A Philosophical Analysis of Non-Objectifiability and Cognitive Collapse in the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa

Abstract

This paper offers a philosophical analysis of three conceptual structures embedded within the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa: (1) Sītā as a narrative embodiment of non-objectifiable liberation (mokṣa), (2) Rāma as aligned agency, and (3) Rāvaṇa as the exemplary case of ‘partial consciousness’ – a condition in which ritual accomplishment, intellectual attainment, and metaphysical power coexist with fundamental misalignment, resulting in catastrophic moral and cognitive collapse.

Drawing on the Sanskrit epic tradition and secondary scholarship in Indian philosophical hermeneutics, this study argues that Rāvaṇa’s downfall represents not merely moral failure but structural instability: the attempt to objectify consciousness itself. The article introduces the technical term khaṇḍa-caitanyam (‘partial consciousness’) as a contemporary philosophical coinage to describe this phenomenon and demonstrates that this pattern appears universally across human civilizations, professions, and religious traditions, making it a valuable framework for understanding ethical collapse.

By examining the epic’s narrative architecture, this study reframes the Rāmāyaṇa’s ethical and metaphysical insights as a coherent philosophical treatise on consciousness, misalignment, and the inevitable collapse that follows when power outpaces wisdom.

Keywords: Rāmāyaṇa; consciousness; mokṣa; partial consciousness; Indian philosophy; ethics; Rāvaṇa; Sītā; non-objectifiability; cognitive collapse

1. Introduction

The Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa has long been studied as a text of kingship, dharma, aesthetics, and devotion (Goldman 1984–2009; Brockington 1998). Far less explored is its internal philosophical architecture concerning consciousness states and their stability. This article examines a specific interpretive thesis: that Sītā, Rāma, and Rāvaṇa represent three distinct states of consciousness within an implicit metaphysical framework.

The Rāmāyaṇa, I argue, encodes three distinct consciousness states—non-objectifiable liberation (Sītā), aligned agency (Rāma), and partial consciousness (Rāvaṇa)—and Rāvaṇa’s downfall is best understood not as divine punishment but as structural collapse caused by cognitive misalignment. This model, I propose, has universal application beyond its cultural origins.

Such a reading does not assume the theological truth of the characters but interprets them as philosophical constructs embedded in the narrative. While classical commentators such as Govindarāja, Mādhava Yogin, and the authors of the Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇa develop theological or devotional interpretations, this paper adopts a strictly conceptual approach consistent with contemporary methods in Indian philosophy studies (Pollock 2006; Olivelle 1998; Freschi 2012).

The central thesis of this paper is threefold. First, regarding the ancient framework: Rāvaṇa fails not because he is immoral, but because he is misaligned; he collapses because partial consciousness—however powerful—is structurally unstable. Sītā cannot be captured because liberation cannot be objectified. Second, regarding the universal pattern: this ‘Rāvaṇa-architecture’ of partial consciousness appears across all civilizations, professions, and religious traditions wherever knowledge, power, and recognition concentrate without full-spectrum consciousness integration. Third, regarding contemporary relevance: this ancient philosophical insight provides a diagnostic framework for understanding modern institutional and individual failures across all domains of human excellence.

2. Terminological Clarification: Khaṇḍa-caitanyam

The term khaṇḍa-caitanyam, used throughout this article to describe Rāvaṇa’s cognitive condition, is a deliberate contemporary coinage, not an attested technical term in classical Sanskrit philosophical literature. However, its conceptual structure is firmly anchored in classical categories. In Advaita traditions, impaired or distorted cognition is typically described through terms such as avidyā (misapprehension of the real), bhrānti (cognitive error), viparyaya-jñāna (inverted or mistaken knowledge), āvaraṇa (veiling), and vikṣepa (projective distortion).

While these denote forms of cognitive obstruction, they do not fully capture the specific structural phenomenon this article seeks to describe: the coexistence of extraordinary cognitive capability with systemic misalignment across ethical, introspective, and ontological domains. Khaṇḍa-caitanyam therefore refers to a fragmented or non-integrated consciousness state—one in which knowledge is extensive but lacks unifying orientation, self-awareness, and ethical coherence. It differs from avidyā by emphasizing partial illumination rather than complete ignorance, differs from bhrānti by foregrounding structural instability rather than discrete errors, and differs from āvaraṇa by denoting a divided, multi-directional consciousness rather than simple obscuration. The term thus provides a precise analytical category for understanding how Rāvaṇa’s profound learning and ritual mastery could coexist with catastrophic moral and metaphysical misjudgment, culminating in inevitable collapse.

3. Literature Review

3.1 Classical Philological Scholarship

Scholars have noted the epic’s layered composition (Goldman 1984–2009) and its overarching concern with dharma and kingship (Brockington 1998). Yet the text also engages deeply with metaphysical themes familiar in Upaniṣadic discourse—identity, non-duality, suffering, and the nature of the self.

3.2 Philosophical Studies of the Rāmāyaṇa

There is an emerging body of scholarship treating the epic philosophically rather than mythologically (Freschi 2012). However, few studies analyze Sītā as a conceptual category of non-objectifiability or interpret Rāvaṇa’s downfall as cognitive collapse rather than moral degeneration. The present study addresses this scholarly gap through sustained philosophical investigation.

3.3 Ritual Power, Knowledge, and Misalignment

Indian philosophical discourse frequently critiques the limits of ritualism (karmakāṇḍa) and knowledge unaccompanied by self-awareness (jñāna-bandha). Texts such as the Kaṭha Upaniṣad and Yogavāsiṣṭha emphasize that ascetic merit without alignment is dangerous (Olivelle 1998). Rāvaṇa fits precisely into this theoretical space.

3.4 Contemporary Cognitive Science and Ethics

Modern research confirms that exceptional ability does not correlate with ethical clarity or emotional regulation (Tangney, Stuewig, and Mashek 2007; Rest 1986). Highly capable individuals in every domain may exhibit the Rāvaṇa-profile: excellence in one dimension and blindness in another.

4. Methodological Framework

This study employs the following methodological approaches: phenomenological analysis of consciousness states represented in the text; conceptual hermeneutics following Ganeri (2013); philological grounding in the Sanskrit epic tradition; internal textual reasoning, avoiding theological commitments; and comparative structural analysis examining modern parallels. The reading is non-sectarian and purely analytic, treating ancient narrative and contemporary cases as instances of the same structural pattern.

5. Sītā as Embodiment of Non-Objectifiable Liberation

5.1 Sītā’s Nature as Mokṣa-svarūpiṇī

I propose that Sītā functions in the epic not primarily as a person but as a svarūpa (essential nature) of liberation itself. The Sanskrit formulation would be: na sītā vyaktirevāsti mokṣasya tu svarūpiṇī / agṛhyā sā svabhāvena yathā ātmā na gṛhyate—’Sītā is not merely a person, but the very form of liberation. Ungrasped by nature, just as the Self cannot be grasped.’ This establishes the philosophical foundation: Sītā represents a state (avasthā), not an entity (vastu).

5.2 Birth from the Earth as Philosophical Motif

In the Bālakāṇḍa of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, Sītā is discovered in a furrow during ploughing (Rām. 1.66). The text does not describe childhood, growth, or apprenticeship. She enters the narrative already complete. If Sītā represents already-complete liberation, childhood would be conceptually incoherent because liberation is not achieved progressively but is recognized. Her narrative structure—sudden, complete emergence—mirrors the Upaniṣadic metaphor of the sun behind clouds: always present, only uncovered.

In classical Indian philosophy, such emergence aligns with the idea that liberation is not produced (kṛta), earned (ārjita), or granted (prasādita), but uncovered (āvirbhūta) (Olivelle 1998). Sītā is not an evolving aspirant but a representation of a completed state (siddhāvasthā).

5.3 Immunity to Objectification

Across the Araṇyakāṇḍa, Sundarakāṇḍa, and Yuddhakāṇḍa, Sītā cannot be seduced, cannot be coerced, cannot be possessed, and cannot be mentally destabilized. The philosophical interpretation suggests: na śakyā bhīṣaṇenāpi na dānena na māyayā / mokṣaḥ svatantrabhāvaḥ syāt kathaṃ taṃ paravaśyatām—’Not by terror, not by gifts, not by illusion can she be swayed. Liberation is independence by nature—how can it be made dependent?’

This matches a core Upaniṣadic claim: ‘The Self is not seized by the mind’ (manasā na gṛhyate, Kaṭha Upaniṣad 1.2.12). The narrative constructs Sītā as a phenomenological category: what cannot be captured.

6. Rāma as the Principle of Alignment

This paper does not treat Rāma as deity but as a narrative representation of perfectly aligned agency. The philosophical description would be: samīkṛtacitto rāmaḥ dharmajñānakriyāsamaḥ / na viṣayeṇa vicalati na dharmāt ca kadācana—’Rāma, whose mind is aligned, equal in dharma, knowledge, and action. Never swayed by objects, never departing from dharma.’

Key characteristics include: adherence to dharma, freedom from reactive impulses, balance between emotion and reason, capacity for right action under complexity, and ability to recognize Sītā’s intrinsic nature. Rāma’s role is not to grant liberation but to attune to it. He exemplifies the proper orientation toward consciousness: neither controlling nor rejecting, but recognizing.

The crucial point is that Rāma recognizes rather than achieves Sītā: na labdhā rāmeṇa sītā na jitā na ca rakṣitā / pratyabhijñātā kevalaṃ svarūpeṇa yathā sthitā—’Sītā is not obtained by Rāma, not conquered, not protected. Only recognized in her essential nature as she abides.’ This establishes the philosophical relationship: aligned consciousness recognizes liberation without attempting to possess it.

7. Rāvaṇa: The Full Arc of Attainment and Collapse

7.1 The Central Philosophical Question

The philosophical investigation opens with a fundamental question: kiṃ tat yasya viśālajñānaṃ mahattapaḥ kṣamā / tathāpi patanaṃ yāti kimetat kāraṇaṃ bhavet—’What is that by which one possessing vast knowledge, great austerity, and capability nevertheless falls? What could be the cause of this?’

Rāvaṇa is one of the most intellectually and ritually accomplished figures in Sanskrit literature. The Uttarakāṇḍa and epic references attribute to him: mastery of the Vedas, knowledge of sixty-four arts (kalās), authorship of philosophical treatises, profound musical knowledge, immense ritual power acquired through tapas, cosmic weapons from Brahmā, and sovereignty over Laṅkā, one of the most advanced realms in the epic tradition. Yet he experiences total collapse.

7.2 Ascetic Attainments and Acquisition of Power

The Uttarakāṇḍa offers the most detailed account of Rāvaṇa’s austerities, describing an ascetic program of extraordinary severity culminating in significant ritual merit and cosmic boons. Rāvaṇa performs tapas of increasing intensity, each stage marked by an act of self-offering that compels Brahmā to appear and grant him unparalleled powers.

The philosophical interpretation suggests: tapasā śaktivardhanaṃ na tu cittapariśuddhiḥ / balaṃ vinā bodhaṃ yathā astraṃ vinā vivekam—’Through austerity, power increases, but not purification of mind. Like strength without wisdom, like weapons without discrimination.’ This envisions ritual power as accumulable independent of moral orientation—a theme aligned with early Upaniṣadic concerns about the limits of ritual efficacy. Importantly, the narrative emphasizes gradual empowerment without corresponding transformation of consciousness, reinforcing the philosophical point that Rāvaṇa’s attainment is expansive in capacity but stagnant in alignment. His tapas enhances his instrumental power (śakti) but leaves untouched the distortions of ego (ahaṃkāra) and desire (kāma) that ultimately precipitate collapse.

7.3 The Ten Heads as Fragmented Knowledge

The depiction of Rāvaṇa with ten heads (daśānana) has generated extensive symbolic interpretations in later philosophical and pedagogical literature (De 1976). I propose treating this as a hermeneutic model of fragmented consciousness. The interpretation would be: daśa mukhāni daśa vidyāḥ pṛthak pṛthak viśāradāḥ / na tu ekīkṛtasaṃjñānaṃ vibhaktaṃ jñānamasthiram—’Ten heads are ten sciences, separately mastered. But without integrated understanding, divided knowledge is unstable.’

Under this framework, the ten heads represent ten distinct knowledge domains, each cultivated to a high degree but lacking integrative coherence. This reflects a condition recognized in multiple śāstric traditions: jñāna-bheda—the fragmentation of knowledge that prevents holistic self-understanding. The daśamukha form becomes a conceptual device signifying multiplication of cognitive capacity without unity of purpose, breadth without depth of self-knowledge, information without integration, and mastery without introspective clarity.

The philosophical formulation captures this: bahuvidyo vinā ekatvaṃ yathā nagaraṃ vinā rājā / asambaddhajñānarāśiḥ patanāya pravartate—’Many-knowledged without unity, like a city without a king. A heap of unconnected knowledge proceeds toward collapse.’ This reading is supported by Rāvaṇa’s conduct: he is capable of profound discourse, composes music and philosophical treatises, debates effectively with ministers and adversaries, yet he is unable to regulate desire or assess moral boundaries.

7.4 Intellectual Attainment Without Alignment

The epic repeatedly describes Rāvaṇa’s vast knowledge. The philosophical analysis identifies three limitations: instrumentalization of learning (knowledge as power, jñānaṃ balāya), egoic identification with learning (knowledge as self-image, jñāna-ahaṅkāraḥ), and absence of self-knowledge (lack of reflective insight, ātmajñāna-abhāvaḥ). He embodies śabda-jñāna (verbal knowledge) without ātma-jñāna (self-knowledge), a classical distinction (Olivelle 1998).

The diagnosis is captured in the formulation: śāstrajño nātmavettā yaḥ sa bhāravāhī na muktidīḥ / rāvaṇo bahuvidvān api ātmānaṃ na veda saḥ—’One who knows scriptures but not the Self is a burden-bearer, not liberation-minded. Rāvaṇa, though multi-knowledgeable, does not know himself.’

7.5 Moral Transgressions and Boundary Violations

Rāvaṇa’s abduction of Sītā is not merely moral failure but, philosophically, a category error. The analysis suggests: mokṣaṃ vastutve na matvā haraṇaṃ kṛtavān asau / caitanyaṃ caitanyena kathaṃ gṛhṇīyāt kadācana—’Thinking liberation to be an object, he attempted abduction. How can consciousness ever grasp consciousness?’

This represents: treating liberation as object (vastukalpanā), believing consciousness can be possessed (caitanya-grahaṇa), assuming ritual merit confers ontological entitlement (tapo’dhikāra), and confusing power with alignment (bala-samyaktva-bhrānti). This error becomes the fulcrum of his collapse.

7.6 The Cognitive Mechanics of Partial Consciousness

The epic represents Rāvaṇa as a mind divided. The phenomenological analysis identifies: extensive intellectual capacity (vipulabuddhiḥ), intense desire (tīvrakāmaḥ), inflated ego (vṛddhāhaṅkāraḥ), and oscillation between insight and delusion (viveka-moha-vibhrāntiḥ).

Partial consciousness (khaṇḍa-caitanyam) is defined thus: yatra śaktiḥ vardhate buddhiśca vistaraṃ yāti / na tu ātmajñānaṃ nītibodho vā samavardhate // tat khaṇḍacaitanyaṃ proktaṃ asthiraṃ patanonmukham—’Where power increases and intellect expands, but self-knowledge and ethical understanding do not equally grow, that is called partial consciousness—unstable and collapse-prone.’ This model parallels Indian philosophical critiques of asceticism without self-awareness (ātmajñāna-hīna tapas).

Such a state is structurally unstable because: power amplifies misalignment (balaṃ vibhedaṃ vardhayati), desire intensifies with capacity (śaktyā kāmo jāyate), ego increases with recognition (pratisthayā ahaṅkāraḥ), and boundary violations escalate (sīmālaṅghanā vṛddhiḥ). Thus collapse is not punishment but an inherent outcome (svabhāvika-phalam).

7.7 The Attempt to Capture Sītā as Philosophical Error

The central error (sītā-grahaṇa-bhramāḥ) receives extensive analysis: sītāṃ gṛhītuṃ yaḥ prayāsaḥ sa mithyāprayatnaḥ syāt / muktiṃ kathaṃ bandhayet kaḥ svataṃtraṃ paravaśyatām—’The effort to grasp Sītā is a false effort. How can one bind liberation? How can one make the independent dependent?’

Rāvaṇa’s central mistake is metaphysical, not strategic. He assumes that Sītā is an object (vastu), that objects can be possessed (vastuni svāmyaṃ sambhavati), and that possession indicates victory (grahaṇaṃ jayaḥ). But liberation (mokṣa) is inherently non-objectifiable: it cannot be taken (agṛhya), it cannot be confined (abandhya), it cannot be threatened (abhayya), it cannot be controlled (aniyamtrya). Therefore, his effort is structurally impossible (asambhāvya-prayatnaḥ).

The philosophical formulation illustrates this: yathā ākāśaṃ ghaṭena kaḥ saṃgrahītuṃ samarthaḥ syāt / tathā mokṣaṃ manobuddhyā na śakyaṃ parikarṣitum—’Just as no one can capture space with a pot, so liberation cannot be drawn in by mind or intellect.’

8. The Progressive Collapse: A Six-Phase Model

I propose understanding Rāvaṇa’s collapse as a systematic philosophical progression (krama-patana-vicāraḥ), not a random punishment. Each phase is analyzed with Sanskrit terminology.

Phase 1: Phūtkāra-avasthā (Inflation). When accomplishment comes, the ‘I’ increases—’my austerity, my knowledge, all this is mine’ (yadā siddhiḥ āgacchati tadā ahamiti vardhate / mama tapaḥ mama jñānaṃ mamedaṃ sarvamityapi). Success generates ego-identification (aham-māna), which reduces capacity for self-critique (ātma-vimarśana-kṣīṇatā).

Phase 2: Sīmā-bhaṅgaḥ (Boundary Erosion). When discernment is conquered by desire, then all boundaries begin to be transgressed (vivekaḥ kāmena parājito yadā / tadā sarve sīmāḥ laṅghayituṃ pravartante). Ministers’ warnings (mantri-upadeśāḥ) are dismissed as jealousy (īrṣyā) rather than wisdom (prajñā).

Phase 3: Dvandva-avasthā (Cognitive Dissonance). Sometimes knowledge flashes for a moment; again covered by delusion, he proceeds toward collapse (kadācit jñānasya prakāśaḥ bhavati kṣaṇam / punaḥ mohena āvṛtaḥ saḥ patanaṃ prati gacchati). Mandodari’s warnings represent moments of clarity that cannot penetrate the structure of contaminated consciousness.

Phase 4: Vastu-kalpanā (Ontological Misidentification). This is the critical philosophical error: seeing liberation as woman, imagining it as object, thinking ‘graspable,’ he attained great delusion (mokṣaṃ strītvena dṛṣṭvā vastutve na ca kalpitam / grahaṇīyamiti matvā mahābhrāntiṃ prāptavān asau). Sītā—representing liberation-consciousness—is reduced to an object of possession. This category confusion (jāti-bhrānti) is the fulcrum of collapse.

Phase 5: Anivārya-patanam (Inevitability of Collapse). Power without alignment cannot stand long, like a tree without roots, destined for collapse (śaktiḥ vinā samīkaraṇaṃ na sthātuṃ śaknoti ciram / yathā vṛkṣaḥ vinā mūlaṃ patanāya bhavet tathā). The structure cannot sustain the internal contradiction. This is not moral punishment but structural necessity (saṃracana-niyatiḥ).

Phase 6: Vināśaḥ (Destruction). The death is framed philosophically: this killing is not mere slaying but resolution of contradiction; this is the natural consequence of partial consciousness itself (na hananaṃ kevalaṃ vadhaḥ ayaṃ virodhasya samādhānam / khaṇḍacaitanyasya svabhāvapariṇāmaḥ eva eṣaḥ). The epic frames his death not as defeat (parājaya) but as resolution of contradiction (virodha-samādhāna).

9. The Principle of Non-Objectifiability

Drawing on Upaniṣadic principles, I propose that liberation is: not produced, not earned, not given, not transformed—self-revealed, always accomplished by nature (na kṛtaṃ na arjitaṃ na dattaṃ na parivartitam / āvirbhūtaṃ svayaṃ muktiḥ sadā siddhā svabhāvataḥ).

The properties of non-objectifiable liberation have direct implications for Rāvaṇa: liberation being not produced (akṛta) means his power cannot create it; being not earned (anārjita) means his tapas cannot purchase it; being not transferable (apahārya) means abduction is meaningless; being not modifiable (aparivartya) means threats cannot affect it; being self-revealing (āvirbhūta) means it requires recognition, not acquisition; being always accomplished (nitya-siddha) means there are no progressive stages.

The Rāmāyaṇa uses Sītā to illustrate this principle narratively. Her immunity in Laṅkā is not supernatural; it is philosophical: what is free by nature cannot become dependent; how could Sītā, whose form is liberation, ever be bound? (svatantraṃ svabhāvena yat tat paratantraṃ na bhavitum / sītā mokṣasvarūpiṇī kathaṃ baddhā bhavet kadā). Thus, Rāvaṇa’s failure is inherent: he attempts to dominate what cannot be dominated (aśakyaṃ śakyaṃ kartum).

10. The Universal Pattern of Partial Consciousness

The philosophical framework developed above is not culturally limited. This ‘Rāvaṇa-architecture’ of partial consciousness appears across civilizations, professions, and religious traditions wherever knowledge, power, and recognition concentrate without full-spectrum consciousness integration.

Contemporary psychological research supports this model. Studies on moral licensing suggest that prior good behavior can paradoxically license subsequent unethical action (Merritt, Effron, and Monin 2010). Research on hubris syndrome identifies a pattern where leaders with extensive capability develop impaired judgment and contempt for others’ opinions (Owen and Davidson 2009). Work on ethical fading shows how self-deception allows people to behave unethically without recognizing the ethical dimension of their actions (Tenbrunsel and Messick 2004). Research on moral disengagement demonstrates how people selectively disengage moral self-regulation to permit harmful conduct (Bandura 2002).

This pattern appears in scientific institutions where research excellence coexists with ethics violations, in religious leadership where spiritual authority combines with abuse, in political leadership where strategic brilliance accompanies moral failure, in business where innovation capability coincides with exploitation, and in intellectual fields where philosophical sophistication occurs alongside personal misconduct. In each case, the Rāvaṇa-pattern is evident: extraordinary capability in one domain with profound blindness in ethical self-assessment.

11. Philosophical Implications

11.1 The Problem of Power-Knowledge Asymmetry

The analysis reveals a fundamental philosophical problem: how can extraordinary knowledge coexist with ethical blindness? The answer lies in the structure of partial consciousness. Knowledge accumulation without integration creates cognitive silos. Power amplifies the capacity for both benefit and harm. Success generates ego-identification that impairs self-critique. Achievement creates illusions of general competence that extend beyond actual domains of expertise.

The Rāvaṇa case demonstrates that this is not a moral failing that can be corrected by exhortation but a structural condition requiring specific interventions: cultivation of self-knowledge (ātma-jñāna) alongside other forms of knowledge, integration of knowledge domains rather than mere accumulation, maintenance of structures that provide honest feedback, and recognition that capability in one domain does not transfer to ethical judgment.

11.2 The Ethics of Responsibility

Hans Jonas’s imperative of responsibility (Jonas 1984) argues that increased power demands proportionally increased responsibility. The Rāvaṇa model adds a crucial dimension: responsibility is not merely an obligation but a structural requirement. Power without corresponding ethical development is inherently unstable and will collapse. This is not moral judgment but structural analysis.

11.3 The Problem of Self-Knowledge

The analysis raises fundamental questions about self-knowledge. How can partial consciousness recognize its own partiality? The epic suggests that Mandodari and other advisors provide moments of clarity that Rāvaṇa cannot integrate. This points to the necessity of external feedback structures for self-knowledge—the individual alone cannot overcome structural blindness.

Research on moral emotions confirms this: shame, guilt, and embarrassment serve regulatory functions that require social context (Tangney, Stuewig, and Mashek 2007). The Rāvaṇa model suggests that isolated consciousness, however capable, cannot correct its own distortions. The cultivation of reciprocal consciousness (paraspara-caitanyam)—mutual awareness and feedback—becomes essential.

12. Structural Safeguards Against Partial Consciousness

Given the structural nature of partial consciousness, individual moral effort alone is insufficient. The analysis suggests several categories of structural safeguards.

First, knowledge integration (jñāna-aikīkaraṇam): rather than accumulating knowledge in separate domains, emphasis should be placed on integration, particularly of technical knowledge with ethical understanding and self-awareness. Second, structural feedback mechanisms: institutions should build in robust channels for honest feedback that cannot be dismissed as jealousy or ignorance. Third, power-responsibility coupling: increases in power should be accompanied by proportional increases in accountability and oversight. Fourth, cultivation of reciprocal consciousness: systems should foster mutual awareness rather than isolated excellence. Fifth, recognition of limits: explicit acknowledgment that expertise in one domain does not transfer to others, particularly ethical judgment.

13. Conclusion

This study has proposed a philosophical framework for understanding three consciousness states encoded in the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa: Sītā as non-objectifiable liberation (mokṣa), Rāma as aligned consciousness (samyak-caitanya), and Rāvaṇa as partial consciousness (khaṇḍa-caitanya). The central philosophical claim is that partial consciousness—however powerful—is structurally unstable, and that the attempt to objectify liberation inevitably results in collapse.

The term khaṇḍa-caitanyam has been introduced as a contemporary philosophical coinage to capture a phenomenon inadequately described by classical terms like avidyā or bhrānti: the coexistence of extraordinary cognitive capability with systemic ethical misalignment. This condition is characterized by fragmentation of knowledge without integration, power amplification without corresponding wisdom, and structural instability that necessarily tends toward collapse.

The universal applicability of this pattern has been demonstrated through references to contemporary psychological research on moral licensing, hubris syndrome, ethical fading, and moral disengagement. The pattern appears wherever humans achieve power without corresponding wisdom—in science, religion, politics, business, and intellectual life.

This re-reading contributes to contemporary Indian philosophy and universal ethical discourse by demonstrating that the Rāmāyaṇa emerges not as mythology but as sophisticated investigation into consciousness states, their stability, and their collapse patterns. The ancient framework provides tools directly applicable to contemporary institutional failures, professional ethics crises, and personal development.

The philosophical formulation captures the essence: khaṇḍacaitanyaṃ pūrṇacaitanyaṃ dhārayituṃ na śaknoti / rāvaṇaḥ sītāṃ grahītuṃ na śaknoti mokṣo’gṛhya eva—’Partial consciousness cannot hold complete consciousness. Rāvaṇa cannot grasp Sītā because liberation cannot be grasped.’

Every field, every profession, every institution—and indeed every individual—faces what might be called the Rāvaṇa-test: will power corrupt, or will alignment prevail? The answer lies not in condemnation but in constant vigilance, structural safeguards, and the cultivation of reciprocal consciousness at every level of human organization. The choice, as the philosophical tradition suggests, stands before each person in each moment.

References

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119.

Brockington, J. (1998). The Sanskrit epics. Brill.

De, S. K. (1976). Early history of the Vaiṣṇava faith and movement in Bengal. Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

Freschi, E. (2012). What is Indian philosophy? Philosophy East and West, 62(4), 531–557.

Ganeri, J. (2013). The self: Naturalism, consciousness, and the first-person stance. Oxford University Press.

Goldman, R. P. (Ed.). (1984–2009). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An epic of ancient India (Vols. 1–6). Princeton University Press.

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Pantheon Books.

Jonas, H. (1984). The imperative of responsibility: In search of an ethics for the technological age. University of Chicago Press.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral self-licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344–357.

Olivelle, P. (1998). The early Upaniṣads: Annotated text and translation. Oxford University Press.

Owen, D., & Davidson, J. (2009). Hubris syndrome: An acquired personality disorder? A study of US Presidents and UK Prime Ministers over the last 100 years. Brain, 132(5), 1396–1406.

Pollock, S. (2006). The language of the gods in the world of men: Sanskrit, culture, and power in premodern India. University of California Press.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Moral development: Advances in research and theory. Praeger.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Messick, D. M. (2004). Ethical fading: The role of self-deception in unethical behavior. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 223–236.

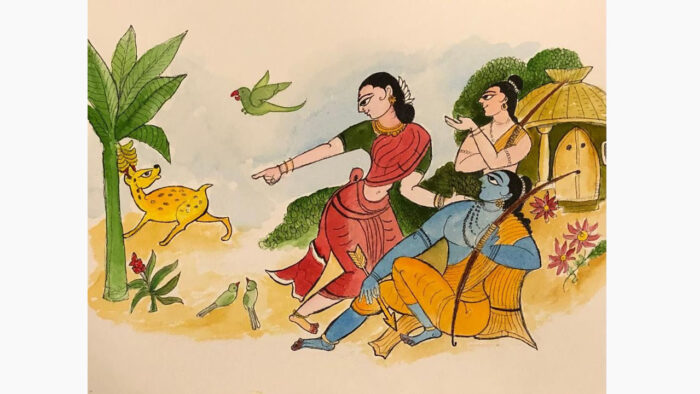

Feature Image Credit: pinterest.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.