I. Introduction

From the beginning of human inquiry, people have asked: How did the universe begin? What preceded existence? What sustains it, and where does it ultimately go? The Bhāratīya ṛṣis approached these questions not through faith or speculation but through careful observation, reasoning, and revealed knowledge—pramāṇas that integrate experience, reflection, and Vedic insight.

Among the many streams of thought, Sāṅkhya Darśana stands out as one of the earliest systematic explorations of the cosmos. It provides a structured understanding of how the unmanifest potential (avyakta) unfolds into the manifest universe. Sāṅkhya explains not only the emergence of matter and mind but also the subtler principles that underlie perception, action, and consciousness.

This inquiry is not mythology; it is a science of existence, offering precise principles for understanding the unfolding of the universe. Its approach anticipates, in its own domain, the logical rigor of inquiry and explanation that modern studies seek.

II. Foundations of Sāṅkhya

Sāṅkhya is one of the six classical ṣaḍ-darśanas and investigates the principles of creation, transformation, and conscious experience. While Sage Kapila is revered as its codifier, the roots of Sāṅkhya extend to the Vedas, with ideas refined across centuries of reflection and teaching.

Continuum of Sources

Sāṅkhya’s principles are revealed across a wide textual spectrum—from the Ṛgveda (e.g., Nāṣadīya Sūkta, Puruṣa Sūkta) and Atharva Veda (Prāṇa Sūkta), to the Brāhmaṇas (Śatapatha, Aitareya), Āraṇyakas, and Upaniṣads (Śvetāśvatara, Praśna, Maitrī). Later Purāṇic texts and the Itihāsas further elaborate on tattvas, guṇas, and cosmic hierarchies, demonstrating a continuity across traditions.

Five Fundamental Principles

The coherence of Sāṅkhya rests on five interlinked premises, which provide the foundation for its view of knowledge and cosmos:

- Śruti-pramāṇa: The Vedas are accepted as the revealed foundation, integrated with direct experience and reasoning.

- Layered Causality: Creation unfolds from subtle potential to gross manifestation, forming a structured and ordered cosmos.

- Cross-Traditional Continuity: Sāṅkhya harmonizes Vedic, Purāṇic, and darśana traditions, preserving a continuity of inquiry.

- Comprehensive Framework of Tattvas: The twenty-five tattvas include material, mind, and conscious domains, providing a unified account of reality.

- Living Inquiry: Sāṅkhya is not static; it continues to guide reflection on consciousness, mind, and the principles of change in the universe.

Methodological Note:

This study approaches Sāṅkhya as a dynamic inquiry into the principles of creation and transformation. Rather than a fixed doctrine, it reflects a coherent account of the universe as experienced, observed, and contemplated across traditions.

III. Philosophical Foundation – Satkāryavāda

Satkāryavāda, a central principle of Sāṅkhya, holds that the effect (kārya) already exists within its cause (kāraṇa). Nothing arises from nothing; creation is not arbitrary but a transformation of what is latent. Just as a tree exists potentially within a seed, a pot within clay, or butter within milk, the universe unfolds from the unmanifest (avyakta) into the manifest (vyakta) through natural and necessary evolution. In every case, the effect is inherent in the cause, awaiting the right conditions for expression.

This doctrine is not only established through yukti (reasoning) but also recognizes anubhava (direct experience) and Veda pramāṇa (śruti) as valid sources of knowledge. Sāṅkhya teaches that revealed wisdom guides understanding of realities beyond immediate perception, while reasoning and experience confirm the unfolding of the universe. In this way, Satkāryavāda harmonizes yukti, anubhava, and śruti, demonstrating that the cosmos evolves in a lawful and intelligible manner from latent potential to manifest reality.

Īśvarakṛṣṇa lays out five logical reasons for Satkāryavāda in the Sāṅkhya Kārikā 9:

असदकरणादुपादानग्रहणात् सर्वसम्भवाभावात् ।

शक्तस्य शक्यकरणात् कारणभावाच्च सत्कार्यम् ॥ ९ ॥

asadakaraṇāt upādānagrahaṇāt sarvasambhavābhāvāt ।

śaktasya śakyakaraṇāt kāraṇabhāvācca satkāryam ॥ 9 ॥

He gives five reasons why the effect must pre-exist in the cause:

- The non-existent cannot produce the existent (asadakaraṇāt). From nothing, nothing comes.

- Every effect requires a material cause (upādānagrahaṇāt). A pot arises from clay, not from stone or cloth.

- Not everything arises from everything (sarvasambhavābhāvāt). A mango seed yields a mango tree, not a neem.

- An effect emerges only from a cause with the potential to produce it (śaktasya śakyakaraṇāt). Milk can yield curd, but not oil.

- The cause persists as the substance of the effect (kāraṇabhāvāt). Clay remains present in the pot—it has only changed form.

Through these arguments, Sāṅkhya grounds cosmic evolution in necessity and continuity. Thus, the universe is not a whimsical creation ex nihilo, but a systematic unfolding of the unmanifest (avyakta) into the manifest

IV. The Structured Evolutionary Framework of Sāṅkhya

Sāṅkhya Darśana presents one of the most systematic and precisely structured frameworks in humanity’s exploration of cosmic origins. Unlike speculative metaphysics, Sāṅkhya builds its model of creation on first principles, pramāṇa-based reasoning, and causality. It explains the evolution of the universe through a hierarchy of 25 tattvas (principles), integrating matter, mind, and consciousness into a single vision.

a. Avyakta: The Unmanifest Potential

The Ṛgveda’s Nāṣadīya Sūkta (10.129) reveals a striking vision of pre-existence:

नासदासीन्नो सदासीत्तदानीं

नासीद्रजो नो व्योमा परो यत् ॥

“nā́sad āsīn no sád āsīt tadānīṃ,

nā́sīd rajo no vyomā paro yat…”

“There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

there was neither realm of space, nor the sky beyond.”

This utterance points to a reality prior to manifestation, where being and non-being were indistinguishable—a unified, undifferentiated potential. Sāṅkhya identifies this pre-creation state as Avyakta or mūla-prakṛti: the unmanifest, eternal substratum from which all manifest realities arise when in proximity to puruṣa, the conscious principle.

The Yoga tradition echoes this insight. Yoga Sūtra 2.19 describes the stages of prakṛti as: “viśeṣāviśeṣa-liṅgamātrāliṅgāni guṇaparvāṇi” — the manifest (dṛśya), shaped by the three guṇas, unfolds through progressive levels. In this sequence, the unmanifest (Avyakta) corresponds to the final and most subtle stage: Aliṅga—where the guṇas remain in perfect equilibrium, neither manifesting nor disturbing one another. It is this undisturbed balance that Sāṅkhya identifies as the latent ground of creation, awaiting the catalytic presence of puruṣa to initiate evolution.

The three guṇas—sattva (illumination), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia)—are described in their natural tendencies. In the state of Avyakta, these guṇas exist in perfect equilibrium, neither manifesting nor disturbing each other. Creation begins only when this balance is perturbed.

Īśvarakṛṣṇa’s Sāṅkhya Kārikā 10 offers a detailed characterization of vyaktam—the manifest world—as a product (hetu), impermanent (anityam), non-pervasive (avyāpi), active (sakriyam), multiform (anekam), dependent (āśritam), marked by signs (liṅgam), composed of parts (sāvayavam), and subordinate (paratantram). In contrast, the avyakta—the unmanifest—is defined by the reversal of these attributes. It is eternal, pervasive, inactive, undifferentiated, independent, unmarked, partless, and autonomous—the subtle substratum underlying all manifested phenomena.

Though pregnant with infinite potential, prakṛti remains in a state of equilibrium and unmanifest, holding the seed of creation until the disturbance of the guṇas—triggered by the mere proximity of puruṣa—initiates evolution.

Kārikā 11 further elaborates prakṛti as triguṇam—constituted by sattva (illumination), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia). It is acetana (unintelligent), sāmānya (general), and prasavadharma—possessing the inherent tendency to evolve. The opposite of this is puruṣa: conscious, specific, and non-evolving.

This unmanifest potential—avyaktaṁ tathā pradhānaṁ—becomes the source from which the cosmos emerges, once the equilibrium of the guṇas is disturbed. In Sāṅkhya, creation is not a spontaneous act but a lawful unfolding from latent potential into manifest reality, governed by the inherent nature of prakṛti and catalyzed by the presence of puruṣa.

Śaṅkara, in his Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya (1.4.3), affirms that the prior state of the world—avyakta (prāg-avasthā jagataḥ)—must be accepted (sā cāvaśyābhyupagantavyā). Without acknowledging this, the very notion of creation loses meaning (arthavatī hi sā). Yet, this avyakta is not independent; it exists under the control of Īśvara (parameśvarādhīnatva). The acceptance of such a dependent avyakta is precisely what secures Īśvara’s role as sraṣṭṛ (Creator). As Śaṅkara states: na hi tayā vinā parameśvarasya sraṣṭṛtvaṃ sidhyati — “for without it, the creatorship of the Īśvara’s cannot be established.” He concludes with the principle: śaktirahitasya pravṛttyanupatteḥ — “without power, no activity is possible.” Thus, avyakta is not an autonomous principle but rather the very śakti (power) of Brahman/Īśvara.

b. Emergence of the Sapta Vikṛtis

The Ṛgveda (10.121) describes the first stirrings of creation with the arising of Hiraṇyagarbha, the golden germ:

हिरण्यगर्भः समवर्तताग्रे भूतस्य जातः पतिरेक आसीत्

“hiraṇyagarbhaḥ samavartatāgre bhūtasya jātāḥ patir eka āsīt” (Ṛgveda 10.121.1) “Hiraṇyagarbha arose in the beginning; he alone was associated with all that has come into being.”

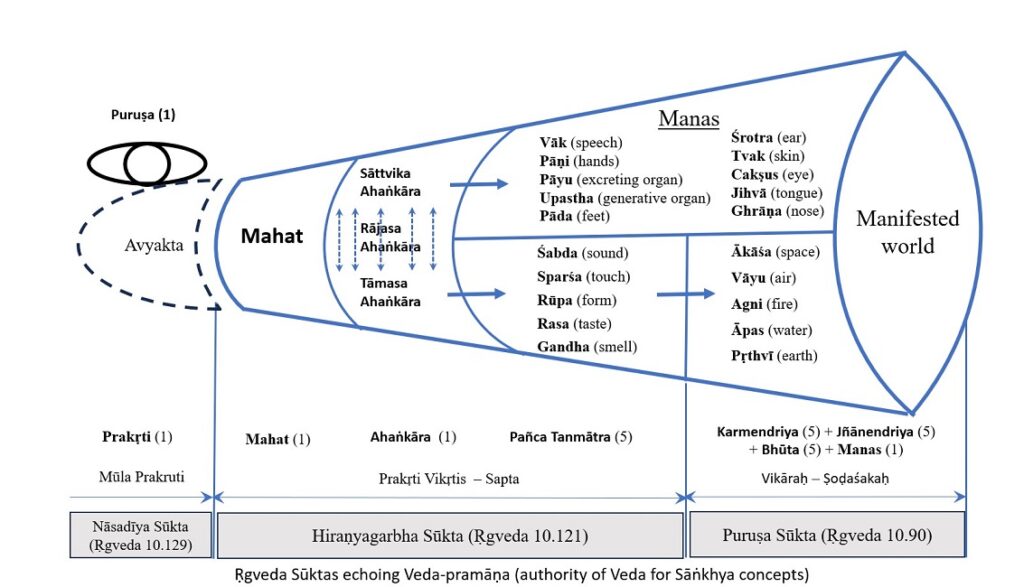

This Vedic image corresponds to the first evolute in Sāṅkhya: the transition from unmanifest potential (avyakta) to manifest creation. Sāṅkhya Kārikā 22–25 codifies this emergence through seven foundational principles, collectively known as the Sapta Prakṛtivikṛtis.

The process begins with Mahat (Cosmic Intelligence / Buddhi), The first expression of order. Its essential function is decisive knowledge (adhyavasāya). When sattva predominates, Mahat manifests clarity (jñāna), detachment (virāga), and mastery (aiśvarya); when tamas dominates, it obscures with ignorance (ajñāna), attachment (rāga), and impotence (anaiśvarya).

From Mahat arises Ahaṃkāra, the principle of individuation, which introduces the sense of “I” and initiates differentiation within the evolving cosmos. This Ahaṃkāra unfolds along two generative streams. When sattva predominates, Sāttvika Ahaṃkāra gives rise to the eleven indriyas: five organs of perception (jñānendriyas), five organs of action (karmendriyas), and manas, the coordinating mind. When tamas prevails, Tāmasa Ahaṃkāra produces the five tanmātras—the subtle essences of sound, touch, form, taste, and smell that underlie all perceptible phenomena. The rājasa aspect of Ahaṃkāra does not generate new tattvas, but serves as the dynamic force that energizes and connects both the sāttvika and tāmasa streams, enabling their evolution.

These seven principles—sapta prakṛtivikṛtis—form the subtle scaffolding upon which the manifest universe is built.

In the Yoga framework, this stage corresponds to Liṅga-mātra and Aviśeṣa, as described in Yoga Sūtra 2.19. Liṅga-mātra refers to the “sign-only” level, where Mahat emerges as the first discernible principle of cosmic intelligence—marking the transition from undifferentiated potential to structured subtlety. Aviśeṣa denotes the subtler, less differentiated entities that follow: Ahaṅkāra and the five tanmātras. These principles, though not yet fully particularized, form the foundational scaffolding for the manifest cosmos.

c. Manifestation of the Ṣoḍaśakaḥ

The Ṛgveda’s Puruṣa Sūkta describes the emergence of Virāṭ Puruṣa, the universe as a conscious whole. This moment signifies a transition—from undifferentiated awareness to structured multiplicity. In this vision, yajña is the primordial act of integration (saṅgatikaraṇa), reverence (devapūjā), and offering (dāna). It is through this harmonization with ṛta, the cosmic rhythm, that the manifold universe unfolds. This intrinsic alignment initiates the differentiation of reality, giving rise to the various domains of existence.

तस्माद्विराळजायत विराजो अधि पूरुषः। स जातो अत्यरिच्यत पश्चाद्भूमिमथो पुरः॥५॥

tasmād virāḷajāyata virājo adhi pūruṣaḥ। sa jāto atyaricyata paścād bhūmim atho puraḥ॥5॥ (Ṛgveda 10.90.5)

“From Him was born Virāt, and from Virāt came forth the Puruṣa.

Born, He spread out on every side, behind and before the earth.”

This imagery of the one differentiating into the many resonates with Sāṅkhya’s account of the unfolding of the Ṣoḍaśa Tattvas. From Ahaṃkāra, evolution divides into two guṇa-based streams. Sāṅkhya Kārikā 26–28 describes:

Sāttvika Ahaṃkāra (Vaikr̥ta) gives rise to one coordinating Manas and the ten sensory organs (indriyas): five organs of perception (jñānendriyas) and five organs of action (karmendriyas). Manas integrates sensory input and orchestrates cognition, as it is of the nature of both sensory and motor organs (ubhayātmakam).

The five tanmātras generated by Tāmasa Ahaṃkāra evolve into the five mahābhūtas, or gross elements: space (ākāśa), air (vāyu), fire (tejas), water (āpa), and earth (pṛthivī).

Rājasa Ahaṃkāra (Taijasa) serves as the energetic driver, animating the Sāttvika and Tāmasa streams, catalyzing activity and transformation without directly producing new tattvas.

This stage corresponds to Viśeṣa in the Yoga Sūtra’s. Viśeṣa (Particulars) are the fully differentiated entities—five karmendriyas, five jñānendriyas, five mahābhūtas, and manas.

The sequence illustrates Sāṅkhya’s systematic logic: subtle, unobservable principles give rise to perceivable phenomena in a predictable and coherent manner. The Ṣoḍaśa Tattvas thus provide a structured map of the universe, showing how consciousness-adjacent principles gradually manifest as both mind, matter and energy, forming the complete lattice of existence.

A diagrammatic representation (see Figure 1.0) can summarize these relationships:

(Figure 1: Sankhya Cosmological Evolution: Prakṛti, disturbed by the guṇas in the presence of Puruṣa, evolves step by step into the manifest world of 24 tattvas.)

V. Modern Science: A Reflective Parallel

Modern science and Sāṅkhya offer distinct approaches to understanding reality. Science observes what is externally measurable—matter, energy, and physical processes. Bhāratīya śāstra, by contrast, explores what is directly experienced—consciousness, mind, and the subtle principles that shape manifestation. These are not opposing views, but complementary lenses. Each operates within its own domain and serves a different purpose.

Interestingly, modern cosmology arrives at a similar notion after millennia: the pre–Big Bang singularity, a state in which spacetime and matter-energy are compressed into an unmanifest potential. Yet Sāṅkhya’s avyakta is not a void or mathematical abstraction. It is a living matrix of the three guṇas, held in equilibrium and poised at the threshold of manifestation. Creation begins only when the proximity of puruṣa disturbs this balance—reminiscent of the “observer effect” in quantum physics, where the act of observation precipitates a change of state. Unlike physics, however, Sāṅkhya does not treat this potential as merely physical. It is a dynamic balance of guṇas in relation to consciousness.

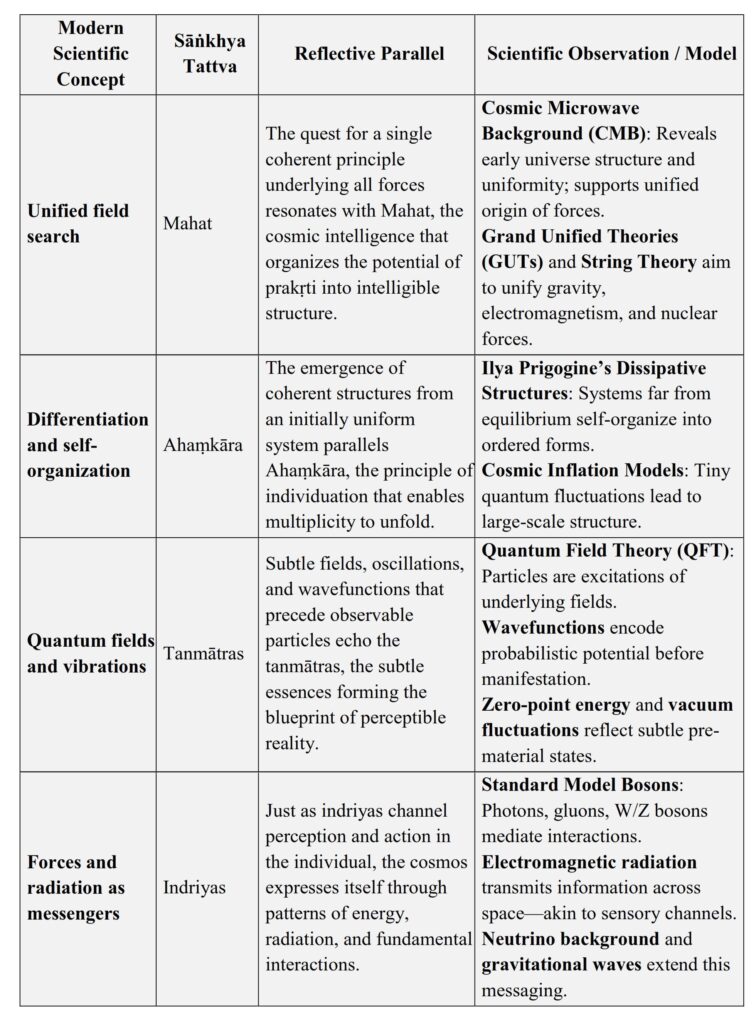

When viewed reflectively, certain resonances between these systems become visible. Though their foundations differ, both recognize patterns of emergence and transformation. The following table illustrates a few parallels:

Table 1: Reflective Parallels Between Modern Science and Sāṅkhya

Notes:

- CMB as Mahat: The Cosmic Microwave Background is not just residual radiation—it’s a snapshot of the universe’s earliest organizing intelligence, showing temperature fluctuations that seeded galaxies. This mirrors Mahat as the first structured principle emerging from prakṛti.

- Scientific models reflect the progression from subtle to gross, just as Sāṅkhya traces from tanmātras to mahābhūtas.

- These parallels are reflective, not literal. They show that ancient insights into manifestation and order continue to echo in modern inquiry.

Despite these parallels, a fundamental distinction remains. Sāṅkhya begins with puruṣa—consciousness—as the first principle. All manifestation unfolds in relation to this conscious presence. Science, on the other hand, begins with matter and energy. It studies what can be measured, but does not yet account for consciousness as the ground of reality. Sāṅkhya includes both what is seen and what is felt. It traces the journey from subtle to gross, from inner awareness to outer form. Science reveals many aspects of order, but its instruments are tuned to the external. Bhāratīya Śāstra explores both the manifest and the felt dimensions of existence.

VI. Closing Reflections

Sāṅkhya Darśana stands as a science of existence, offering a precise account of how the unmanifest potential (avyakta) unfolds into the manifest cosmos. It explains the cascade from subtle principles—Mahat, Ahaṃkāra, and Tanmātras—to the perceivable world of mind, senses, and matter.

This tradition preserves continuity across Veda, Upaniṣad, Darśana, and Purāṇa, making it one of the most systematic and coherent accounts of creation in human thought. Its framework integrates both subtle and gross dimensions, providing a layered understanding of the universe that is ordered, experiential, and deeply reflective.

Modern science, while limited to what can be measured and observed, occasionally mirrors aspects of this structure—patterns of coherence, differentiation, and the progression from subtle to gross. These parallels, however, are reflective, not equivalent.

The essential distinction remains clear. Science seeks laws that govern matter and energy. Bhāratīya śāstra begins with consciousness as the source—from which intelligence, matter, and all manifestations arise. Sāṅkhya reminds us that the cosmos is not only an external spectacle, but also a felt reality. Consciousness is not an emergent property—it is the foundation of all existence.

References

- Vedic Heritage. (n.d.). Rigveda – Shakala Saṃhitā – Mandala 10, Sūkta 129 [Śākala Saṃhitā text]. Vedic Heritage Portal. https://vedicheritage.gov.in/samhitas/rigveda/shakala-samhita/rigveda-shakala-samhita-mandal-10-sukta-129/

- Maharshi Patañjali. (n.d.). Pātañjalayogaśāstra. In Patañjalayogadarśana along with Vyāsabhāṣyam: Sūtrārtham–Sūtra Vyākhyānam–Sūtra Vipula Vyākhyānam, Bhāṣyārtham–Bhāṣya Vyākhyānam (A. Parishuddananda Giri Swamy, Ed.). Sri Vishwanatha Kshetram–Sri Parāśara Āśramam.

- Maharshi Vyāsa. (n.d.); Ādi Śaṅkara. (n.d.). Śrīmad Bhagavad Gītā: Telugu – Śaṅkarācārya Bhāṣya. Translated by Pullela, R. (2019). [Digital version]. Internet Archive.https://archive.org/details/srimadbhagavadgita-telugu-shankaracharyabhashya-translatedbyshripulleysramachandra

Note: The original text is available in Sanskrit rendered in Telugu script, preserving both linguistic fidelity and regional scriptural tradition.

- Ādi Śaṅkara. (n.d.). Brahmasūtra Śaṅkara Bhāṣyamu (M. V. Subrahmanya Śāstri, Ed.). Tenāli: Sādhana Grantha Maṇḍali.Śaṅkara. (2020). Brahmasūtra Śaṅkara Bhāṣyamu (M. V. Subrahmanya Śāstri, Ed.). Tenāli: Sādhana Grantha Maṇḍali.

- Īśvarakṛṣṇa. (n.d.). Sāṅkhya Kārikā: With the Tattva Kaumudī of Śrī Vācaspati Miśra (Swami Virupakshananda, Trans.). Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math.

- Ādi Śaṅkara’s Commentary on the Brahma Sūtras (Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya)

– Foundational Advaita Vedānta interpretation; articulates non-duality and the limits of conceptual knowledge. - Greene, B. (2004). The fabric of the cosmos: Space, time, and the texture of reality. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Hawking, S. (1988). A brief history of time: From the Big Bang to black holes. New York, NY: Bantam Books. — Explores cosmological origin, expansion, and dissolution.

- Yakubu, M. (2016). The fundamental problems of the unified field theory. IOSR Journal of Applied Physics, 8(3), 50–53. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jap/papers/Vol8-issue3/Version-1/I0803015053.pdf — Covers challenges in unifying quantum mechanics and general relativity; discusses string theory and early universe models relevant to Mahat and avyakta.

- Vizgin, V. P. (2021). Missed opportunities in the fundamental physics of the 20th century. Metaphysics, 2, 105–124. https://doi.org/10.22363/2224-7580-2021-2-105-124 — Explores the evolution of gauge field theory, quantum field theory, and the Standard Model; relevant to Tanmātras and Indriyas.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, for his constant guidance and for helping me balance traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives. His support has been invaluable in shaping the direction and depth of this essay.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions, which greatly enhanced the clarity and philosophical precision of the work.

My daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), offered subtle yet meaningful insights that shaped the clarity of the cosmological figure. Her presence in this work is felt more than spoken.

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.