Introduction

The Vedas stand apart from all other bodies of knowledge. They are apauruṣeya—not authored by human hands, but directly “seen” by ancient ṛṣis in states of profound meditation. What they received was revelation, not composition; timeless truth, not temporal invention. As Śabda-Brahman—the Primordial Sound personified as Veda-Puruṣa—the Veda embodies purity and authority, serving as an independent source of knowledge (pramāṇa).

Yet once truth assumes the form of śabda, it becomes vulnerable. Yāska warns: शब्दानामसंप्रदाने न शास्त्रस्य गतिः। (śabdānām asampradāne na śāstrasya gatiḥ)—without exact transmission of sound, the śāstra cannot endure. Even a minor slip in syllable, accent, or rhythm can distort meaning and weaken continuity. The Veda, however, is not left unguarded.

This essay views the Vedāṅgas as the Veda’s self-born limbs, upholding the continuity of śabda-pramāṇa. Envisioned as a living organism—the Puruṣa—the Veda naturally gives rise to these limbs: Śikṣā preserves sound, Chandas sustains rhythm, Vyākaraṇa guards word-forms, Nirukta anchors meaning, Jyotiṣa aligns recitation with cosmic order, and Kalpa shapes life in harmony with ṛta.

These are not later add-ons but intrinsic guardrails—a kind of oral architecture ensuring that the eternal Veda remains whole and living across millennia.

Śabda as Pramāṇa

In the Hindu tradition, a pramāṇa is a valid means of knowing truth. Some truths come through pratyakṣa (direct perception by the senses), others through anumāna (inference by reason). Yet the deepest realities—dharma, mokṣa, the nature of the Self—lie beyond sense and reason. For these, the tradition turns to śabda-pramāṇa, the authority of the Veda.

The Veda is apauruṣeya—not the work of any human author, but revealed (śruti) to the ṛṣis in states of profound meditation. Free from human error and limitation, it shines by its own light. This view is upheld across the six darśanas—the classical schools of Vedic philosophy—each affirming śabda as a reliable and sacred means of knowing. Mīmāṁsā affirms: apramāṇatvāt puruṣavākyasya—human words are not final authorities. Nyāya declares simply: आप्तोपदेशः शब्दः (“Āptopadeśaḥ śabdaḥ”)—verbal testimony is a valid source of knowing. What sets the Veda apart is its timelessness and authorlessness, revealing truths no eye can see and no logic can deduce.

A verse explains:

प्रत्यक्षेणानुमित्यावा यस्तुपायो न बुध्यते ।

एतं विदन्ति वेदेन तस्माद् वेदस्य वेदता ॥

pratyakṣeṇānumityā vā yastupāyo na budhyate |

etaṁ vidanti vedena tasmād vedasya vedatā ||

(“That which cannot be known through perception or inference is revealed by the Veda. Thus, it is rightly called Veda—‘that which reveals.’”)

Like a mirror that lets the eye see itself, the Veda allows the mind to glimpse its own source. Śabda is not blind authority—it is a guide that must be reasoned with (yukti) and realized in experience (anubhava). As Ādi Śaṅkara put it, युक्त्यनुभवोपपन्नः शब्दः प्रमाणम्। (yukti-anubhava-upapannaḥ śabdaḥ pramāṇam)—śabda is valid when it resonates with reason and is confirmed in lived realization.

Yet for śabda to function as pramāṇa, it must be transmitted with unbroken fidelity. A misplaced syllable or broken metre could distort meaning. To guard against this, the Veda itself gave rise to its six Vedāṅgas—the “limbs” that preserve sound, rhythm, structure, and practice.

Here lies the genius of the Veda’s oral architecture: revelation safeguarded itself. The Veda not only revealed eternal truths, it also embodied the means to preserve them. Śabda-pramāṇa and its preservation are inseparable—like flame and light, they endure together as truth and transmission.

The Veda-Puruṣa and Integration of Vedāṅgas

Tradition envisions the Veda as a Puruṣa —a living, integrated whole. Its limbs embody the seamless integration of sound, rhythm, meaning, time, and practice. This is not just a metaphor—it reflects the Veda’s organic unity. The Vedāṅgas are not external tools but intrinsic aṅgas, naturally arising to safeguard and sustain the Veda. Rather than later additions, these are latent structures brought to full articulation by Maharṣis like Pāṇini, Yāska, Piṅgala, Lagadha, and Āpastamba.

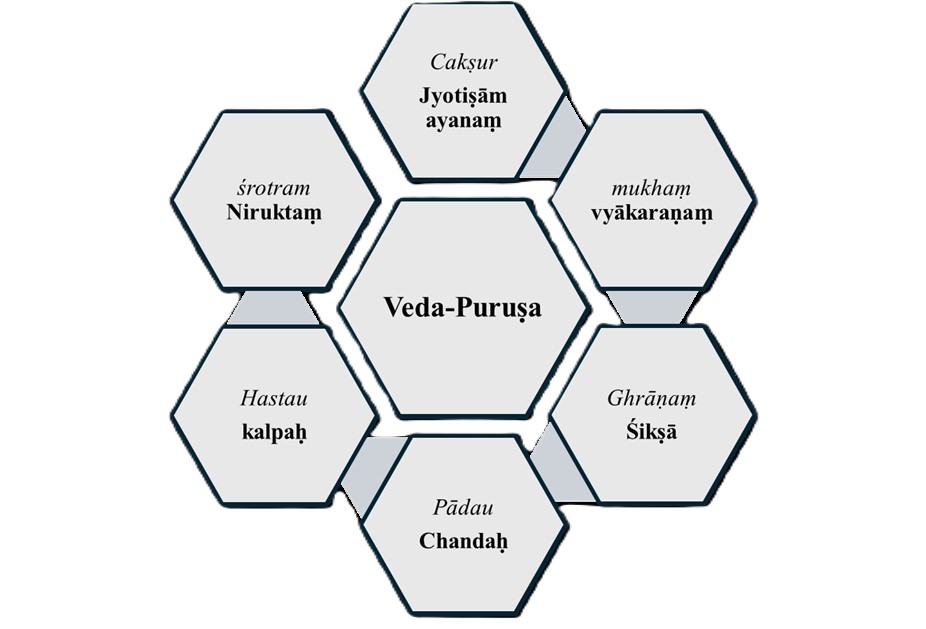

This mapping of the Vedāṅgas to the limbs of the Veda-Puruṣa is affirmed in tradition. Pāṇini’s Śikṣā-sūtra declares:

छन्दः पादौ तु वेदस्य हस्तौ कल्पोऽथ पठ्यते।

ज्योतिषामयनं चक्षुर्निरुक्तं श्रोत्रमुच्यते॥ 41॥

शिक्षाघ्राणं तु वेदस्य मुखं व्याकरणं स्मृतम्।

तस्मात्साङ्गमधीत्यैव ब्रह्मलोके महीयते॥ 42॥

Chandaḥ pādau tu vedasya hastau kalpo ’tha paṭhyate

Jyotiṣām ayanaṃ cakṣur niruktaṃ śrotram ucyate. (41)

Śikṣā ghrāṇaṃ tu vedasya mukhaṃ vyākaraṇaṃ smṛtam

Tasmāt sāṅgam adhītyaiva brahmaloke mahīyate. (42)

A verse from Pāṇini’s Śikṣā-sūtra expresses this beautifully:

(“Metre is the feet of the Veda, Kalpa its hands; Jyotiṣa its eyes, Nirukta its ears; Śikṣā the nose, and Vyākaraṇa the mouth. Therefore, one who studies the Veda together with its limbs is revered in the realm of Brahman.”)

This mapping is also illustrated in the following diagram, where the Veda is personified as a Puruṣa and each Vedāṅga corresponds to a bodily limb—affirming their organic integration and functional unity.

(Figure 1: Veda-Puruṣa and the six Vedāṅgas, each safeguarding a vital dimension(s) of śabda.)

Each Vedāṅga safeguards a vital dimension of śabda:

- Śikṣā ensures purity of sound.

- Chandas sustains rhythm.

- Vyākaraṇa maintains grammatical integrity.

- Nirukta clarifies meaning.

- Jyotiṣa situates recitation in cosmic time.

- Kalpa translates revealed order into lived practice.

Together, they create a seamless oral architecture that safeguards the Veda.

This is the philosophical brilliance of the Veda—it not only reveals eternal truth, but also embodies the means of its own continuity. Unlike systems that rely on external validation, the Veda is self-sustaining. To speak of it as Puruṣa is to acknowledge this organic integration, where the Vedāṅgas ensure that śabda-pramāṇa remains an unbroken authority across time.

The Vedāṅgas as Guardians of the Eternal Word

Each Vedāṅga plays a distinct role in preserving the Veda’s authority as śabda-pramāṇa. We begin with Śikṣā, the discipline that safeguards the purity and power of sound itself.

Śikṣā: The Discipline of Sound

Śikṣā, the first Vedāṅga, safeguards the continuity of śabda-pramāṇa—the authority of sound. The Śikṣāvallī of the Taittirīya Upaniṣad outlines six foundational aspects of sound:

शिक्षां व्याख्यास्यामः । वर्णः स्वरः मात्रा बलं साम सन्तानः ॥

śikṣāṃ vyākhyāsyāmaḥ | varṇaḥ svaraḥ mātrā balam sāma santānaḥ

(“We now explain Śikṣā: varṇa, svara, mātrā, balam, sāma, santāna.”)

Each of these six elements protects a vital dimension of Vedic sound:

- Varṇa (Unit of Sound): Each varṇa is a distinct sound, articulated from its proper region — kaṇṭhya (guttural), tālavya (palatal), mūrdhanya (retroflex), dantya (dental), oṣṭhya (labial), and anunāsika (nasal). Correct articulation preserves the purity of every sound, safeguarding śruti

- Svara (Tone / Accent): The accents — udātta, anudātta, svarita, dīrgha-svarita — carry meaning and ritual potency. Śikṣā ensures each syllable retains its natural contour, preserving rhythm and efficacy.

- Mātrā (Duration of Sound-Units): Syllables — hrasva (short), dīrgha (long), pluta (extended) — maintain rhythm and memorization. Correct duration ensures recitation flows as an unbroken current of revelation.

- Balam (Strength of Articulation): The force of utterance links breath, voice, and meaning. Balanced articulation ensures clarity, resonance, and enlivening of mantra.

- Sāma (Melodic Contour): Melody integrates sounds with recitation. Precise modulation preserves comprehension and the transformative potency of the Veda.

- Santāna (Continuity): Seamless flow, guided by junction rules (sandhi), maintains harmonic coherence across recitations, ensuring the Veda remains a living sound-stream.

Together, they form a self-sustaining architecture of sound, ensuring the Veda remains vibrant and authoritative across generations. They arise naturally from the Veda itself, preserving the eternal sound and its authority across generations.

Chandas: Regulating Metre and Rhythm

Chandas safeguards the Veda through its metrical architecture, with each verse—Gāyatrī, Anuṣṭubh, Triṣṭubh, Jagati—defined by syllabic precision and imbued with spiritual rhythm. These patterns act as self-regulating mechanisms, preventing deviations in oral transmission.

The sequence of pādas (metrical feet) and syllabic lengths (Hrasva, Dīrgha, Pluta) embeds natural redundancy, reinforcing recitation stability. This rhythmic structure integrates sound, time, and memory, allowing the Veda to be transmitted unchanged across generations.

Chandas is not a humanly contrived arrangement but a vision of rhythm discerned by the Ṛṣis. More than formal structure, it is semantic architecture: the cadence of each meter amplifies meaning and spiritual potency. For instance, the Gāyatrī meter embodies cosmic harmony, guiding both comprehension and divine resonance. Rhythm thus safeguards the Veda, ensuring its truth is not only heard but directly experienced.

Through its inherent design, Chandas preserves both sound and meaning—functioning as a living safeguard for śabda-pramāṇa, independent of writing or external aids.

Vyākaraṇa: The Structure of Linguistic Integrity

While Śikṣā preserves the purity of sound, Vyākaraṇa—the science of grammar—safeguards the precision of meaning. It governs how units of sound (varṇa) form words (padāni), and how words combine into coherent sentences (vākya), enabling precise comprehension. As one of the six Vedāṅgas, Vyākaraṇa is a limb of the Veda itself, providing the structural foundation for composition, interpretation, and faithful transmission. It safeguards semantic clarity and preserves the authority of śabda-pramāṇa across generations.

A succinct declaration from Patañjali’s Mahābhāṣya affirms:

शब्दप्रशासनं व्याकरणम्

śabdapraśāsanam vyākaraṇam

(“Grammar (Vyākaraṇa) reigns over speech as its sovereign.”)

This is not mere rhetorical flourish—it reflects the recognition that linguistic order is intrinsic to the sanctity of the Veda. Vyākaraṇa governs word roots (dhātu), prefixes (upasarga), suffixes (pratyaya), indeclinables (avyaya), compounds (samāsa), and phonetic conjunctions (sandhi), encoding generative rules that prevent distortion and foster memorisation through repeatable, intelligible patterns.

The Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini exemplifies this discipline. Its 3,959 sūtras form a generative system for Sanskrit, designed for oral transmission. Technical markers (anubandhas), compressed phonetic formulas (pratyāhāras), and interpretive principles (paribhāṣā-sūtras) together enable precise articulation and reliable understanding. Pāṇini systematized earlier grammatical insights from Śākaṭāyana, Āpiśali, Śākalya, and Śaunaka, giving form to knowledge already present in Vedic tradition.

Vyākaraṇa operates alongside Śikṣā to preserve the Veda in sound and meaning. Even minor errors—misapplied sandhi, case endings, or declensions—could invert the intended meaning, as in Ṛgveda 1.164.39:

एकं सद्विप्रा बहुधा वदन्त्यग्निं यमं मातरीश्वानमाहुः।

Ekaṁ sad viprā bahudhā vadanty agniṁ yamaṁ mātarīśvānam āhuḥ.

(“Truth is one; the wise speak of it in many ways—as Agni, Yama, Mātariśvan.”)

Without grammatical discipline, “Ekam sad” could become “Ekam asat,” or the scope of “viprā bahudhā vadanti” could be misread, undermining both comprehension and ritual efficacy.

Vyākaraṇa is not an external imposition but an inherent safeguard—woven into the very structure of the Veda to preserve its meaning across millennia. Its rules are woven into the tradition itself, securing the continuity of śabda-pramāṇa through precise linguistic order, memorization, and faithful oral transmission.

Nirukta: The Semantic Foundation of Expression

Nirukta, the Vedāṅga devoted to the study of word meanings, safeguards the clarity and depth of Sanskrit expression. While Śikṣā preserves the purity of sound and Vyākaraṇa maintains grammatical discipline, Nirukta ensures that the meaning of words remains precise and aligned with their purpose (prayojana), whether in the Vedas, śāstras, kāvyas, Darśanas, or technical treatises.

Far from being a reactive safeguard, Nirukta is a structural foundation, designed to preserve semantic integrity from the very beginning. Yāska (c. 600 BCE), in his Nirukta, systematically analyzes words across Sanskrit literature, building upon the earlier lexical tradition of the Nighantu. His work ensures that meaning is never lost or distorted, whether in Vedic recitation, astronomy (Jyotiṣa), medicine (Āyurveda), music, drama (Nāṭyaśāstra), or philosophy (Darśanas).

A prime example is Yāska’s treatment of the word Agni, the very first word of the Ṛgveda (1.1.1):

अग्निं ईळे पुरोहितं यज्ञस्य देवम् ऋत्विजम्

Agniṃ īḷe purohitaṃ yajñasya devam ṛtvijam

(I invoke Agni, the purohita of the yajña, the divine ṛtvij.)

In Nirukta 7.14 (daivata kanda), Yāska explains Agni as arising from the root ag, meaning “to move” or “to lead.” He interprets Agni as the force that carries offerings and knowledge upward, bridging earthly and cosmic realms. Agni is described in three dimensions:

- Terrestrial fire, vital for rituals and the ordering of intellectual life.

- Celestial fire, manifest as solar and cosmic energy.

- Sacrificial fire, which safeguards the continuity of knowledge through oral and textual transmission.

Further, Agni is Vaiśvānara, the universal flame present in all beings, linking ritual, cosmos, and consciousness. Without Nirukta, Agni’s rich conceptual significance might be reduced to mere physical fire, and the profound meanings embedded in Vedic expression could be lost.

Nirukta, therefore, works in harmony with Śikṣā, Vyākaraṇa, and Chandas. Together, these Vedāṅgas ensure that words are not only pronounced and structured correctly but are fully understood, preserving their intended meaning across generations. In this way, Nirukta is a vital pillar of the Veda’s oral architecture, sustaining the Veda not just in sound, but in sense, ensuring that śabda-pramāṇa remains whole and living.

Jyotiṣa: The Temporal Alignment of Sacred Expression

Jyotiṣa, the Vedāṅga devoted to time and celestial order, forms the temporal backbone of Vedic ritual and recitation. In its original context, Jyotiṣa is not merely an observational or predictive science—it ensures that every sacred utterance and ritual act resonates with the rhythms of the cosmos. This alignment is essential, for the efficacy and sanctity of Vedic practice depend on timing as much as on sound and meaning.

In the Vedic worldview, kāla (time) is not a neutral backdrop but a living, sacred force. Correctly timing yajñas, samskāras, or parāyaṇas ensures their harmony with ṛta, the cosmic order. Jyotiṣa guides the purohita in determining the muhūrta (auspicious moment), the phases of the moon, solar movement, and positions of the stars—so that each ritual act is perfectly synchronized with the cosmos.

This Vedāṅga forms a kind of temporal architecture within the larger oral architecture of Vedic knowledge. Just as Chandas structures the sound and rhythm of mantras, Jyotiṣa structures their placement in time. It teaches not only how to chant, but when to chant—embedding each utterance within the choreography of the cosmos.

Such temporal alignment also preserves the integrity of oral transmission. Certain recitations, like Sāma recitations or sūryanamaskāra chants, are anchored to specific solar or lunar positions. Across generations, these fixed time anchors acted as mnemonic and ritual guides—protecting both the words of the mantras and the sacred moments in which they are offered.

By integrating Jyotiṣa into the oral tradition, ancient Indian scholars ensured that time itself became a partner in the transmission of sacred knowledge. It bridges the cyclical rhythms of the cosmos with the memory of human reciters, reinforcing continuity and sustaining the śabda-pramāṇa across countless generations.

Kalpa: The Ritual Laboratory of Vedic Knowledge

Kalpa, one of the six limbs of the Veda, provides the procedural foundation for performing karma according to cosmic order (yajña) and other sacred rites described in the Vedas. While often seen as a manual for ritual performance, Kalpa has a far deeper purpose: it structures the practical application, preservation, and intergenerational transmission of Vedic knowledge.

Rituals guided by Kalpa are not merely ceremonial; they embody knowledge. Each act integrates observational, astronomical, and cognitive disciplines into daily life. For example, Trikāla Sandhyāvandana —the thrice-daily ritual—aligns the practitioner with the rhythms of the sun, moon, and stars. It incorporates the calculation of tithi (lunar day), vāra (weekday), nakṣatra (lunar mansion), karaṇa (half-day lunar phase), and yoga (specific cosmic alignments). These practices are ideally performed outdoors at the liminal moments of sunrise and sunset, when celestial phenomena are visible and the sacred order (ṛta) is most perceptible.

Beyond astronomy, Sandhyāvandana cultivates bodily and mental discipline, combining external (bāhya) and internal (antara) purification. Contemplative exercises rooted in the eightfold path (Aṣṭāṅga Yoga) foster mindfulness, self-restraint, and spiritual awareness. In this sense, Vedic rituals became living laboratories—integrating observation, cosmology, and self-discipline into daily life.

By codifying knowledge within ritual frameworks, Kalpa ensured that the Vedic intellectual heritage remained dynamic, embodied, and experiential, rather than static or abstract. Through Kalpa, every ritual became a medium of learning, a conduit through which sacred knowledge was both lived and preserved across generations.

Conclusion: The Veda as Self-Sustaining Revelation

The six Vedāṅgas—Śikṣā, Chandas, Vyākaraṇa, Nirukta, Jyotiṣa, and Kalpa—are not auxiliary disciplines but integrated limbs of the Veda-Puruṣa, arising organically to safeguard its eternal truths. Each Vedāṅga reinforces the others: Śikṣā preserves the purity of sound, Chandas maintains rhythmic flow, Vyākaraṇa secures grammatical structure, Nirukta ensures semantic clarity, Jyotiṣa aligns recitation with cosmic time, and Kalpa grounds knowledge in embodied ritual practice. Like a body whose limbs sustain one another, they form a living, self-protective organism—an oral architecture in which sound, meaning, rhythm, time, and action cohere seamlessly.

For śabda to function as pramāṇa, its transmission had to endure across millennia. The Veda achieved this through a design unmatched in human history: more than a dozen dimensions of safeguarding were woven into its very fabric—six through Śikṣā (sound, accent, intonation, duration, effort, articulation), three through Vyākaraṇa (structure, derivation, usage), and three through Nirukta (etymology, meaning, interpretation). A single syllable misplaced, a Chandas broken, could obscure meaning; hence each limb arose as an organic safeguard.

This genius of integration reveals that the Veda is both revelation and its own preservation. Validity and continuity are inseparable—two sides of the same śabda-pramāṇa. By studying and honouring the Vedāṅgas, one glimpses how eternal truth can persist undistorted, living across generations, to be heard, practised, and experienced. The Veda is not merely a text—it is a living, self-sustaining Puruṣa, whose limbs carry revelation through time: ever vibrant, ever accessible.

References

- Cardona, George. Pāṇini: His Work and Its Traditions. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1997.

- Gonda, Jan. A History of Indian Literature: Vedic Literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas). Vol. I, Fasc. 1. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1975.

- Rajaram, Pandita. Niruktamu. Hindi commentary by Pandita Rajaram. Translated into Telugu by Dr. Īśvara Varāha Narasiṁhamu. Edited by Prof. Kupaa Venkata Krishna Murti. Hyderabad: Emesco Books, 2024.

- Rao, Yerramilli Ramachandra. Vedanga Jyotishamu (Ṛk, Yajusha Jyotishamulu). Telugu translation. Bhubaneswar: Self-published by the author, 2021.

- Radhakrishnan, S. The Principal Upaniṣads. Including Taittirīya Upaniṣad, Śikṣāvallī 1.1. Delhi: HarperCollins, 1994, 545–546.

- Staal, Frits. Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. London: Penguin Books, 2008.

- Telugu Akademi. Pāṇinīya Aṣṭādhyāyī: Kāśikāvṛtti Sahitam (Prathama, Dvitīya Bhāgamulu). Translated into Telugu by Prof. Ravva Sri Hari. Vols. I–II. Hyderabad: Telugu Akademi, Reprint 2017.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, for his constant guidance and for helping me balance traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives. His support has been invaluable in shaping the direction and depth of this essay.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions, which greatly enhanced the clarity and philosophical precision of the work.

My daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), offered a thoughtful editorial review of the article.

Feature Image Credit: wikipedia

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.