and never do anything disagreeable. India’s public posturing has been controlled, with media leaks driving narratives.

By returning Wing Commander Abhinandan Vartaman, Pakistan has played its cards well. It seeks to de-escalate tensions, disarm the aggression, gain the moral high ground – and revert to terror. There is no guarantee that Pakistan will move a millimetre towards destroying terrorist infrastructure in its borders or bring Azhar, Saeed and Dawood to justice. By ignoring it, being willing to take the casualty and giving little room for manoeuvre to Pakistan, India has played this well too.

Another pressure point for Indian policymakers is technology. In the age of social media riding the world’s lowest-cost data carrying infrastructure, rage is just one tap away.

At a time when vital excitability is the currency of discourse and a never-experienced-before rajasic upsurge driving it, part of warfare has shifted online through psychological operations. On the Pakistani side, the military controls these conversations. On the Indian side, the narrative is controlled by herds – peace-loving groups on one side, justice-seeking on the other, with a large middle watching. When every conversation is public and every action dissected, how does a state work in secrecy?

Had elections not been looming, Bhishma would have said India should wait long and then slay his the foes at the right opportunity, when the enemy won’t expect an attack. This point of opportunity is key – once it passes away, it can never be had again. Pakistan does this very well through its terrorists. India needs to play this game, but through righteous means. Bhishma goes on to say that while the victory should be decisive, killing a large number of troops is not a good idea. Finally, he says, excited with wrath and bereft of forgiveness, boys only seek quarrel. Given this, Bhishma would tell Modi to ignore the media, traditional as well as social, and focus on action, with media management left to one senior minister – the media-friendly Arun Jaitley, the calm and composed Nirmala Sitharaman or the feet-on-the-ground Sushma Swaraj.

Three, what would be the best victory? Rubbing Pakistani leaderships’ nose into the ground would be easy but may not deliver outcomes. Given Pakistan’s terror DNA, even the best intentions may not sustain. The bigger question is: what will Pakistan do with its biggest export industry of terrorists? Traditional change incentives in this journey to economic well-being and social respectability are few. It will definitely mean a downgrade on both, in their personal finances and lifestyles as well as on the perception side as they will be seen as cowards for giving up the ‘holy war’.

Bhishma would have an answer even for this complexity. Confronted with Pakistan’s immoral and adharmic moving parts, he would first say that Modi should seek victory without battle.

Victories achieved by battles are not spoken of highly by the wise. Through an intense diplomatic engagement, Modi has followed that advice already. He kept the diplomats of the world aware of what was going on at every point – after the Pulwama terror attack, before the Balakot strike, and after it. The success is there for all to see: the entire world, including China in an unexpected change of stance, is pushing Pakistan to get in line.

Fourth, now that the diplomatic victory is in the bag and military resolve has been made clear – even the disguised nuclear threat by Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan (“I ask India: with the weapons you have and the weapons we have, can we really afford such a miscalculation?”) – India should cut the gangrene of terrorism. In the rather unlikely scenario if Pakistan chooses war over peace, its economy will self-destruct in a month, if not a week. Bhishma would tell Modi to extract tribute. But since India is not the aggressor, it is only defending its people, what can it extract?

Two ideas. One, hand over the terror triad of Dawood Ibrahim, Masood Azhar and Hafiz Muhammed Saeed to India so we can bring them to justice. Two, show that Pakistan’s intent of using terror as state policy ends by visibly destroying terror camps in Pakistan; a team from India and the United Nations (UN) should verify results. Pakistan can see Balakot as its coming of age moment, when it finally decides to join the comity of civilised nations.

While concluding, Bhishma would tell Modi to never back down. The nation and its citizens come first; everything else follows. Protect it with all your energy, all your will, this is your first dharma, he would say.

This is a dharma-yudha, a righteous war between good and evil, fight it in every way, use every tool you have – military, diplomatic, communications, economic – and win it. For too long your country has languished under Pakistan’s terror assault. Today, the nation is shedding off its tamas, inertia, and embracing the rajasic state. It is willing to suffer. It is willing to support. It needs to win this war. Do not fritter this energy – do not disappoint your people, do not push them back into becoming lambs for slaughter.

This article was originally published by the Observer Research Foundation and has been reproduced here with permission.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.