Introduction

The meeting of Rāma and Bharata at Citrakūṭa, narrated in the Ayodhyākāṇḍa of Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa, is far more than a fraternal reunion—it is a profound exposition of rājadharma. Set against political upheaval and moral crisis, the episode transforms private grief into public instruction. Bharata, innocent of Kaikeyī’s conspiracy, returns to a fatherless kingdom and a fractured populace. His anguish is not only filial but civic: he witnesses the disruption of moral order and the erosion of his own legitimacy.

The encounter becomes a moral testing ground. Bharata rejects a throne tainted by deceit; Rāma reaffirms his commitment to satya and pitṛ-vākya-paripālanam by refusing to return prematurely. Yet the dialogue transcends personal virtue—it becomes a meditation on kingship. In Sarga 100, through seventy-seven ślokas, Rāma frames his inquiry as kuśala praśna—questions of well-being that double as a curriculum of statecraft.

These praśnas span personal discipline, ministerial appointments, judicial fairness, strategic intelligence, economic oversight, and the pursuit of higher ideals. They articulate a dharmic architecture of governance—ethical, consultative, and citizen-oriented. Far from being a prince in exile, Rāma treats the forest as an alternative rājya, a symbolic polity where dharma must be upheld even without a throne or court. Leadership, in this model, is portable and situational—anchored not in privilege but in responsibility.

Drawing directly from the original Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa (Gītā Press Telugu script), this essay highlights select verses that illuminate Rāma’s model of statesmanship—rooted in moral authority, the harmonization of duty and affection, and governance as universal responsibility. It situates the Citrakūṭa dialogue within the broader Indic discourse on political ethics, asking: How does Rāma articulate rājadharma through his dialogue with Bharata, and what lessons can be drawn for statecraft and democratic governance today?

The Citrakūṭa Encounter: Familial Meeting as Political Discourse

The meeting of Rāma and Bharata at Citrakūṭa is among the most emotionally charged and politically consequential episodes in the Rāmāyaṇa. Upon learning of the injustice behind Rāma’s vanavāsa and his own installation as heir, Bharata journeys to the forest—not to claim power, but to renounce it. Accompanied by ministers, citizens, and elders, he approaches Rāma in anguish, pleading for his return to Ayodhyā. His grief is tenderly portrayed: he prostrates before Rāma, denounces his mother’s actions, and begs forgiveness—embodying loyalty to both family and dharma.

For Rāma, too, the encounter is deeply fraternal. He embraces Bharata with compassion, consoles him, and acknowledges his sincerity. Yet beneath this affection, the exchange gradually shifts into a discourse on kingship. Rāma insists that Daśaratha’s word must be honoured, regardless of personal cost, and that Bharata, though reluctant, must bear the burden of governance. Here, love between brothers becomes the medium through which questions of political order, legitimacy, and ethical responsibility are explored.

The encounter thus operates on two intertwined registers. On the surface, it is a reconciliation of brothers sundered by fate; at a deeper level, it is a teaching moment in which Rāma articulates the principles of rājadharma. Through affectionate counsel—not royal command—he transforms a family dialogue into a lesson in statecraft. This pedagogic turn aligns with the Indic tradition of saṃvāda-based instruction, where philosophical and political truths are transmitted through emotionally resonant conversation rather than abstract treatise.

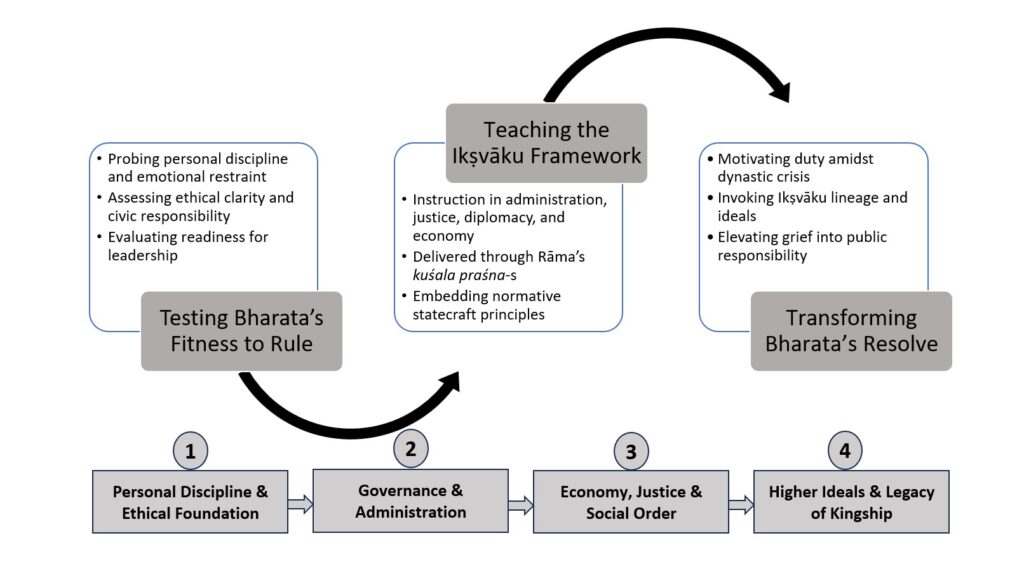

This episode also anticipates the triadic function of Rāma’s kuśala praśnas in Sarga 100: testing Bharata’s moral and administrative fitness, transmitting the Ikṣvāku blueprint of governance, and motivating him to uphold duty amidst dynastic crisis. These functions emerge organically from fraternal intimacy, demonstrating that political instruction in the epic is inseparable from emotional and ethical grounding.

In this light, Citrakūṭa is not merely a site of reunion—it is the locus where dharma assumes political form. The shift from grief to guidance, from kinship to kingship, sets the stage for Rāma’s methodical inquiries in Sarga 100.

Kuśala Praśna as Method of Instruction

In the Indic tradition, kuśala praśna—asking “well-being” questions—was never mere etiquette. Rooted in Vedic and epic ethos, such inquiries served as diagnostic tools to assess the moral, social, and political health of individuals and states. In the Rāmāyaṇa, Rāma uses this form, not for casual conversation with Bharata, but as a structured method of instruction. Framed in the register of fraternal concern, his questions unfold into a comprehensive checklist of governance. What begins as “Is all well?” expands into a survey of ethics, administration, and cosmic order.

The seventy-seven ślokas of Ayodhyākāṇḍa Sarga 100 reveal a striking pedagogical structure. Each query, though posed as concern for Bharata and Ayodhyā, functions as a directive—teaching what must be safeguarded for rulership to remain aligned with dharma. Rāma teaches by questioning, guiding Bharata to internalize principles of statecraft.

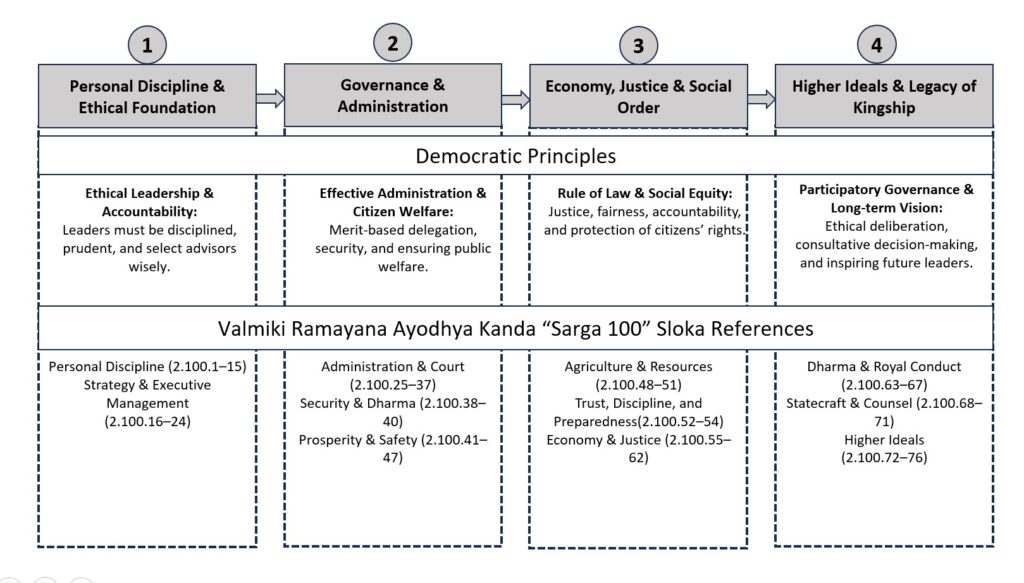

Grouped thematically, these praśnas form a systematic curriculum of kingship, revealing four timeless pillars of statesmanship—each resonating with modern democratic principles of leadership, administration, justice, and vision.

Pillar I: Personal Discipline & Ethical Foundation

Democratic Parallel: Ethical Leadership & Accountability

Rāma’s instruction begins not with the machinery of governance, but with the sovereign’s inner architecture. In Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.1–15, he emphasizes that kingship begins with self-mastery—restraint, prudence, and ethical clarity form the bedrock of rājadharma. A ruler must govern his senses before he governs a state; rashness, indulgence, or moral ambiguity disqualify leadership in the dharmic paradigm.

This ethic deepens in verses 2.100.16–24, where Rāma outlines executive strategy through a sequence of kuśala praśnas. His counsel is precise and layered:

- śūrāḥ śrutavanto jitendriyāḥ mantriṇaḥ — Appoint brave, learned, self-controlled ministers (2.100.16).

- mantraḥ vijayamūlaṁ hi susaṁvṛtaḥ — Well-guarded counsel is the root of victory (2.100.17).

- kāle’vabudhyase cintayasi arthanaipuṇam — Wakeful planning ensures judicious action (2.100.18).

- naikaḥ mantrayase na bahubhiḥ saha — Decide wisely, share cautiously (2.100.19).

- laghumūlaṁ mahodayam kṣipramārabhase kartum — Act promptly on high-yield endeavors (2.100.20)

- Conceal future plans, reveal only completed deeds, and prefer one wise advisor over a thousand fools (2.100.21–23)

Though framed as fraternal concern, these verses form a curriculum of ethical leadership. Rāma teaches that discretion, timing, and moral clarity are not optional—they are prerequisites for governance. The ruler’s character becomes the axis around which the state revolves.

Pillar II: Governance & Administration

Democratic Parallel: Effective Administration & Citizen Welfare

Once the sovereign’s ethical foundation is secured, Rāma’s discourse turns outward—to the architecture of governance. Ślokas 2.100.25–37 form a compact treatise on administrative discipline, merit-based appointments, and the moral scaffolding of statecraft. Here, kingship is not about dominion but about dharmic stewardship—where power is exercised to uphold collective welfare, not personal grandeur.

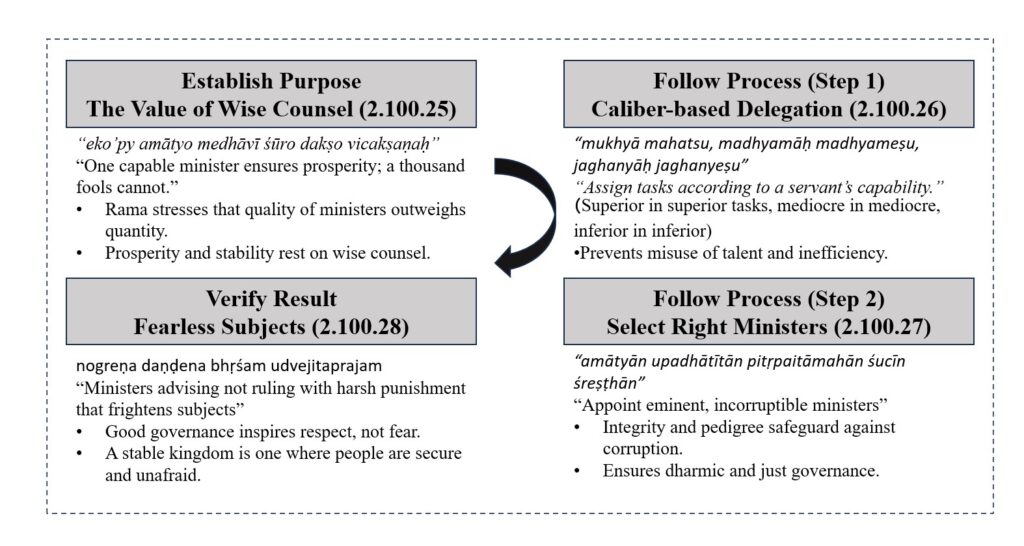

Rāma’s kuśala praśnas outline a four-step framework for effective governance:

- Establish Purpose – One wise minister ensures prosperity; a thousand fools cannot. (2.100.25)

- Follow Process (Step 1) – Delegate tasks based on capability. (2.100.26)

- Verify Result – Ministers must advise fearlessly, not rule harshly. (2.100.27)

- Follow Process (Step 2) – Appoint eminent, incorruptible ministers. (2.100.28)

(Figure 1: Rāma’s Four-Step Framework for Statecraft (Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.25–28) -A dharmic model of administrative planning, delegation, feedback, and ethical appointments—anticipating modern PDCA cycles.)

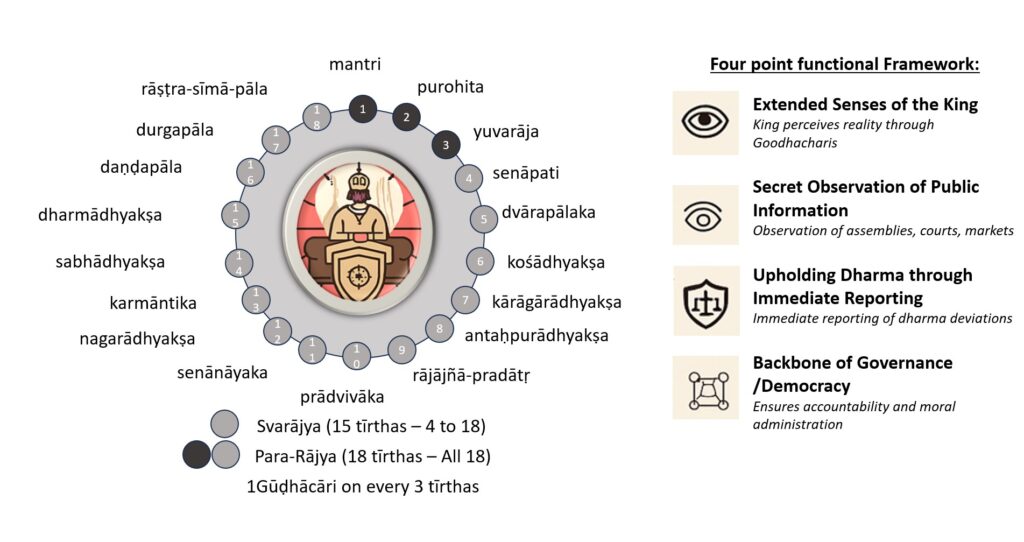

Beyond ministerial structure, Rāma’s inquiry expands into strategic intelligence and civic surveillance. Ślokas 2.100.35–37 describe the Gūḍhācāri system—a network of secret observers monitoring assemblies, markets, and courts, ensuring dharma through real-time reporting. This ancient framework mirrors modern accountability mechanisms, where information flow and ethical oversight form the backbone of governance.

(Figure 2: Gūḍhācāri Network – Backbone of Democracy (Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.35–37) -A circular intelligence system ensuring real-time feedback, dharma enforcement, and administrative integrity.)

Rāma’s vision of administration is not mechanical—it is moral. Ślokas 2.100.38–40 emphasize security and dharma as stabilizing forces, while 2.100.41–47 stress prosperity, safety, and citizen welfare. The king is not a controller but a trustee, entrusted with the well-being of his people. Governance, in this model, is sacred duty—designed not for efficiency alone, but for justice, compassion, and long-term stability.

Pillar III: Economy, Justice & Social Order

Democratic Parallel: Rule of Law & Social Equity

Rāma’s kuśala praśnas now turn to the lifeblood of the kingdom—its economic stability, judicial integrity, and social cohesion. In Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.48–51, he probes the health of agriculture and resource management, recognizing that prosperity begins with the land and its stewards. But his inquiry extends beyond production—to visibility, preparedness, and fiscal discipline.

Rāma asks:

kaccid darśayase nityaṁ manuṣyāṇāṁ vibhūṣitam | utthāyotthāya pūrvāhṇe rājaputro mahāpathe || (2.100.52)

Do you appear daily in public, adorned and accessible, strengthening citizens’ confidence and social order?

This verse affirms the symbolic power of leadership—where the king’s presence itself becomes a stabilizing force. Governance is not only about policy but about visibility, trust, and reassurance.

Rāma asks:

kaccinna sarve karmāntāḥ pratyakṣās te viśaṅkayā sarve vā punar utsṛṣṭā madhyamevātra kāraṇam (2.100.53)

I hope your attendants neither behave disrespectfully in your presence nor flee in fear—balance is best in this matter.

This verse reflects Rāma’s concern for social equilibrium and symbolic leadership. The king’s presence must inspire respect, not intimidation, and his court must maintain decorum without rigidity. It’s a subtle reminder that governance includes emotional intelligence and relational poise.

preparedness is emphasized in sloka 2.100.54: Are all forts stocked with wealth, grain, weapons, water, and skilled artisans? Rāma anticipates modern disaster-readiness and strategic infrastructure.

He asks: “āyaḥ te vipulaḥ kaccit kaccid alpataro vyayaḥ”(2.100.55) Is your income abundant and your expenditure modest? This verse encapsulates fiscal prudence—maximizing revenue while minimizing spend.

Together, these ślokas form a dharmic audit of economic and administrative health, where leadership is measured not by grandeur but by preparedness, equity, and restraint.

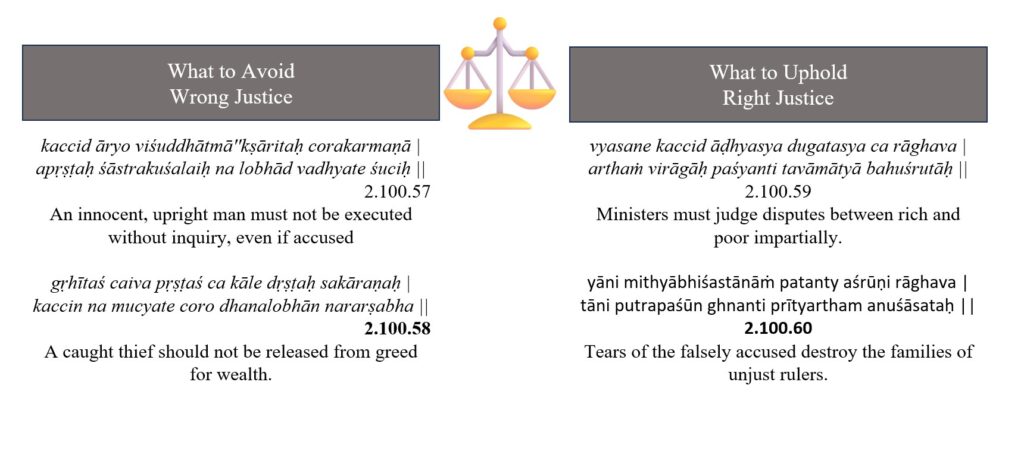

This ethic of justice deepens in verses 2.100.57–60, where Rāma warns against wrongful punishment and urges impartiality in judicial conduct. The attached figure contrasts wrong justice—driven by greed or haste—with right justice, rooted in inquiry, fairness, and compassion.

(Figure 3: Justice with Restraint – Rāma’s Counsel on Punishment (Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.57–60) – A dharmic framework for judicial ethics, emphasizing inquiry before punishment, impartiality across social strata, and protection of the innocent.)

In this model, justice is not retributive—it is restorative. Rāma’s questions reflect a deep concern for rule of law, social equity, and citizen welfare—principles that remain central to democratic jurisprudence today.

Pillar IV: Higher Ideals & Legacy of Kingship

Democratic Parallel: Participatory Governance & Long-term Vision

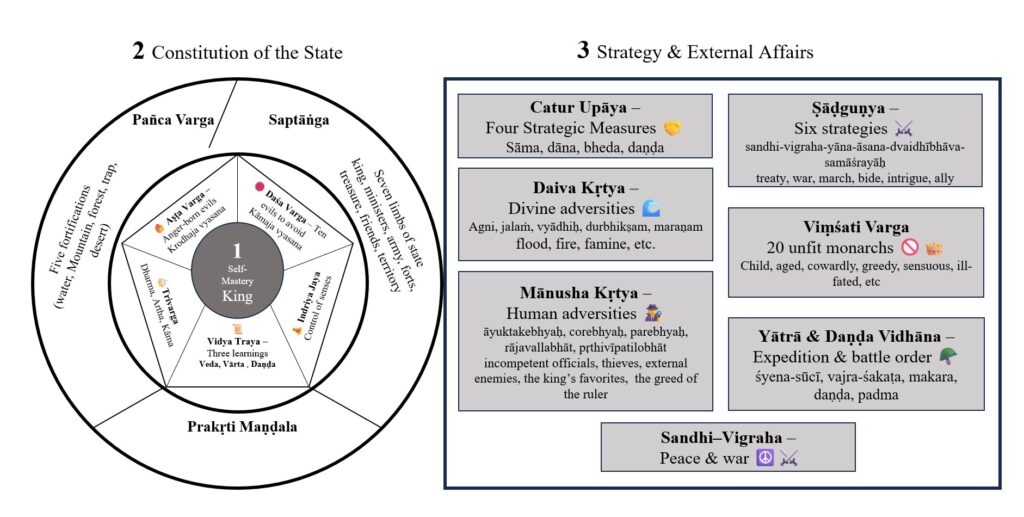

In the final arc of Rāma’s kuśala praśnas, the discourse ascends from systems to spirit—from administration to aspiration. Ślokas 2.100.63–67 articulate the ethical conduct of kingship, where rulers do not merely preach dharma but embody it. Kingship, in this view, is not a doctrine—it is a lived example, a moral presence that shapes the culture of governance.

Verses 2.100.68–71 emphasize deliberation and counsel. Rāma probes Bharata’s engagement with ministers, his openness to advice, and his capacity for reflective decision-making. This anticipates modern ideals of participatory governance, where executive authority is tempered by collective wisdom.

The closing sequence (2.100.72–76) elevates kingship to a visionary plane. Rāma urges rulers to act with foresight, inspire future leaders, and align their rule with cosmic order. Governance here transcends administration—it becomes a cultural and ethical institution, rooted in dharma and directed toward lokasaṅgraha, the welfare of all beings.

This expansive vision is visually consolidated in the following diagram, which maps the 15 Higher Ideals of Rāja Dharma from Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.69–71. The framework unfolds in three progressive layers: from spiritual attributes to constitutional structures, culminating in strategic duties—offering a dharmic blueprint for enduring leadership.

(Figure 4: Rāja Dharma – 15 Higher Ideals of Statecraft (Ayodhyākāṇḍa 2.100.69–71)

A comprehensive framework of ethical kingship, integrating wisdom, humility, valor, and skill with strategic foresight, social responsibility, and cosmic alignment.)

In this model, the king is not merely a ruler—he is a custodian of culture, a guardian of dharma, and a visionary architect of the future. Rāma’s praśnas culminate in a timeless ideal: leadership is sacred only when restrained by law, shared through counsel, and directed toward the welfare of all.

Rājadharma in Vanavāsa: Forest as Alternative Rājya

Rāma’s exile is often viewed as a narrative of suffering and endurance, yet within the Indic political imagination, it assumes deeper meaning. He does not treat the forest as a place of abdication, but as an alternative rājya—a symbolic polity. Though stripped of palace, throne, and court, he never relinquishes the responsibilities of kingship. By carrying dharma into the wilderness, Rāma affirms that rājadharma is not throne-dependent but dharma-dependent—an ethical responsibility that transcends institutional trappings.

The forest, in this sense, is a microcosm of disorder. Populated by sages, ascetics, tribes, and marauding rākṣasas, it represents a society at the margins—unsettled and vulnerable. In protecting hermitages, punishing lawlessness, and upholding truth amidst adversity, Rāma transforms Daśaratha’s command into a deeper mandate—not merely to dwell in the forest, but to uphold rājadharma within it. He interprets his father’s instruction not as withdrawal from kingship, but as a call to preserve its essence in a new setting. In doing so, he treats the forest not as a site of exile, but as a dharmic polity—governing not through titles, but through moral authority and protective action.

His rājadharma adapts to context but does not diminish. Leadership here is exercised not through institutional power, but through ethical presence and responsive action.

This redefinition of kingship as portable dharma carries profound implications for political philosophy. Sovereignty is not a static possession, but a living covenant of responsibility. A ruler may lose the external signs of power, yet remain a king if he embodies justice, compassion, and steadfastness to truth. Conversely, one who occupies the throne without these principles is no true sovereign.

In this light, Rāma’s conduct offers a model of leadership as role rather than position. Kingship becomes a mobile ethic, exercised wherever circumstances demand the preservation of order and the defense of dharma. By treating vanavāsa as an opportunity to affirm rather than suspend his duties, Rāma transforms personal misfortune into a universal lesson: that political authority is ultimately rooted in ethical responsibility, not institutional privilege.

Synthesis: Rāma’s Framework of Dharmic Leadership

The Citrakūṭa dialogue between Rāma and Bharata emerges as a seminal text on rājadharma, offering profound insights into leadership, governance, and ethical responsibility. Far from being a mere episode of familial reunion, this encounter transforms private affection into a medium for public instruction—demonstrating that statecraft is inseparable from moral and relational grounding. Framed through kuśala praśna, Rāma’s discourse codifies principles spanning personal discipline, ministerial counsel, judicial fairness, security, economic welfare, and the pursuit of higher ideals—establishing a holistic template for righteous governance.

Crucially, Rāma redefines kingship as an ethical vocation rather than a throne-bound privilege. The forest, though beyond palace walls, becomes an extension of Ikṣvāku sovereignty—a dharmic polity where Rāma enacts kingship through moral authority and protective action. Leadership, therefore, is portable, situational, and continuously accountable to moral and cosmic order.

Taken together, these four pillars reveal how Rāma, through fraternal dialogue, distilled a comprehensive architecture of statecraft. His kuśala praśnas weave together personal ethics, administrative order, economic justice, and visionary leadership—mapping seamlessly onto principles that remain central to democratic governance today.

(Figure 5: Four Pillars of Statesmanship – Rāma’s Kuśala Praśnas mapped to modern democratic principles – A thematic synthesis of ethical leadership, governance, justice, and visionary kingship drawn from Ayodhyākāṇḍa Sarga 100.)

This architecture is not merely theoretical—it is pedagogical. Through the Citrakūṭa encounter, Rāma enacts a threefold process of political instruction: testing Bharata’s ethical fitness, teaching the Ikṣvāku framework of governance, and transforming his grief into public responsibility. This progression—Testing, Teaching, Transforming—reveals that statecraft in the Indic tradition is not imposed but awakened. It is transmitted relationally, through saṁvāda, and anchored in lineage, emotion, and dharma.

(Figure 6: Rāma’s 3T Model of Political Instruction at Citrakūṭa – Testing, Teaching, Transforming – A pedagogical arc of ethical transmission through fraternal dialogue and dharmic responsibility.)

Conclusion

In this light, the Citrakūṭa dialogue is not a pause in the epic—it is its political heart. Through fraternal exchange, Rāma transforms grief into guidance, affection into instruction, and forest life into ethical affirmation. The encounter offers a timeless model of governance: grounded in virtue, guided by counsel, and elevated by vision. His kuśala praśnas remain as relevant today as they were in Citrakūṭa—a blueprint for leadership that is ethical, participatory, and enduring.

त्वं राजा भरत भव स्वयं नराणां वन्यानामहमपि राजराण्मृगाणाम् ।

गच्छत्वं पुरवरमद्य सम्प्रहृष्ट: संहृष्टस्त्वहमपि दण्डकान् प्रवेक्ष्ये ।।

tvaṃ rājā bharata bhava svayaṃ narāṇāṃ vanyānāmahamapi rājarāṇmṛgāṇām ।

gacchatvaṃ puravaramadya samprahṛṣṭa: saṃhṛṣṭastvahamapi daṇḍakān pravekṣye ।।

(You, Bharata, be the king of men; I shall be the sovereign of forest beings.

Go joyfully to the city today, And I too shall enter Daṇḍakāraṇya with joy.)

References

- Śrīmad Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇam, Ayodhyākāṇḍa, Gīta Press, Gorakhpur Edition

- valmikiramayan.net (online text of Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa)

(Acknowledgements: I am deeply indebted to Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, whose guidance has been instrumental from the very conception of the title to shaping every step of this essay. His insights on balancing traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives have been invaluable throughout this work. I also wish to thank Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions and perspectives, which enriched the clarity and depth of the essay. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge my daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), for her thoughtful editorial review and aesthetic refinements, which gave the essay its final polish.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.