In the Natyashastra (Science of Art), Bharatamuni shows how the four goals of life or the four puruṣārthas -Dharma (moral values), Artha (prosperity), Kama (pleasure), and Moksha (liberation) are achieved through art. This manifests through the connection of the artist and the audience through ‘Sattva’ which results in rasa utpatti.

In the words of Dr. Puru Dadheech, ‘Sattva’ is akin to the rays of sunlight being concentrated on a magnifying lens. The art magnifies the fourfold components of abhinaya while the audience experiences its effect through the lens of Sattva such that sentiments(rasa) manifest as an involuntary response. This is crucial to creating a spiritual communion (Sahridayata and Sancharyoga) between the artist and the audience and is the crux of ‘sadharanikarana’ as described by Abhinavagupta.

Kusilava vrityartha natyashastra pracharkatvat valmiki muniti

The ‘kusilavas’ described in the Natyshastra or the travelling bards(kathiks) of Valmiki’s Ramayana would use music and dance to convey stories from itihasa (historic episodes connected with Ramayana and Mahabharata). ln the fourth sarga of the Valmiki Ramayan, Valmiki looks for students most likely to do justice to his poem. He teaches it to Kusa and Lava, Rama’s sons who are being brought up in his hermitage, and they learn it by heart.

These two perform the text, not just for themselves or Valmiki, but before a larger audience. Thus began the parampara of Kathavaachan, which was a predecessor of Kathak as a proscenium art form. Significantly, the Kathavachaks were the medium of mass communication where the ‘Vachik’ component of abhinaya was central.

Through the depiction of stories from ithasa, the roadmap was conveyed to the common man in order to achieve the puruṣārthas. This is the beginning of the inseparable evolution of literature(content) and language(medium) within the paradigm of spiritual communication through kathak.

The language of the kusilavas was Sanskrit, which, with time, became a language of the elite. Hence the kathavachaks started adopting colloquial languages that resonated with the masses. The most significant literary influence is of the Ramcharitmanas in 16th CE by Goswami Tulsidas, who brought the Valmiki Ramayan to the common man through use of Awadhi.

The Kathakaars furthered the spread of the stories through this language by connecting them with music and dance. Goswami Tulsidas in his Vinay Patrika talks of Kathakaars while the description of the attire and dance that Surdas writes in his most famous pada, ‘ Ab main nacho bahut gopal (I have danced enough, Krishna)’, is clearly a reference to raasdhari dancers in the Braj region(circa 15th-16th CE).

The raasdhari parampara is the next significant step in the evolution of Kathak and adds brijbhasha into the languages connected with the narratives employed by the dancers. The influences of all these periods is seen in the vastukram or repertoire of Kathak today.

Many shlokas from the Ramayana, transcended from the kathavachaks into proscenium kathak through the teachings of the gharanedaar Gurus of the Awadh kathak parampara.

A Sanskrit shloka depicting the navarasas as experienced by Lord Ram, was an iconic piece performed by Pt Birju Maharaj in his solo concerts – shringaram kshiti nandini virahane (looking at Sita with love), viramdhanurbhanjane (heroic when breaking the bow to marry sita), karunyam balibhojane ( pity and compassion at the burning away of kakasura, the demon who attacked sita), hasyam shurpanakhamukhe ( laughter at Shurpanakha’s attempt to entice him), bibhatsamanyamukhe (disgust at other womans approach to him), adbhutam sindhaugiristhapane (wonderment at the monkeys building the bridge on the ocean), raudram ravanamardane (furious at killing ravana), bhayamaghe (fear at the approach of sin), and munijane shantam (quietude while offering prayer to the sages ).

The idea that Bhakti or devotion can transcend Gyan or knowledge was established by the astachaap poets and other later day poets of the Pustimarg, the path of bhakti established by Shri Vallabhacharya in the 14th-15th century CE. Vallabhacharya expounded the principle of pure non duality or shudda adwaita. The brahman and the soul are but one and realization of Krishna is also equivalent of self-relaization.

Jaydeva (12th CE), considered as many as the precursor to the bhakti movement in India, wrote his composition in eight sections or shringarik astapadis. He was the first poet to emphasize that listening to the lilas of Krishna, can lead one on the path of moksha.

The eight-syllable mantra, śri kṛṣṇaḥ śaraṇaṃ mama (Lord Krishna is my refuge), is passed onto new initiates in Vallabh sampradaya. As per noetic science expert Lynne McTaggart, 8 is the number of people needed in a group, that working together is able to send out a sustainable thought through the universe. In mathematics it is the first cubed number, thus connecting with the Tihai, Trimurthi, and Tridevi.

Shringara to Bhakti of the astachaap also became a central feature of thumris and padas written by Bindadin Maharaj. Thus spiritual philosophies of Bhakti marg reach audiences today, wearing the attire of kathak vocabulary.

Ramcharitmanas is both a source text for literature that can be used in the Kathavaachan tradition of Kathak, as well as inspiration for a number of Kathak compositions. Unique to the text are the interwoven components of Ram bhakti towards Shiva and vice versa making it a union of both Shaivite and Vaishnavite ethos.

The Nataraja is a symbol of the dance of the inner consciousness while Natwar is a symbol of the external manifestation of the dance. Presenting prasangas (episodes) connecting Vaishnavism and Shaivism in Kathak, becomes a profound medium to blend these two energies together (transformation and preservation). The episode of Sati taking the disguise of Sita was presented by Pt Birju Maharaj in Kathavaachan style of Gatbhaav as ‘Sati Bhram’.

Similarly, the entire Tulsidas Ramayan was presented by Kathak Kendra as a Kathak dance ballet ‘Katha Raghunath’ . These dance ballets were a refined presentation of the story telling feature that was central to the Kathavaachan tradition. The ‘Katha Raghunath’ could be considered as a distilled version of the Varanasi Ramlila, as described by Dr Kapila Vatsyayan.

The central theme of the Ramlila is the Moksha attained by every anti-hero at the hands of Rama. The text is recited and sung by the chief narrator and also spoken by the actors. In the Kathak version the text through music and dialogues is presented through orchestral support, while the actors present the sattvika abhinaya.

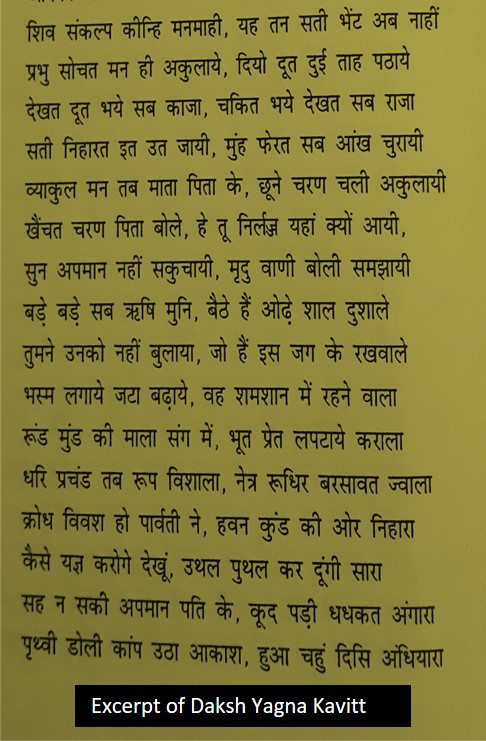

In the Balkanda of Tulsidas Ramayan, Sati Pareeksha is immediately followed by the episode of Daksha Yagna. The description given by Tulsidas has been beautifully composed into Kathak Kavitt by Pt. Lacchu Maharaj. ‘Shiv Sankalpa Kinhi Man Maahi’ (Shiva made an unbreakable resolve in his mind)- We see the occurrence of the above line both in Ramcharitmanas and ‘Daksha Yagna’ kavitt, which is danced today by disciples of late Guru Rohini Bhate (who was a disciple of Lacchu Maharaj), disciples of late Guru Ramadevi Mishra (wife and disciple of Pt Lacchu Maharaj) and other prominent disciples of Pt Lacchu Maharaj like Dr. Padma Sharma and Smt. Kumkum Dhar.

In conclusion, the ethos of spiritual communication runs like an eternal thread of history linking these poets like pearls in a necklace. It is for the kathakaars of today to understand this unified thought and add themselves like pearls into the very same necklace, that connects us for eternity, thus making us ‘patras’ suitable for spiritual communion.

References

- Acharya, Adhikari, ‘The sadharanikaran model and the ritual model of communication: A comparative study’. A paper presented at the Young Researchers’ Conference organized by Martin Chautari, 2012 January 2-3, Kathmandu (2012).

- Anand, Madhukar, ‘Kathak ka Lucknow gharana aur Pt Birju Maharaj’, Kanishka Publishers (2013)

- Dayal, Naina, ‘Tellers of tales: pauranikas, sutas, kusilava vyasa and valmiki’, Thesis, Jawaharlal Nehru University (2009)

- Hari DK and Hema Hari DK , ‘Historical Rama’, Bharat Gyan(2010)

- Maharaj, Birju, Recording, Kalashram Archives (2016)

- Ghosh,Manmohan, ‘ Natyashastra Volume II’ , Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, Varanasi, (2012)

- Mctaggart, Lynne ,https://lynnemctaggart.com/(2018)

- Nagar, Vidhi, ‘Kathak ka Lucknow Gharana’, Hindi Vangmaya Nidhi (2009)

- Narayan, Shovana, ‘ Rhythmic echoes and reflections –Kathak’, Lotus Collection( 1998)

- Narayan, Shovana, ‘Indian Classical Dances’, Shubhi Publications (2005)

- Pattnaik, Devdutt, ‘Who we dance for?’ Devlok, Sunday Midday, Nov. 12 (2012)

- Sahay ,Saket, ‘Electronic media bhshik sanskar evam sanskruti’,Manav Prakashan(2018)

- Sharma, Renu , ‘ Lalit Tribhang’, E-Book, www.alpikaonline.com(2018)

- Singh, Mandvi, ‘Kathak nritya parampara mein Guru Lacchu Maharaj’, BR Rhythms (2006)

- Thapar, Romila History OfIndia, Volume One. New Delhi. Penguin Books India (P) Ltd., (1990)

- Vatsyayan, Kapila Malik, ‘ Ramayana in the Arts of Asia’, UNESCO (Teheran) (1975)

- Walker, Margaret,‘Ancient Tradition as Ongoing Creation: The Kathavacaks of Uttar Pradesh’, Canadian Journal for traditional music 33 -48 (2006)

This article was first published on India Facts.

Disclaimer: The facts and opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. Indic Today does not assume any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.