Veda and Vedanta

Most people have heard of the Vedas. However, many are unsure of what exactly the Vedas are, and what the subject matter of Vedas is. Vedas are the undated (undateable?, although many researchers are working on establishing a date), apaurusheya scriptural texts that people in Bharat Desh have been following for as long as can be traced back. Apaurushya means that these have been not been created by any human intellect. No one claims authorship of these texts. These texts have been known to exist in all parts of India, with some variations. It is said that Rsi Vyasacharya codified them into the four Vedas that we now know – Rg, Yajur (Krishna and Shukla), Sama, and Atharva Veda.

Each of these can broadly be seen in two parts. The first part, called Poorva Bhaga or Karma Kanda elaborately describes ways and means to any end. It is almost like a guide to live life at different stages and lists the various actions (karmas) one is expected to take in each.

The end of each Vedas (therefore called Vedanta, the end portion of the Vedas) is called UttaraBhaga or Jnana Kanda. It consists of the different Upanisads. The objective of these Upanisads is to reveal to one the truth of the self, called Brahman or Atma. Therefore, the subject matter of all Upanisads is You.

Of the two – poorvabhaga and uttarabhaga – the former is very large, while the uttarabhaga is small portion at the end of each Veda. While the poorvabhaga or karma kanda helps one live a life of a dharma and earn enough punya to gain both things that matter in this world and in attaining swarga and other desirable lokas after the fall of the physical body, the larger purpose is to prepare oneself to be ready to receive from a guru the knowledge contained in the jnanakanda or Vedanta or the Upanisads.

Prasthanatraya

When one starts on the journey the gain the knowledge, traditionally one learns three sets of texts, called prasthanatraya. These are Upanishads, called srutiprasthana, Bhagawad Gita, called smritiprasthana, and brahma Sutra, an analytical text, called nyayaprasthana.

Bhagawad Gita gives one insight into karma yoga as a way of life, a nishtaa. It also reveals the knowledge that gives the sadhaka what every human being is seeking, moksa or freedom from things one does not want – the sense of being incomplete, of being subject to grief and pain.

Upanisads have only one aim – to reveal the nature of the self (and the jagat, the universe and Isvara). Each Upanisad uses a particular method to unfold this truth, by negating possible universally common false identifications, and then exposing the prepared mind to the reality of the self. Generally, Upanisads are in the form a dialogue between teacher and student. The student (or students) is often highly evolved individuals, irrespective of their age, who have already figured out that there has to be a state of moksa, freedom and, often also the next step – that such a state can be gained through knowledge available in Vedanta.

Here we will focus on Vedanta, and how it is looked at by different masters.

Vedanta

As already stated, Upanisads reveal the nature of the self, I. This knowledge cannot be gained by data gathered by the senses and processed by the mind/buddhi. All of these are instruments or equipment that can reveal information about objects (not just physical objects, but ‘object’ in the grammatical sense). In fact, Mundaka Upanisad says that Bhagawan destroyed us by making these senses outward focused, with no ability to perceive the self, the knower[1]. These senses and the mind/buddhi make it possible for science to uncover knowledge of the universe and the objects therein, but fail when it comes to self-knowledge. We have to turn to Vedanta as the source of this knowledge.

However, Vedanta is in the form of words and words have to be heard/read, understood and made sense of. This process leads to a very high probability of making mistakes in understanding, both because words, sentences, texts are subject to individual interpretation and are also dependent upon the preparation of the mind of the receiver, his/her state of mind at the time of receipt, past experiences and conclusions drawn therefrom etc.

That is the reason why Vedas tell us that this knowledge cannot be gained on one’s own and needs a guru, who has studied in the lineage from his/her guru[2]. In essence, the only way to gain this knowledge is to study the words of the Upanisads under a traditional guru, contemplate on them, remove all doubts and address all questions, examine how one should understand what these words say, even when they appear to contradict the conclusions one has reached based on one’s experiences[3].

Vedanta cannot be assimilated through reasoning and logic for the same reasons[4]. Shraddha, in the form of acceptance of the Vedas, as unfolded by a guru, as the means of knowledge is necessary[5]. Shraddha does not ask one to accept everything blindly, on faith. Approach the learning with an open mind, with the right attitude, question (not with the attitude of punching holes in the reasoning, but to understand), says the Bhagawad Gita[6].

Thus, one has to find a traditional teacher from whom one can learn. However, what if there are different masters who have slightly different interpretation of Vedanta?

Hinduism – Traditional Views

Hinduism accepts many different philosophies and schools of thought, irrespective of whether they accept Vedas or not. Worship in any form, of any God, is accommodated in the Hindu way of thinking.

Traditionally, Hindu thinking broadly divides these systems — called darshans — into those that accept Vedas (Astikas), and those that do not (Nastikas). Among the ones that accept Vedas are:

- Sankhya

- Yoga

- Nyaya

- Vaiseshika

- Purva Mimamsa

- Uttara Mimamsa

These darshanas, other than the last two accept Vedas as pramana but use logic to arrive at the truth and take the support of the Vedas to aid their conclusions. The last two darsanas take Vedas as the only pramana and use logic as a tool to understand the revelations. The commonality is that all of them take recourse to Vedas as a pramana.

Sankhya is based on Sankhyasutras of Sage Kapila and is dated about 500 BE. It is also called nirisvaraSankhya. The creation of the universe is because of the disturbance in the balance between the three gunas – sattva, rajas and tamas.

Yoga is also called sesvarasankhya. It takes much from Sankhya, but accepts the idea of Isvara in creation. Patanjali Muni’s Yogasutra forms the basic text. Yoga deals with the spiritual disciplines to attain quietness of the mind as the means to self-realization.

Nyaya is based on Nyayasutras by Gautama Muni (around 550 BCE) and focuses on logical realism.

Vaiseshika is complimentary to Nyaya and is based on Vaiseshikasutras by Kanada Muni (around 330 BCE) while Nyaya concentrates on logic, Vaiseshika is centered on analyzing and understanding the nature of the universe.

Mimamsa means enquiry. It is seen in two parts – Poorvamimamsa, dealing with karma – rituals, practices and means & ends in the jagat. The main text used is Jaimini’s Mimamsasutras (around 200 BCE)

The UttaraMimasa (latter mimamsa) is also called Vedanta Mimamsa. It is based on the Upanisads found at the end of each Veda (hence Vedanta) and uses Brahmasutra, by Badarayana Muni as the text.

Before we get into looking into the views of the different masters who have interpreted UttaraMimamsa, we will also briefly look at some philosophies that propound a school of thought based on the reasoning of the founder, and not on any scriptural pramana.

Philosophies that do not accept Vedas include:

- Carvaka

- Jaina

- Buddhism (4 different schools)

These philosophies use reasoning as the only means to assert their point of view. However, as already discussed, reasoning alone is inadequate to understand the truth of the self.

Vedanta Mimamsa

Our focus here is on the UttaraMimamsa, which interprets Vedanta, where the truth about the self, the universe and Isvara is revealed. Except advaita, different masters have given their own interpretations of the meaning of the Upanisads. The interpretations are as follows:

- Advaita

- Vishitadvaita

- Dvaita

- Dvaitadvaita

- Shuddadvaita

- Acintyabhedabheda

Of these six, the first three have a much bigger following than the later three. We will restrict our discussions to the first three. All three use Vedanta as the predominant source of knowledge, supported by reasoning and logic.

Cambridge Dictionary defines Philosophy as “the use of reason in understanding such things as the nature of the real world and existence, the use and limits of knowledge, and the principles of moral judgment”. In this sense these darshans cannot really be called “Philosophy”, because their preponderant input is from Vedas. They are, therefore, called darshans, way of seeing. As explained earlier, Vedas are apaurusheya, and not subject to any of the limitations of human intellect.

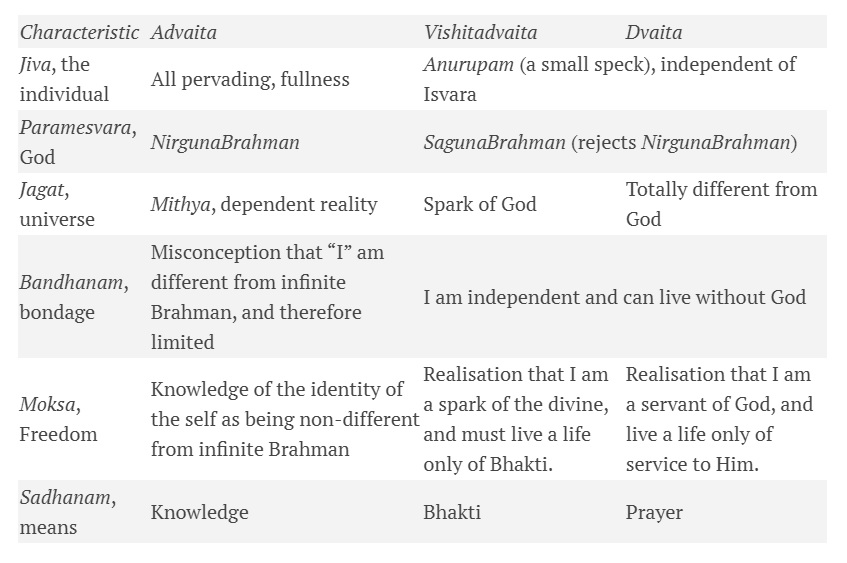

Advaita, Vishitadvaita and Dvaita

All three darshans derive from the prasthanatryaya – Upanisads, Bhagawad Gita and Brahma Sutra. All three consider Vedanta as the prime source of knowledge. They also accept the existence of an unchanging Brahman as both thematerial and efficient cause for jagat, the universe. All 3 subscribe to the Law of Karma and that each individual creates his/her own karma and therefore, karmaphala. They also accept reincarnation, the repeating cycle of birth and death and that the ultimate aim of humans is to find freedom from this cycle, called moksa. Despite these commonalities, there are enough differences between them for the followers of each darshan to be unwaveringly committed to that way of thinking.

For a serious seeker, this poses a serious problem of which one to follow. If he follows any one, it would appear that he has to reject the other two, they being mutually exclusive on many important parameters.

Advaita

Advaita postulates the idea of an unchanging nirguna Brahman, not available to the senses for objectification, and not limited by time or space (since these, along with the material world, also arise from Brahman) as the only reality. There is, however, a saguna Brahman, one with attributes, who becomes the personal God (Istadevata) of religion, and the creator of the entire universe of living and non-living beings. This universe is constantly changing and moving, as against the unchanging Brahman. All of these are, however, seen as dependent reality, called mithya. These arise from upadhi (that which makes a thing appear to be different and limited)[7], called maya. Just as a coloured cloth placed near a crystal imparts (as though) its colour to the crystal, thus limiting the presence of other colours.

In Advaita thinking, the objective is remove this confusion and identify the real nature of the jiva (individual), the jagat and Isvara as being satcitananda Brahman. Therefore, the process to follow is to gain clarity of this knowledge of oneness. Till such clarity emerges, the individual jiva keeps within the cycle of samsara, one of repeated birth and death.

This is an unbroken tradition of Advaita (often called unqualified monism in English), going back to Sadasiva. Advaita proclaims, एकमेवाद्वितीयम्, ekamevadvitiyam. Brahman is the only one, without a second. In the 7th and 8th century CE, Sri Adi Sankaracharya took it upon himself to propagate this vision to counter some nastika traditions that had begun to spring roots in India.

Vishitadvaita

A key statement in Vishista is that Man is a spark of God, Lord Narayana. Made popular by Shri Ramanujacharya in the 11th century, this line of thinking is somewhat like Advaita, but with some additional characteristics. Vishitadvaita propounds that while God, Naryana is one, individual jivatmas are amsa, parts of Narayana, the amsi. Vishitadvaita says that there is unity between individual souls and each can hope for moksa is to “merge” with Narayana or Srinivasa.

SagunaBrahman and the material world, called prakriti, are both real. The sadhana, effort required to attain moksa is in being a bhakta, a devotee, constantly remembering and singing praises of Narayana. It also talks of five kinds of moksa – salokya, arriving at the Lord’s loka, place of residence, samipya, being near Narayana, sarupya, of the same form as God, sarsti, with the same opulence as God Himself,, and Sayujya, merging into Godhood.

However, the individual jiva never becomes one with God. The relationship is described variously as amsa-amsin, shisha-sheshin, sharira-sharirin meaning one is a part of God, will remain so, but never become God Himself.

Dvaita

Madhavacharya (13th/14th Century CE), the proponent of Dvaitam rejects the unity of individual souls, and thus stands opposed to both the other interpretations. The way of thinking of the dvaitin is that these separate individual jivas are also separate from Brahman, Vishnu. Thus, the thinking is in terms of strict dualism. They also propound that the jagat, universe is real, and different from the souls and from God (Narayana)

Moksa is only through the blessing of Narayana, and our purpose is to serve Him as dasa, servant. Therefore, the marga, or path one has to follow is one of total devotion to Vishnu. Vishnu is sagunaBrahman. There is no nirgunaBrahman.

Interestingly, both Ramanujacharya and Madhavacharya started their learning under Advaita gurus. Ramanujacharya’s initial teacher is Yadava Prakasha, an advaitin. It is said he disagreed with his guru and went on to become the chief proponent of Vishitadvaita. Madhavacharya studied under an Advaita guru, Achyutprakashaji in Gujerat, but broke away and started Dvaita interpretation of the Prasthanathraya.

A comparison

What path should a seeker follow?

Despite the differences, all three advocate acceptance of Isvara, and seeking His grace. A good starting point, therefore, for a seeker is to lead a prayerful life, choosing one’s own istadevata, Divinity of choice. At a later stage of progress, when one becomes a serious seeker, one can examine these and pray that Isvara will show them the path. If one starts the process of seeking by arguing about which one to follow, it would be never-ending. Arguments have been going on for centuries and will possibly continue well into the future. Followers of each are unlikely to be convinced to change his/her thinking or life. Therefore, start praying!

Advaitins say one cannot understand the nature of the self without understanding Dvaita. In fact, Advaita is not arrived at by rejecting Dvaita, but in spite of Dvaita. Without recourse to sagunaBrahman, it is not possible to understand nirgunaBrahman. According to the Advaitin, the other two ways of thinking are means to Advaita, not the human end.

According to some commentators, most astikas start by following Dvaitam, a smaller number follow Vishsistadvaitam and an even smaller set is able to move on to Advaitam.

Notes and References

[1]पराञ्चि खानि व्यतृणत्स्वयम्भूः तस्मात्पराङ्पश्यति नान्तरात्मन्।कश्चिद्धीरः प्रत्यगात्मानमैक्षत् आवृत्तचक्षुरमृतत्वमिच्छन्॥ २ १ १ (kathopanisad)

[2]…गुरुमेवाभिगच्छेत् समित्पाणिः श्रोत्रियं ब्रह्मनिष्ठम्॥ १ २ १२ (Mundakopanisad)

[3] Through repeated श्रवण मनन निदिध्यासन

[4]नैषा तर्केण मतिरापनेया। १ २ ९ (kathopanisad)

[5]गुरुवेदान्तवाक्येषु विश्वासः श्रद्धा। Pancadashi

[6]तद्विद्धि प्रणिपातेन परिप्रश्नेने सेवया। Bhagawad Gita 4:34

[7]उपसमीपे स्थित्वा स्वीयान् गुणान् अन्यत्र आदधाति इति उपाधिः। Being near, upadhi (as though) transfers it’s properties to the original object.

Featured Image: Perimeter Institure

(This article was published by IndiaFacts in 2018)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.