Introduction: The Persistent Category Error

A familiar modern question is repeatedly posed to Indian intellectual traditions, often with an air of finality: Where are the experiments in Indian philosophy?

The question appears decisive. Yet it rests on a fundamental category error. We do not ask whether the scientific method itself performs experiments; we ask whether physics, chemistry, medicine, or biology do. The method frames inquiry; the sciences execute it.

Indian Knowledge Systems were architected with this distinction as a foundational principle. Darśanas were never intended to function as laboratories, just as the scientific method was never intended to function as an experimental practice. To demand experimentation at the level of darśana is therefore to mislocate evidence and misunderstand function.

This misunderstanding has shaped many contemporary comparisons between Indian knowledge and modern science. Darśanas are frequently judged by standards that properly belong to applied disciplines, leading to the mistaken conclusion that Indian thought lacked empirical rigor. In reality, the problem lies not in the absence of evidence, but in asking for it at the wrong epistemic level.

Scholars of Indian philosophy and comparative science have repeatedly pointed out this confusion. Frits Staal has shown that Indian intellectual traditions developed highly formalised disciplines governing correctness, transmission, and validation of knowledge, without equating scientific rigour exclusively with laboratory experimentation. The modern tendency to identify “science” solely with experimental practice, Staal argues, is a historically contingent European development rather than a universal criterion of rational inquiry. Similarly, Bimal K. Matilal demonstrated that classical systems such as Nyāya are best understood as normative frameworks of reasoning and justification, not as empirical sciences concerned with producing observational data. Evaluating them by experimental standards, therefore, misconstrues their intended function.

Building on these insights, recent work has reconstructed Indian Knowledge Systems as a layered epistemic architecture, in which intellectual functions are distributed rather than collapsed. In this reconstruction, mechanisms of transmission (such as the Vedāṅgas), validation (Nyāya), and ontological inquiry (the darśanas) operate as distinct but interrelated layers, each governing a specific aspect of knowledge production and assessment (Garikapati 2025). This layered structure enables empirical practice without scientism and pluralism without relativism.

From this perspective, Indian Knowledge Systems are best understood as a two-layer epistemic architecture. At one level operate the darśanas—foundational, domain-specific meta-methodological frameworks that define valid means of knowledge (pramāṇa), legitimate domains of inquiry (viṣaya), conditions of error (doṣa and bādhā), and epistemic closure (nigrahasthāna). At another level operate the śāstras—applied disciplines that instantiate these governing principles through observation, experimentation, procedural refinement, and historical accumulation.

A one-to-one comparison with modern science is therefore meaningful only at the level of śāstras, not darśanas. Far from being unscientific, this separation reflects a level of methodological clarity that modern science itself has largely left implicit. By clearly distinguishing epistemic governance from evidentiary execution, Indian knowledge systems avoided both the overextension of method and the confusion of domains.

Seen through this lens, many contemporary debates dissolve—not because evidence is denied, but because it is placed where it belongs.

The Scientific Method as Meta-Method

Popular accounts often describe the scientific method as a sequence of activities—observation, hypothesis, experiment, and conclusion. While pedagogically useful, this description obscures a more fundamental point. The scientific method itself does not observe, experiment, or collect data. Scientists do. The method governs how inquiry ought to proceed; it does not execute inquiry.

At its core, the scientific method consists of normative constraints. It specifies what counts as admissible evidence, how inference may legitimately proceed, how error is to be identified, when revision is required, and under what conditions a claim may be provisionally accepted or finally abandoned. These are not empirical operations but rules that regulate empirical operations.

The concept of falsifiability illustrates this distinction clearly. Falsifiability does not conduct experiments, generate observations, or accumulate historical data. It functions as a regulative principle: a demand that claims be exposed to the possibility of error. Experiments and observations are among the means by which falsification may occur, but they are not identical with falsifiability itself. To conflate the two is to mistake governance for execution.

Modern science operates with such a meta-method largely implicitly. Philosophy of science attempts to reconstruct this layer retrospectively, treating it as an external reflection on scientific practice rather than as an internal component of the scientific enterprise itself. As a result, the distinction between method and application often remains blurred, and scientific rigor is frequently identified—incorrectly—with experimental practice alone.

Indian Knowledge Systems, by contrast, internalised this distinction from the outset.

Darśanas as Explicit Meta-Methodological Frameworks

Darśanas are frequently presented in modern accounts through categories inherited from European intellectual history—as speculative metaphysics, ethical worldviews, or as part of the prehistory of scientific rationality—rather than as autonomous frameworks governing inquiry. As Wilhelm Halbfass has shown, this framing has deep roots in Greek and later European receptions of Indian thought, where Indian traditions were assimilated to familiar philosophical schools, treated as anticipatory backgrounds to Greek philosophy, and evaluated primarily through external disciplinary concerns rather than their own epistemic self-understanding (Halbfass 1988). These descriptions miss their intended function. Darśanas are not competing theories of the natural world, nor are they incomplete sciences. They are explicit frameworks governing inquiry itself.

Each darśana specifies, with remarkable precision, the conditions under which knowledge claims can be meaningfully made and assessed. These specifications include the recognition of valid means of knowledge (pramāṇa), the delimitation of legitimate domains of inquiry (viṣaya), the clarification of the purpose of knowing (prayojana), the identification of error and overreach (doṣa and bādhā), the use of tarka to test competing positions, the procedure of nirṇaya for establishing siddhānta, and the specification of failure conditions that expose untenable claims (nigrahasthāna). These are not empirical propositions about the world; they are the conditions that inquire within a domain intelligible in the first place.

Because darśanas operate at this meta-methodological level, they do not require observation, experimentation, or historical accumulation for their own justification. To demand such evidence from a darśana is analogous to demanding laboratory data from logic or empirical trials from ethical theory. The absence of experimentation at this level is not a deficiency; it is a structural necessity.

A governing framework cannot be constituted by what it governs. Legal constitutions do not adjudicate cases, medical ethics does not prescribe drugs, and logic does not establish empirical facts. Their authority derives precisely from their independence from execution. Darśanas preserve this independence deliberately. Were they to be absorbed into empirical practice, they would lose the capacity to regulate scope, adjudicate conflicts, and prevent methodological overreach.

This structural separation also explains the long-standing coexistence of multiple darśanas within Indian intellectual life. They are not rival explanations of the same domain, competing for empirical supremacy. Rather, they represent distinct epistemic contracts governing different kinds of inquiry. Their plurality is not a symptom of fragmentation but a consequence of disciplined methodological restraint.

Seen in this light, the non-empirical character of darśanas is neither accidental nor archaic. It is the cornerstone of an epistemic architecture in which governance and execution are kept distinct—an architecture that makes room for rigorous empirical practice without collapsing all forms of knowledge into a single method.

Śāstras as the Site of Evidence and Experimentation

If darśanas govern inquiry, where does empirical knowledge arise?

Unambiguously: in the śāstras.

Ayurveda observes bodies, administers interventions, records outcomes, corrects procedures, and accumulates clinical experience. Architecture measures, constructs, fails, revises, and refines proportions. Agriculture adapts to climate, soil, and seasons through long-term observation. Astronomy records celestial motion across centuries. Metallurgy and rasāyana employ repeated trials, apparatus, and procedural refinement.

Observation, experimentation, correction, and historical accumulation are not marginal in Indian knowledge systems. They are central—but they appear where they belong: at the applied level. Śāstras answer empirical questions: What works? Under what conditions? With what reliability? These questions demand evidence.

Darśanas answer a different question altogether: What kind of inquiry is legitimate here at all?

Where Comparison with Modern Science Is Legitimate

A one-to-one comparison with modern science becomes meaningful only at the level of śāstras.

Medicine maps to Ayurveda. Architecture maps to śilpa and vāstu traditions. Astronomy maps to jyotiṣa. Agriculture, metallurgy, and pharmacology map cleanly to their modern counterparts. At this level, comparison is not only possible but necessary, and Indian śāstras withstand it without embarrassment.

Attempting the same mapping at the level of darśanas produces confusion. Darśanas do not correspond to physics, chemistry, or biology. They correspond to something modern science relies upon but has rarely categorised explicitly: meta-methodological governance.

Indian knowledge systems made this governance foundational. Modern science often leaves it implicit.

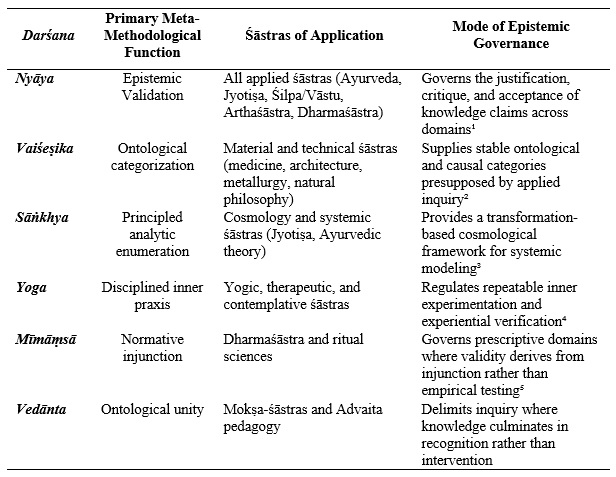

The table below summarises this relationship by distinguishing between darśanas as governing frameworks and śāstras as sites of execution.

(Table 1. Darśanas and the Śāstras They Epistemically Govern)

(Notes on Interpretation

This table articulates relations of epistemic governance, not claims of linear historical derivation or disciplinary “production.” Darśanas are presented as meta-methodological frameworks that govern the conditions of inquiry, while śāstras function as sites of execution where observation, experimentation, and correction occur. Indian intellectual traditions developed through shared metaphysical commitments and disciplined methodological separation, rather than through explicit institutional inheritance or causal lineage.)

Nyāya, Meta-Method, and the Limits of Modern Science

A frequent objection arises at this stage: if darśanas are domain-specific, why does Nyāya appear to function as a “backbone” of the system?

The answer requires care. Nyāya is not hierarchically superior to other darśanas, nor does it govern their substantive claims about reality. Its role is orthogonal. Nyāya formalizes the norms of public justification that any knowledge claim—regardless of domain—must satisfy to be intelligible, disputable, and decidable. These include the articulation of epistemic doubt (saṃśaya), the identification of error (doṣa), the regulation of inquiry process (vāda, jalpa, vitaṇḍā), and the point of epistemic halt (nigrahasthāna).

These are not domain theories. They do not tell us what exists, how the body functions, or how planets move. They govern how claims about such matters are to be examined, challenged, corrected, and accepted. Every applied śāstra and every darśana that advances public knowledge implicitly relies on such norms. Nyāya’s distinctive contribution lies in making them explicit.

In modern science, these functions unquestionably exist, but they are dispersed. Logic, statistics, experimental design, peer review, replication norms, and informal disciplinary practices together perform roles analogous to those articulated systematically within Nyāya. The difference is not one of presence but of articulation. Modern science operates with a powerful meta-method that largely remains implicit, reconstructed only retrospectively by philosophy of science.

This implicitness has consequences. Because methodological boundaries are not always clearly articulated, techniques developed for one domain are frequently universalized without sufficient justification. Methodological overreach—often labelled scientism—emerges when tools appropriate for empirical intervention are extended indiscriminately to domains that require different kinds of explanation, evidence, or closure.

Indian darśanas exist precisely to prevent such overreach. They insist, from the outset, that not all domains admit the same forms of inquiry. Methodological pluralism is therefore disciplined rather than anarchic. Nyāya functions as a “backbone” only in this limited but crucial sense: it maintains epistemic hygiene across domains without subsuming them, preserving plurality without collapsing it into relativism.

Conclusion:

Darśanas Frame Inquiry, Śāstras Execute Practice

The correct question, then, is not: Why didn’t darśanas experiment?

It is: Why has modern science never fully articulated its own meta-methodological layer?

Indian Knowledge Systems did not lack empirical rigor. They refused to confuse governance with execution. Darśanas regulated the conditions under which inquiry could meaningfully proceed; śāstras enacted inquiry through observation, experimentation, procedural refinement, and historical accumulation. Evidence appeared where it was required; restraint appeared where it was necessary.

Darśanas are therefore not parallel to modern sciences. They operate at a different logical level. They are explicit, domain-specific meta-methods that govern inquiry itself, while śāstras are the applied disciplines in which knowledge is generated, tested, and corrected. A one-to-one comparison with modern science is legitimate only at the level of śāstras.

Seen in this light, the much-asked question of “missing experiments” dissolves. What remains is a clearer appreciation of an intellectual architecture that separated governance from execution with remarkable discipline—and, in doing so, enabled empirical practice without scientism and pluralism without epistemic collapse.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, for his constant guidance and for helping me balance traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives. His support has been invaluable in shaping the direction and depth of this essay.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions, which significantly enhanced the clarity and philosophical precision of this work.

My daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), offered a thoughtful and meticulous editorial review of the article.

References:

- Garikapati Pavan Kumar. Indian Knowledge Systems as Epistemic Architectures: Transmission, Validation, and Ontology. Zenodo, 2025. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17970871

- Halbfass, Wilhelm. India and Europe: An Essay in Understanding. Albany: SUNY Press, 1988.

- Matilal, Bimal N. The Character of Logic in India. Albany: SUNY Press, 1998.

- Staal, Frits. Concepts of Science in Europe and Asia. Leiden: International Institute for Asian Studies, 1993.

Feature Image Credit: wikipedia.org

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.