Iconography, History and Archeology

The image of ‘Nataraja’ with its mesmerizing binaries of dynamic movement and unchanging stillness is an icon from the Hindu tradition, popular in India and around the world. Across time civilizations around the world have engaged in art, sculpture, music, and dance, i.e., aesthetic expressions and symbolic representations of one’s own culture, beliefs and spiritual explorations. In the Hindu tradition Siva’a AnandaTaandavam and Krishna’s Rasamandala are well-known expressions through dance.

‘AnandaTaandavam’ the cosmic dance of Lord Siva – the destroyer and the keeper of time, holds associations with Natya Shastra the text on dramaturgy. In the temple of Chidambaram resides the bronze sculpture of Nataraja belonging to the Chola dynasty. Worthy of special mention among the Chola rulers is the pious Sembiyan Mahadevi, known as the great queen. She contributed significantly through her generous patronage, ensuring sustenance and development of temples, art and architecture, as well as of the Nataraja icon in particular which became the emblem for the Chola dynasty, of South India.

Chidambaram Mahatmyam is the legend of the temple which elaborates further on this worship of Siva not as the lingam but in his dancing form. Takarada, A., & Makai, D in ‘Lord of the Dance [1] points out, “The symbolism has been interpreted in classical Indian texts such as UnmaiVilakkam, MummaniKovai, TirukuttuDarshana and TiruvatavurarPuranam, dating from the 12th century CE (Chola Empire).

(Figure 1: A 10th-century Chola dynasty bronze sculpture of Shiva, the Lord of the Dance at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Texts: Anshumadbhed agama, Uttarakamika agama)

Among the contemporary commentaries, the writing of historians of art, The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays by Coomaraswamy, Ananda K (1918) [2] and T. A. Gopinatha Rao’s (1997), Elements of Hindu Iconography [3] appear to be among the popular references among scholars for the symbolism and interpretation. In these the references were primarily to the Chola dynasty and to texts from 9th-13th century.

Art historian Padma Kaimal in her essay, Shiva Nataraja: Shifting Meanings of an Icon [4] suggests that Narataja icon goes back few centuries further. “By the seventh century the hymnists Appar, Sambandar, Sundarar, and Manikkavasagar had sung of Chidambaram’s already ancient sanctity” She goes on to write, “The songs of traveling hymnists would have acquainted audiences outside Chidambaram with its anthropomorphic, dancing god, allowing such copies in bronze and stone to evoke his cultic home explicitly for such viewers.”

These she mentions, played a role in popularizing Nataraja and the ‘Karaiviram’ bronze copies of, which could have contributed, she attributes to the reprisal of the icon from the stone relief in granite.

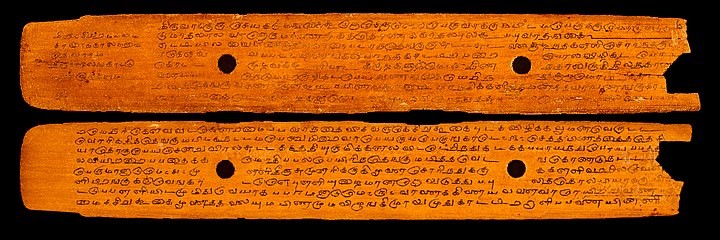

(Figure 2: A palm-leaf folio of Tevaram manuscript copied in a Tamil Shiva temple about 1700 CE. The manuscript, like many Hindu texts found in South India, starts with a contents list. The title of the hymns set is in its colophon. The ragam (scale) and talam (beat) are included on the manuscript leaves to guide the singers and musicians. The above set is one of 230 Tevaram folios currently preserved in the British Library).

Along a similar line of thought, archaeologist Sarada Srinivasan in her research paper [5] takes the dates of the icon further back. I quote, “This paper explores the origins of the Nataraja sect in the state of Tamil Nadu in southern India. The trajectory of the dancing Shiva is traced from the processional worship of metal icons outside the sanctum to the cultic elevation of the Nataraja bronze into the sanctum at Chidambaram. Archaeometallurgical, iconographic and literary evidence discussed shows that the Nataraja bronze, depicting Shiva’s anandatandava or ’dance of bliss’, was a Pallava innovation (seventh to mid-ninth century), rather than tenth-century Chola as widely believed. That this formulation was informed of ‘cosmic’ or metaphysical connotations are also argued on the basis of the testimony of the hymns of Tamil saints.”

These texts and the writings of the scholars from various disciplines bring forth the study and interpretation of not only Nataraja but also Apasmara, the dwarf demon under the foot of Nataraja. This demon is known as Muyalkan in Tamil language.

Popular culture: music

KalaiThookiNindraa popular song in praise of Nataraja, rendered by many renowned Carnatic musicians was composed by MarimuttAPillai (1712-1787). The lines in the often missed out 3rd Caranam go, “Muyalakanunnaithookee”, referring to the demon below the foot of Nataraja.

Story of Apasmara

The story of Apasmara as seen in the SkandaPurana, is also found in the Tamil KovilPuranam, and SthalaPuranam of Chidambaram temple. Endocrinologist Shashadri in his paper mentions, “The ceiling of the Shivakamasundari shrine in the Nataraja temple complex illustrates this legend in a series of frescos.”

In the deodar forests the rishis had become arrogant with power gained through arduous worship and rituals. They were wreaking havoc with their drunken pride. Siva had to go and resolve this issue. He went as a handsome Bhikshatana (mendicant) and took Vishnu along in the form of Mohini. The rishis were smitten by Mohini’s beauty and the wives of the rishis enchanted by the Bhikshatana. On returning to their senses, the angry Rishis performed a yagna from which rose creatures to fight Lord Siva: a serpent, tiger, a lion and a dwarf demon Apasmara. Siva faced, fought and killed the other three creatures but Apasmara is one of the rare demons who had unconditional immortality, unlike Hriyankashipa, Jarasandha and others of the ilk. And so Lord Siva as he danced his furious cosmic dance brought Apasmara under his right foot and kept the foot steadily there while at the same time he swung his left foot up in the air. His left palm points at the raised foot and not at the foot at the bottom over the demon.

The arresting image of Nataraja is notably expressed in 108 poses in the Indian classical dance form of Bharathanatyam. Natarajasana is considered advanced asana in yoga for senior practitioners.

Epistemology and Ayurveda

In his article on Epilepsy in ancient India, in the official journal of the international league against epilepsy, Bala V. Mani [6] writes, “Epilepsy is defined as Apasmara: apa, meaning negation or loss of; smara, meaning recollection or consciousness.” He reaffirms what former Ayurvedic texts have stated “Apasmara is considered a dangerous disease that is chronic and difficult to treat.”

Sawarkar G, Sawarkar P [7] in his case study explains, “The main features of Apasmara are impairment in memory or awareness. Even though most of the times, it is considered as manasrogas (psychic disorders), it is not a manasroga. Apasmara is one of the diseases, which affects both sharira (physical) and manas (mental)” Swarkar goes on to refer to a case study showing how the treatment is more effective when both the body and mind are treated, including Shirodhara in this case.

Endocrinology and Apasmara

“Mysticism surrounds the dancing form of the Nataraja. But does Nataraja dance upon an endocrine mystery. Does the demon under his feet Apasmara literally forgetfulness or does epilepsy have an endocrine disorder? The short limbed stocky eye popping dwarf with possible mental retardation with a name that suggests epilepsy throws open a host of endocrine diagnoses. From cretinism to the original descriptions of pseudohypoparathyroidism here is one view of the medical mystery under Shiva’s dancing feet” proposes Krishna G Seshadri in his paper, Endocrinology and the arts at the feet of the dancing Lord: Parathyroid hormone resistance in an Indian icon [8]. This doctor of modern medicine offers an interpretation of the dwarf demon. Apasmara is called Muyalakan in Tamil language. “Muyal” is hare/rabbit in Tamil. Epilepsy in Tamil is “MuyalVali”, named thus due to the convulsive fits whose pace is similar to the breathing of the hare when it gets the smell of a predator, he clarifies.

He concludes with an interesting interpretation that akin to the endocrine glands and the quantities of hormones they release into the system, which is minute but whose perturbations cannot be ignored, so too is the demon of ‘ignorance’– Avidya, Ego: Muyalakan, small but whose perturbations are intense and need to be ’cured’ by appropriate action, such as keeping steadily under the foot of Nataraja.

Astronomy and Nataraja

In recent times, in the modern discipline of astronomy, exploration and understanding in collaboration with knowledge systems of ancient civilizations including Hindu is prevalent. For example: The popular TEDx talk hosted by Austin University, where Dr Raj Vedam [9] elucidates about the ‘moon and its 27 satellites’ and the how Hindu story of moon having 27 wives is not only indicative of specific knowledge but also of clever pneumonic devised to orally pass it on. Another example is the documentary film ‘Secret life of plants’[10] in which people of the Dogan, an isolated tribe in Africa have clear detailed knowledge of a satellite that goes around the star Serius, which is invisible to the naked eye. And this knowledge has been passed on for thousands of years orally through the wise men and kept alive through the cultural practice of the Segi festival of the tribe that occurs once in fifty years.

(Figure 3: The scope and understanding of the modern discipline of astronomy is expanding and accommodating various aspects that were at one time perhaps considered beyond it. Physicist Fritjof Capra’s quote on the plaque below the 2 meter high Nataraja statue, gifted by the Indian government to CERN, the European Center for Research in Particle Physics in Geneva reads, “Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies ancient mythology, religious art and modern physics.”)

According to Ian Crawford, professor of planetary science at University of London, the cosmic dance of Shiva as Nataraja represents particle physics, entropy and the dissolution of the universe.

From this cross-disciplinary exploration of Nataraja and Apasmara, let us return to the title of this paper: Siva and Apasmara – Trajectory of knowledge acquisition, for the scope and relevance of the information and interpretations.

It is interesting to note that, apart from Nataraja, the only other roopam of Siva where Apasmara is apparently present is Dakshinamurthy. The Adi Guru, guru of the gurus, the mouna guru: one who transmits knowledge of truth through silence. Dakshinamurthy is a form of Siva associated with knowledge. Here too like in the Nataraja icon, the demon of ignorance Apasmara lies under a steady and sure foot of the gently seated figure.

(Figure 4: Dakshinamurti, 16th century, MuséeGuimet (museum), Paris)

Pedagogical significance

My area of interest is the philosophical interpretations available through the lens of various scholars and the relevance of these in the context of learning and knowledge acquisition. I am a performing artist: I narrate stories orally. I am also an art-based educationalist. I train teachers on how to teach employing story-arts as a pedagogical tool in the classroom. It is interesting to see how various aspects of the symbolism and its varied interpretation can be gainfully employed by the teaching community. I imagine that Siva, the Adi Guru represented this approach to ignorance ‘the dwarf demon’ Apasmara, to guide in understanding the trajectory of knowledge-acquisition. As a concept this is also a reflection of the educational approach which must have existed.

The three striking concepts that are worthy of introspection especially for educators are:

Firstly, Apasmara was one of those rare demons who had unconditional immortality. The immortality of Apasmara is interpreted as immortality of “ignorance” itself emphasizing its essential role in the journey towards knowledge. Of course the purpose of teaching is to destroy ‘avidya’ in the learner however, ignorance or avidya ‘as a concept’ shall exist and needs to exist in the world. The philosophical understanding is that ignorance is the stepping stone in the journey of ‘seeking knowledge’ and by its very existence gives value to ‘knowledge’. This is a clear demonstration of giving due worth to ‘not knowing’ in the process of ‘knowing’. The understanding therefore is that by journeying through ignorance alone does one reach the goal of knowledge.

Second, while acknowledging the existence and the role that ignorance plays, we as educators are urged at the same time, not to forget that ignorance must be called faced squarely in the eye and kept under the steady and sure foot so that it does not take over the control and wreak havoc, be it for the individual, for the situation or the world at large.

Third, supremacy of ‘silence’ of the Adi Guru over ‘nonsensical speech’ of the demon of ignorance.

Let us consider how this might have been integrated into the pedagogical practices of India. I find that the philosophical underpinnings of existence of a creature like Apasmara who is an unconditionally immortal dwarf “demon of ignorance”; echoes through the educational system and literature here in. The associations in Ayurveda of Apasmara with loss of memory and unintelligent speech, also holds metaphorical relevance.

Let us look at stories, songs, rhyme and poetry. These are some of the clever pneumonics created to ensure that complex knowledge could be orally transmitted, easily understood and well-recollected even by the ignorant listener. Giving due credence to the fact that ‘loss of memory’ is ‘unavoidable’, that it is an immortal concept so to speak, the practice of rote learning “kantastha” and the method of repetition towards this goal, was empathized. Moreover, in order to ensure that a learner could move step by step with knowledge acquisition, the progression chart went from ’learn by rote’, ‘continue repeating until thoroughly memorized’ and finally ‘comprehend the memorized’.

In our literature and learning, ignorance is also acknowledged creating a space for ‘doubts’ and ‘expressing of doubts’. ‘Shanka’ or doubt has received suitable space in our literature. Be it Upanishads, Puranas and other texts one finds an inside listener representing the ignorant/confused/unaware/doubting outside listener/reader; and possibly indicating ways of doubting and even suggesting how to ask questions. This inside listener asks doubts or questions or has conversations with a wiser person who can engage purposefully in the dialogue. For example: Garuda placing his doubts about his Lord Vishnu before Kakbhushandi in one section of Tulasi Das, Ramayana.

Ignorance is also perceived as an opportunity and a need to generate curiosity. At the start of a narration, the traditional storyteller often generates curiosity about the story he/she is going to narrate, and doesn’t assume (and hence expect) that the audience know enough to be automatically interested in the storytelling. For example there is a listener of the lowest order who just wants to be entertained. His or her ignorance is recognized and accommodated by the composer/narrator but not judged.

Of what relevance might this be for educators today engaged with learners and the process of learning?

A direct application in today’s context of learning would be to understand that the child is ignorant and that’s why we are here to help in the journey. Apparent as this seems, it is not uncommon to hear teachers say, “Why can’t you understand?” While it is the learner’s duty to try and understand, it is also the teacher’s responsibility to constantly consider and try to arrive at what could be the possible obstacles for the learner in the process of learning?

Simultaneously it helps if the teacher is aware and can admit to herself that she despite the best efforts is likely to be ignorant of some aspects of the learner’s life, situations, thoughts and emotions.

Here are a few personal anecdotes to illustrate my points:

There was an instance in a branch of a government-aided English-medium school where a child from class 6 who had been struggling with her studies, ran away and thankfully she was found in a nearby village where a local family out of kindness took care of her, a total stranger to them. Once she returned to school, a senior teacher from class 10 had a long interaction with her. She did not follow a word of English! The teacher then advised the family (illiterate labourers from Rajasthan) to shift her to a Hindi medium school and enrol her in some vocational skill like stitching. In less than a year the girl found her footing and flourished in studies and stitching both. Her primary requirement given her situation was a Hindi medium education. This is an example of how we may be unaware of the challenges the learner is facing.

Here is another scenario. Each of us might have had a classmate/relative who struggled with studies simply because of an undiagnosed problem with eye-sight. The teacher assumes that the student is making excuses for not writing notes when in reality the student is actually not able to see and read the blackboard clearly.

Similar to Ayurveda mentioning Apasmara to be seen not only as a manasroga but also as a shariraroga and accordingly administer solutions that could be physical modifications, so could this be true of the intellectual exercise of learning in the classroom. As teachers we might be ignorant of physical factors that could be coming in the way of mental work. It would be worthwhile examining a situation from this perspective as well. We will make the effort to know only when we admit to the possibility of ‘not knowing’.

We are all likely to memorize those moments in the classroom when we have had mental conversations with ourselves. “Should I ask my doubt? Should I not?” As teachers, making a conscious attempt to create an environment where the learner feels safe to ask doubts and explore without feeling embarrassed and judged is an important pursuit. By this we are conveying to the learner, “You are ignorant about this and it is fine. It is but another step in the process of learning. Go ahead and ask your doubts.”

On the other hand, a fairly recent practice in ‘modern teaching’ of being blindly polite to the learner’s ignorance, mechanically appreciating and giving zero criticism; can have dangerous consequences. Like Siva did with Apasmara, it is our duty to gently but unapologetically look ignorance in the eye, point it out and keep it in check with a steady and certain ‘foot’ Otherwise like the convulsive fits which are beyond the control of the person, ignorance can be disruptively out of control and harmful.

Inquisitiveness is essential to the process of learning. It basically evolves from ‘knowing that one does not know’ and therefore comes the curiosity to know. Compassionately igniting this meta-awareness in the student of her own ignorance, generating curiosity for and confidence in the subject being taught is the responsibility and talent of the teacher.

Like Dakshinamurthy the Adi Guru, “mounam” or silence can be a powerful tool for the teacher as she addresses ignorance. Seen metaphorically, we can receive when we are silent and when we are not filled with our thoughts (perceptions and assumptions). When the teacher chooses to be an empathetic listener, listening silently with her ears, eyes and heart, the chances are certainly higher of being open to “ignorances” both of her own and the learner’s.

As this paper comes to its conclusion it seems apt to end with the philosophical interpretation of ApasmaraPurusha as the demon of “spiritual ignorance” who resides within the city of nine gates of this body. I am reminded of one of the parables on Vedanta narrated by Swami Sarvapriyananda of Ramakrishna Mission. A dhobi reaches the riverside having brought all the clothes to wash, on the back of his donkey. He then realizes that he has forgotten to bring the rope to keep his donkey tethered to a nearby tree, so it wouldn’t wander away while he washes clothes in the river. The dhobi asks a wiseman there for help. The wiseman advises him to pretend to go through all the motions of tying up the donkey as if there is really a rope. The dhobi does just that. On his return he is happily reassured to find the donkey still standing right there despite no rope! He puts the bag of clothes and drags it but the donkey does not budge this time. Once again the wiseman is asked for help. “Go through all the motions and pretend to untie the rope”, he says. The dhobi does just that. And the donkey begins to walk back home!

While some of us are fortunate to receive the guidance of a guru in the journey of spiritual seeking, for the rest an oft suggested antidote to beat the game of the demon Apasmara who makes us forget the true nature of the self and imagine that ‘we are bound’ is to ‘remember remember remember’, repeatedly remember the true nature of the self. Smaranam and NamaSmaranam! I am remembering my ‘thatha’ my grandfather who we all called Ram Ram thatha because he always had Ram Ram on his lips.

I end with a few lines from a song composed by Surdas in which the bhakti poet talks about how easily we get drawn into the transient world and lose the memory of our true self. And then, when it is too late we realize we should have spent a life time remembering!

कहा भयो अबके मन सोचे

पहिले नाहिं कमायो।

सूरदास हरि नाम-भजन बिनु

सिर धुनि-धुनि पछितायो।।

रे मन मूरख, जनम गँवायौ

(Kahaan Bhayo abke man soche

Pahile naahi kamaao

Surdas Hari naam-bhajan binu

Sir dhuni-dhuni paccchataayo…….

Re man murakhjanamgavaayo)

References

- Takarada, A., &Makai, D in ‘Lord of the Dance’

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. “Cosmopolitan View of Nietzsche,” in The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays, Revised Ed., New York: The Noonday Press, 1957.

- A. GopinathaRao (1997). Elements of Hindu Iconography. MotilalBanarsidass. pp. 223–229, 237. ISBN 978-81-208-0877-5.

- Kaimal, P. (1999). Shiva Nataraja: Shifting Meanings of an Icon. The Art Bulletin, 81(3), 390–419. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051349

- SharadaSrinivasan (2004) Shiva as ‘cosmic dancer’: On Pallava origins for the Nataraja bronze, World Archaeology, 36:3, 432-450, DOI: 10.1080/1468936042000282726821

- Bala V. Manyam: Epilepsy in Ancient India. In: Epilepsia. Volume 33 Issue 3, August 4, 2005, pp. 473–475. PMID 1592022. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb01694.x

- Sawarkar G, Sawarkar P. Role of Ayurveda in the management of Apasmara: A case study. J Indian Sys Medicine 2019;7:245-8

- Seshadri K. G. (2014). Endocrinology and the arts at the feet of the dancing Lord: Parathyroid hormone resistance in an Indian icon. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 18(2), 226–228. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.129117

- TEDx Talk UT Austin – Of ancient Star-Gazers and Story-Spinners , Raj Vedamhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jq__DXtfeXw

- Documentary Film – The Secret Life of Plants – (Time stamp 01:07:00 to 01:14:00) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTWcVnMPChM&t=4462s

- A Meta-history of India’s Space Science, The Cosmic Gaze : Open Essay by KeerthikSasidharanhttps://openthemagazine.com/feature/a-meta-history-of-indias-space-science/

Feature Image Credit: dreamstime.com

Watch video presentation of the above paper here:

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.