We handle data and information, collect it, and process it – but none of this is jñāna. In Sanskrit thought, jñāna is illumination: the moment something becomes evident in awareness. Across cultures, knowledge is often treated as something stored or accumulated. Yet, the Indic view, shaped by Pāṇini’s linguistic precision and refined across the darśanas, offers a deeper understanding: what we commonly call “cognition” is not the mind processing data but awareness rendering an object clear. Read alongside contemporary studies of mind, this ancient insight reveals a model of knowing that is both subtle and strikingly relevant to modern inquiry.

Most cultures describe knowledge as something we possess -a stored fact, a belief kept in the mind’s inner cabinet. Modern psychology reinforces this picture by portraying the mind as a system that receives inputs, holds information, and delivers outputs.

Classical Indian thought, however – linguistic, philosophical, and yogic, presents a markedly different understanding. It sees knowing not as the accumulation of information but as a shift in awareness, a disclosure, an illumination.

The Sanskrit term for this illumination is jñāna. Commonly rendered as “knowledge,” it is in fact far more dynamic, and its meaning is embedded in the very structure of the language. When we consider Pāṇini, the six darśanas, and even contemporary studies of mind, a coherent picture emerges: knowing is layered, momentary, and transformative – an unfolding of awareness rather than the handling of information.

The Linguistic Root (√jñā): Knowledge as Illumination, Not Storage

Sanskrit stands apart among ancient languages for its highly structured grammatical tradition. Pāṇini’s generative system derives every noun and verb from a root (dhātu) that encodes the fundamental movement of knowing implied by the word.

The root √jñā (Dhātupāṭha 1507, krayādigaṇa: jñā – avabodhane) does not point to the storing of information. Its classical sense is to know by making the object evident, to bring it into illumination, to apprehend it with clarity. This becomes even sharper when contrasted with √budh – avagamane (Dhātupāṭha 1172, divādigaṇa). Avagamana refers to grasping or comprehending, whereas avabodhana denotes illumination, knowledge awakened into evident awareness. Thus, jñāna is not retention but revelation.

The semantic field of √jñā therefore marks a shift in awareness: what was previously obscure becomes intelligible. Linguistically and philosophically, the Indian tradition conceives knowledge not as a possession but as a disclosure, an event in which illumination arises in consciousness. This metaphor of illumination lies at the foundation of India’s sciences of knowing.

If jñāna is illumination rather than storage, then its preservation requires a medium that can reproduce the conditions for clarity, not merely hold symbols. This raises a deeper question: How is illumination to be carried, transmitted, and made available across generations?

Early civilizations turned to writing – Sumerian cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Shang oracle-bone script, ingenious systems for preserving information. Yet, for all their sophistication, scripts remain limited: they can record words, but not the inner processes that give rise to understanding.

In contrast, the oral architecture of ancient India, rooted in the apauruṣeya Vedas, unfolded as a self-correcting discipline. Through recitation, metre, accent, science of sound, and memorisation, it ensured a fidelity far exceeding what writing could guarantee. This architecture did not merely preserve content; it preserved the precision of knowing, enabling insights to travel across millennia without distortion. It embodied a distinctive view of knowledge: that the task is not to archive words but to recreate the conditions in which illumination can arise.

Thus, the human mind became the living cuneiform, a medium uniquely suited to carry jñāna across generations without loss of clarity.

A Layered Architecture of Knowing: Prajñāna → Vṛtti-jñāna → Vijñāna

Across the Vedic knowledge systems, a coherent and layered understanding of knowing emerges. The six darśanas, Nyāya, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṁsā, and Vedānta, are six distinct angles of a single Vedic inquiry. All accept the authority of the Veda and illuminate different dimensions of jīva, jagat, and Īśvara, ultimately pointing toward brahma-jñāna.

Within this shared universe of inquiry, jñāna unfolds in three progressively refined layers, each grounded in the root √jñā yet emphasizing a different mode of illumination.

- Prajñāna — the Primordial Luminosity of Awareness

Prajñāna refers to the innate luminosity of consciousness, the fundamental capacity to illuminate rather than store. The Veda and Upaniṣads describe this luminosity as svayam-prakāśa, self-revealing. The Aitareya Upaniṣad (3.3) declares prajñānam brahma, identifying this self-revealing awareness as the very nature of reality.

In the unified Vedic vision, prajñāna is the ever-present substratum assumed by all darśanas, the self-luminous ground of knowing that neither arises nor is attained but is uncovered when obscurations fall away. It is not an outcome of inquiry but the condition that makes inquiry possible: the luminosity by which perception becomes clear, inference gains meaning, and contemplative insight becomes possible.

The darśanas differ only in the disciplines they prescribe for removing the layers of avidyā, vṛtti-noise, or conceptual superimposition that veil this always-present disclosure. Thus, prajñāna is not the culmination of a path but the unchanging baseline from which all cognition proceeds and to which every mode of knowing ultimately returns once its distortions are cleared.

- Vṛtti-jñāna — Knowing Arising Through Momentary Mental Modifications

When awareness engages with objects, it does so through vṛttis, momentary configurations of the mind (citta). This is not unique to Yoga; the idea is woven throughout the darśanas:

- Nyāya’s account of valid knowing depends on the “rise” of a specific mental episode.

- Sāṃkhya’s buddhi-vṛttis function in the same structural manner.

- Vedānta accepts vṛtti-jñāna to explain how the mind reflects consciousness.

Thus vṛtti-jñāna is momentary knowing, a particular mode in which awareness takes the form of, and illuminates, a specific object.

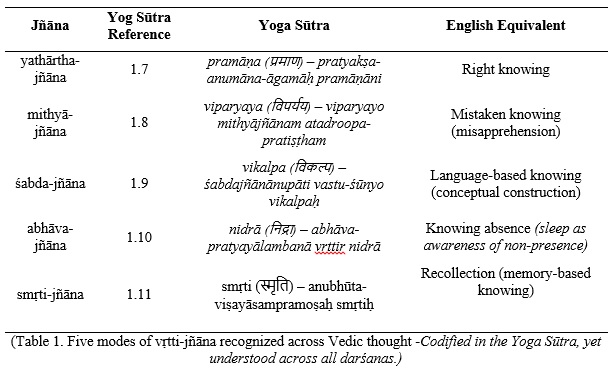

A traditional classification of these moments of knowing appears in Yoga Sūtra 1.6–1.11 (pramāṇa-viparyaya-vikalpa-nidrā-smṛtayaḥ), which identifies five fundamental patterns of vṛtti-based knowing.

(Table 1. Five modes of vṛtti-jñāna recognized across Vedic thought –Codified in the Yoga Sūtra, yet understood across all darśanas.)

These vṛttis are not independent psychological constructs; they are the modes through which prajñāna manifests when the mind has been refined by śravaṇa, manana, nididhyāsana, tapas, and disciplined inquiry. In this view, cognition is not a production of the mind but a temporary shaping of the ever-present luminosity of consciousness. Each vṛtti marks a momentary modification, a discrete configuration of awareness that enables a particular form of knowing. This episodic account of cognition, while articulated phenomenologically in the Yogic tradition, bears intriguing parallels to contemporary descriptions of neural state updates and transient representational patterns, though without reducing awareness to neural mechanics.

- Vijñāna — Structured, Discriminative Illumination

Vijñāna refers to knowing that has become articulated, structured, and discriminatively clear. The prefix vi- in vijñāna signals precision, correct delimitation, and clarified apprehension. It is the movement from the raw, momentary flash of a vṛtti to a stable, discriminative understanding (viveka-jñāna).

Whereas vṛtti-jñāna is episodic and transient, vijñāna is understanding that has settled into clarity, structured enough to guide action, reasoning, and further inquiry. It is the level at which awareness becomes organized: distinctions are recognised, relations are understood, and meaning is stabilised.

In this way, vijñāna is not a new entity or faculty but a refinement of illumination:

- the sifting of the valid from the erroneous,

- the stabilisation of a momentary flash into a coherent insight,

- the structuring of awareness into clear, discriminative patterns.

Thus, vijñāna corresponds to pure discriminative illumination (viveka-jñāna), the capacity to see things “as they are,” free from confusion, projection, or superimposition. At this stage knowing becomes reliable, steady, and aligned with truth, forming a bridge between the momentary movements of mind and the ever-present luminosity of prajñāna.

Ultimately, vijñāna fulfils its highest purpose by enabling the discrimination that reveals the inherent unity underlying jīva, jagat, and Īśvara, not by generating something new, but by clearing the obscuration that once veiled what was always present.

Six Darśanas, One Convergent Insight

When the six Vedic darśanas are read together, they reveal a single, integrated movement of knowing. Each darśana engages a distinct layer of jñāna and offers a pathway through which the seeker uncovers prajñānam, the self-luminous ground of awareness.

- Pūrva and Uttara Mīmāṃsā emphasise the cultivation of Brahma-vṛtti, enabling the unfolding of Brahma-jñāna.

- Yoga prescribes the stilling of vṛtti-jñāna so that the ever-present prajñānam shines without obstruction.

- Sāṅkhya and Vaiśeṣika refine vijñāna through clear discrimination and precise understanding of categories.

- Nyāya begins with yathārtha-jñāna and provides the disciplined methods that support all these pathways as they mature.

Across these six darśanas, a shared insight becomes unmistakable:

Knowledge is not something stored or possessed—it unfolds.

Cognition is not a container—it is an event of illumination.

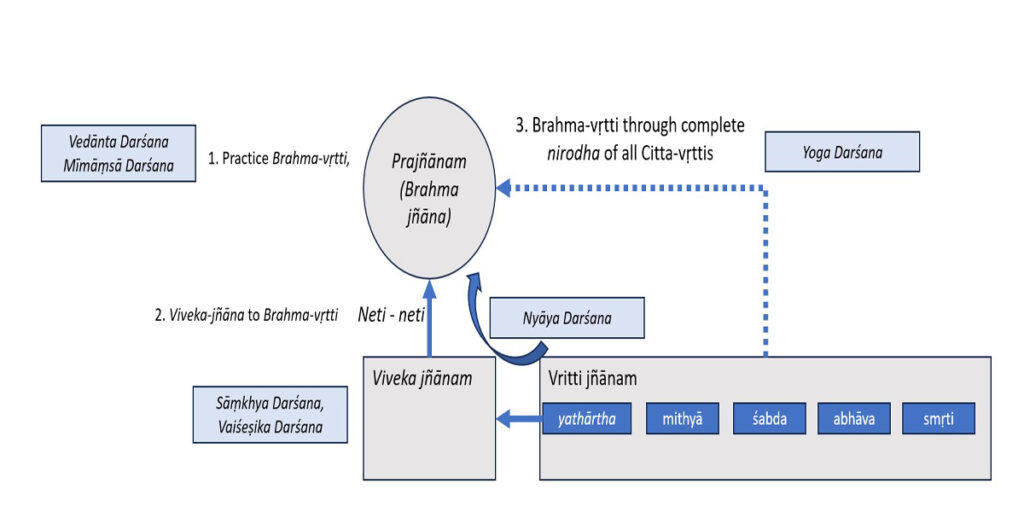

Figure 1 below illustrates how each darśana strengthens and complements the three-layer jñāna model.

(Figure. 1: Three pathways to attaining Brahma-vṛtti)

(Path 1: Direct practice of Brahma-vṛtti. Path 2: The “neti–neti” progression—citta-vṛtti → viveka-vṛtti → Brahma-vṛtti. Path 3: Complete nirodha of all citta-vṛttis.)

When viewed in the light of jñāna-traya and the distinction between para vidyā and apara vidyā, the six classical darśanas are complementary pathways of illumination. Each engages a different layer of knowing, refining the seeker’s faculties so that the revelation of prajñānam becomes possible.

Nyāya — Refinement of Yathārtha-jñāna

Nyāya begins with yathārtha-jñāna – right knowing – and refines it through the disciplined study of pramāṇa. By resolving saṃśaya (doubt) and removing doṣa (error), it ensures that pratyakṣa, anumāna, and śabda bring forth reliable knowing. In doing so, Nyāya purifies the instruments of knowledge, preparing the mind to apprehend tattva with clarity, steadiness, and discriminative precision.

Vaiśeṣika — Precision within Vijñāna

Vaiśeṣika sharpens vijñāna through its precise articulation of the padārthas – substance, quality, motion, universals, individuality, inherence, and related categories. This clear delineation trains the intellect to discern distinctions with consistency and exactness. By fortifying discriminative understanding, Vaiśeṣika stabilises the seeker’s insight and prepares the mind for deeper clarity.

Sāṅkhya — Deep Viveka through Vijñāna

Sāṅkhya presents a layered unfolding of the tattvas, culminating in the recognition of the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti. This is viveka in its most penetrating form: discerning consciousness as entirely distinct from all material activity. Though Sāṅkhya does not cross into Advaita’s non-dual vision, its discriminative clarity serves as a powerful preparation—steadying the mind for Vedānta’s revelation of prajñānam.

Yoga — Mastery of Vṛtti-jñāna

Patañjali defines Yoga as citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ – the stilling of the movements of mind. Through disciplined attention, ethical stability, and meditative absorption, Yoga calms and clarifies vṛtti-jñāna. When the mind becomes steady, transparent, and free of turbulence, the ever-present witnessing consciousness naturally reveals itself. Yoga therefore provides the inner stillness in which the illumination of prajñānam becomes unmistakable.

Mīmāṃsā — Purification of Adhikāra through Steady Vṛtti

Mīmāṃsā emphasises dharma, disciplined action, and inner responsibility. By cultivating steadiness in conduct and purity of intention, it refines the seeker’s adhikāra, the preparedness to receive higher knowledge. Through the discipline of right action, Mīmāṃsā stabilises vṛtti-jñāna, preparing the mind for contemplation and making it fit for the revelation of prajñānam.

Vedānta — Direct Realisation of Prajñānam

Vedānta operates at the level of prajñānam itself. Through śravaṇa, manana, and nididhyāsana, it unveils the identity of Brahman. The mahāvākyas—tat tvam asi, ayaṃ ātmā brahma, prajñānam brahma—do not introduce anything new; they remove the obscuration that veils what is ever-present. Vedānta completes the movement of knowing by revealing the self-luminous awareness that underlies all experience.

A Convergent Continuum

Taken together, the six darśanas form a seamless continuum of knowing:

- Nyāya, Yoga, and Mīmāṃsā refine vṛtti-jñāna—steadying, clarifying, and purifying the movements of mind.

- Vaiśeṣika and Sāṅkhya sharpen vijñāna—bringing precision, discrimination, and clear understanding.

- Vedānta unveils prajñānam—the self-luminous ground that underlies all knowing.

None is subordinate; none is redundant. Each tradition addresses a different layer of the seeker’s inner movement—from initial perception, through discriminative clarity, to unbroken illumination. Their diversity creates a completeness in which every temperament, discipline, and disposition finds an entryway into the same truth.

Thus, the human mind became the living cuneiform—engraving, refining, and finally dissolving its own inscriptions until only pure illumination remains.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, for his constant guidance and for helping me balance traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives. His support has been invaluable in shaping the direction and depth of this essay.

I would like to thank Śrī Vyākaraṇa Vidyāpraveena Kandala Venkata Rama Tirumalacharyulu, former Sanskrit Lecturer at Lal Bahadur Shastri Oriental College, Chinanindrakolanu, West Godavari, and S.N.S. College, Chittiguduru, Krishna, for guiding me in the Dhātupāṭha and Pāṇini’s grammar needed for this essay.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions, which significantly enhanced the clarity and philosophical precision of this work.

My daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), offered a thoughtful and meticulous editorial review of the article.

References:

Garikapati, Pavan Kumar. 2025. “The Oral Architecture of the Vedāṅgas: Preserving the Eternal Veda.” Indica Today, November 27, 2025. https://www.indica.today/long-reads/the-oral-architecture-of-the-veda%E1%B9%85gas-preserving-the-eternal-veda/.

Gambhirananda, Swami, trans. 1985. The Upanishads. Vol. 1. Chennai: Ramakrishna Math.

———. 1985. The Upanishads. Vol. 2. Chennai: Ramakrishna Math.

Pāṇini. 1969. The Dhātupāṭha of Pāṇini with the Dhatvartha Prakāśikā Notes. Edited by Pt. Kanaklal Sarma. https://archive.org/details/the-dhatupatha-of-panini/page/n9/mode/2up.

Radhakrishnan, S. 1923. Indian Philosophy. Vol. 1: Theistic Schools. London: Oxford University Press.

———. 1927. Indian Philosophy. Vol. 2: Non-Theistic and Vedānta Schools. London: Oxford University Press.

Telugu Akademi. 2017. Pāṇinīya Aṣṭādhyāyī: Kāśikāvṛtti Sahitam (Prathama, Dvitīya Bhāgamulu). Translated into Telugu by Prof. Ravva Sri Hari. 2 vols. Hyderabad: Telugu Akademi. Reprint.

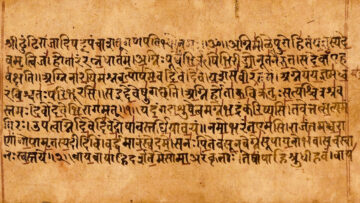

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.