Khatara Satra

Introduction

Darrang District, situated on the northern bank of Brahmaputra, is a region known for its harmonious coexistence of diverse religious and ethnic communities. Enveloped by rivers, streams and wetlands, Darrang is home to both tribal and non-tribal populations. The district is home to a vibrant mix of indigenous communities such as the Bodo, Rabha, Garo, and others, reflecting its rich cultural diversity. As a result, the social fabric, cultural expressions, and linguistic practices of the region are deeply influenced by its tribal heritage.

The region now known as Darrang was once called Darrang Desh or the Kingdom of Darrang. According to historical records, the Ahom King Pratap Singha, in 1614 CE, appointed Bali Narayan, thereby formally establishing the Kingdom of Darrang. Prior to this, the area was part of Ancient Kamrup and was referred to as Darrang Desh.

The Darrang kingdom was later incorporated into the larger Koch kingdom. Notably, the entirety of present-day Mangaldoi subdivision and parts of Tezpur subdivision once fell under the dominion of Koch king Naranarayan. While the exact territorial boundaries of ancient Desh Darrang remain unclear, the geographical extent of the Darrang Kingdom during the Koch era is described in the historical chronicle Darrang Rajbanshawali as follows:

North: The foothills of Bhutan and the Gamiri Giri range

East: The Bhairavi or Bharali river

South: The Brahmaputra River, also referred to as Sripahar

West: The Karatoya River

This rich blend of history, geography and culture makes Darrang a distinctive and significant district in Assam. The society of Darrang district is a harmonious blend of diverse communities. It can rightly be described as a melting pot of various ethnic groups and cultures. Darrang’s unique character has crystallised through generations of shared customs and coexistence, forming the vibrant Darrangi culture we know today.

One of the most significant contributors to this cultural landscape has been the region’s Satras (Vaishnavite monasteries), temples, and other religious institutions. These spiritual centres play a vital role in shaping the social and cultural ethos of the district. They host a variety of festivals and religious ceremonies that are deeply rooted in faith and tradition. These events not only reinforce religious devotion but also leave a lasting influence on Darrang’s cultural fabric.

Through such festivals, the Satras aim to impart moral and spiritual values to the masses, guiding them towards a life of righteousness. These institutions also promote cleanliness, disciplined living, ethical conduct, and philosophical awareness, such as the understanding of human existence and divinity. All of this is achieved through participatory celebration and community involvement.

Likewise, the temples and monasteries conduct rituals and festivals intended to eliminate negative forces and invoke positive, welfare-oriented energies in society. These events are inclusive in nature, drawing participation from people across different religions, castes, and communities. Such widespread involvement fosters mutual understanding, emotional connection, and social unity, leading to a healthy exchange of cultural values.

In this way, the Satras and religious institutions of Darrang have profoundly influenced the development and enrichment of Darrangi culture, making them integral to the region’s social harmony and spiritual well-being.

Satras in Darrang District: Introduction & History

(Figure 1: Khatara Satra)

Origin and Evolution of the Term Satra: The use of the term Satra in relation to Vaishnavite institutions and practices marks a relatively new addition to the history of Indian religious traditions. Scholars hold varying opinions regarding the origin and development of Satras, and the term itself has undergone notable evolution over time.

Etymologically, the Assamese word Satra is derived from the Sanskrit term Satra, which traditionally refers to an extended sacrificial session (yajña). References to the word Satra can be traced as far back as the Vedic period, with its usage found in ancient Sanskrit texts such as the Shatapatha Brahmana and the Bhagavata Purana.

In Vedic literature, particularly the Shatapatha Brahmana of the Yajurveda, Satra denotes a long-duration ritual sacrifice. This text, especially in its twelfth chapter, describes twelve distinct Satras, marking some of the earliest known uses of the term in a ritualistic context.

Vedic sacrifices were categorized by duration:

One-day sacrifices were termed ekaha yajnas.

Sacrifices lasting more than one day but fewer than twelve days were known as ahina yajnas.

Those extending beyond twelve days were called Satra yajnas.

Thus, the word Satra originally served as a time-based descriptor for prolonged sacrificial events.

In the Bhagavata Purana as well, Satra is used to describe sacrificial rituals held over extended periods. For instance, in the first skandha (canto) of the Srimad Bhagavatam, the term appears in reference to such prolonged religious ceremonies.

Over time, particularly in Assam, the meaning of Satra evolved from its Vedic and Purāṇic context to denote the socio-religious Vaishnavite institutions established by Srimanta Sankardeva and his disciples. These institutions became centers of religious, cultural, and social life in Assam, far removed from their original association with Vedic sacrificial rites.

Like many other districts of Assam, Darrang too holds a unique place in the spiritual and cultural landscape shaped by the Neo-Vaishnavite movement led by Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardev. To promote and propagate the ideals of this movement, various Satras (monastic institutions) were established in Darrang.

Interestingly, alongside the Assamese term Satra, the word Sakta is also found in use across regions like Darrang, Barpeta, and Kamrup, indicating a seamless confluence between Vaishnavism and other indigenous religious traditions. Numerous Satras were founded in Darrang, and over the centuries, they have continued to serve as vibrant centers for religious festivals, cultural celebrations, and spiritual practice.

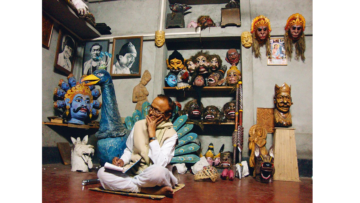

(Figure 2: Maharaja Naranarayan)

While historical records do not extensively highlight Darrang’s role in the early propagation of Neo-Vaishnavism, the district was not untouched by its influence. The Koch kings, beginning with Maharaja Naranarayan and his successors, ruled Darrang for over 160 years. Though primarily adherents of Shaktism, these rulers recognized and respected the teachings of Srimanta Sankardev and supported the spread of Vaishnavism.

As in other parts of Assam, Sankardev’s disciples established Satras in Darrang with the aim of spreading the Vaishnavite faith. The influence of the Vaishnavite reform movement began to be deeply felt in Darrang by the late 16th century. This led to the founding of the Khatara Satra in 1568 AD. It is believed that Gobinda Atoi of Khatara and Krishnadeva of Sipajhar’s Maroi were among the first to successfully establish Vaishnavite Satras in the region, laying the foundation for Darrang’s spiritual legacy within the Neo-Vaishnavite tradition.

Over different periods of time, several Satras were established in Darrang district by various spiritual leaders and their disciples. The influence of the Vaishnavite faith, propagated by Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardev, was also felt in this region, resulting in the foundation of many such monastic institutions.

However, the exact number of Satras in Darrang has been a subject of varying accounts. Different sources provide different figures. For instance, Dr. Maheswar Neog, in his book Pabitra Asom, mentions that there were 28 Satras in Darrang. Yet, in reality, not all of those 28 Satras are presently in existence or functioning.

Another authoritative source, the book Darrangar Itihas (The History of Darrang), states that there were 24 Satras in the district. This variation in numbers reflects both the passage of time and the differing methodologies of documentation across scholars and historical records.

The prominent Satras (Vaishnavite monasteries) of Darrang district are:

Khatara Satra, Debananda Satra, Mabo Satra, Outola Satra, Pora Satra, Patharughat Satra, Deomornai Satra, Chaturbhuj Satra, Chintamaniya Satra, Kapili Satra, Kuruwa Dihing Satra, Narayan Satra, Patidarrang Satra, Palangia Satra, Barangajuli Satra, VishwaSatra, Bainara Satra, Baragi Satra, Bamundi Satra, Bhavadeva Satra, Bhagawati Satra, Donaji Satra, Batnaboli Satra, Randhani Satra, Sholguri Satra, Shagunbahi Satra, Haripur Satra, Padumpukhuri Satra, and others.

These Satras are significant centers of Assamese Vaishnavite culture, spiritual learning, and cultural heritage.

Khatara Satra and the Festivals Celebrated Here:

(Figure 3: Main Deity of Khatara Satra)

As per historical accounts, the Khatara Satra belongs to the Nika Sanghati of the Vaishnavite order. Located in the village of Khatara under Dipila Mouza, west of Mangaldai town in Darrang district, this Satra holds great religious and historical significance. It was established in 1568 AD by Lechakonia Govinda Atoi, a devoted disciple of Mahapurush Madhavdev. Among the twelve principal disciples of Madhavdev, Govinda Atoi was notable for his courage and strength.

Born in a place called Lechakona near Rangiya in present-day Kamrup district, Govinda Atoi accepted the Vaishnavite faith under the guidance of Madhavdev and began propagating the Ekasarana Dharma. Recognizing his bravery, Madhavdev sent him to Darrang—a region with a strong Shakta (Tantric) influence at the time—to spread Vaishnavism.

Upon reaching a dense forested area inhabited by unruly and faithless people with violent tendencies, known as “Khots”, Atoi moored his boat and began his mission in the village now known as Khatara. These Khots opposed and obstructed his attempts to preach the Vaishnavite teachings. Despite facing hostility, Govinda Atoi did not waver. He continued urging the Khots to surrender at the feet of the Guru and accept the Vaishnavite path, but they persistently ignored his appeals. Disheartened but not defeated, Atoi returned to Madhavdev and narrated the situation in detail.

Moved by his disciple’s perseverance, Madhavdev entrusted Atoi with four sacred idols—Rama, Lakshmana, Sita, and Hanuman—which he had brought from Ayodhya for the Ramleela performances. He advised Atoi to begin the spiritual transformation of the Khots through the worship of these idols, using the Saguna (with form) path initially, so that they could eventually grasp the concept of Nirguna (formless) devotion.

After the installation of the idols and the establishment of the worship practices, four of the fiercest Khots were eventually moved by the spiritual teachings and surrendered themselves to the Ekasarana Dharma under the guidance of Govinda Atoi. This marked the beginning of the transformation of the village. The once wild and lawless place filled with darkness and hostility was gradually illuminated by the light of devotion and discipline, as Atoi founded the Satra there.

Because Govinda Atoi conquered the evil nature of the Khots and turned them toward the path of righteousness, the place came to be known as “Khot-Hara”—meaning “the one who removed the Khots”—which later evolved into “Khatara.”

The Khatara Satra thus stands as a testament to the transformative power of devotion, perseverance, and the teachings of Mahapurush Madhavdev. Over the centuries, it has continued to be a center for religious and cultural festivals rooted in the Vaishnavite tradition.

Legend holds that Govinda Atoi chose this very spot to kindle the flame of Ekasarana Dharma after witnessing a miraculous reversal of nature: a frog swallowing a snake. Interpreting this extraordinary sight as a divine omen, he recognized the location’s spiritual potency and decided it was uniquely suited for his mission of religious propagation.

From its very founding, Khatara Satra enjoyed the support of local rulers. A royal charter (Borkakot) issued by King Dharmanarayan of Darrang—still carefully preserved within the Satra—records its formal establishment in 1568 AD under the reign of Maharaj Naranarayan. This royal endorsement not only conferred legitimacy but also ensured the Satra’s early growth and protection.

Local tradition further credits a prominent figure, Krishnai Deka, with playing a decisive role in the Satra’s creation. His influence and resources helped secure community backing and provided the practical means by which Govinda Atoi could construct the first prayer hall and begin the work that would transform Khatara into a lasting center of devotion.

Since its inception, the Khatara Satra has remained a spiritual fulcrum, drawing hundreds of devotees with its deep-rooted aura of devotion. Even today, one can witness the unwavering faith of devotees who continue to remain spiritually connected to the Satra, just as they did in the past when they sought the blessings of ‘Baghunath’. Without a doubt, the Satra will continue to be revered as a sacred pilgrimage site for generations to come.

Many refer to the Khatara Satra as the ‘Ghatana Gosai Ghar’ or the ‘Raghunath Mandir’. Interestingly, in Darrang district, where the concept of a ‘Satra’ might not be as commonly understood by the general public, people often refer to it simply as a ‘Mandir’ (temple) or a ‘Gosai Ghar’ (the abode of the Lord).

During the early days of its establishment, the founder Atoi faced considerable resistance from the local Khat community. However, over time, that resistance faded and he eventually received widespread support. A popular folk song vividly portrays the awe and reverence people feel:

“Khatara Gosai Ghar dekhote bhoyonkor, Hari mor oi soykuri naharar khutaha!”

(Meaning: The sight of Khatara Gosai Ghar is awe-inspiring — O Lord Hari, it rests on sixty strong pillars!)

Thanks to the collective support of the local community, Atoi was finally able to build this revered Namghar, which today stands not just as a place of worship, but as a symbol of resilience, devotion, and unity.

The historic Khatara Satra in Darrang district is unique among Assam’s many Satras, as it does not have a traditional Satradhikar (spiritual head). Unlike other Satras across the state that are typically governed by a single religious authority, Khatara Satra operates through a democratic system led by elected representatives.

According to the records of the Satra’s head priest, revered spiritual figure Gobinda Atoi once initiated and mentored thirty-three devout individuals, ordaining them as religious guides to spread the principles of neo-Vaishnavism. In his mission to promote the faith, Gobinda Atoi also gave due importance to traditional local customs and practices, ensuring that spiritual teachings resonated with the cultural sentiments of the community.

This inclusive approach helped Khatara Satra become a spiritual and cultural institution that people from all walks of life could relate to and take pride in. Since the time of Gobinda Atoi, a man of deep cultural wisdom, the Satra has earned a reputation as a vibrant center of both Sattriya and folk traditions, continuing to uphold its legacy as a hub of spiritual and cultural excellence.

Since its inception, the Khatara Satra has grown into a vibrant centre of cultural expression. From its early days, the Satra has hosted a wide array of religious and cultural performances such as naam-prasanga, borgeet, thiyanam, khol-badan, charchapari naam, nagara naam, Ankiya Bhaona, and Boka Bhaona. Among its distinctive contributions, the “Khuliya Bhaona” stands out as a symbol of Darrangi cultural heritage.

Located in Darrang district, the Khatara Satra serves as a spiritual and cultural hub for people from various ethnic and tribal communities. Notably, the Satra does not have a traditional Satradhikar (head monk). Instead, its day-to-day affairs and religious activities are managed by an executive committee, elected by the local devotees. Specific individuals are entrusted with responsibilities such as lighting the sacred lamps and maintaining other essential rituals of the Satra.

One of the unique features of Khatara Satra, often referred to as “Gosai Ghar,” is the installation of idols of Lord Ram, Lakshman, Sita, and Hanuman inside the sanctum sanctorum (Manikut). Traditionally, Vaishnavite Satras do not enshrine idols; instead, they honour the sacred scripture Bhagavat and the seat of the Guru. However, the presence of idols in Khatara Satra sets it apart from other Satras. While Vaishnav followers continue to offer prayers and light lamps before the Bhagavat placed outside the sanctum, devotees from Shakta traditions worship the deities installed within the sanctum.

Since ancient times, Khatara Satra has celebrated numerous religious festivals and rituals with great devotion and splendour. These include:

- Pacheti (Pachati) Festival

- Doul or Phakuwa Festival

- Deul Utsav on 15th Bohag

- Borgopini Sabha on the full moon day of Bohag

- Borsobha (Annual Congregation) in the first week of Jeth

- Tirobhav Tithi (Death Anniversary) of the founder Govinda Ata on Krishna Chaturdashi of Shravana month

- Suberi, Nandotsav

- Birth and death anniversaries of Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardev and Mahapurush Madhavdev

- Janmashtami

- Bihu celebration

Through these events, Khatara Satra continues to uphold and propagate the spiritual and cultural traditions of Assam.

Festival Traditions of Khatara Satra

The Sattriya festivals of Assam can broadly be classified into two categories: fixed-calendar festivals and non-fixed calendar festivals. In this context, noted scholar and Satradhikar Dr. Pitambar Dev Goswami has observed that Satras conduct both these types of festivals. A detailed explanation of this classification has been provided earlier.

At Khatara Satra, located in Darrang district and known for its deep-rooted traditions and emphasis on harmony, only the fixed-calendar festivals are predominantly observed. Unlike some other Satras, Khatara Satra does not have a significant tradition of hosting non-fixed calendar festivals. The celebrations here are primarily based on local customs and age-old Sattriya values. The major festivals observed at Khatara Satra can be classified as follows:

1. Date-specific Festivals (Tithi-based):

Annual commemoration of revered Gurus (Gurus’ Tithi)

Bargopini Sabha

Nandotsav

2. Star-specific Festivals (Nakshatra-based):

Janmashtami

Phakuwa (Holi)

Panchati

3. Solstice/Equinox-based Festivals (Sankranti-based):

All three Bihu festivals (Rongali, Bhogali, and Kongali)

4. Month-specific Festivals:

Bohag-mahiya Deul (temple rituals in the month of Bohag)

Jeth-mahiya Bar Sabha (a major community gathering in Jeth)

Kati-mahiya Bhagavat Path (recitation of the Bhagavat in Kati)

Additionally, the ritual of “Gondha (গোন্ধ)” is performed on the eve of major festivals at Khatara Satra is also considered an important ceremonial tradition and can be regarded as a festival in itself.

These festivals, steeped in devotion and cultural heritage, reflect the unique spiritual identity and community life nurtured by Khatara Satra over the centuries.

Pacheti Utsav: A Blend of Devotion and Tradition

(Figure 4: Pacheti Festival)

Pacheti Utsav, locally known as ‘Pacheti’ in the Darrang dialect, is a unique festival rooted in devotion and folklore rather than being a conventional seasonal observance. Though it was originally celebrated on the fifth day after Janmashtami—the birth anniversary of Lord Krishna—over time, the festival came to be observed during the transitional phase between the Assamese months of Bhado and Ahin, specifically on the first day of Ahin.

Traditionally, the festival begins on the last day of Bhado, aligning with the seasonal transition (domahi), and continues into Ahin. In recent times, depending on the local context and community involvement, the celebration often extends for up to three days. Despite its evolving schedule, the central theme of Pacheti remains the celebration of Lord Krishna’s birth and early life, deeply rooted in Vaishnavite devotion.

One of the folk beliefs associated with this festival is linked to the social custom of moving a newborn from the mother’s quarters to another place on the fifth day after birth. Drawing inspiration from this tradition, Pacheti Utsav commemorates the fifth day after Lord Krishna’s birth, symbolically marking his movement from the place of birth, often interpreted through rituals in Assam’s Satras (Vaishnavite monasteries).

The Khatara Satra, like many others, has preserved and continued this tradition through age-old customs and spiritual practices. However, considering that Janmashtami usually falls during the heavy monsoon and peak rice cultivation period, the festival was gradually shifted to a more practical time—post-harvest, in the relatively dry and calm days of Ahin.

In many regions, Pacheti is celebrated much later, sometimes during the Kati or Aghon Sankranti, with some oral traditions suggesting that fear of King Kansa led to the delayed public celebration of Krishna’s early days. Regardless of when it is held, every year the Pacheti Utsav is celebrated with joy, devotion, and community participation, anchoring the spiritual significance of Krishna’s life in local cultural practices.

It is often argued that the origin of the Pachoti festival dates back to the days of Gobinda Atoi. If this tradition has been in place since the establishment of the Satra (Vaishnavite monastery), then it is beyond doubt that the Pachoti festival is around 450 years old. The central ritual of the Pachoti festival at Khatara Satra is the Dadhimanthan (or Dadhimathan)—a ritual churning of curd. Accordingly, the Satra continues to uphold the tradition of Dadhimathan dance and Dadhimathan drama or performance.

At Khatara Satra, the day before Sankranti (the transition of the sun from one zodiac sign to another), the priests of the Satra observe ‘Adhibas’, a customary rite. This day is referred to as ‘Pachotir Gondh’ (the fragrance of Pachoti). On this day, earthen lamps and incense sticks are lit in the sanctum (Namghar), and traditional offerings are made. A Bhagavata scripture is placed beneath a bamboo frame in the center of the hall. A bamboo and banana stem structure is constructed to carry out the Dadhimathan ritual. In the evening, the Namghar resonates with devotional songs and kirtan marking the Gondh day.

The construction of the ‘Mothani Shal’ (churning structure) reflects the skill of local artisans. The decorated structure usually has six wooden poles, each about three hands tall, fixed at equal distances. These poles are joined by a crossbeam or a perforated batam (wooden plank). Five bamboo sticks, each six hands long, are inserted with two opposite holes at their tops. Two bent wooden bows are inserted through these holes in a crisscross manner. At the ends of the bows and bamboo sticks, jute ropes are tied to create the churning frame. A bamboo funnel is attached at the base, and wooden wheels are fixed under each bow. The upright bamboo poles are tightly bound with rope, so that pulling either side rotates the central bamboo. This entire setup is known as the five Dadhimathan Shal. To the east of the central churning hall, two banana stems are placed.

In the evening, after the Gondh songs, Nam-Prasanga (chanting and kirtan) begins in the Namghar. After the chanting, the Bhagavata scripture is ceremoniously brought to the churning site by a priest. The scripture is placed on the churning platform with accompaniment of singing and drumming.

Following tradition, holy water is collected by a designated priest or a representative dressed as Subhadra (a female figure from Krishna’s legend). During the ritual, the person wears women’s attire and carries a brass plate with five mustard oil lamps, a pair of betel leaves and areca nuts, and a water pot in the other hand. The entire group, including singers and musicians, proceeds to the pond. The betel leaves are offered into the water, and the pot is filled. The Subhadra impersonator then returns to the Namghar, circling it three times before entering the Mothani Shal, where the water is poured into the pot designated as the curd vessel.

Subhadra leads the procession, followed by children dressed as Gopinis (female devotees), who circle the Mothani Shal and begin the Dadhimanthan ritual. During the churning, the Sutradhar (narrator) recites verses, and the performers dance around the churning structure, repeating those verses. The following are some of the traditional songs (Dihas) sung during the ritual procession with the filled pot around the Namghar:

1. ঘিউৰ বাতি লৈ কৃষ্ণকে মাতোগৈ

ঘিউৰ বাতি লৈ কৃষ্ণকে মাতোগৈ।।

(With a lamp of ghee, call out to Krishna,

With a lamp of ghee, call out to Krishna.)

2. খটোৱা এ দধি মথনে যায়।

বস্ত্র অলংকাৰে মন দিছে কায় এ।।

(Khatuwa (a devotee) goes for the churning of curd,

Dressed in fine clothes and ornaments, the body is adorned with devotion.)

3. যশোৱা এ দধি মন্থন কোলে

আঞ্চলে ধৰিয়া গোপালে বোলে।।

(Yashoda churns the curd, holding Gopal close at her side,

She speaks gently to him as she churns the curd.)

Verses sung in the Mothani Shal during the Dadhimanthan:

মথনি এ ধৰউ টানিয়া

মথনি এ ধৰউ টানিয়া

বাৰিষাৰ গোপ-গোপী ভুৱন তুলিয়া।

যশোৱা এ মাতিছে দধি মথিবাকে

যশোৱা এ মাতিছে দধি মথিবাকে

উতলি পৰয় দধি নৰেই ৰাখিবাকে।

যশোৱা এ দধি মথে মথেনি গিৰে গিৰাই

বাৰিষা কালতে মেঘে বৰষে শুনিও যাদৱ ৰায়।

(Hold the churner and pull it tight,

Hold the churner and pull it tight—

The Gopas and Gopis of Barisha (a divine realm) lift the world in joy.”

“Yashoda calls out—‘Come churn the curd!’

Yashoda calls out—‘Come churn the curd!’

The curd overflows, how can I preserve it?”

“Yashoda churns the curd, spinning the churner round and round—

Even as clouds pour during the monsoon, listen, O Yadav Rai.)

During the performance of the Dadhi Mathan (churning of curd) song and dance, as the song progresses, Yashoda is seen completing the churning process in harmony with the narrative. In a graceful conclusion, she lifts the child Krishna into her lap, symbolically ending the Dadhi Mathan sequence.

As the act of churning concludes, the performance transitions into “Thiyanam” beneath the Rava (the sacred canopy or platform). In this concluding segment, devotional verses are sung in praise of Lord Krishna — including passages from the Kirtan, Dashama, and Namghosha — glorifying his divine play and virtues.

On the day following Paachoti (the fifth day), the traditional performance of Dadhimanthan Bhaona (a theatrical reenactment of the churning of curd) is staged in the afternoon. Even on the day of Domahi—that is, the fifth day—the Deuri (priest) lights ceremonial lamps (chakibonti) in the Naamghar (community prayer hall) and offers tributes with devotion. The Bhagavat scripture, which was installed the previous day, is ceremonially brought out from the Naamghar and reinstalled under the sacred Robha tree in the open courtyard. Alongside the Bhagavat, an idol made of Kusha grass, symbolizing Lord Krishna, is also brought out and placed with reverence.

On Paachoti, apart from witnessing the Dadhimanthan enactment, devotees gather in large numbers to offer prayers and seek blessings from the idols of Ram, Lakshman, Sita, Hanuman, and the twins Lav and Kush. Pilgrims and devotees from not only Darrang district but also neighboring districts arrive in large numbers. A significant portion of the visitors consists of women and young girls, especially from indigenous tribal communities, who come dressed vibrantly, adding color and liveliness to the fair.

Regardless of caste or creed, people converge at the Khatora Satra on Paachoti, transforming the entire area into a grand festive celebration. One notable sight on this day is the massive sale of coconut sweets (narikolor puli), which are seen in abundance. Homes across the region fill with guests and relatives, creating an atmosphere of warmth and hospitality.

The day after Paachoti is celebrated as Bahi Paachoti. Since most people are occupied entertaining guests on the main day, they are unable to actively participate in the festivities. Therefore, Bahi Paachoti offers a special opportunity for local residents, particularly women, to take part in the celebration. On this day, the devotees of the Satra perform the traditional Boka Bhaona, a unique and humorous form of folk drama.

Solstice-Centric Celebrations

Bihu as a National Festival

(Figure 5: Credit: Istock – Bihu Dance of Assam)

Just as various folk festivals are celebrated in Assamese society following age-old traditions, the Satra institutions too observe these festivals in their own distinct way. Among them, Bihu—a central festival in Assamese life—found its way into the Satra tradition during the Ahom era, following the rise of Srimanta Sankardev’s Vaishnavite movement. However, the way Bihu is celebrated within the Satra system differs significantly from how it is observed in general folklife.

In Satras, folk festivals like Bihu are imbued with spiritual significance. These celebrations are preserved and practiced not merely as cultural rituals, but as mediums for spiritual education and devotion. Thus, within the Satra framework, Bihu is celebrated with an emphasis on inner purity, discipline, and religious observance.

Like many other Satras, Khatora Satra also regards Bihu as a solstice-centric festival. All three Bihu festivals—Rongali, Kati, and Magh Bihu—are observed here in accordance with Sattriya ideals of sanctity, traditional rites, and spiritual values.

Celebration of Bihu at Khatara Satra

Bohag Bihu

(Figure 6: Credit: Istock – Bohag Bihu Preparation)

At Khatara Satra, Bohag Bihu is observed on the day of Bohag Sankranti. The celebrations begin early in the morning with the hoisting of the Dharma Dhwaja (religious flag) at a designated place in front of the Satra. As the flag is raised, the Gayan-Bayan (traditional devotional musicians) perform the Gurughata, and the devotees chant the Bastu Prakash Ghosha. After the flag hoisting, participants exchange respectful greetings, known as Sewa.

On this day, the Satra’s priests offer new ceremonial garments (Bihuwan) to the sacred idols of Lord Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Hanuman, and Lava-Kusha, which are enshrined in the Monikut and Guru Asana of the Kirtanghar. A collective devotional gathering (Samuhiya Prasanga) is then held. Unlike regular devotional sessions, this Bihu gathering sees participation not just from the Satra community but also from visiting pilgrims and devotees.

During the Bihu Prasanga, traditional chants like Naam Chandha and Saran Chandha are sung, followed by three special Kirtans, a customary practice for this occasion. At the end of the session, everyone receives Nirmali—first offered by the chief priest to the congregation. Following this, the secretary or president of the Satra’s management committee formally extends Bihu greetings to all attendees. The priests invoke blessings and chant Hari Dhwani for the well-being of all in the new year. With the distribution of Prasad, the first day’s celebrations conclude.

On the second day of Bohag Bihu, the management committee members gather. The Satra’s secretary offers Bihuwan and greetings to the members, priests, storekeepers, and the Gayan-Bayan ensemble.

On the sixth day of Bohag, an open-air cultural event is organized in the Pachatikhol area of the Satra, now a well-established tradition. The atmosphere on this day turns festive, with the hosting of various competitions including sports, literature, singing, and elocution. Additionally, programs like agricultural discussions and animal healthcare camps are occasionally arranged. Through these events, not only is national culture preserved, but bonds of unity and brotherhood are also strengthened among the people.

Kati Bihu

Kati Bihu is observed at the Satra on the Sankranti of the Assamese months of Ahin and Kati. In the evening, the traditional Bargosa (sacred fire) is lit at the Satra. While some places and Satras light Aakash Bonti (sky lamps), this is not practiced at Khatara Satra. In certain Satras, Tulsi Puja (holy basil worship) is also performed, as Kati is believed to be a month dear to the divine. In many villages, continuous Bhagavat recitation during the nights of this month is a longstanding tradition.

(Figure 7: Credit : Istock – Kati Bihu)

At Khatara Satra, more Ghosha and Kirtan verses are sung during Kati Bihu than on regular days. The devotional session is followed by Thiyanam (standing devotional songs). The Khol-Badan (drum accompaniment) of the Gayan-Bayan is an indispensable part of the proceedings. Starting from the day after Kati Bihu, a continuous Akhanda Bhagavat Path Chakra (unbroken scripture recital) is held in the Kirtanghar. The spiritual vibrancy of these sessions provides solace and profound inner peace to the troubled minds of devotees, inspiring a deep sense of divine joy.

These devotional recitations attract not only local devotees but also men and women from distant areas, adding solemnity and spiritual significance to the occasion.

Magh Bihu

Magh Bihu is celebrated at Khatara Satra on the Sankranti of the Assamese months of Puh and Magh. Devotees from the nearby areas light the traditional Meji (bonfire) in their villages early in the morning and arrive at the Satra carrying offerings. Once assembled, they proceed to the front of the Satra, chanting Hari Dhwani (devotional slogans). This chant is performed thrice—first in front of the Satra, then again outside the Monikut, and finally in front of the Guru Griha. Led by the Bhorali (storekeeper), the priests recite Hari Dhwani five times for the well-being of all.

Only after these chants does the collective devotional session begin. Notably, according to Satra tradition, the Samuhiya Prasanga on Magh Bihu is held in an open space on the southern side of the Kirtanghar. This tradition is believed to have two main reasons:

- The earth’s motion begins to tilt southward (Dakshinayan) from this time of the year, symbolizing the spiritual orientation of the gathering.

- Owing to the extreme winter cold and the previously poor condition of the Kirtanghar, the open southern area, warmed by sunlight, was chosen for the devotional gathering.

On this day, every household associated with the Satra contributes their annual offerings or Gurukar (religious donations). After the collective Sewa, Prasad is distributed to all. Traditionally, this day also marks the conclusion of the year-long tenure of the Satra’s staff and office bearers, and a new team is appointed. However, in present times, such appointments are often scheduled for a more convenient date, as determined by the Satra’s management.

Observance of Bihu and Tithi-Based Festivals at Khatara Satra

At Khatara Satra, the three Bihus—Bohag Bihu, Kati Bihu, and Magh Bihu—are celebrated as seasonal festivals rooted in the transitional points of the solar calendar (Sankranti) with deep adherence to Sattriya traditions and rituals.

Tithi-Based Celebrations at Khatara Satra

In addition to Sankranti-centered festivals, Tithi-based observances hold a special place in the spiritual life of Khatara Satra. These include commemorations of the birth and death anniversaries of Satra founder Sri Sri Gobinda Ata, and the death anniversaries (Tirobhav Tithi) of Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardeva and Mahapurush Madhavdeva.

a) Tirobhav Tithi of Sri Sri Gobinda Ata: The death anniversary (Tirobhav Tithi) of Sri Sri Gobinda Ata, the revered founder of Khatara Satra, is observed with great devotion and reverence on the Shukla Chaturdashi of the Assamese month of Saawan (Shaon). Devotees from near and far gather at the Satra on this auspicious day to participate in a collective devotional assembly (Naam-Prasanga), initiated by the Satra’s priests.

As part of the ritual, an additional Kirtan is sung, which distinguishes this observance from regular devotional sessions. After the Naam-Prasanga, a recitation of Gobinda Charit, composed by Bhabananda Dwij, takes place in front of the Guru Griha—the residence of Gobinda Ata situated on the southern side of the Satra. This is followed by a traditional Khol-Prasanga performed by the Gayan-Bayan.

In the evening, devotees perform Thiyanam (devotional singing while standing). Notably, this Tirobhav Tithi is also celebrated with grandeur at Gobinda Ata’s Smriti Namghar in Kaikiyapara, where devotees from the entire region gather in large numbers to offer their respects.

b) Tirobhav Tithi of Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardeva: The death anniversary of Mahapurush Srimanta Sankardeva, the great Vaishnavite saint and social reformer, is observed on the Shukla Dwitiya Tithi of the Assamese month of Bhadra (Bhado). Despite it being a season of heavy rain and intense agricultural activity, devotees and local residents make a sincere effort to be present at the Satra from the early morning.

A formal Naam-Prasanga is held where the congregation pays heartfelt tribute to the Guru. Alongside this, recitations from the Guru Charit are conducted. The Gayan-Bayan ensemble performs the traditional Khol-Prasanga. Depending on the setting, Ankiya Naat—a one-act play authored by Sankardeva—is also staged as part of the observance.

c) Tirobhav Tithi of Mahapurush Madhavdeva: The Tirobhav Tithi of Mahapurush Madhavdeva is commemorated on the Krishna Panchami of Bhadra month. This day holds profound significance for Khatara Satra, as it was Madhavdeva who provided continuous guidance and spiritual counsel to his disciple, Sri Sri Gobinda Ata, to overcome the challenges faced during the establishment of the Satra.

Hence, the Tirobhav Tithi of Madhavdeva is celebrated with immense devotion and festivity by the Satra’s devotees, followers of the Vaishnavite Satras, and local communities. It serves not only as a moment of remembrance but also as a reaffirmation of spiritual lineage and unity.

Nandotsav at Khatara Satra

The day following Janmashtami, Khatara Satra celebrates Nandotsav—a joyful festival symbolizing the immense delight that once swept through King Nanda’s household upon the birth of Lord Krishna. At Khatara Satra, this celebration has evolved into a distinct tradition, marked by its unique feature: the “Boka Bhaona”.

The “Boka Bhaona” – A Blend of Devotion and Joy

The Boka Bhaona is a vibrant theatrical ritual that merges spiritual devotion with playful celebration. One of its most remarkable elements is the symbolic creation of “Boka” (holy mud), which is central to the event. Sacred soil is collected from a consecrated spot and placed in the courtyard of the Kirtan Ghar (Prayer Hall). This soil is then sprinkled with holy water brought from the Satra’s main pond (Bor Pukhuri). A mixture of ghee, honey, and other traditional ingredients is added to form the sacred mud.

Devotees, Vaishnavites, and local participants gather around and, amidst collective Naam-Kirtan (devotional singing), immerse themselves in the mud, smearing it playfully on one another in a joyful and symbolic act of unity. This act of rolling in the Boka and applying it to others is regarded as a meritorious and purifying ritual, blending festivity with faith.

Folk Beliefs and Ritual Significance

According to popular belief, merely participating in or witnessing the Boka Bhaona during Nandotsav is said to bestow spiritual merit. It is also widely believed that a drop of Boka water can cure diseases and ward off evil. Hence, the tradition of touching or collecting Boka water is deeply rooted in local faith.

After hours of exuberant celebration and symbolic play, devotees, covered in sacred mud, chant devotional hymns as they circumambulate the Kirtan Ghar. They then proceed to bathe in the Bor Pukhuri, thereby completing the ritual purification.

Though bathing in the Satra’s sacred pond is usually prohibited, an exception is made on this holy occasion. It is believed that because Boka Bhaona is a sanctified ritual, the act of bathing in the pond on this day does not violate any religious norms. On the contrary, devotees believe that the Boka used during the Bhaona further sanctifies the pond’s waters.

Such is the spiritual power attributed to this event that even brides and grooms from distant regions are brought to the Bor Pukhuri, where, accompanied by Naam-Kirtan, they collect water for their wedding rituals, believing it will bless their union.

Bor Gopinir Sabha: A Spiritual Congregation of Devotion and Harmony

Held every year on the full moon day of the Assamese month of Bohag, the Bor Gopinir Sabha is a traditional and ceremonious gathering of women devotees from far and near. This time-honored organizational event marks its conclusion with grandeur in the sacred courtyard located on the southern side of the Kirtan Ghar, known as the Guru Griha.

Here, the women—reverently referred to as Gopinis—engage in devotional singing (naam-kirtan), culminating the event in a deeply spiritual atmosphere. Locally, this concluding session is popularly known as Bor Gopinir Naam. It is believed that the event derives its name from the prominent and active role played by the women in the devotional proceedings, leading to its designation as Bor Gopinir Sabha or Bor Gopinir Naam.

During the Sabha, the women not only sing ghosha and kirtan verses but also melodious dihanaam compositions. Beyond the musical devotion, the gathering becomes a sacred space for fostering mutual respect, understanding, and spiritual camaraderie among the participants. The collective chanting inspires a divine atmosphere in their households and encourages broader participation in the glorification of the divine through naam-kirtan, infusing the community with spiritual energy and unity.

Star-Centric Festivals

Among the star-centric festivals celebrated at Khatara Satra, the following are significant:

(a) Pachati or Pacheti,

(b) Janmashtami, and

(c) Phakuwa or Doul Utsav.

While Pacheti has been discussed earlier, let us now focus on Janmashtami — celebrated on the Krishna Ashtami tithi of the Bhadra month, marking the divine birth of Lord Shri Krishna. At Khatara Satra too, this auspicious day is observed with deep devotion as Krishna Ashtami.

According to Hindu belief, whenever adharma (unrighteousness) overwhelms the world and the lives of the righteous are plagued by the wicked, Lord Vishnu incarnates to restore dharma, destroy evil, and protect the virtuous. It was with this divine intent that Lord Krishna was born in the prison of King Kansa, as the eighth son of Devaki and Vasudeva. As per astrological texts, Krishna was born during the Jayanti Yoga in the solar month of Bhadra. Religious tradition holds that observing this particular tithi brings immense spiritual merit. Based on this deeply rooted belief, Janmashtami is celebrated with great reverence across India.

Just like in other Satras of Assam, Khatara Satra celebrates Janmashtami with its own distinctive rituals and spiritual customs. The festival is entirely faith-driven, and certain dietary observances are also followed during the occasion. On the night of Janmashtami, the Satra becomes a hub of devotional fervor — with continuous naam-kirtan (chanting of Lord Krishna’s name) and the resounding beats of the Borna Nagara (a large ceremonial drum). In addition to devotional singing, the Satra also organizes bhaona (traditional Vaishnavite theatre) showcasing dramatizations of Krishna’s divine birth and childhood leelas (miraculous deeds).

Phakuwa or Doul Utsav: A Prominent Festival of Khatara Satra

(Figure 8: Credit: Istock – Colors of Phakuwa Jatra)

Phakuwa, also known as Doul Utsav, is one of the most significant traditional festivals observed at Khatara Satra. It is a devotional and ceremonial event celebrated during the full moon of the Phagun or Chaitra month, marking the vibrant festival of colors.

The festivities commence with the ritual of Adhibas, performed with spiritual sanctity on the eve of Phakuwa. On the main day, in the presence of the Satra’s Deori (priest) and the gathered devotees, naam-kirtan (devotional chanting) is performed. The sacred scripture Bhagavata, representing the divine presence, is ceremoniously brought from its designated place and installed at a special location called the Phakuwa Khola, accompanied by rituals and devotion.

As the Satra does not house a physical idol of Lord Krishna (locally referred to as Kaliya Gosai), the Bhagavata Grantha is revered as a symbolic representation of the deity. In earlier times, idols of Lav and Kush were used during Phakuwa, brought from the Monikut; however, this practice has been discontinued due to its lack of alignment with the philosophical foundation of the festival.

Being a festival of colors, it is customary during Phakuwa to throw colored powders (abir or phakuguri), an act considered spiritually significant. There is a folk belief that applying abir to the body helps cure various ailments. The priests, carrying vessels filled with abir, joyfully sprinkle it among the crowd, creating a mesmerizing scene.

Following the conclusion of religious rituals in the evening, the symbolic Bhagavata—representing Lord Krishna—is respectfully returned and reinstalled in the Kirtanghar (prayer hall).

The celebrations continue for two or three days beyond the main event, with the traditional Suweri procession visiting the surrounding areas of the Satra. If any individual or public Namghar formally invites the Satra for a visit, the Deori and accompanying devotees carry the Suweri procession with naam-kirtan, offering Sarai (ritualistic offerings) at the host’s premises. The ritual includes recitation of devotional songs and symbolic performances by the Thiyanam and Gayan-Bayan groups of the Satra. The host, in turn, respectfully welcomes and receives blessings from the devotees.

On the final day, the Suweri procession is taken to the southern side of the Satra, locally known as Dakshinhati. This concluding event is particularly dramatic and symbolic, marked by the ritual known as Garbhanga (breaking of the barricade). Here, the southern residents construct a symbolic barrier or Garh using bamboo, representing the opposition of Ghunu Sabarir (a mythical character) to Lakshmi Griha (a metaphor for the Satra’s Kirtanghar).

As the Suweri procession approaches the barricade, the southern group attempts to stop them. A symbolic clash ensues, resulting in the breaking of the bamboo barricade, after which the devotees attempt to enter the Kirtanghar representing Lakshmi’s abode. While entering, they perform naam-kirtan (specifically the Ghunu Sa Kirtan) and circumambulate the Satra three times before entering.

Before the sacred scripture (Bhagavata) can be reinstalled, the group representing Lakshmi poses various symbolic questions. Only after these questions are answered and Lakshmi’s conditions are fulfilled is the Bhagavata reinstated in its rightful place. The entire celebration concludes with the devotees chanting “Hari Dhwani” (praises of the Lord), bringing the festival to a spiritually uplifting close.

Month-Centric Festivals at Khatara Satra

In Darrang district, certain traditional festivals are celebrated in alignment with specific months and seasons. Among them, the Deul Utsav at Khatara Satra is centered around Lord Vishnu. The festival bears resemblance to the Bhatheli festival of Kamrup and is notably observed on the 15th day of the Bohag month, as is customary in many parts of Darrang.

The historical rulers of Darrang played a crucial role in expanding and popularizing this festival, organizing the Deul Utsav with large public gatherings. At Khatara Satra, a mugur (ceremonial pole) is ritually installed on the sacred Deul Vitha (altar) located to the north of the Pachati Khalab section. The Deuris (temple priests), accompanied by the gayan-bayan (traditional music ensemble) and bearing traditional items like the dhal (shield) and chatra (umbrella), proceed from the Kirtanghar in a ceremonial manner. With devotional fervor, they place the symbolic idol of Bhagawan on the southern side of the altar.

The event includes vibrant theonam (standing devotional songs) performed by the Satra’s devotees. A hallmark of this festival is the open-air bhaona (traditional drama), typically enacting stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. As night falls, the festival concludes, and the Deuris respectfully bring back the Bhagavat scriptures from the altar to their rightful place in the Satra.

This Deul Utsav is a prominent socio-religious celebration of Khatara Satra, contributing significantly to preserving and promoting the Satra’s spiritual and cultural heritage.

a) Deul in Bohag Month: Throughout the month of Bohag, Deul Utsav is celebrated across several parts of Darrang and Kamrup. At Khatara Satra too, rituals during mid-Bohag closely resemble these regional customs.

b) Borsabah: The Borsabah festival is observed in the first week of the Jeth month. Among the various important dates observed by the Satra, Borsabah holds a unique significance. Preparations begin the evening before, traditionally referred to as gondh in the local dialect. The night includes performances of biya oja-pali (a traditional lyrical narrative form). Prior to the performance, theonam is sung under the guidance of the Deuris with active public participation. The following day, after the devotional songs, male and female devotees offer naibedya (sacred food) and express their gratitude by invoking the blessings of Lord Raghunath. A week after Borsabah, devotees once again gather to perform theonam, which may also include participation from outside the Satra community.

c) Bhagavat Recitation in Kati Month: The Satra observes Kati Bihu on the day of Sankranti between the months of Ahin and Kati. On this occasion, the traditional Bargacha (sacred tree) is lit in the evening. Unlike some other regions where sky lanterns are lit throughout the month, this is not a tradition at Khatara Satra. While Tulsi worship is also practiced in some Satras, Kati is widely regarded as a sacred month dedicated to the Lord. Thus, in most Satras and village namghars across Assam, continuous Bhagavat recitations and lighting of lamps are performed. At Khatara Satra, these recitations begin from the day of Kati Bihu, drawing in devotees—both men and women—from far and wide.

In this manner, Khatara Satra observes a wide array of month-based festivals, each deeply rooted in Assamese Vaishnavite tradition.

Apart from the renowned Khatara Satra, Darrang district is home to several other significant Satras such as Dewananda Satra, each playing a vital role in enriching the region’s cultural and spiritual heritage. In the second part of this article, I will delve deeper into these institutions and their unique contributions.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.