3.2 The concept of Tridevatā vs. Eastern and Catholic Church

Christian Interlocutor:

We do not affirm three distinct personalities in the manner you suggest, nor three separate beings. The distinction lies in hypostases, not in division of Godhead.

Hindu:

If distinction is admitted at the level of hypostasis, how is unity to be philosophically secured?

Christian Interlocutor:

Unity is grounded in ousia. God is one in essence. The Father, the Son, and the Spirit share the same undivided divine nature.

Christian Interlocutor:

The Father is called supreme only with respect to origin, not essence. He is the source and fountain of the Godhead. The Son is begotten of the Father, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. This order does not imply inequality of nature.

Hindu:

Yet origin itself introduces hierarchy. Cause and effect are not symmetrical relations.

Christian Interlocutor:

There is causal priority, but no ontological superiority. The Father communicates the whole divine essence to the Son. Nothing of divinity is withheld. The Son is eternal, consubstantial, and equal in nature.

Hindu:

Then the cause is not greater than the effect.

Christian Interlocutor:

Correct. This is the paradox the tradition maintains. The Father is the source, yet the Son lacks nothing.

Hindu:

Such a paradox signals an unresolved tension rather than a solution. In both experience and metaphysical reasoning, the cause invariably appears prior and superior to the effect. Equality is preserved here only by suspending ordinary metaphysical intuition.

Christian Interlocutor:

Western theology addresses this tension by grounding unity not in the person of the Father but in the one divine essence itself. God is absolutely simple. The Father, the Son, and the Spirit are not parts or components, but relations subsisting within that single essence.

Hindu:

Yet your own formulation concedes real distinctions. Relations are not nothing. If relations subsist, then multiplicity subsists at some level. Unity is thus maintained verbally, while plurality reappears conceptually. A structurally similar yet philosophically cleaner articulation already exists within Sanātana Dharma in the doctrine of Tridevatā. Here, unity is not preserved by restricting the consequences of distinction, but by grounding distinction entirely within a single reality.

The Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa states:

सत्त्वं रजस्तम इति निर्गुणस्य गुणास्त्रयः ।

स्थितिसर्गनिरोधेषु गृहीता मायया विभोः ॥ (2.5.18)[1]

sattvaṁ rajas tama iti nirguṇasya guṇās trayaḥ |

sthitisarganirodheṣu gṛhītā māyayā vibhoḥ ||

(Although Brahman is nirguṇa, for the purposes of creation, maintenance, and dissolution, the one Reality, through Māyā, assumes the three guṇas: sattva, rajas, and tamas.)

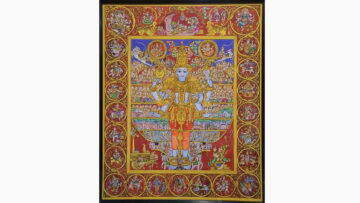

Here, the one Brahman does not stand alongside distinct hypostases as co equal relata. Rather, Brahman alone is the substance, while Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiva represent differentiated functions grounded in that same undivided reality.

This is made explicit again:

अजानतां त्वत्पदवीमनात्मन्यात्मात्मना भासि वितत्य मायाम् ।

सृष्टाविवाहं जगतो विधान इव त्वमेषोऽन्त इव त्रिनेत्रः ॥ (10.14.19)[2]

ajānātāṁ tvatpadavīm anātmaniātmātmanā bhāsi vitatya māyām |

sṛṣṭāv ivāhaṁ jagato vidhāna iva tvam eṣo ’nta iva trinetraḥ ||

(To those ignorant of Your true transcendence, You appear as part of the world through the expansion of Your power. For creation, You appear as Brahmā; for preservation, as Viṣṇu; and for dissolution, as Śiva.)

Thus, unlike Christian Trinitarian models, where unity is preserved by carefully limiting the implications of real relations, Sanātana Dharma grounds plurality entirely within ontological identity. The One does not coexist with distinctions; the distinctions are nothing other than the One itself, appearing through function and manifestation. Unity here is not defended by paradox, but affirmed by metaphysical identity.

3.3 Śrī Rāmānujācārya vs. Swedenborgian Church

Hindu:

Your criticism of plurality applies equally to classical Trinitarianism. If there are three persons, no matter how insistently one speaks of one substance, the mind inevitably conceives three gods. Then how do you preserve monotheism while retaining the Trinity?

Swedenborgian Interlocutor:

By rejecting the notion of three persons altogether. The Trinity exists within the single person of Jesus Christ. The Father is the divine soul, the Son is the divine body, and the Holy Spirit is the divine operation. These are three essentials of one person, not three persons.

Hindu:

This appears closer to unity. Yet how do you account for the biblical distinction between Father and Son, especially in moments such as prayer or suffering?

Swedenborgian Interlocutor:

These reflect an internal process. During His earthly life, Christ possessed a finite human consciousness inherited from Mary and a divine consciousness from the Father. Salvation consisted in the gradual glorification of the human, culminating in full divine embodiment.

Hindu:

As the Gospel says: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (John 1:14)[3]

God the Father has assumed the form of God the Son. Yet a question arises that reason cannot evade. Before this assumption, where was the body which you identify as the Son? And after glorification, when no material body is present, where is this body now? If the body neither existed eternally in the past nor persists now in any intelligible form, then embodiment appears contingent rather than essential.

Swedenborgian Interlocutor:

The difficulty arises from assuming that “body” must mean material extension as understood in temporal nature. In our theology, the divine body of the Son is not flesh as such, but the Divine Human. Prior to the Incarnation, the Divine existed as pure love and wisdom, beyond finite form. In the fullness of time, this Divine assumed a human form in order to become visible, approachable, and redeeming. After glorification, the body was not discarded but fully divinized. It is no longer material, yet it is no less real. The Divine Human now exists eternally as the form of God Himself. Thus, embodiment is not contingent; it is fulfilled. What was implicit becomes explicit, what was invisible becomes manifest.

Hindu:

Your explanation gains coherence by redefining embodiment, yet it also introduces a difficulty. When you say that Father, Son, and Spirit are one in the form of Jesus, unity becomes historically localized. If instead you were to say that they are one in the form of God, the claim would be metaphysically stronger. Otherwise, unity rests upon a particular manifestation rather than upon the divine reality itself.

A closely parallel but more comprehensive doctrine already exists in Hindu philosophy, articulated with precision by Śrī Rāmānujācārya. He does not limit embodiment to a single historical incarnation. Rather, he holds that the entirety of reality is the body of Brahman, while Brahman is the inner Self of all. Thus, embodiment is not assumed at a moment in time, but is eternal and all-pervasive.

Śrī Rāmānuja states in the introduction of Vedānta Dīpa:

सर्वावस्थस्य चिदचिद्वस्तुनः परमात्मशरीरत्वं परमात्मनश्चात्मत्वम्।[4]

Sarvāvasthasya cidacidvastunaḥ paramātmaśarīratvaṃ paramātmanaś ca ātmatvam.

(In all states, sentient and insentient entities are the bodies of the Paramatma, and Paramatma is their soul.)

This establishes an inseparable body-soul relation between Brahman and the universe. Unity is not achieved by denying distinction, but by grounding distinction in absolute dependence.

Śrī Rāmānuja further clarifies:

अचिद्वस्तुनः स्वरूपतः स्वभावतश्चात्यन्तविलक्षणस्तदात्मभूतश्चेतनः प्रत्यगात्मा। तस्माद्बद्धान्मुक्तान्नित्याच्च निखिलहेयप्रत्यनीकतया कल्याणगुणैकतानतया च सर्वावस्थचिदचिद्व्यापकतया धारकतया नियन्तृतया शेषितया चात्यन्तविलक्षणः परमात्मा।[5]

Acidvastunaḥ svarūpataḥ svabhāvataścātyantavilakṣaṇastadātmabhūtaścetanaḥ pratyagātmā. Tasmādbaddhānmuktānnityācca nikhilaheyapratyanīkatayā kalyāṇaguṇaikatānatayā ca sarvāvasthacidacidvyāpakatayā dhārakatayā niyantr̥tayā śeṣitayā cātyantavilakṣaṇaḥ paramātmā.

(The individual self, which is conscious and the inner self of insentient matter, is by nature and essence entirely distinct from matter. Yet the Supreme Self is utterly distinct from bound souls, liberated souls, and eternally liberated souls alike, by virtue of being free from all defects, possessing infinite auspicious qualities, pervading all sentient and insentient entities in every state, sustaining them, governing them, and remaining their absolute Lord.)

Here, unity is not preserved by redefining embodiment or confining it to a single historical figure. Nor is it protected by suspending metaphysical intuition. Rather, unity is secured by identity at the level of reality itself. All plurality is real, yet none is independent. Difference does not threaten oneness, because nothing exists outside Brahman.

In comparison, Swedenborgian theological unity is preserved by collapsing the Trinity into the single historical person of Jesus Christ, thereby resolving plurality through personal concentration. The Hindu model articulated by Śrī Rāmānuja, by contrast, grounds embodiment eternally and universally, not in a contingent incarnation but in the very structure of reality itself. Embodiment is neither episodic nor exclusive, but an abiding metaphysical relation between Brahman as soul and the entire cosmos as body. Unity, therefore, is not secured by restriction to a single form, but by ontological identity that remains constant across all states.

4. Saṅgati

The saṅgati of the foregoing discussion lies in the internal correlation between the positions examined, the scriptural references cited, and the logical principles employed. Each argument is not presented in isolation, but is deliberately situated within a structured progression, where doctrinal claims are tested against both authoritative texts and coherent metaphysical reasoning.

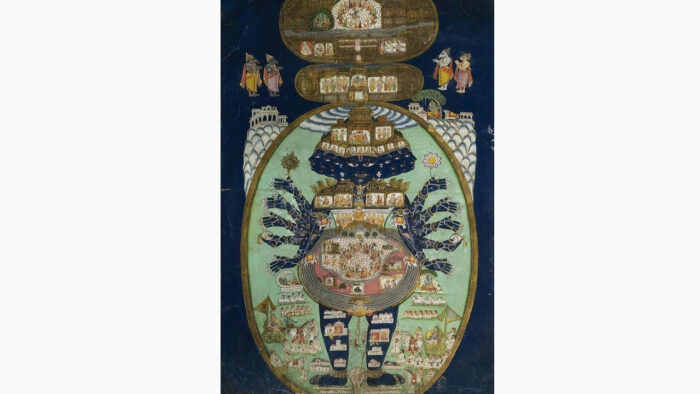

5. Unity of Variegated Devatas in Brahman

Much has already been said about the multiple shades and formulations of monotheism. Yet the Hindu position is often left insufficiently clarified, particularly with regard to how unity is to be understood amid the plurality of deities. The present inquiry does not seek to force Hindu thought into a preexisting monotheistic framework. Rather, it aims to articulate, on its own terms, how the many gods are unified in the one Brahman and in what precise sense this unity is philosophically sustained. Hindu traditions offer diverse accounts of this problem, each grounded in its own metaphysical commitments. In what follows, the discussion will be guided specifically by the doctrine of Śrī Vallabhācārya, whose vision provides a distinctive and internally coherent account of divine unity without dissolving plurality.

At the very beginning, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by Brahman. The Upaniṣads define Brahman succinctly as:

सत्यं ज्ञानमनन्तं ब्रह्म ॥ Taittirīya Upaniṣad, 2.1 ॥[6]

satyam jñānam anantaṃ brahma

(Brahman is that which exists, is self-aware, and is infinite.)

This definition does not describe Brahman through external attributes but through its very being. Satya signifies that which truly exists; jñāna denotes self-luminous awareness rather than acquired knowledge; and ananta indicates infinity. Brahman is thus not one entity among many, but the infinite ground of all existence and the existence itself. It is this very reality that was referred to earlier as existentially infinite, and precisely because of this infinitude, Brahman is capable of manifesting as all Devatās without undergoing division or loss. The Upaniṣads further explain that all Devatās are derived from Him:

यथाऽग्नेः क्षुद्रा विस्फुलिङ्गा व्युच्चरन्त्येवमेवास्मादात्मनः सर्वे प्राणाः सर्वे लोकाः सर्वे देवाः सर्वाणि भूतानि व्युच्चरन्ति ॥ Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, 2.1.20 ॥[7]

yathā’gneḥ kṣudrā visphuliṅgā vyuccaranty evam evāsmād ātmanaḥ sarve prāṇāḥ sarve lokāḥ sarve devāḥ sarvāṇi bhūtāni vyuccaranti

(Just as small sparks issue forth from a blazing fire, so from this Supreme Self arise all sentient beings, all worlds, all gods, and all insentient beings.)

Here, plurality is not portrayed as a rupture within unity but as its natural expression. Sparks are not alien to fire, nor do they diminish it. In the same way, the Devatās emerge from Brahman without compromising its oneness. Multiplicity flows from fullness, not from fragmentation. A question then arises: how can such an abstract reality be perceived? The Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa addresses this:

वदन्ति तत्तत्त्वविदस्तत्त्वं यज्ज्ञानमद्वयम् ।

ब्रह्मेति परमात्मेति भगवानिति शब्द्यते ॥ 1.2.11 ॥[8]

vadanti tat tattva-vidas tattvaṃ yaj jñānam advayam |

brahmeti paramātmeti bhagavān iti śabdyate ||

(Those who know reality speak of the non-dual truth as Brahman, as Paramātmā, and as Bhagavān.)

From the standpoint of Bhagavān, Brahman reciprocates with the devotee, responding to devotion without ceasing to be infinite. The Bhagavad Gītā further explains why such diversity of approach exists:

त्रिविधा भवति श्रद्धा देहिनां सा स्वभावजा।

सात्त्विकी राजसी चैव तामसी चेति तां श्रृणु ॥ 17.2 ॥[9]

trividhā bhavati śraddhā dehināṃ sā svabhāvajā |

sāttvikī rājasī caiva tāmasī ceti tāṃ śṛṇu ||

(The faith of embodied beings is of three kinds, arising from their own nature: sāttvika, rājasa, and tāmasa.)

Faith unfolds according to one’s inner nature (svabhāva). Since individual dispositions are infinitely diverse, the modes of worship and the apprehended forms of the divine also appear manifold. The plurality of Devatās thus mirrors the plurality of seekers, while the object of worship remains one and the same, Brahman. This vision is stated explicitly in the Upaniṣad:

एको देवो बहुधा निविष्ट अजायमानो बहुधा विजायते॥ तमेतमग्निरित्यध्वर्यव उपासते। यजुरित्येष हीदं सर्वं युनक्ति। सामेति छन्दोगाः। एतस्मिन्हीदं सर्वे प्रतिष्ठितम्॥ विषमिति सर्पाः। सर्प इति सर्पविदः। ऊर्गिति देवाः। रयिरिति मनुष्याः। मायेत्यसुराः। स्वधेति पितरः। देवजन इति देवजनविदः। रूपमिति गन्धर्वाः। गन्धर्व इत्यप्सरसः॥ तं यथायथोपासते तथैव भवति। तस्माद् ब्राह्मणः पुरुषरूपं परब्रह्मैवाहमिति भावयेत्। तद्रूपो भवति। य एवं वेद॥

eko devo bahudhā niviṣṭa ajāyamāno bahudhā vijāyate॥tam etam agnir ity adhvaryava upāsate। yajur ity eṣa hīdaṃ sarvaṃ yunakti। sāmeti chāndogāḥ। etasmin hīdaṃ sarve pratiṣṭhitam॥ viṣam iti sarpāḥ। sarpa iti sarpavidaḥ। ūrj iti devāḥ। rayir iti manuṣyāḥ। māyety asurāḥ। svadheti pitaraḥ। devajana iti devajanavidaḥ। rūpam iti gandharvāḥ। gandharva ity apsarasaḥ॥ taṃ yathāyathopāsate tathaiva bhavati। tasmād brāhmaṇaḥ puruṣarūpaṃ parabrahmaivāham iti bhāvayet। tadrūpo bhavati। ya evaṃ veda॥

One Deva alone abides in many ways; unborn, He appears to be born in many forms. Some worship Him as Agni; the Adhvaryus call Him Yajus. The Chāndogas call Him Sāman.

In Him, indeed, all this is firmly established. The serpents call Him poison; the knowers of serpents call Him serpent. The gods call Him vital power (ūrj); humans call Him prosperity (rayi). The Asuras call Him Māyā; the Pitṛs call Him Svadhā. The knowers of divine beings call Him Devajana; the Gandharvas call Him Beauty; the Apsarases call Him Gandharva. As one worships Him, so indeed does one become. Therefore, the knower should contemplate the Supreme Brahman as the Person and as the Self, ‘I am that very Brahman.’ Becoming of that nature, he attains it, he who thus knows.”

(The Upaniṣad does not propose many ultimate realities but one Brahman apprehended through many names, functions, and forms. Diversity of worship arises from diversity of svabhāva; unity is preserved because every form, when rightly understood, refers back to the same non-dual Brahman. Liberation is not granted merely by devotion to a particular deity, but by recognizing that the deity worshipped is none other than Brahman itself. In this way, plurality is harmonized without being negated, and unity is affirmed without erasing difference.)

In the same framework, even Śrī Vallabhācārya also articulates a precise theological hierarchy without denying plurality:

आदिमूर्तिः कृष्ण एव सेव्यः सायुज्यकाम्यया।

निर्गुणा मुक्तिरस्माद्धि सगुणा सान्यसेवया ॥[10]

(tattvārthadīpanibandha, 1.13-13.5)

ādi-mūrtiḥ kṛṣṇa eva sevyaḥ sāyujya-kāmyayā |

nirguṇā muktir asmād dhi saguṇā sānya-sevayā ||

(Kṛṣṇa alone is the primordial form worthy of worship for one who seeks complete union. From Him arises nirguṇa liberation, whereas the worship of other deities leads to saguṇa liberation.)

Here again, unity is not preserved by negating other Devatās but by grounding them in a single original source. Other forms of worship are valid and salvific, yet they yield liberation conditioned by attributes, while devotion to Kṛṣṇa, understood as the complete manifestation of Brahman, leads to unconditioned liberation. Thus, Hindu thought does not protect unity by suppressing plurality, nor does it dissolve plurality into abstraction. Unity is maintained because all forms, all Devatās, and all paths are rooted in one infinite Brahman, who reveals Himself diversely while remaining one without a second.

Following the path articulated by Śrī Vallabhācārya, the discussion now turns naturally toward Śrī Kṛṣṇa as Brahman Himself, not as a manifestation among others, but as the very ground of all manifestation. The Upaniṣadic tradition itself gestures toward this identity when it declares:

कृषिर्भूवाचकः शब्दो णश्च निर्वृतिवाचकः ।

तयोरैक्यं परं ब्रह्म कृष्ण इत्यभिधीयते ॥[11]

(Gopālapūrvatāpinī Upaniṣad, 1)

kṛṣir bhūvācakaḥ śabdo ṇaś ca nirvṛtivācakaḥ |

tayor aikyaṃ paraṃ brahma kṛṣṇa ity abhidhīyate ||

(The syllable kṛṣ denotes existence, while ṇa signifies bliss or infinite freedom. The unity of these two is the Supreme Brahman, which is designated by the name Kṛṣṇa.)

Here, the name Kṛṣṇa is not symbolic or devotional alone; it is metaphysical. Existence (sat) and infinite fullness (ānanda) converge without remainder. The name itself becomes a declaration of Brahman. This insight is reinforced decisively in the Śrīmad Bhāgavata Purāṇa, where all divine manifestations are gathered into a single conclusion:

एते चांशकलाः पुंसः कृष्णस्तु भगवान्स्वयम् ॥ 1.3.28 ॥[12]

ete cāṃśakalāḥ puṃsaḥ kṛṣṇas tu bhagavān svayam ||

(All these are portions or partial manifestations of the Supreme Person, but Kṛṣṇa alone is Bhagavān Himself.)

Thus, unity is not preserved by abstraction, nor by collapsing distinctions through conceptual restraint. It is preserved by identity by recognizing that the source, substance, and fullness of divinity reside wholly in one reality.

This recognition is not confined to later devotional theology. In the Bhagavad Gītā, Arjuna articulates this same realization, grounding it in the authority of revelation, tradition, and direct encounter:

आहुस्त्वामृषयः सर्वे देवर्षिर्नारदस्तथा।

असितो देवलो व्यासः स्वयं चैव ब्रवीषि मे ॥ 10.13 ॥[13]

āhus tvām ṛṣayaḥ sarve devarṣir nāradas tathā |

asito devalo vyāsaḥ svayaṃ caiva bravīṣi me ||

(All the sages proclaim You as the Supreme including the divine sage Nārada, Asita, Devala, and Vyāsa. You Yourself also declare this to me.)

In this vision, plurality does not threaten unity, nor does embodiment compromise transcendence. Kṛṣṇa is not Brahman by adoption or function, but Brahman by nature the one reality appearing as many without ever ceasing to be one.

Feature Image Credit: pinterest.com

[1] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, śrīmadbhāgavatamahāpurāṇa, śrīmādhavasevā, part-1, śrīmādhavasevāprakāśana samiti, gopīnāthabāga, vṛṃdāvana, vi. saṃ. 2053, 225

[2] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, śrīmadbhāgavatamahāpurāṇa, śrīmādhavasevā, part-4, śrīmādhavasevāprakāśana samiti, gopīnāthabāga, vṛṃdāvana, vi. saṃ. 2057, 148

[3] https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=John%201%3A14&version=NIV

[4] Śree Bhagavat Rāmānuja, Vedāntadeepa, Vidya Vilas Press, Benares, 1902, 3

[5] Śree Bhagavat Rāmānuja, Vedāntadeepa, Vidya Vilas Press, Benares, 1902, 1

[6] apauruṣeya, īśādinauupaniṣad, gītāpresa, gorakhapura, vi. saṃ. 2010, 281

[7] apauruṣeya, Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, Gītā Press, Gorakhpur, VS 2025, p. 457

[8] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, śrīmadbhāgavatamahāpurāṇa, śrīmādhavasevā, part-1, śrīmādhavasevāprakāśana samiti, gopīnāthabāga, vṛṃdāvana, vi. saṃ. 2053, 45

[9] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, The bhagavadgītā, gītāpresa, gorakhapura, 2007, 177

[10] Shree Vallabhacharya, tattvārthadīpanibandhaḥ, part-1, śrīvallabhavidyāpīṭha – śrīviṭhṭhaleśaprabhucaraṇāśramaṭrasṭa, kolhāpura, mahārāṣṭra, vi. saṃ. 2039, 16-18

[11] https://www.sanskritam.world/upanishads/58

[12] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, śrīmadbhāgavatamahāpurāṇa, śrīmādhavasevā, part-1, śrīmādhavasevāprakāśana samiti, gopīnāthabāga, vṛṃdāvana, vi. saṃ. 2053, 53

[13] bhagavānvyāsaḥ, The bhagavadgītā, gītāpresa, gorakhapura, 2007, 117

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.