Abstract

Oral storytelling traditions are important elements in any culture that helps preserve and pass on the practices, rituals, belief systems and the norms abiding by which a society functions. It serves as a bridge connecting the ancient to the present. This paper aims to introduce in detail and understand the structure of the one such unique storytelling tradition that is practiced in the southern part of India, predominantly in Tamil Nādu – Villu Paatu, the folk oral storytelling tradition.

Introduction

Stories are universal and storytelling is as ancient as humankind itself. In every culture across the world and in every civilization, storytelling existed and still exists to pass on the cultural and traditional values and practices that form a backbone pertaining to a particular society or a community. From gathering around the campfire-telling tales of our ancestors, to modern day television, we all talk through stories.

One can’t deny the fact that the oral tradition in any culture existed way before writing and documenting came into practice. All the important information in the ancient times hence was passed on orally from one generation to another, using stories, songs, prayers, poems, proverbs, riddles, lullabies to name a few. Right from the cavemen days to the times of the kings, history has recorded storytellers and bards as important people in a tribe, community or a kingdom who acted as a bridge in connecting the unknown or lesser known to the commons. These storytellers were believed to be the most skilful people in the land, who could convey effectively and connect to the majority of the people paving cooperation among society right from the hunter gatherer times.

The storytelling traditions in India may be classified into the classical and the folk traditions, both of which were said to have a certain structure or protocol. To learn the art and to present them requires years of vigorous training and practice. One among the many of the folk oral storytelling traditions in India, is the Villadichan Paatu or the Villu Paatu that originated in the south of India, which despite having a structure to it has evolved into a free-flowing fluid style of storytelling form. This paper aims to analyze the same.

Villu Paatu or the Bow Song

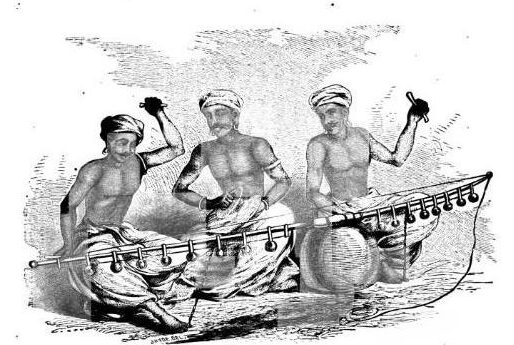

(Figure 1: Villu Paatu – the Bow Song)

If you happen to catch a glimpse of the “kodai vizha” or the “charity festivals” in the temples, especially in the Tirunelveli, Thenkasi, Thoothukudi and Kanyakumari districts of Tamil Nādu, which earlier were a part of the then “PaandiNaadu” (that were ruled by the Pandiyan kings) you cannot miss the troupe of artists sitting on a stage telling stories in a sing song manner, in conversation with each other and at the same time with the completely hooked audience. You can then be sure you are witnessing the “Villu Paatu” literally translated into the “Bow Song”. What makes this oral tradition unique is the presence of Muthamizh – the three important aspects of Tamil language, “Iyal (poetry), Isai (music) and Nadagam (drama)” all beautifully weaved in one form ¹. It is this aspect along with the special unique instruments used during the telling that makes it one of the most enjoyable experiences for the listener.

The legend behind the origin of Villu Paatu

A war weapon turned into a musical instrument.

This story has been passed on orally in the “Villu Paatu” artist community for ages now. There has been no written evidence of the same. ¹

The story dates back to a time when kings ruled the resplendent regions of India. A “Citrarasan” – a king who ruled a smaller province in the then “PaandiNaadu” (or the southern land of Tamil Nādu ruled by the Pandiyan kings) went on a hunting expedition along with his soldiers and some of his ministers. Tired after a day’s hunt, the king decides to rest under the shade of a tree and the kill that he had made is laid in front of his eyes. The gruesome sight of the animals young and old lying dead in front of him makes him ponder. “Who am I to take these innocent lives away? What have I done?” His heart aches at the thought that he has committed sin. He asks the advice of his minister who counsels him to sing out loud his thoughts. Using the Bow that was used for killing, now as an instrument to make music along with the earthen pot that they used to store water, as the one to balance the bow, the king starts singing seeking forgiveness for his action to the divine, with all his heart. The soldiers gathered there join in the process asking questions and reinforcing what the king said with an “Ammam, Ammam” translated to “Yes, Yes”, and the healing takes place, inside the king. The king is surprised to see animals in the forest gather to listen to the song. He goes back home a happy man and spreads the art of the bow song that helped him heal. People learn the art and start singing stories of Gods and Goddesses, of local folk deities. This later gets included in the festivals of the temples in their Kodai Vizha or the charity festivals, in those regions and came to be known as the “Villadichan Paatu or the Villu Paatu” the bow song, where the “Ambu “or the arrow is replaced with “anbu” or love for all and the bow, the war weapon becomes a central piece in the narrative art, symbolic of evolution, from slaying to storytelling, nearly 2000 years ago.

In the words of Subbu Arumugam Aiya “Kolai Karuvi Kalai karuvi annadhu” ¹

Traditional and Contemporary Villu Paatu artists

While there is no record of the name of the king or the people whom he taught the art form to, people like “Thovalai Sundaram Pillai, Iampillai, SatturPichaikutti, TitunelveliPulikuttipulavar, YazhpanamChinnamani, ChokkaloShanmuganathan, Nachimar koviladi Rajan, KalaimamaniKovilpatti Muthusamy Thevar, KalaimamaniVilathikkulam Rajalakshmi, Kalaivanar N.S. Krishnan, Kalaimamani Subbu Arumugam and Poongudi Arumugam were some of the oldest well known artists.¹ ²

Kodai Vizha – Charity Festivals

The “Kodai Vizha” or the charity festival for the village deities, is a prominent festival that is celebrated glorifying the folk Gods and Goddesses, that is very unique to the southern regions of Tamil Nadu, especially the Tirunelveli, Thoothukudi, Thenkasi and the Kanyakumari districts. It usually happens in the month of “Aadi” (mid-July to mid-August) and the months of “Thai, Maasi, Panguni and Chithirai” (Mid-January to Mid-May). The purpose of the Kodai Vizha is to please the village deities and seek blessings to achieve the desired state the devotee asks for and be free from any undesired ones. This is accomplished by worshipping the deity, through a puja ritual by decorating the deity with flowers, offering food and traditional comforts. An elaborate puja called “Thipparathanai” that leads to devotee possessions and the performance of the bow song where the deity is glorified (by singing the story of the deity) completes the main ritual elements of the “Kodai Festival” ³

Villu Paatu in Kodai Festival

Sri Mutharamman Koil Kodai Vizha, 2018. An Overnight Villu Paatu Performance

Figure 2: Credit: Youtube

Some more research about the Kodai festival has led me to some unique information that helped in understanding why the “Villu Paatu” was the chosen art form in the “Kodai Festival” in comparison to others. The kodai festival is very specific to the southern regions of Tamil Nādu. So it was only natural for an art form that has its roots in the same land to be an integral part of the main ritual. Any Kodai festival runs up to three days and three nights long. The main event or the puja usually happens from late evening until the dawn of the next day. It is during this time the “Villu Paatu” artists sing the story of the village deity.

The folk deity’s temple is usually at the outskirts of the village where the forest path begins. To ward off the wild animals of the jungle from coming into the temple during the nights, where the rituals took place, there was a need for something that kept the place alive, filled with beats and songs. Also, the elements of verse, music, drama and conversational style of telling, glorified the “village deity”, by singing the respective popular local folklore, which was very apt when celebrating the local deity. This hence:

- Should have kept the people awake from late evening until dawn and during the puja and

- Should have triggered the “Bhakti” element or deep devotion in the devotees with its soulful storytelling

Both of which only enhance the experience for the listener. It has been noted by many that at the end of the performance some listeners in the audience have said to be very high on the devotion and have been possessed by the deity, who then answers the questions of the other devotees. ⁵

The intensity of the song and the sounds of the musical instruments is said to invoke the “emotional elements “in the listener. The recitation of the biography (carita) of the folk deity hence compels divine presence. ³

The Traditional Villu Paatu in the earlier days were said to have run from 9 pm in the evening to 4 am in the morning. When the epics were sung, it would go up to 18 days, but with changing times it is now anywhere between 3 to 6 hours.

Stories sung in Villu Pattu

The traditional Villu Paatu (bow-song) singers, divided their stories into two categories – the “PiranthaKadhai” (The stories of the birth) and the “IrandhaKadhai” (The story of the death). ³⁴

The Birth Stories:

These narrate the mystic origins of the Gods and Goddess that are grouped under the “divine birth” (or the deiva piravi – painless supernatural births). They originated in the Kailasa or the heavenly realm of Shiva and Parvati. Victorious over the evil demonic forces they descend to the human world and receive homage, festivity and confer boons.

The stories of folk deities “Kaaliamman, Muttaramman, Sasta, Maadathiamman, Muppidathiamman, Sudalaimadasami, Karuppasamy” are some that belong to this category.

The Death Stories:

They are also referred to as the “Irandhupattavaadai” or “Vettupattavadai” (the horror of violent death). The heroes and the heroines in these stories are humans who were killed or otherwise met with wild, violent and unjust death. After death they ascend to heaven, receive divine powers and then descend to earth and seek vengeance for their unjust death and later temples are built in their honour and are worshipped by local people and become a part of the local Sampradaya,

“Kurukkulanchi, Muthupattan, Pulangondal, Chinnathambi, Pattavarayar, Bommakka – Thimmakka etc., belong to this category.

In the three-day Kodai Festival, on the first and the third nights the birth stories are sung and on the second night a death story. The singing of the latter is the climactic event of the festival and experiences a ritual intensity, absent elsewhere. This intense singing is believed to make the deity descend and possess the audience. Both the audience and the possessed are caught in this grip. The possessions in the birth stories are considered relatively weaker. ³

Apart from the stories of the folk deities, the epics and legends are also sung. “The Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the legend of Harishchandra and the legend of “Satyavan Savitri” etc. to name a few.

Instruments used in the telling

The main instrument used during the Villu Paatu telling is the “Vil” or the bow that is a set up that includes a bow, an earthen pot, the string and the sound bells. ²

The bow is made from the “VairamPaindha” Panaimaram, (meaning, the strongest of the lot which does not break when bent. It is usually a possibility of 1 in 100)¹ wood from the palm trees that is bent into the shape of a bow (known as the “VilKadhir”). In both corners of the bow, cups are hung. These are tied together by a string. Sound making bells or chalangai are hung at regular intervals in the string. The number of bells hung according to the tradition are always odd in number, usually 11. ²

The center of the bow is made to rest or attached to the center of the earthen pot. The earthen pot does not have a “Vilimbu” or an edge. This pot is made to rest on a ring that is made from ”hay” (known as the Puriannai), which prevents the pot from falling.

- Veesukol (Sticks to hit on the string)

This is a small stick with a handle. The primary singer in the troupe (or the poet) hits the string of the bow using this, making specific rhythms to support his singing.

- Udduku

The Udduku is a percussion instrument that plays an important role in intensifying the emotions in a telling. This is a smaller version of the traditional “Udukkai”. When invoking the deities, these are hit to a loud volume.

- Kattai (Sticks to hit the earthen pot)

Sticks made from a special tree are used to hit the earthen pots to support the singing. In these there are two variations.

The “ThattaKattai” that is used to hit on the pot and the “PathiKattai”that is used to hit the mouth of the pot.

- Brass Cymbals

These are two round plates (or sometimes smaller – known as the kinnaram), that are hit together to produce a rhythm.

In the recent years the Villu Pattu artists also use instruments like the Tabla, Harmonium and Keyboard to support the singing,

The Performance Structure

Right opposite to the sanctum sanctorum of the deity, a stage is raised. It is on this stage that the Villu Paatu is performed.

The performing group consists usually of five people, divided into the right hand side singers (Valampati) that includes the lead singers, cymbalist and the “annavi” singer (one who repeats after the main singer) and the left hand side singers (idampatti) that includes the pot player, drummer and the wooden block players.

The performing group sets the instruments on the stage and before the performance, a small prayer is recited and “deeparadhana” a lit camphor in a plate is shown to the instruments, to seek blessings from the deities.

The entire Villu Paatu performance can be divided into seven segments. ¹ ²

- Kaapu

This is the first stage of the performance where songs are sung in praise of the Gods that the artists pray to, seeking their blessings. This usually is “Vinayagar” (or Ganesha the elephant head God, who is considered to be the remover of obstacles) and Sarasvathi (The Goddess of knowledge and arts).

The song usually starts with

“ThandhanathomendrusolliyeVillinilpaada, vandharuvalKalaimagale”

- Varuporul (agenda of the day’s performance)

This is the second stage of the performance where a brief about the content of the performance (the Gods, the people or the theme in which the performance is based) is done.

- Salutations to the Guru

The artists for the day show their gratitude by singing songs in praise of the teachers who taught them this art. This is the third stage of the performance.

- AvaiAdakkam (The humble artist)

This is the fourth stage of the performance where the artist humbles himself in front of the audience whom he refers to as the learned people. This also is the stage where they seek forgiveness for any mistakes that could happen during the performance.

- Singing the praise of the land

The fifth stage of the performance is richness of either the land they perform, or the land where the stories belong to which is conveyed to the audience through songs.

- The Story time

The sixth or the most important stage of the performance is the time when the story for the day of either the village deities or the main theme is done. This is where one witnesses the three aspects of “Senthamizh”- the poetry, the music and the drama, come alive through live songs and conversational style of storytelling.

Kalaimamani Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan (an eminent Villu Paatu artist) here tells that “There is another unspecified “element that is added to the Villu Paatu performance that is the most important that brings about the connection to the audience -” Humour”

- The Finishing Song (VazhthuPadudhal)

This is the last stage of the performance where the artist thanks the wonderful audience for their patient listening and sings songs wishing them good health, wealth and happiness in the days to come.

The spin off

The traditional Villu Paatu is so ancient that in parts of Tirunelveli there are even proverbs that came into being as a result of this wonderful art and has been passed on orally for many generations now.

(The Proverb: Villadichan KovilileVilakethaNeramillayam, KudamadichanKovililekuthuvillakethanadhiillayam)²

A very interesting incident is associated with the origin of the proverb. Once during a kodai vizha, a Villu Paatu artist was performing through the midnight. The people in the temple were so engrossed that they forgot to notice that the lamps in the temple were burning out. The artist very humorously as a part of his performance sang the lines which later became the proverb in the region.

The proverb meant, there is no time (for people) to light lamps in a temple where the bow song is sung. There are no means to light lamps in the temple where the earthen pot is played.

The moment this was sung, the people realized that the lamps in the temple were burning out and they were lit.

Like Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan said to me in an interview, humour was the secret ingredient added by the artist to convey the right messages at the right time.

The question that arises in one’s mind is, when did Villu Paatu take a spin off from its traditional way into also addressing social issues?

Kalaivanar N. S. Krishnan.

(Figure 3: Kalaivanar NSK)

Nagercoil Sudalaimuthu Krishnan, (1902-1958) popularly known as Kalaivanar (lit. ’Lover of arts’) and also as NSK, was the reason behind this positive change. The man who is considered as the “Charlie Chaplin of India” and was an Indian actor-comedian, theatre artist, playback singer and writer in the early stages of the Tamil film industry – in the 1940s and 1950s, started his career as a Villu Pattu artist.

An ardent Gandhian, he spoke about Gandhi’s “Salt March” in the 1940’s incorporating humour that conveyed the message in a subtle way.⁶

NSK, then paved the way for people like “Subbu Arumugam Aiya ‘‘(Now 94, and has won various titles and accolades as a Villu Paatu artist).

Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan, the daughter of Aiya. Subbu Arumugam, fondly recalls the incident that was narrated by her father. In the year 1947, Subbu Arumugam happened to write a song for a Villu Paatu performance that he performed in his school, infused with humour about the “independence movement”. Presiding the function in school that day was NSK, who encouraged Subbu to come to Chennai after his schooling from Tirunelveli and write which later became NSK’s brilliant masterpieces. Learning the art of Villu Paatu from a revolutionary in the field, it only came naturally to Subbu Arumugam to take the context of Villu Paatu to focus on social issues, after the demise of NSK in the year 1950. (He still uses the “Villu” that belonged to his teacher NSK, that was later passed on to him)¹. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, agriculture, education, medicine and literature slowly found its way into the art form, supported by eminent leaders in India like Rajaji. For Subbu Arumugam, it was more about the people’s development by bringing in social issues rather than the traditional stories.

The Villu Paatu Surge:

With the advent of Doordarshan in the mid 1970’s the art form started travelling through television media to the living rooms of the people, mainly to create awareness regarding various health issues like AIDS, family planning, various government education schemes and policies to the common man. ¹

Did this affect the traditional telling? Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan says, “No”. The Villu Paatu in Kodai festival continued with its splendour. An art form stays alive as long as the society accepts it. The people accepted the Kalaivanar baani (style) of telling as well as the traditional style. However, one cannot fail to notice one difference that stands out between the traditional Villu Paatu artists performing in Kodai festivals and city dwelling artists like Aiya. Subbu Arumugam. “While the former still sees it as an art form that is passed on orally and one can see them sing it from their memory, artists like Subbu Arumugam who create “new performance pieces“ are seen on the stage with a book that they refer to”-Dr. Eric Miller, in a telephonic conversation with the author of this paper.

(Figure 4: Kalaimamani Aiya. Subbu Arumugam (Narrator) with his daughter Kalaimamani Bharathi Thirumagan to his left, son Gandhi playing the earthen pot, and grandson Kalaimagan with the percussion instrument)

While the performance structure (with the new age) was kept intact the time allotted for each stage of the performance considerably reduced because of the time allotted for the performances. Sometimes in the television programme only a 20-minute slot was allotted and the artists were required to fit in what they had to say in the given time.

The Challenge

Despite the art form being unique and connecting well with the audience, the Villu Paatu artists find it difficult to even make ends meet. For some like the traditional artists, the performance has been their bread and butter. With the focus of such traditional telling to only the kodai festivals and with the advent of the internet age, it has seen a decline in the number of Villu Paatu artists being called to perform on stage.

(Figure 5: Tirunelvelli Sankarammal performing in Kodai Vizha)

Is this only the plight of the traditional artists? Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan says “It’s pretty much the same with artists like them who had moved to the cities hoping for a better reach”. While they do not deny the fact that there has been international recognition, the uniqueness of the performance itself of having to take a team with them everywhere, and the costs involved is exorbitant.

(Figure 6: Kalaimagan, Grandson of Aiya Subbu Arumugam)

Also travelling to a country other than theirs, it becomes mandatory for them to also include languages such as English and sometimes local languages to establish a connect with the audience. The upcoming Villu Paatu artist Mr.Kalaimagan (grandson of Kalaimamani Aiya. Subbu Arumugam) is one such artist.¹

The boon and the bane

“To find a true Villu Paatu artist is a rarity these days. The main narrator in the performance will have to be a person well versed in poetry, music and drama. But it’s very hard to find everything in one person.” says Kalaimamani Bharathi Thirumagan.

So a narrator will have to depend on a poet to write his songs. Similarly, to find and form a troupe of accompanying artists becomes a challenge. Owing to the lesser performances, artists opt for other means of income, like accepting other musical kutcheris, teaching etc. Kalaivanar NSK had a troupe that he could depend on. Kalaimamani Aiya. Subbu Arumugam, trained his daughter, son and grandson to play different roles in the performance. But when it comes to training new people in this art form, the uniqueness of this art form of having five people poses a challenge. To find an ensemble of a main narrator/poet, the support narrator, the pot player and the percussion player becomes hugely difficult. It also requires training for the performance with everyone present. Given the lack of availability owing to other commitments that give them additional monetary benefits, forming a permanent troupe (like how NSK and Subbu Aiya had) becomes difficult.

Revival

An art form that originated as a “healing form”, that usually did not require any formal training in singing (The traditional artists were not trained singers but are passionate singers who bring in the emotions through their original voice and in a way, they believe is true to them), ² encouraged people to learn this art. But art forms like these are endangered because of the constantly changing interests of people with the advent of technology. For the survival of the traditional folk forms, it then becomes important to transpose these into the new world, including the electronic aspects of the same. ⁷

(Figure 7: Oral Storytellers performing, live for an online audience)

The responsibility then lies on the rasikas (the audience), the government and the various sabhas, that book artists, to take it forward. Giving them a stage and seeing more people in action will encourage the younger generation to learn this art form.

Conclusion

This paper is an attempt to understand and document the origin, the rituals along with the performance structure of the traditional Villu Paatu form of singing the folk deities and also exploring how and when the later inclusion of social, political and economic awareness as a theme in the same came into picture. While both the baanis (styles) have flourished, one has to agree that this beautiful organic art form that gives the artist the liberty to organically blend the socio-political awareness into the traditional art form (which is hugely accepted by the audience) is seeing a decline. As rasikas it is our responsibility to see this art form thriving. And this paper I believe, will be a window to the same for the “story lover/folk lover community“ and hence the larger audience that can be reached through them.

Acknowledgements

My sincere gratitude to Dr. Eric Miller, founder of World Storytelling Institute, Chennai for giving access to some of his works on Villu Paatu and the contacts of Villu Paatu artists that I could talk to and gather the necessary information needed for my paper and to have kindly taken the time to review my paper.

Heartfelt thanks to Kalaimamani Mrs. Bharathi Thirumagan (Villu Paatu artist and daughter of Kalaimamani Aiya. Subbu Arumugam, an exponent of Villupaatu) for encouraging, appreciating my work and patiently answering all my questions regarding the art form.

References: Citation

¹ Telephonic interview with Kalaimamani Bharathi Thirumagan by the author of the paper

²Tirunelveli Mirror: All about Tirunelveli – Villupaatu

³Origin Myth and Rituals: An Ethnographic of Muthupattan by S.Simon John

https://www.mukpublications.com/resources/vol.13-2-7.pdf

⁴ Stories of Birth and Death in Villupaatu of Tamilnadu by A.Mariappan

https://snarepository.nvli.in/bitstream/123456789/3844/1/JSNA%28123%2916-24.pdf

⁵ Questions of Discipline and Genre: Storytelling Studies and Subbu Arumugam’s Bow song by Eric Miller.

⁶ Tamil folklore studies: The contemporary scene and its background by Eric Miller

https://storytellingandvideoconferencing.com/29.html

⁷ The Asian century of folklore scholarships: Reflections on the Chennai conference by Eric Miller

As a part of Indian Folklife: A quarterly newsletter from national folklore support centre

Vol.3, Issue 2, Serial no: 15, March 2004.

Feature Image Credit: gulfnews.com

IndigenousStorytellingTraditions

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.