(This op-ed, “Macaulay’s Shadow Runs Deeper Than We Admit,” written by Anshuman Panda, offers a considered response to Prof. Ashutosh Varshney’s article, “Did English language create captive minds?” published in ThePrint on 25 November 2025.)

Was the Prime Minister only partly right when he accused Macaulay of mentally colonising India? In a recent article in ThePrint (“Did English language create captive minds” dated 25th of November, 2025), Prof. Ashutosh Varshney argued that there were complex and multivalent consequences of Macaulay’s legacy. While many indeed adopted the lens of the colonizer, many others used English knowledge for emancipation, and even development.

The author used the example of three Indian stalwarts of the 20th century: Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Nehru, to build his case. In this article, I argue that Macaulay’s impact was far deeper than it appears, and even when English education empowered Indians, it often did so by subtly reshaping their minds through colonial categories.

Gandhi: A Borrowed Pacifism, an Indigenous Resistance

To begin with, let us consider the example of Gandhi cited by the author. There are two main points which were made: First, that Gandhi developed his idea of non-violence from the Advaita tradition of this land, which sees the oneness in all and thus forbids violence towards another as violence towards self. Second, Gandhi’s inspiration of civil disobedience came through the thoughts and works of Thoreau, Ruskin and Tolstoy.

This has been the general understanding until now, but is it true?

While the advaita tradition indeed talks about the oneness of all creation, it is not the fount of Gandhi’s idea of non violence. What then is the source? A phrase that the author used in his description is revealing: all of us are “children of God”. The idea of humans being children of God, with Father sitting up in heaven, is a Christian idea. The advaita tradition talks about all of us being parts of God, God itself. I am the supreme principle (Aham Brahmasmi), and so are you (Tat tvam Asi).

The distinction is significant, and it shapes the downstream philosophy. In Advaita tradition, while all of us are part of God there is a duty to resist injustice, even with violence as a last resort, for injustice obfuscates (avidya) our Godly nature. In Christian tradition, being children of God, adherents are advised to turn the other cheek and remain meek (The meek shall inherit the Earth), for God will judge each one’s actions on the Judgement Day. We can see that Gandhi’s idea of unqualified pacifism even in the face of aggression was derived from the Christian principle.

On the other hand, while Gandhi points out his influence of civil disobedience as the works of Western authors, Dharampal, in his seminal work Civil Disobedience and Indian Tradition curated from the British archives, established Satyagraha to be an original Indian form of protest even in the 1810s. This is not to question Gandhi’s source of inspiration, but to prove that the people resonated with him because the idea was patently indigenous.

The British records show that when one such Satyagraha happened in Varanasi in 1810, they responded with criminalising such protests, and dividing the population against each other. Thus, they not only broke the self-assurance of people in their own legitimate cause and its strength, they also brought in a fear of reprisals, skewing the balance between the rulers and the ruled. Such actions led to people feeling a sense of subjugation and erosion of agency. It was this sense of subjugation which people rose against when they followed Gandhi on the renewed path of Satyagraha.

Ambedkar and the Myth of Indian “Backwardness”

The example given by the author on Ambedkar is interesting because it represents what is perhaps the biggest psyop of the British in India: the myth that India was an illiterate, casteist, and backward society, in need of external ideas and saviours to truly understand what social democracy and equality meant.

While The Beautiful Tree by Dharampal demolishes the myth of education being a sole preserve of the upper castes and the supposed illiteracy of Indian society pre-colonization, it is his essay on The Question of Backwardness that really lays the issue bare.

The Manusmriti is often cited as the scriptural basis for discrimination, but it is forgotten that it was the British who gave scholarly and legal sanction to some of its provisions, including on caste. The fact that the vast majority of native Hindu kings belonged to the shudra varna, and even that most jaatis claimed a divine origin as espoused in their jaati puranas, was completely sidelined. In turn what was bestowed was the label of backwardness.

Though India has always been a country of many tribes and communities, it has seldom occurred that any community used the label ‘backward’ for itself. There have been periods of pauperization, but such conditions by themselves don’t make their sufferers feel backward. Rather, backward, like ‘barbarian’, is an image one projects onto another who is weaker and doesn’t subscribe to our cultural norms.

Dharampal noted that when the Europeans first arrived in India, it was they who “felt that the Indians applied such an appellation to them (the Europeans) for their manners and greed which were considered barbaric and uncouth, about the colour of their skin which was thought to be diseased, or even the system of dowry which is said to have obtained in eighteenth century England, but to have been looked askance in eighteenth century India.”

When the colonized internalize the view of the colonizer about themselves being backwards, it is a sign that colonization has succeeded at the psychological level, and that the people have lost dignity in their own eyes.

Caste was and is a stark reality in the Indian society, but to undermine the impact of traditions ossifying due to invasions and economic pauperization is unjust. The British froze caste flexibility in colonial records, while simultaneously deindustrializing and draining the country. This overturned the relationships various castes had with each other, while making the deviation from Brahmin varna the metric for backwardness.

Ambedkar’s fight for caste rights happened under that mental framework. Today, that model has been weaponized to fuel caste politics within the democratic setup.

Nehru, Planning, and the Persistence of the Colonial Mind

Finally, the author gave the example of Nehru and central planning by the State post-Independence as an instance of anticoloniality. However, Nehru’s choice of self-reliance and import substitution was not based upon indigenous ideas, but was derived from Soviet Russia. India, with its vast coastline, had never been an isolationist power. Rather, we traded goods and ideas, influencing the entire SE Asia, China, Korea, and even Japan. This could only happen on the back of our strong philosophical ideas and entrepreneurial spirit.

When the economy however began to be planned by the State and imposed top-down, it was the same as how the British had treated Indians, as a people without agency. Rather, it was the opening up of the economy in the 1990s that served more as an indigenous gesture than the erstwhile state planning.

Rather than the English education of Macaulay, it is the reclamation of agency that enables Indians to realise their civilisational potential.

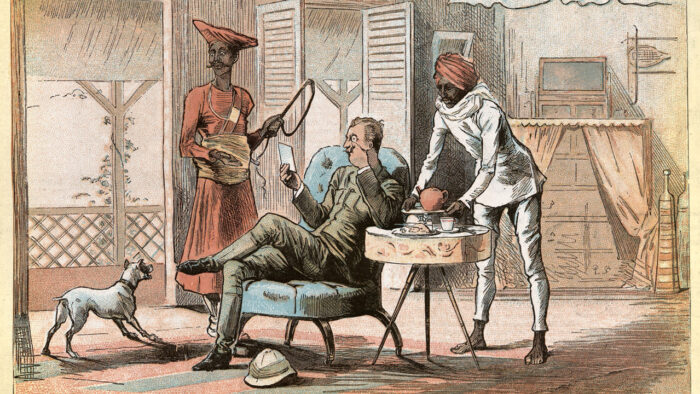

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.