A jubilant celebratory air gripped the nation as the arduous wait of five centuries was finally over. Lord Rama is resurgently back in his abode at Ayodhya after a resilient battle culminating in a grand consecration of the splendidly carved vigraha of Ramlalla.

The construction of the Rama Mandira in Ayodhya is a civilizational reclamation that reaffirms the belief of a billion people. It is a cultural resurgence that assigns a new social identity to its masses as a people belonging to the land of Rama, and sets stage for some real social integration and stirs hope for restoring temples to their ancient glory. Much water has flown down questioning the relevance and need for a temple, and what better occasion than this to reiterate to the world the true essence of a temple and their significant contributions as educational and socio-cultural centers that shaped the philosophical mold of the masses and built a society rooted in indigenous ethos.

Temple Culture and Education

Temples in ancient India have played a pivotal role in the spread of education and economic growth of cities and towns where they were located. As a matter of fact, cities and towns grew around the temple. We learn from numerous temple inscriptions about various land and revenue grants made for the purpose of education and learning. Imparting knowledge was highly valued and received patronization from kings, chiefs, the wealthy and the society at large. Revenues of several villages were dedicated for supporting learning and teaching in Ghatikas, Brahmapuris, Agraharas, Mathas. While Temples facilitated imparting of education, the mathas or monasteries served as boarding houses attached to temple schools. Noteworthy among them were the mathas run by Kaalamukhas that became conspicuous from the 11th century onwards. The Kaalamukhas were Saivite teachers belonging to the Pasupatha sect who came from Kashmir and were instrumental in the spread of education in the South and across the country by establishing numerous temples and mathas. The Kodiyamatha at Balligave (Karnataka) attached to the Kedareshwara temple was an important Kaalamukha matha that received royal grants. The temple itself came to be known as Kedara-Matha or Kedara-Sthana. Inscriptions reveal that it was a thriving center of education and charity that provided free education, boarding and lodging to students, teachers and artists. It provided teaching in all branches of learning and was visited by ascetics from far off regions. It also gave shelter to many sections of society, fed the poor and the destitute and arranged for the security and medical facilities of all its visitors. These temple-attached educational universities of ancient times also provided medical facilities as they were equipped with beds, vaidyas, and herbal medicines etc. The Kodiya matha had under its jurisdiction several other minor mathas that were attached to other temples in the vicinity such as the minor matha attached to the Nakareshwara temple at Tavarekere, the Bhujangadevara matha at Tripurantaka temple, the Bonteyadevara matha in Hombala, the Someshwara matha at Brahmeshwara temple at Ablur and the Kriya-Shakti matha dedicated to SarveshwaraShaktiDeva that had seventy-seven temples attached to it. Thus, there existed numerous such important Kaalamukha mathas at Kuppatur, Sudi, Huli, Muttage and SriSaila that were attached to temple schools. This is just one of the many examples of temple attached schools as most of us are usually familiar with only the very popular Nalanda, Takshashila, Odantapuri, Vallabi, Kanchi universities of ancient India. But there existed temple attached schools in every village across the country that provided basic education and many more temple attached universities for higher education that find mention in inscriptional records.

These schools taught Vedas, Puranas, Shastras, reading, writing, reciting, sciences, arithmetic, grammar, literature, prosody, rhetoric, languages, scripts, fine arts, astrology and yoga. Apart from Swadhyaya (self-studies), Adhyapana (teaching) and Vyaakyana (discourse) some mathas even provided vocational training in different skills. This tradition of association of the mathas to temples can still be seen in the Sringeri matha that is associated with the Sharada temple, the Ashtamathas attached to the Udupi Shree Krishna temple, the Yathirajamatha attached to the Melukote Tiru-Narayana temple. These mathas today run few Gurukulas and with time have also adopted modern education and have established educational institutions albeit on a small scale but impart value-based quality education to financially backward class of rural society without any aid from the Government, unlike the royal patronage received in ancient times. The Basadi and Jaina mathas attached to Sravana Belagola and Humcha temple, the Adi-chunichanagiri matha of the Natha Siddha tradition attached to the Bhairava temple, the Siddagangeshwara temple attached to the Virashaiva matha are some more examples of the continuance of the ancient tradition of temple attached schools that are reminiscent of our ancient traditions of upholding the importance of imparting education, although few of these prominent mathas today enjoy more political clout than the others and receive enormous funding through sectarian political support.

However, education in ancient India was aimed at truth and character building of the student who was the upholder of knowledge and cultural continuity. Vidyaadhaana was considered as more meritorious than pilgrimage to a sacred place hence education was imparted free of cost at these temples and mathas. The concept of free education and free meals to school children initiated by modern Governments are vestiges of the ancient Indian education system, only that they have been hijacked by caste politics and no longer serve the essence of education for building integrated societies guided by ethical philosophies and practical sciences.

Temple Economy

All is not lost, as despite the new variations and adaptations, temples have stood the test of time and reiterate their significant position as institutions that can attract tens of thousands of teeming devotees and can significantly aid in churning an integrated society. They bear the promising potential of reemerging as centers of learning, culture, economy and infrastructural development. The massive congregation of millions during the Kumbh Mela and its enormous revenue earnings meshed with the smart city project of Prayagaraj is testimony to the economic and developmental potential that gets created owing to the ritualistic traditions of temple goers. Such a model of leveraging the economic and developmental potential of large temples has been adopted by most state Governments that control the temples and the Ayodhya temple seems to be no exception. Thus, when colossal revenues collected from the communal beliefs and traditions are employed for the secular state, it cannot be that only the economic and tourism potential of temples are deemed relevant while its philosophical and traditional education are cast aside as irrelevant without vetting it.

Our ancestors built educational universities that were attached to temples. We find numerous inscriptions in Southern India that throw light on prominent ancient universities, such as the Ennaiyiram and Kanchi in Tamil Nadu, Naagai and Taalagunda in Karnataka etc. that provide details of these universities that were attached to temples.

The Ghatikas, Agraharas, Brahmapuris, Gurukulas, Vidyapeetas, Mathas, and temples were centers of higher learning and received generous endowments from the state and society. These centers of higher learning imparted education on 4 – 18 subjects. The four major subjects comprised the Anvishaki which dealt with philosophical speculations, Trayi (the three Vedas of Rik, Yajur and Sama), Vartha (Economics that dealt with subjects like agriculture, cattle-rearing, trade and practical training), and Dandaniti or politics dealt with science and art of governance, administration, and warfare. The fourteen Vidyas were – (i) The four Vedas, (ii) Shat-Vedangas (six limbs of Vedas) – Siksha (phonetics), Kalpa (rituals manual), Nirukta (etymology of difficult words in the Vedas), Chandus (prosody), Vyakarna (grammar) and Jyotisha (astronomy), (iii) Puranas and Itihasa (History), (iv) Tarka (logic), (v) Mimamsa (philosophy), and (vi) Dharmashastra (law). Some additional subjects were Ayurveda (medicine), Dhanurveda (military sciences), Gandarvaveda (music) and Arthashastra (statecraft/administration) etc. were also taught.

A continuation of this glorious tradition of imparting traditional educational values through temple schools with a mix of modern learning would be a civilizational reclamation in its true sense.

The Role of Temples

These centers of learning played an important role in administration and upkeep of the society as they were instrumental in instilling morals for ethical conduct and honesty among the people and infused a sense of social responsibility in the society at large.

Temples received rich endowments from kings, chiefs and the wealthy in the form of land grants and revenue grants. The many festivals and fairs of the temple created opportunities for brisk business for traders from nearby villages. It was a source of revenue for the temple and the local administration. The temple also provided employment opportunities for artists and craftsmen. Thus, Temples were public institutions with religious and administrative functions that were owned by the community and consisted of elaborate administrative machinery. It was managed by temple superintendents called Sthanakas or Dharma-darshis. Few big temples had its own elected or nominated administrative council called the Sabha that looked after the temple administration which encompassed the overall functioning of the temple, managing temple revenues, its collection, maintenance of temple land, guarding of temple funds, jewels, articles, supervision of temple functionaries and checking against any appropriation of temple land or misuse of temple funds. These temple administrators were called Dharma-Darshis, who were mostly prominent members of the village, sometimes the local ruler or the headman of the village called gavunda managed the temple administration. Some temples were managed by hereditary Sthanikas or Sthanapathis who were resident heads who oversaw the appropriate functioning of the temple affairs, ensured worship procedures as per customs and scriptural prescriptions and headed the monastic educational institutions called ghatikasthana that was attached to the temple. However, they did not have absolute authority as the ruler of the region was the ultimate authority but he rarely interfered with the religion and administration of temples, temples were in fact tax free (sarvamanya) and self-governed.

Thus, Temples were pivotal hubs of socio-cultural, socio-economic, philosophical and educational activities that created ethical compliance, economic and entrepreneurial opportunities, furthered trade and employment leading to prosperous communities where all members of society from all varnas benefitted. It fed the needy and destitute, created avenues of livelihood, provided medical facilities and undertook to upskill people by offering vocational training at times, encouraged art and the artist. Temples encompassed not just spiritual activities but also administrative activities and even advised the king in his policies as they represented the society at large. Back then the social and the spiritual were interspersed that set the stage for ethical practices and economic prosperity. Today the temple as a public institution has lost its broader scope of independent functioning and is exploited for its revenue collections. But despite its contributions, we are still surrounded by the cacophony questioning the relevance and the need for the establishment of a temple. We have heard advocacies instead for the establishment of hospitals or schools or IITs, in place of a temple. But amidst such rhetoric, the truth is that our temples were indeed centers of learning and knowledge. They were all encompassing institutions that undertook to uplift the self (within) and the society (external) and produced a harmonious integrated society where knowledge, skill and righteousness was placed on high pedestal, trade and commerce was facilitated resulting in economic prosperity, educational excellence and ethical temper.

The Shift in Temple Administration

Temple administration first saw a change in 1788 when Tipu Sultan, the then ruler of the erstwhile state of Mysore issued an order to resume temple endowment lands, sparing few that were supported by Husur Sanads. He appointed Amildars and taluk officials under the supervision of Fouzdars to manage temples. With these changes, the Sabha (temple committee) and the Sthanika (temple manager) lost their powers and had no say in the temple management. Today these Sthanikas serve as helpers in ritual worship. New rules were laid down and a new designation called ‘Parupatthegara’ was created. This new official was appointed to supervise and manage temple affairs systematically under the Amildar. The new rules enumerated the properties of the temple and brought the temple treasury under complete state control for safeguarding them. It is interesting to note that this word ‘parupathya’ in the Kannada language colloquially is still used as a connotation for ‘interference’ or ‘mismanagement’. After Tipu’s death, the British took control of the state, and brought temple management under their control and officially named it Muzarai. Under the British, temple management was reorganized and came under the direct charge of the citizen committees, then later under the British commissioner, that was passed in the hands of the superintendents of the division, then to the Muzarai officials and finally in 1904 the Muzarai department was officially formed. In 1927 the Mysore Religious and Charitable Institution Act was passed which brought the temple management directly under the Government that began to exercise control on both the religious and administrative affairs of the temple through its officers and appointees. Thus, temple management passed from the hands of Sthanakarthas or Sthanacharyas to the State completely.

It is not the scope of this article to discuss about whether or not temples should be under Government control but simply to put forth the prominent role played by the temples as socio-economic, cultural and educational centers; and to reiterate the significant contribution of the temple managers who enabled temples as knowledge centers, that nurtured arts, crafts, sciences, philosophy and imbued ethical values in the people, provided the platform for trade and commerce leading to interactive and prosperous communities and built an integrated society. The Sthanacharyas or Sthanikas or Sthanakarthas as they were known was a distinct designation other than the temple priest who devoted their lives for the temple. They were resident temple heads who were well versed in Vedas, Shastras and Agamas and adept in temple administration. They managed the temple rituals, fairs, and festivals, supervised the temple funds, revenue collections, maintained temple lands, controlled the farmers, ensured smooth functioning of temple schools, provisioned for the food and lodging of pilgrims, students, teachers, and the needy, encouraged arts, crafts, artists, craftsmen.

Hence it is immaterial as to who manages the temple as what is more important is if modern day temples are managed with the same intent and extend the same scope as their ancient counterparts. This requires an administrative machinery with a mix of society and state and a complete reorientation in our understanding of a temple to revive the true essence of a temple which in ancient times not only encompassed ritual worship, spirituality, devotion, but was also instrumental, incidentally or intentionally, in building an integrated society. It kept the civilizational memory alive while setting standards of ethical values, imparting knowledge and skills, creating educational excellence, and brewing economic opportunities. In short, temples established a socio-cultural and socio-economic order in the society on the foundation of righteousness or Dharma. The Sanatani religion has always been about upholding Dharma in this worldly life. Sri Rama and Sri Krishna are worshipped in this land for upholding Dharma and subduing Adharma.

It is in this context that the consecration of the Baala Raamavigraha in Ayodhya is symbolic of seeking protection, prosperity and presence of Rama in all our makings. Shree Rama lives in the cultural consciousness and civilizational memory of this land from eons across the Yugas. Rama is celebrated as ‘Maryada Purushottama’ for his high virtuous character, for his righteous administration and for establishing a socio-political order that was based on Dharma. The consecration of Ramalallavigraha is to the millions of common devotees, a symbolic hope of re-establishing a Dharmic order. A Rama Rajya is certainly farfetched in the modern context but isn’t it true that Rama continues to be venerated for the ideal society he built and the ideal values he stood for, that are still held as worthy of emulation across the Indian subcontinent. So clearly, religion or Dharma in the Indian context is not only about seeking peace and prosperity by making offerings through rituals and worship but also entails establishment of a social order that is rooted in the civilizational ethos of Sarve Janaa Sukhino Bhavantu. And this seamless social order that led Bharata to great heights was made possible through its robust network of educational system comprising of various types of Gurukulas, Paatshalas and industrious guild schools that were aligned with the temple culture. Restoring this alignment of modern education with the traditional roots and re-establishing temples as centers of knowledge would be a reclamation in its true sense that would resonate with Rama’s ideal tenets.

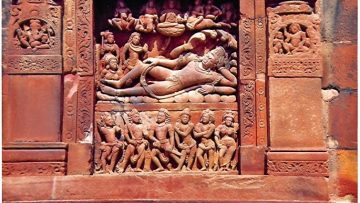

Feature Image Credit: youtube.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.