Indian ethos, specifically Hindu ethos and its culture and aesthetics, from nāṭyaśāstra onwards, has relied on raising the consciousness of each participant to a subtler more positive sphere away from the drudgery of daily life, thus healing on various levels via storytelling. What is being encouraged today in the name of modernity, is antithetical to our core civilizational principles. If a book or a comic agitates us more than it informs and elevates then it is mere pamphleteering. Or even yellow journalism. A poem for example is cathartic even while it is being recited, via the beauty of its alliterations and its rhythm. It cannot be art and literature, which looks only at social injustices, even while refusing to look at solutions. We Hindus ought to be more active and have our say in cultural matters so that we may preserve what we have and carry them forward to the next generation. It is time we make amends for the years lost.

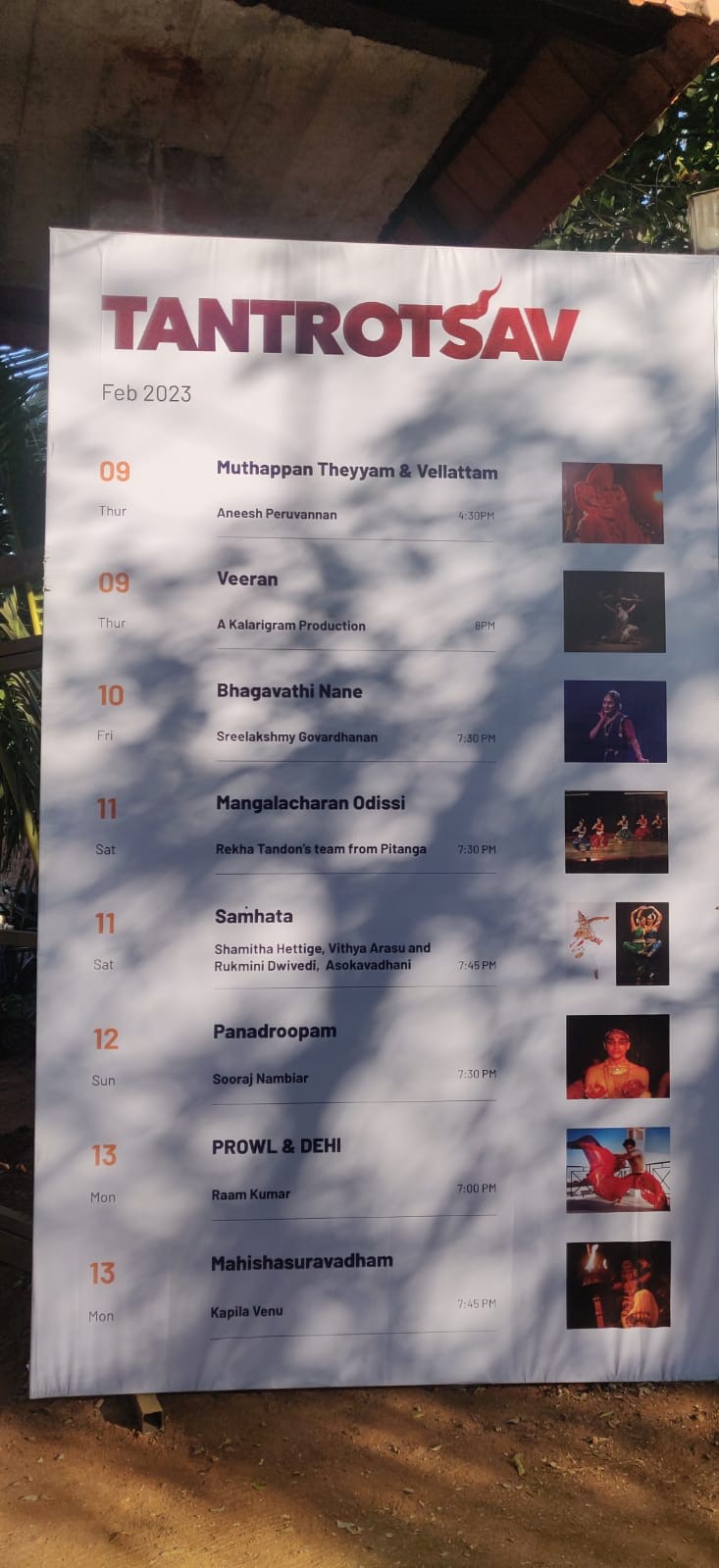

Although bandied about as a ‘Hindu majority nation’ in an accusatory tone even when talking of art and cinema, the truth remains that India that is Bhārat does not have many spaces to call its own, when it comes to showcasing performing arts or even hosting sacred indigenous arts. We might reminisce about a Thakur’s Shantiniketan or a Rukmini Devi’s Kalakshetra fondly, or Protima Bedi’s Nrityagram, but we cannot speak of an iconic space that showcases and platforms all the divine performing art forms under one roof – or open sky. This changed last week when I happened to attend Tantrotsav 2023 at Kaḻarigrām in Auroville. A nine-day long cultural festival that culminates with a grand finale on the auspicious night of Mahāśivarātri, it hosts some of the best artists, dancers, singers and musicians of India (and outside), who gather in this sacred Kaḻari āśrama to showcase and also teach their sacred art forms. It is one of the major events in India’s religious-cultural calendar where the sacred performing art traditions of India are presented with the authenticity and reverence they deserve.

(Figure 1: The Kaḻari pit)

Here then was a Hindu sacred space open to all, as it should be, where one could soak in the glorious traditions of our bhāratīya jñāna paramparā at leisure. Under the early February starlit sky, which at dusk turned madder, with the open flame torches and brass dīyās, with marigold toraṇas keeping company with banana flowers and coconut fronds, with Kerala murals as friezes, with a larger than life Kurumba Bhadrakāli watching all the proceedings with a keen eye, even the aesthetics spoke a different language than what we are usually used to. It calmed the city person and called her in to relax and take a deep breath.

(Figure 2: Kurumba Bhadrakāli)

Hindu aesthetics have yet to become aspirational and we are yet to become unapologetic about something which is so naturally environmentally friendly and organically beautiful. The white kolams on red earth juxtaposed with dexterity invited us to experience various master classes, workshops, performances, and freshly made local cuisine, while serendipitously meeting up with a well known dancer, musician, or artiste who might end up standing next to you in the queue for Kaḻaripayaṭṭu, Kūḍiyaṭṭam, Mohiniaṭṭam, Baul Singing and such like.

The Puraṇas came alive in various rasas – bhakti, vīrya, adbhuta…..some storytellers hardly spoke while they conveyed a whole story and more only with their eyes and eyebrows. Which is what we were privy to during the spectacular Nangyar Kūthu consummately presented by Kapila Venu. An allied art form of Kūḍiyaṭṭam, Nangyar Kūthu is performed solely by women. Kūḍiyaṭṭam is the oldest theatre tradition in the world with a continuous history of at least 900 years. Till recently it was only performed in Hindu temples for Hindus only, before it was opened up for non-Hindu audiences in the mid-20th century, partly due to the ‘social-reform movement’ and partly due to the collapse of Hindu patronage. Most of these programs were without a program note as is normal practice in the West, but it was made all the more sacred due to such spontaneity and lack of wanting to explain oneself to the audience. It kept the surprise element alive and helped us experience it the way it was intended to be, without long drawn explanations, without making art into academics.

(Figure 3: Main building)

While events at the Tantrotsav 2023 were ticketed this year, they have always been free since its inception a decade ago. Why then must the audience be charged now? Well, this expectation that all art must be free for the asking because it is sacred and belongs to all humanity does not answer the question of who will feed the artistes if so? Where is the patronage coming from, now that we have abolished monarchy? We spend frivolously on food and cinema without a second thought but are loathe to buy a Rs.500 ticket to participate in a once in lifetime performance that could give us more lasting joy than a thin crust pizza with choicest toppings. Why do we expect aesthetic pleasure to be free even while doling out cash for gastronomical fulfilment?

The tickets of course meant that there were lesser crowds than usual, but this also meant that people did not show up frivolously for something deep and meaningful with their dates just because it was one more thing ‘to do’ and not because they were genuinely interested or were rasikas. Artistes who train for years before they can appear in public, leading hard disciplined lives, cannot survive on air. Accompanists have to be paid too, so does the hosting space. How will Kaḻarigrām survive, only goodwill is not enough?

That said, it was a beautiful experience all in all running into people of all ages and religions, from various countries, mingling together in this global hotspot. Kaḻarigrām, an offshoot of the Hindustan Kaḻari Sangam of Kozhikode (1952), was started by Laxman Gurukkal (as they are addressed, or as Guruji) more than a decade ago where he could offer Kaḻaripayaṭṭu, Yoga, Meditation and Ayurveda classes. Lakshman Gurukkul, comes from the elite lineage of Kaḻari masters and śākta upāsakas of Kerala. He says that during the ancient times in Kerala, there were universities where the tāntric and yogic sciences, traditional dance, theatre, martial arts, medicine, all were studied and practised together in an institutionalized way. Kaḻarigrām is his vision to revive such an ancient university of our sacred sciences which can also serve as a research university of sorts. He now trains eligible students in a two year diploma in Kaḻaripayaṭṭu, where students need to attend mandatory classes in the early mornings and early evenings, leaving the whole day free for the ‘work from home’ types. A functioning kitchen and rooms are available for students and visitors. A yajña room, a pūja room, a kaḻari pit, an auditorium, an open air temple, under the banyan tree performing space, all this and more comprise Kaḻarigrām.

As per Manish Maheswari, a patron, “Kaḻarigrām is also a centre for the practice of Śākta Hinduism. Practices, rituals, and festivals related to the Śakta tradition are conducted at Kaḻarigrām according to the ancient ritual manuals. The period of Navarātri is especially auspicious as various homas, yajñas and pūjās are performed to propitiate and seek blessing from the supreme Goddess. Kaḻarigrām is constructing an āgamic temple dedicated to the Goddess Bhagawati, who is the patron Goddess of Kaḻaripayaṭṭu and other sacred art forms. Shri Lakshman Gurukkal, the founder of Kaḻarigrām, is an advanced Śri Vidyā practitioner and has initiated many of his advanced students into Śri Vidyā worship. A veritable universe in microcosm, the human body in Kaḻaripayaṭṭu is visualized as a vessel consisting of fiery energy channels called nāḍis and distinct energy centres called cakras. This conception of the human body underlying the practices of Kaḻaripayaṭṭu is derived from the ancient Śaiva-Śakta tāntric tradition of esoteric ritual practices and visualization meditation. Therefore, the non-somatic meditational practices of Śākta Hinduism are complementary to the more somatic practices of Kaḻaripayaṭṭu.” This is reiterated by Maciej Karasinski-Sroka in his paper When Yogi Becomes Warrior (2021) that the goal of any spiritual practice is the ultimate unity of the personal with the universal. In Kaḻaripayaṭṭu too a spiritual empowerment along with the awakening of the body is sought to be achieved by the practitioners. Kaḻarigrām, then, is a modern experiment to create a space where the relentless secularization and rationalization of all forms of our modern life are put on hold, and the senses are allowed to explore those realms of thoughts and feelings which are inaccessible to us in our day-to-day lives.

Kaḻaripayaṭṭu as explained in this article by Sai Priya Chodavarapu is as much a spiritual practice as it is a body technique, and a martial arts form. It is simultaneously a yoga routine that includes both, dhyāna and prāṇāyāma. Its effect on the sūkśma śareera is well documented. Hence it is a sādhanā which has the capacity to transform the person who is undertaking it with śraddhā. Kaḻari includes all aspects of nāṭyam in it except perhaps abhinaya. Here, as in any gurukulam, the gurus test the eligibility of the students before accepting them in their fold, and for taking them to the next level. This eligibility is patience and perseverance, as well as stamina and sustenance. Satyanarayan Gurukkal who was invited to present a Masterclass on the Northern Style of Kaḻari described beautifully the guru-śiṣya paramparā that is very much alive in teaching Kaḻaripayaṭṭu, and how it was being taken forward.

(Figure 4: Masterclass by Satyanarayan Gurukkal)

At Kaḻarigrām I was witnessing for the first time performing arts which was not catering to an outsider or a western lens, which was not proclaiming to be woke or trying to solve a social problem or issue, but was merely exhibiting itself in all its authenticity. Here is a space that does not fall into the trap of the oppressor-oppressed but elevates us to the higher sublime realms via its aesthetics. Here is where the sacred and sensuous meet, where the parā and the aparā fuse together in oneness and help us release our burdens in that aikyam. Here we are neither guilty nor hurting, we are neither complaining nor dismantling, we simply are! Here we allow art to be redemptive and therefore revel in that ānanda.

Attempts are being made slowly to understand, appreciate, and reclaim our sacred spaces, our streets, and our stages with performances that speak of our lived experiences of a millenia, that tells the stories of our epics and our ancestors. Be it Gudiya Sambhrama in Bengaluru or Tantidhari at Sanatan Siddhashram these are but few attempts to undo an oversight which has to be rectified immediately. For Hindus, arts and aesthetics is yet another means to connect to the divine. It is not a vehicle to vent our worldly woes in but to transcend with its aid to realms beyond. Tantrotsav a yearly offering at Kaḻarigrām, welcomes us to do just that in its one of a kind space.

As per Dr. Sharda Narayanan in “The Tradition Of Natya: Position And Development Of Natya In Sanskrit Tradition (Part 3: Rasa Experience in Indian Aesthetics”: “Abhinavagupta has clearly stated that this feeling of joy or thrill or bliss cannot be explained by any of the pramāņas, or means to valid knowledge, of the rational world. This is the chief reason that it is called alaukika, or beyond the mundane world of everyday transactions. The rasika loses the sense of time and space of personal existence and merges with the world that is staged. The rasa experience transcends the normal world of daily existence in terms of personal involvement, profit and loss, or cause-and-effect equations. The situation may be unreal, staged, but the emotional response is real”

(Figure 5: Festive décor)

For Imran Sarfaraz, a strength and conditioning coach in Mumbai; Carolina Prada, a Colombian Mayurbhanj Chau dancer; Pooja Vedvikhyat, an NSD graduate, and many more from all over the country and the world, who chose to invest their time and energies at Kaḻarigrām, the wholesome mentoring and training that they acquire here brings them back year after year. And thanks to their own personal motivations and emotional fulfilment, we may see this space flourishing as it should, setting a fine example and birthing more such.

NOTE: This experience was made possible due to the generous sponsorship by IndicA.

Image Credit: Kavita Krishna Meegama

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.