(Editor’s Note: In these trying times of worldwide lockdown and spread of incurable disease we bring to our readers a series of experiential articles from common people who have dealt with difficult situations through different ways. Be it Mindfulness, meditation, yoga or rituals mankind has attempted to overcome the obstacles faced and the games the mind plays on oneself. These articles are in no way an absolute way to resolve mental health issues and we would advice our readers to consult specialists for clinical depression.

In our first article we bring forth the concept of Dukkha as perceived by the Indic culture.)

The traditional India, the India that was present until just yesterday, before the opening up of economy in the 90s was a world full of dukkha, but empty of depression. This is what makes me wonder, whether depression is the way of the Shakti telling us that pain can never be completely eliminated from life. When you remove physical, causal, and understandable pain from life, that is dukkha, an unexplained, un-caused and chronic pain sets in, which we now know as depression.

Yes, the world of my childhood was full of pain. I feel no shame or embarrassment in accepting it. It is quite too often that enthusiastic Hindu activists portray the pre-modern, pre-Islamic times as times of uniform and unmitigated bliss of every kind, spiritual and material. This is as untrue as an assertion that Islam brought equality in India.

The Hindu India was not a place without pain. There was much suffering, much pain in life even then too. But the pain was understood in its true context: that it is the result of our own past actions and that karmic cycle of pleasure and pain has to be broken by our efforts towards self-realization. The pain was causal. It was understandable, it was physical. And that is why it never became a mental disease, it never turned into depression.

I say that dukkha was causal because no one in my childhood used to blame their pain on the system, or the tradition. There was no amorphous institution or State entity, or a concept like patriarchy or misogyny, which could be blamed for every pain that one experienced. There were very specific causes of every kind of pain, both worldly and spiritual.

Individual pain was understandable and always had plausible causes. Thus, every woman blamed the Pandit who married her to her husband as the cause of her pain. Every man blamed his father for the same. If something bad happened to the child, it was the magic of the jealous neighbor. The mother-in-law was of course the ready object as the source of pain, so was the daughter-in-law in the older circles. No matter how greater the pain was, it was always attributed to some very specific cause.

Jyotisha often helped. I have all the respect for the Jyotisha as a real discipline and a means of knowing, but we cannot deny that it also had a psychological effect on people. If something good had not happened till now, it was in store in future. If something very bad had happened, then it was understood as karmic debt paid off.

The theory of karma also came to help. Every arbitrary evil, like an accident resulting in death, was the result of the previous karma. Every case of social exploitation was explained in the same way. Either the person who was suffering had exploited the exploiter in the previous birth, or he was going to in next birth. In one case there was the consolation of karmic debt paid off. In other case there was the pleasure of vengeance.

In any case, the balance would always come to zero. There was a sense of justice, running deeper than the reach of Law or the arms of the State. It was not even a religious sense of justice. It was greater than even faith in personal deities. It was directly connected to one’s own deeds, as karma and phala siddhanta. No matter how bad things got, Hindus were always encouraged to hold back from doing something evil, otherwise it will come back to bite them again in next birth.

There was no dearth of pain and suffering in the traditional society. There were pandemics; there were deaths in accidents; deaths in illnesses as small as malaria. Poverty always haunted most of the population. Most people were just one week of illness away from falling into chronic debt. Almost everyone knew the pain of losing someone dear to one’s heart. What is unthinkable to most mothers now, the loss of a child, was the part and parcel of motherhood back then. You had many children, some lived, some died. It was as simple as that.

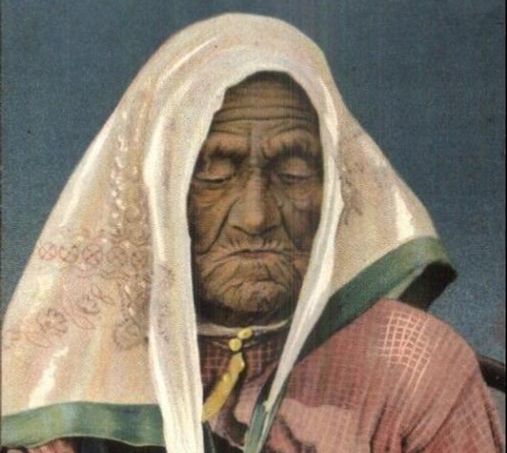

My paternal grandmother lost three children out of seven. My maternal grandmother lost seven out of thirteen.

Yet, everyone took that pain into stride. Yes, they had the consolation of karma. Yes, they had the support of faith. But even more than that, the sense that life was in equal parts pain and pleasure was common knowledge. That pain was an integral and inalienable part of life was firmly established in everyone’s psyche, even children. Suffering was routine, and that the routine took the edge off of it. With the knowledge of karmic debt being paid off, suffering was also cathartic. It did not destroy people, as depression does. It used to build people, make them stronger from all the suffering and pain.

Gradually after the turn of the century, poverty was eliminated for a great section of society. Starvation no longer killed anyone. Wars no longer killed people directly, at least in most parts of the world. Things no longer were so hard to attain. Pandemics seem to have become a thing of the past. Malaria no longer killed people. Children stopped dying as infant mortality dropped. The very sense of losing children gradually receded away into a distant memory.

This temporary moratorium on physical suffering, bought costly at a premium price in future, lulled all of us into a false sense that life is all about pleasure and enjoyment, and that pain is aberrance; that suffering is unnatural, that evil is human invention.

When misfortune did strike in face of an accident, it was no longer bearable. Losing one’s children just destroyed the parents. With just one or two of them, there was no possibility of finding solace in other children. Temporarily eliminating physical pain did more harm than help. It made us lose the strength to fight and overcome pain.

On the other hand, as the physical suffering receded, and as atheism and rationalism also set in, life suddenly gave way to an unexplained, non-causal, chasm in life: known as depression. Everyone now had everything; a job, all the freedom in the world, no more patriarchy, no more misogyny, no more ‘imposition of religion’ or ‘meaningless and superstitious tradition’. Poverty was unknown to most. Everyone had a lot of articles. Everyone had tasted some kind of sweet. Everyone had travelled to some other part of the world, or at least his own country.

With no physical reason of suffering, and with no spiritual discipline to accompany this alleviation of physical suffering, there set in depression. It was unexplained. People started saying, they ‘just don’t feel good anymore’. Everything was so easily attainable and always available, including easy sex, nothing was exciting anymore. With no one telling them what to do, what to eat, and how to dress, freedom lost its charm. With all kind of boundaries disappearing; and in the absence of bondage, freedom lost all its meaning. With infectious diseases receding into the past, chronic diseases like diabetes set in, diseases which are causeless, just like depression.

In other words, we just exchanged one set of suffering for another.

The suffering in the old times was mostly physical. It almost always had cause, and if it didn’t, our tradition invented one for it. The new suffering was causeless, unexplainable. With nothing hard to get, nothing to excite them, and nothing to elevate them to spiritual planes either, people were just bored. As boredom became chronic, a sense of emptiness set in. With no cause of physical suffering, even the smallest of things bothered us. Some comment by our friend, some article missing from the shopping mall was enough to send us teetering down the den of depression.

In the traditional society, not ‘tolerating anyone’ was financially and socially impossible. In the new scheme of things, ‘tolerating someone’ was suddenly an option, an option that increasingly lesser number of people took. At first there was a sense of relief but they soon realized that along with the obnoxious they also threw the charming out the window. They realized that along with banishing ‘intrusion in personal life’ they also banished lovely and necessary companionship.

Thus we see the spectacle of teenagers committing suicide just because someone calls them fat, and to think that just a few decades ago, women could lost seven out of thirteen children and yet live to a ripe age of ninety five. Looking at them going on about life, as defiantly as ever, nobody would say they led a sad existence.

This is why depression is the absence of dukkha.

When the physical pain is eliminated by artificial means, the mental pain sets in. When the periodical pain is eliminated, the chronic pain sets in. When the causal, explainable pain is eliminated, the uncaused, unexplainable pain sets in. It finds ever new ways to plague us. Believing in the pipedream of one-sided life of pleasure, enjoyment, fun and prosperity, we have forced pain to take the form of amorphous, unexplainable and uncaused depression.

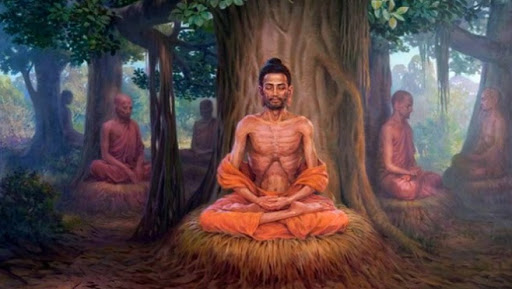

Pain is there to stay. We need to wrap our minds around it. Pain cannot be eliminated but only transcended and for that our tradition of Sanatana Dharma had millions of ways, one of which was meditation. Our gurus, like Samarth Ramdas, like Ramana Maharishi, like Nisargadatta Maharaj, along with our Shastras, have stressed that there is no way to eliminate pain, or dukkha. To eliminate dukkha, we need to eliminate sukha first. To eliminate dukkha, we need to transcend it, through meditation, through bhakti and through quiet contemplation of the Divine. It is important to not lose one’s rooting in adhidaivik and adhyātmik realms.

दु: + ख = unfavourable/bad + space When space around “I” is not good (सु), it is duhkhkha. The context here is what we are referring to as “I” at given time and situation.

As per sānkhyayoga- the body (made up of 5 jnānèndriya [sensory organs], five organs of action [karmèndriya : mouth {speech}, hands, legs, reproductory organ and excretory organ]) is referred to as bāhyakaraN (बाह्यकरण). This is termed as bhautik. Anything that can be perceived with help of these five organs is bhautik. Anything pertaining to bhautik (material) is called adhibhautika. {[Manas-buddhi-ahamkāra]-chitta} – these four aspects of us is called antahkaraNa (अंत:करण).

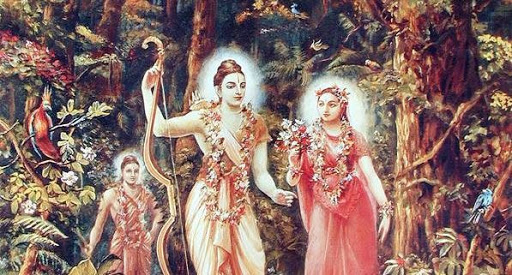

Pure consciousness, origin of chètanā is called puruSha (or ātman). The flow of chètanā is always from puruSha to outside. Meaning, outside everything exists because it is being illuminated/energised by this outward flow of chètanā (जगत प्रकाश प्रकाशक राम – If world is light, source of that light is rām). Rām here refers to same chètan puruSha which illuminates the eight-limbed Prakriti attached to Him.

Prakruti (प्र + कृत = one who intensely acts/is acted upon) does all the karma. And faces all their consequences too. All the consequences of our own previous karma that keep haunting us, is called tāpa (ताप) which come in three, shall we say, flavours. Problems/consequences pertaining to physical world (adhibhautika – pertaining to body), problems/consequences pertaining to AntahkaraNa (man-buddhi) which we call as adhidaivik tāpa. Thirdly problems/consequences (of our own previous actions ) pertaining to ahamkāra and hindrances in that ultimate realisation (adhyātmik tāpa).

Hence, is how if by our own purushārtha, we reduce our adhibhautika tāpa by human ingenuity, our previous karma finds a way to affect our physical body via route of manas-buddhi ie adhidaivik.

Our gurus, like Samarth Ramdas, like Ramana Maharishi, like Nisargadatta Maharaj, along with our Shastras, have stressed that there is no way to eliminate pain, or dukkha. To eliminate dukkha, we need to eliminate sukha first. To eliminate dukkha, we need to transcend it, through meditation, through bhakti and through quiet contemplation of the Divine. It is important to not lose one’s rooting in adhidaivikand Adhyātmik realms. We need to do corrective/compensatory actions (called sādhanā or kriyamāNa karma) to try and mitigate the consequences of our own past karma. With all previous explanation of what sukha and dukhkha means, we will proceed to understand these verses.

Rāmadāsa swāmi has brilliantly put this thus –

सुख सुख म्हणता हे दु:ख ठाकोनि आले

भजन सकल गेले चित्त दुश्चित्त झाले |

भ्रमित मन वळेना हीत ते आकळेना

परम कठिण देही देहबुद्धी गळेना ||

When my mind was relaxed, thinking I am now going to experience sukha, some dukhkha inexplicably erupts out of my Sanchita karma. All my mental resolve, my drive to do compensatory actions (sādhanā) vanished instantly at the first instance of dukhkha and my very chitta became disturbed. My mind (which understands where I should go and what I should do), suddenly becomes unwieldy like a wild horse and loses the compass of knowing where my real Hita is. This attachment and identity to the physical body as I become even more stronger (creating a positive feedback loop since it is physical body and mind that is experiencing dukhkha)

Swami ji continues how he overcame this –

उपरति मज रामी जाहली पूर्णकामी |

सकळ भ्रमविरामी राम विश्राम धामी ||

घडि-घडि मन आतां राम रुपी भरावे |

रविकुळटिळका रे आपुलेसे करावे ||१४||

When he had uparati of rāma, all delusions ceased. Every waking moment now is filled by Rāma and my mind now rests at the abode of rāma. Now every waking moment, mind is filled with presence of rāma. Oh epitome of suryavansha, now accept me as your part.

जळचर जळ वासी नेणती त्या जळासी

निसिदिन तुजपासी चूकलो गूणरासी

भूमिधर निगमासी वर्णवेना जयासी

सकल भुवनवासी भेटि दे रामदासी

This one is deeper. Has roots in vishNusukta of Shruti. Like fish while in water is unaware of water it is in. But when it comes on land and returns to water that relief can’t be described.

Similar is the relief when a mind suffering from trividha tāpaand seen and unseen problems returns to resting place (vishrāmadhāma of rāma). When the all-pervading (sakalabhuvan vāsi) one meets rāmadāsa, the troubles of mind vanish. The all-pervading (literal meaning of word vishNu) is celebrated as Trivikrama by us. When one’s antahkaraNa realises thay everything is pervaded by vishNu (like water pervades the very fabric of sponge) that is when the final bondage of prakriti and purusha breaks and one achieved kaivalyapada.

The first part of this article was authored by Pankaj Saxena and the later part on Dukkha, including Swami Ramdas’ insights was authored by Kal Chiron.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.