On a serene morning in Bengaluru, my wife Sreelakshmi and I had the privilege of visiting (27th November,2024) Professor Viswanatha Krishnamurthy (1927–2025), popularly known as Prof. VK, a scholar whose life embodied an extraordinary synthesis of mathematics and metaphysics. At the remarkable age of 98, he greeted us with a clarity of mind, warmth, and vitality that immediately impressed anyone present. Since the passing of his beloved wife, Kamala, he had been living quietly with the support of his assistant, Satheesh, while his daughter resided in an adjacent apartment. He welcomed us graciously, insisted we share a cup of coffee, and before we sat down, we prostrated at his feet—a gesture that felt both natural and necessary, for here was a man who had not only scaled the summits of academia but had also immersed himself deeply in the timeless wisdom of Hindu philosophy.

As we settled in, Prof. Krishnamurthy fondly recalled the Navaratri days of earlier years, when he would chant the Lalita Sahasranama during the nine days of devotion—a touching reminder that his intellectual brilliance was always balanced with profound spiritual practice. During those sacred days, he used to chant the Lalita Sahasranama ten times each day, performing archana to the Devi idol that has been in his family home for more than two centuries. The age-old presence of this idol imbued his worship with a deep sense of continuity and devotion, reflecting the timeless spiritual heritage he so dearly upheld.

He then took us to his puja room and showed us this unique idol. We bowed reverently before the Jagadamba—majestic yet endearing in form—feeling the powerful presence of the Divine that seemed to fill the entire space.

His academic journey is a saga in itself. Formerly Deputy Director and Professor of Mathematics at BITS, Pilani for over two decades, he later became Director of the K.K. Birla Academy, New Delhi. His mathematical career, spanning more than half a century, includes a series of widely respected books at all levels. While at Pilani, he emerged as one of the top-ranking academic administrators, playing a pivotal role in the multifarious academic reforms that made BITS a model of innovation in higher education.

Prof. Krishnamurthy’s scholarly pursuits also took him to the University of Illinois, Urbana, and the University of Delaware, Newark, in the United States. His research contributions enriched Functional Analysis, Topology, Combinatorics, and Mathematics Education, and under his guidance, five doctoral students completed their Ph.D.s. His leadership extended far beyond classrooms and research: he served as President of the Indian Mathematical Society, President of the Mathematics Section of the Indian Science Congress Association, Executive Chairman of the Association of Mathematics Teachers of India, as well as National Lecturer and National Fellow of the University Grants Commission. In 1996, he led the Indian team at the International Mathematical Olympiad held in Bombay. His mathematical works include Combinatorics: Theory and Applications, Introduction to Linear Algebra (with co-authors), The Culture, Excitement and Relevance of Mathematics, The Clock of the Night Sky, and the Tamil book What is Mathematics – Through Two Puzzles.

Parallel to this formidable academic career ran a lifelong engagement with Hindu spirituality. Trained in the traditional fashion by his Guru, his father, Sri R. Viswanatha Sastrigal, a scholar and exemplar of the dharmic way of life, Prof. Krishnamurthy grew into an erudite interpreter of Vedanta. His lectures—delivered both in India and the United States—are remembered for their precision, clarity, and ability to appeal to the modern mind. He authored a remarkable body of work on religion and philosophy, including Essentials of Hinduism (1989), Hinduism for the Next Generation (1992), The Ten Commandments of Hinduism (1994), Science and Spirituality: A Vedanta Perception (2002), Gems from the Ocean of Spiritual Hindu Thought (2010), Live Happily the Gita Way (2005), Thoughts of Spiritual Wisdom (2018), and Meet the Ancient Scriptures of Hinduism (2019). Many of his writings remain freely available on his website, www.profvk.com, a treasure trove for seekers.

Recognition followed naturally for his contributions to both mathematics and spirituality. Among his distinctions are the Distinguished Service Award (1995) by the Mathematics Association of India, the Seva Ratna Award (1996) by the Centenarian Trust, Chennai, the Vocational Service Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education (2001) by the Rotary Clubs of Guindy and Chennai Samudra, the Prof. T.T. Award for Excellence (2002), and membership on the Board of Moderators of the prestigious Yahoo Group Advaitin since 2003. More recently, in 2019, he received the Grateful2Gurus Award from the Indic Academy.

As our conversation unfolded in his quiet Bengaluru home, it became clear that Prof. VK represented a rare confluence: the rigor of mathematics, the clarity of a teacher, and the wisdom of a Vedantin. What followed was an illuminating dialogue on Moksha, God, Advaita Bhakti, and the eternal quest for liberation—a dialogue that bridged reason and faith, intellect and devotion, the finite and the infinite.

Our time with Dr. V. Krishnamurthy was a rare glimpse into the mind of a scholar who seamlessly combined deep mathematical insight with profound spiritual wisdom. His reflections on faith, philosophy, and the inner meaning of devotion continue to inspire and guide seekers and learners alike.

Having passed away seven months after our interview in June 2025, attaining Vishnuloka, Dr. VK’s legacy endures through his writings, teachings, and the countless lives he touched. We bid him a heartfelt farewell, with gratitude for the light he shared, and may his soul rest in eternal peace.

As his deep devotion to the centuries-old Devi idol in his home had always fascinated me, I chose to begin the interview with a question on the significance of idol worship…

Respected sir, many people wonder—Is the idol of a deity really the deity itself, or merely a representation?

To answer that, let me begin with an analogy. Idol worship can be compared—though only incompletely—to the flag of an army. For a soldier, the flag is not just cloth; it embodies the honour and spirit of the army. Similarly, for a devotee, the idol is far more than stone or metal.

But the comparison is incomplete, because the idol is not merely symbolic. Through constant worship and the chanting of mantras culled from the scriptures, divinity is actually invoked into the physical frame of the idol. This sacred process, known as prāṇa-pratiṣṭhā, transforms the idol into the very deity.

Now, Hindu thought acknowledges different levels of understanding. From the philosophical perspective of Advaita, there is only one Absolute Truth; everything else is its manifestation. At that level, the idol may be seen as a representation, not the “real thing.”

But from the devotee’s point of view—who seeks to relate to Divinity in name and form—the sanctified idol is indeed the deity itself, carrying as much power as the Absolute. That is why Balaji at Tirupati, Nataraja at Chidambaram, Meenakshi at Madurai, Ranganatha at Srirangam, Jagannath at Puri, Krishna at Udupi, Guruvayurappan at Guruvayoor, or even Venkateswara in Pittsburgh, are not worshipped as symbols. They are revered as living presences.

How does the devotee’s perception of the idol evolve with time and spiritual maturity?

In the beginning, the devotee assumes that the Lord resides in the idol. This is an act of faith. Over time, with the Lord’s grace, that assumption turns into realisation. The devotee comes to see that God truly is present in the idol—and also everywhere.

Thus, what starts as belief or assumption matures into lived experience. This is the esoteric significance of idol worship. The millions who have derived strength, solace, and transformation through temple worship across the centuries stand as living testimony to its truth.

But worship always involves duality: the worshipper and the worshipped. How does Hinduism view this limitation?

Yes, worship implies duality, and it is indeed a step below the non-dual realisation of the Divinity within oneself. Yet Hinduism is profoundly human. It recognises that not everyone can immediately grasp or live in the non-dual awareness of the Absolute.

Therefore, the tradition makes space for all—from those who need concrete forms of God to those who meditate on the formless Reality. The Bhagavad Gita (7:21) affirms that each individual may worship God in whatever form suits his temperament, competence, and stage of evolution.

A devotee may choose an ishta-devatā—a personal deity—and worship it as the Supreme. The same individual may worship an idol at one point in life and at another time meditate directly on the transcendent Reality. This freedom to relate to the Divine in multiple ways is a unique prerogative of every Hindu.

So, is that why Hinduism tolerates different Puranas praising different deities?

Precisely. Hinduism accepts that different scriptures may declare different deities as supreme. The Śiva Purāṇa may extol Śiva as the highest, while the Viṣṇu Purāṇa does the same for Viṣṇu. There is no contradiction here—only an affirmation that the Absolute can be worshipped in countless ways.

This eclecticism sometimes invites criticism that Hinduism is “too tolerant.” But can we say a person is “too rich” or a woman “too beautiful”? Tolerance, diversity, and freedom are the very hallmarks of Hindu spirituality.

Let us move to the spiritual path itself. What do you mean by it?

The spiritual path begins with the understanding that when a living being dies, only the body perishes. The jīva (soul) survives and transmigrates into another body. Along with the jīva travels the subtle mind, which carries impressions from previous lives.

These impressions, called vāsanās, are not memories stored in the brain but tendencies imprinted on the subtle mind. Like the wind that carries fragrance after passing through a rose garden—or stench after passing through filth—the mind carries noble or ignoble tendencies across births. These vāsanās shape the character, instincts, and inclinations of each new life.

Are all vāsanās negative, or do some uplift us?

Not all are negative. Two of the noblest tendencies are śraddhā (faith) and bhakti (devotion with dedication). Faith is the trust in the divinity within us, and devotion is the dedication to that inner Divinity. Together, they form the natural spiritual inclination of humanity.

But these noble tendencies are often overshadowed by what I call the “gang of thirteen”—attachment, hatred, lust, anger, greed, delusion, arrogance, jealousy, self-pity, malice, vanity, pride, and their leader, the ego.

The central challenge of life is to redirect the mind away from these channels toward the channels of faith and devotion. Here free will comes into play. The will is neutral; it can be trained to say to the ego: “E-GO, you go!”

What about virtues like compassion or humility? Where do they fit in sir?

They are consequences of faith and devotion. For example, compassion arises from the faith that other beings are equal to us. Humility arises from devotion to something higher. Similarly, negative emotions like revenge are outcomes of thought-flows in the channels of anger or hatred.

Thus, feelings—good or bad—are consequences of the basic tendencies accumulated over lifetimes. A person who has nurtured compassion and service in past lives may display nobility almost from birth. The vāsanās already channel the mind in that direction.

How does Vedanta define the spiritual path in terms of the mind?

The mind is the meeting point of science, religion, and philosophy. With the mind, man explores nature, seeks solace, and speculates on the mysteries of existence. But the same mind is also man’s greatest enemy, never fully under control.

Vedanta therefore insists on disciplining the mind, even partially. The essence of the spiritual path is precisely this: to restrain the undesirable tendencies of the mind, to strengthen faith and devotion, and to channel one’s will toward the realisation of the Divinity within.

That is the journey from duality to unity, from assumption to realisation, from worship of form to the vision of the formless Absolute.

(Prof. V. Krishnamurthy – the calm radiance of a life steeped in knowledge & devotion.)

According to Hindu scriptures, the ultimate aim of life is moksha—Liberation or Enlightenment. What exactly is Enlightenment? Has anyone living now attained it? And if so, where can we meet them?

Enlightenment, or moksha, is the culmination of the spiritual journey. The Bhagavad Gita (5:18) says: “The sages see with equal vision a learned and cultured Brahmin, a cow, an elephant, a dog, and even an outcast.” This balanced view of everything as One, as the Self, is called Brahmānanda—the bliss of realisation.

This was the continuous experience of sages like Ramana Maharishi, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, and others of that stature. It is not something measurable by external instruments. Rather, it is an inner state of fortitude, equal-mindedness, and serenity, which manifests as profound happiness. At that highest level, categories such as good and bad cease to have meaning.

The qualities of poise, perspective, peace of mind, and patience—what I call the “four Ps”—arise naturally in that state. These are not mere personality traits; they are the very components of lasting happiness. This is it—the ultimate goal of human life.

What do the scriptures say about God in this context?

Hindu Vedanta teaches that God, the Absolute Reality, is both transcendent and immanent. Transcendent, because He—or It—is beyond all finite conceptions. Immanent, because He dwells in every particle of existence.

The Mahanarayanopanishad declares: “Whatever we see, hear, smell, taste, or touch—everything is the Almighty.” And the Bhagavad Gita (7:8–9) affirms: “I am the taste in water, the light in the sun and moon, the sound in space, the fragrance of the earth, the brilliance of fire, the life in all beings.”

It may sound like poetry or music, but that is precisely the point. The universe itself is the song of the Absolute—the dance of the Divine. Saints tell us that such realisation dawns in the state of samādhi.

Can you describe that state of Enlightenment more vividly?

It is best described by those who have lived it. The great saint Kripananda Variyar said: “The sages revel in their equanimous vision and bliss of compassion. They are conscious of nothing but the fullness of Consciousness. In that state there is no ‘I’ or ‘Mine’. The little self merges in the Supreme Self. Knowledge and ignorance both dissolve in oneness. There is no seer, no vision, nothing to be seen.”

In such a state, time and action, merit and sin, pleasure and pain—all lose significance. It is a state full of Grace and Light, beyond darkness and confusion. A massive Light of Consciousness, transcending speech and thought.

Who can describe such a state? Only a realised master like Adi Shankara, who captured it in poetry:

“No merit, no demerit, no happiness, no misery, no chants, no holy waters, no scriptures, no rituals.

I am neither the experiencer, nor the experienced, nor the experience.

I am Consciousness, I am Bliss, I am Shiva.” This is the acme of Enlightenment.

Who can guide humanity toward this path of Liberation?

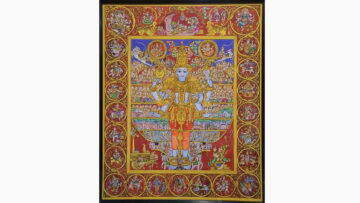

Only such brahma-jnanis—knowers of the Absolute—can authentically point the way. In our own times, we had Ramana Maharishi, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Kanchi Mahaswamigal, and a few others. Though their lives were different, they all affirmed the same truth: this universe is nothing but the Almighty. Recall the opening words of the Vishnu Sahasranama: “Vishvam Vishnuh”—The Universe is Vishnu.

Sir, what is your understanding of God?

Words can never do justice to God. The Upanishads declare: “The eyes cannot see Him. The ears cannot hear Him. The mind cannot think Him. Words cannot express Him.”

He is taller than the tallest, shorter than the shortest. He is not a “He” or “She” in the ordinary sense—He is beyond gender, beyond subject and object, beyond category or quality. That is why the Upanishads often call Him simply It.

Philosophically, we speak of three aspects of God:

- Transcendence – God is beyond time, space, and causation. He is Purushottama—the Supreme Person, yet beyond personhood itself.

- Immanence – God pervades everything. The universe is His concrete expression. He is nearer to us than our own breath, the soul of our souls, the substratum of everything.

- Perfection – God is perfect, symbolised by the image of Nataraja, the Cosmic Dancer. Yet He descends to guide us in the form of an avatāra.

Krishna, for example, is seen as the complete avatāra, though His divine play includes mystery and illusion. Rama, on the other hand, is held up as the model of perfection—a suvrata, one who lived an unswerving life of vows. Rama’s five-fold vrata—to protect all who sought refuge, to obey his parents, to uphold his duties as king, to remain unperturbed in adversity, and never to flaunt his divine stature—makes him the eternal exemplar for humanity.

This, in short, is my understanding of God: Transcendence, Immanence, and Perfection—TIP, as I like to call it. But remember, this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Finally, what is Advaita-Bhakti?

The Maha Periyava of Kanchi put it beautifully. There is no joy in life without love. But human love is always tinged with sorrow, because we are eventually separated from the objects of our affection. The only Being who never leaves us is God.

If we can direct our love exclusively to Him, our happiness becomes everlasting. As this love matures, it transforms into Advaita-bhakti—a love so universal that it sees no high or low, no distinction, no duality. In this state, the entire world is seen as God Himself.

Such love is not wasted, nor does it betray us. Unlike worldly attachments that turn to sorrow, love of God matures into infinite love, embracing all beings equally. This is the culmination of devotion, and the antidote to a loveless human life.

As the midday hours approached, our conversation with Professor V. Krishnamurthy drew to a close. What began as a dialogue soon turned into a satsang, a flowing river of wisdom where insights on moksha, bhakti, and the unfathomable nature of God merged effortlessly with his gentle reminiscences of a life steeped in scholarship and sadhana. Though nearing a century in age, his eyes still sparkled with the clarity of conviction and the quiet glow of inner peace.

With deep reverence, we once again bowed at his feet, feeling blessed to have shared those precious hours in his luminous presence. His devoted assistant Satheesh watched silently, aware of the sacredness of the moment. Before we took leave, Professor Krishnamurthy lovingly handed us a set of books as prasada—tokens of his affection and wisdom. They included Thus Spake Krishna, his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita; Soundaryalahari, translated into English from the original text of Kanchi Paramacharya; his autobiography Looking Back; and Thoughts of Spiritual Wisdom, a compilation of his reflections. Receiving these volumes from him felt like receiving sacred offerings, each book carrying the fragrance of his lifelong devotion to knowledge and the Divine. As we rose to leave, Professor Krishnamurthy smiled warmly, as if sending us off not merely from his home in Bengaluru but from the very sanctum of timeless wisdom. Carrying his words in our hearts, we stepped out with gratitude, knowing that this meeting was not just an interview but a benediction.

(Thoughts of Spiritual Wisdom – A compilation of Prof Krishnamurthy’s reflections)

Through this dialogue, we see that Enlightenment is not an abstraction but a lived reality; God is not distant but both beyond and within us; and Advaita-bhakti is the flowering of love into infinity. These insights, drawn from scripture and saints, continue to guide seekers today toward the highest goal of life—Moksha.

(Editor’s Note: This interview with Professor Viswanatha Krishnamurthy was conducted by Pradeep Krishnan at the Professor’s residence in Bengaluru on 27th November 2024. Unfortunately, before the interview could be completed and published, Professor Krishnamurthy passed away in 2025. Believed to be the last interview he gave to any media, this conversation captures his profound wisdom, humility, and deep commitment to dharmic thought. It stands as a fitting tribute to a remarkable teacher, scholar, and seeker.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.

![“From Pain to Presence: The Journey of Jake Light” [An Interview with Spiritual Master Jacob Shivanand]](https://www.indica.today/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Jecob-Shivanand-article-360x203.jpg)