Vāyu Tattva: Śrīkālahasti — Where Every Breath is Worship

प्राणो हि भूतानामायुर्व्याप्तं सर्वत्र शाश्वतम् ।

तं वायुमीश्वरं वन्दे श्रीकालहस्तिनायकम् ॥

prāṇo hi bhūtānām āyur vyāptaṁ sarvatra śāśvatam |

taṁ vāyum īśvaraṁ vande śrīkālahastināyakam ||

(Prāṇa is indeed the life of all beings, pervading everywhere, eternal.

I bow to that Lord as Vāyu, Śrīkālahastināyaka.)

Of the five sacred abodes where Śiva reveals himself as the Pancha Bhootas, four, I have been blessed to walk into, breathe, and surrender—Chidambaram as the kshetra with unforgettable memories of my mother, Tiruvannamalai as Pita Kṣhetra, Kanchipuram as Guru Kshetra, and Tiruvanaikaval as the kshetra for Deivam. But Śrīkālahasti remains, for me, an agñāta kṣetra—an unknown shrine, a temple I have not yet stepped into.

Perhaps it is only fitting, for this is the Vāyu sthala, where Śiva is present as air, the unseen breath that pervades both the body and the cosmos. How can one claim to “see” that which is invisible, all-pervading, and beyond grasp? Maybe the Lord wills that I first acknowledge this unknowing, this mystery—that I gather the outer knowledge before I enter the sanctum of direct experience. In this pause, there is a quiet teaching: that not all shrines are meant to be known through sight and touch alone. Some ask that you first breathe them in as wonder, as awe, as the unseen presence that already surrounds you.

And yet, as I read and learn more about Śrīkālahasti, the shrine seems to rise before my mind’s eye. Though my feet have not touched its stones, I can almost see the temple standing amidst rugged hills, the Suvarnamukhi river curving at its feet, and the sanctum breathing with the unseen presence of air. It is as if the very act of knowing draws me closer, allowing me to glimpse in imagination what awaits in experience. I do not know if I am dreaming or consciously visualising, but this is what I envision about Śrīkālahasti.

Amidst the rugged hills and the serpentine course of the river Suvarnamukhi, I can almost visualise Śrīkālahasti rising before me—the temple of breath itself, the vāyu sthala, where the element of air is worshipped as Śiva. Though I have not yet set foot there, its presence feels alive within me: the unseen current of wind that moves the trees, the invisible force that sustains life, the eternal reminder that every breath is sacred. If Chidambaram is the secret sky, Arunachala the blazing fire, and Ekāmranātha the steadfast earth, in Kalahasti the Lord moves as the unseen force. The flicker of the ever-burning lamp within the sanctum, swaying gently without extinguishing, is said to be the eternal witness to this mystery—the presence of air without beginning or end.

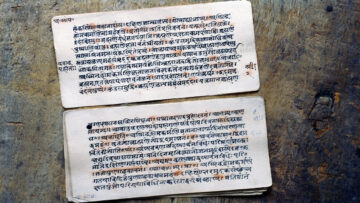

(Figure 1: Sri Kalahasti Temple, Srikalahasti, Andhra Pradesh)

At Śrīkālahasti, the presiding deity is Śrīkālahastīśvara (a form of Śiva) worshipped as the Vāyu Liṅga, representing the element of Air. His consort is Gnāṉaprasūṉāmbikai (Jñānaprasūṉāmbā), whose very name means “She who blossoms as knowledge/wisdom.” The sthala is one of the few where the Devi’s name itself carries the idea of inner realization.

(Figure 2: Sri Kalahasti Temple)

Legends of Śrīkālahasti — The Breath of Devotion

When one speaks of Śrīkālahasti as the Vāyu sthala, it is not merely to mark an element but to honour the very mystery of breath itself. The liṅga enshrined here is said to be svayambhu, self-born, unlike any other. Made of white stone resembling camphor, it is never touched by human hands. Priests pour their offerings over it, but the liṅga itself remains beyond touch, as if reminding us that air, like prāṇa, is untouchable—only felt, never grasped. The ever-burning lamp beside it flickers ceaselessly, though no wind stirs in the sanctum, a testimony to Śiva’s presence as breath, eternal and unseen.

It is said that Vāyu himself once worshipped this liṅga with unswerving devotion. From him arose the camphor-like form, white and translucent, that radiates the fragrance of the unseen. As breath sustains every creature, so too does this liṅga embody Śiva as the ungraspable yet indispensable. One cannot bind air, yet one lives only because of it. In this, Śrīkālahastīśvara becomes the reminder that the most essential truths are not those we touch with our hands, but those that silently course through us with every breath.

If the svayambhu liṅga of camphor at Śrīkālahasti reveals Śiva as the unseen breath—intangible yet ever-present—then the legend of Pārvatī reminds us of how that breath draws the seeker back into union. Every divine leela holds a lesson, discernible when we look past the story to its esoteric core.

Once, the Divine Mother Pārvatī was playfully distracted in Śiva’s presence. In some retellings, she is said to have closed Śiva’s eyes with her hands—an innocent act, yet one that plunged the three worlds into darkness for a moment. In another version, she incurred a curse from Śiva for having been momentarily negligent during worship. In both strands, the outcome was the same: she was cursed to be born with a mortal form, a separation from her Lord.

The place chosen for her penance was none other than Śrīkālahasti. Why here? Because only in this vāyu sthala—where the liṅga itself is pure, untouchable, self-existent, and pervaded by the essence of prāṇa—could her austerities bear fruit. It is said that she fashioned a liṅga of sand and worshipped it with steadfastness, standing in silence, her breath itself becoming the offering.

Her penance was so intense that Śiva appeared before her and absolved her of the curse, blessing her with eternal presence by his side as knowledge.Gnānappūnambal (or Gnānaprasūnambikā) in Śrīkālahasti. Thus, in this sthala, she is not only consort but also the symbol of śakti reunited with śiva through the transformative power of tapas. Yet Pārvatī’s story at Śrīkālahasti does not end with reunion—it flowers into something more profound, revealed in the very name by which she is worshipped here.

The name itself means “She who is the blossom (prasūna) of wisdom (jñāna).” In the legend, after Pārvatī’s penance at Śrīkālahasti and her reunion with Śiva, she was not only restored as consort but also revealed in her aspect as the giver of true wisdom.

Here, she is not seen as merely the embodiment of beauty or maternal grace, but as the flowering of inner wisdom that blossoms in the heart of the seeker. Just as fragrance cannot be separated from a flower, wisdom cannot be separated from the Mother; she radiates it naturally, without effort.

It is said that those who worship Gñānaprasūnambikā are granted clarity of thought, the removal of ignorance, and the flowering of insight—jñāna that is not just intellectual, but transformative. In Śrīkālahasti, where breath itself is worshipped, she becomes the wisdom that arises from stillness, the knowledge born when prāṇa is sanctified.

This aspect of the Divine Mother as the blossoming of wisdom is not only symbolic but also enshrined in legend. For it was here, at Śrīkālahasti, that she is said to have bestowed upon the boy-sage Mārkaṇḍeya the jñāna pāl—the very milk of knowledge. Just as a mother feeds her child, she nourished him with wisdom itself, affirming her role as Gñānaprasūnambikā. In this way, the Devi does not merely bless from afar; she enters into the life of the devotee, sustaining them with the essence of jñāna, the only nourishment that is eternal.

If Mārkaṇḍeya’s story reveals how the Devi nourishes the seeker with wisdom, the tale of Kannappa shows that devotion needs no learning, no refinement. For here at Śrīkālahasti, both the sage and the hunter are embraced equally. One was steeped in knowledge, the other in instinct; yet both found fulfillment at the same liṅga, for Śiva does not discriminate between the polished and the raw when the heart is true.

The story of Kannappa is among the most moving in Śrīkālahasti. He was a hunter by birth, unlettered in the ways of ritual, yet his heartbeat with unshaken love for Śiva. When he discovered the liṅga in the forest, he began to worship in the only way he knew—offering the choicest pieces of his hunt, pouring water from his mouth when he had no vessel, adorning the Lord with leaves and flowers plucked straight from the wilderness.

To the priests, these acts seemed crude, even defiling. Yet to Śiva, they were the highest form of devotion. For Kannappa’s love was not bound by convention; it was spontaneous, fierce, and total.

One day, as he worshipped, Kannappa saw blood flowing from one of the liṅga’s eyes. Without hesitation, he plucked out his own eye and placed it upon the liṅga. When the second eye began to bleed, he prepared to offer his other eye as well—his very life, without a second thought. At that moment, Śiva himself appeared, halting the act and embracing Kannappa as his truest devotee. He was given a place among the sixty-three Nayanmars and is remembered as the very embodiment of unselfconscious, absolute devotion.

(Figure 3: Sri Kannappa)

In Kannappa’s story, Śrīkālahasti reveals another face of the divine mystery: if to Mārkaṇḍeya it was the gift of wisdom, to Kannappa it was the recognition of love beyond measure. The sage and the hunter—two extremes—meet in this vāyu sthala, where breath itself is worshipped, and both find acceptance in the heart of Śiva.

If Kannappa’s tale shows how the Lord treasures a single-hearted offering, the legends of the spider, the serpent, and the elephant show that even across the vast spectrum of life—instinctive, protective, or forceful—devotion wears many forms. In Śrīkālahasti, it is said that creatures as different as these three found liberation, proving that what matters is not the manner of worship but the sincerity behind it.

In the forest surrounding Śrīkālahasti, three unlikely worshippers turned to Śiva in their own ways: an elephant, a spider, and a serpent.

The elephant, strong and earnest, expressed his devotion through service. Each day he would gather water in his trunk, bathe the liṅga, and adorn it with fresh flowers. His worship was majestic, simple, and steadfast—offering strength and purity at the feet of the Lord.

The spider, fragile and small, built a web around the liṅga—not to conceal it, but to protect it from the falling leaves and dust of the forest. To him, the act of weaving a shelter was devotion, each thread spun with care, his very body offered in service.

The serpent, fierce and watchful, coiled itself around the liṅga to guard it from harm. Its worship was vigilance, its devotion expressed as protection born of instinct.

Yet, because their natures were so different, conflict arose: the elephant’s water-worship destroyed the spider’s web, while the serpent, enraged at the elephant’s constant bathing, struck at him. In the struggle, all three lost their lives. But Śiva, moved by their sincerity, granted each of them mokṣa, liberation.

Thus the Lord of Kalahasti became known as the one who accepts worship in every form—whether it is the elephant’s strength, the spider’s subtle care, or the serpent’s fierce vigilance. What matters is not the form, but the intent, not necessarily the ritual, but the heart.

In Śrīkālahasti, breath itself is sacred, yet it is not only in air that the divine is felt. Here, wisdom flowers through Gñānaprasūnambikā, devotion takes shape in the hunter Kannappa, and the spectrum of life itself—the spider, the serpent, the elephant—finds liberation in the simplest acts of sincerity. Each legend is a different note in a single hymn: the unseen becomes visible, the ordinary becomes sacred, and every being—learned or instinctive—is drawn into the eternal rhythm of prāṇa.

I sense the wisdom in every story, in every breath that moves through it, in every act of love and surrender. Śrīkālahasti waits, not merely to be visited, but to be experienced: the wind that bends the trees, the flicker of the lamp that knows no beginning or end, and the quiet, unspoken devotion that unites sages, hunters, and creatures alike. It is a place where knowledge and love, effort and instinct, all meet in the sacred breath of the Lord.

And yet, Śrīkālahasti is not only the sthala of wind and breath, nor merely the stage of legends woven with sages and hunters. It is also the parihāra kṣetra where shadows themselves are worshipped into light. For here, the restless forces of Rāhu and Ketu—the eclipse-makers, the karmic knots—are acknowledged and appeased. To speak of Śrīkālahasti fully is to speak not just of breath, but also of shadow, for only in their union does the mystery of this temple come alive.

Unlike the visible grahas, Rāhu and Ketu are points of absence. They have no bodies, yet they wield immense power because they mark the spots where the orbits of the Sun and Moon intersect. Whenever the Sun or Moon comes near these nodes, an eclipse occurs. Thus, Rāhu and Ketu literally “swallow” the luminaries, enacting in the sky the drama of shadow overcoming light.

Astrologically, this is why they are associated with karmic knots. Rāhu represents those desires that eclipse reason, drawing the soul into experiences it cannot resist. Ketu represents the shadows of past lives, the unfinished business of memory, pulling one back into detachment or sudden loss. Together they form the axis of eclipse in the chart—the places where the soul is tested through both worldly entanglement and forced renunciation.

(Figure 4: Rahu Ketu Parihara)

In this sense, Rāhu and Ketu are not enemies of the Sun and Moon, but their necessary counterparts—reminding us that light without shadow is incomplete. They embody the law of karma in its most relentless form: what is hidden must emerge, what is eclipsed must be faced.

Why, then, is Śrīkālahasti remembered as the parihāra sthala for Rāhu and Ketu? Perhaps it is because this is the temple where shadows themselves are given sanctuary. The very nature of these grahas is airy and formless, born of division, forever restless—how fitting, then, that they should find repose in the vāyu kṣetra, where the unseen movement of breath is worshipped as Śiva. To stand before the liṅga here is to realize that even what cannot be grasped can be held in reverence, even what unsettles can be stilled.

The legends, too, whisper of this inclusiveness. The spider, the serpent, the elephant, the hunter Kannappa—beings far removed from the orthodox path—were all embraced and redeemed here. Rāhu and Ketu, severed shadows cast aside by the Devas, are no different. At Śrīkālahasti, even the outcast, the restless, the fragmented, is made whole in the presence of the Lord.

And what is an eclipse, if not a shadow passing over light? In the rituals here, that moment of cosmic disturbance is mirrored and then resolved: the devotee names Rāhu and Ketu, acknowledges the eclipse within their own life—be it in health, love, or destiny—and offers it into the fire of Śiva. The darkness is neither denied nor feared; it is consecrated, turned into a step towards clarity.

This is why, even today, pilgrims arrive from every corner seeking Rāhu–Ketu śānti. The priests of Śrīkālahasti do not merely preserve a myth but carry forward a living tradition, crafting rituals that soothe the anxieties of modern lives while echoing the timeless truth: that shadow and light alike move in the rhythm of breath, and both can be sanctified.

I await the day when Kālahastīśwara and Jñānaprasūnambikā grant me the wisdom to walk this world with grace—to partake of its delights without being bound, to breathe its air without clinging, to live amidst shadow and light yet remain steady in the Self. Perhaps that is the true gift of Śrīkālahasti: to teach that every breath is worship, and every moment, when lived with awareness, becomes liberation.

History, Architecture, and the Living Temple

Śrīkālahasti’s story is not just written in legend but also in stone, inscription, and dynasty. Though its earliest references go back to the Pallava period, it was the Cholas who first gave lasting shape to the temple in the 10th century. Later, the Vijayanagara kings, particularly Krishnadevaraya in the early 16th century, expanded and adorned it with the majestic gopuram, towering nearly 120 feet. That gopuram, damaged in recent years, still rises in reconstructed strength, a reminder of how the temple—like the breath it embodies—renews itself across ages.

Within its vast prakāras, every mandapa tells a tale. The hundred-pillared hall stands as a marvel of Vijayanagara artistry, its pillars alive with intricate carvings of gods, dancers, and mythic motifs. The inscriptions here are not cold records but voices of history—donations of land, endowments for lamps and rituals, the devotion of kings and commoners etched side by side. In these halls, dynasties may have come and gone, but their prayers remain, frozen in script yet still warm in intent.

At the heart of it all lies the sanctum, encircled by koshtas—living deities carved into stone, each adding a dimension to the Lord’s presence. To the south is Dakṣiṇāmūrti, the silent teacher who grants wisdom without utterance. On the west wall is Liṅgodbhava, the fiery column that revealed Śiva’s infinitude to Brahmā and Viṣṇu. To the north stand both Viṣṇu and Brahmā, creation and preservation bowing to the breath that sustains them. Nearby, Gaṇapati welcomes all who enter, and Subrahmaṇya radiates youthful grace. The Navagrahas too have their place, most fitting in a temple where Rāhu and Ketu are ritually appeased. Even today, Śrīkālahasti is not a monument of the past but a temple of the present, where the ancient rituals of Rāhu–Ketu parihāra continue to draw seekers from across the land. The continuity of this practice is a reminder that the temple breathes not only in its stones but in the hopes and prayers of those who come seeking release from unseen shadows. And by Śiva’s side is Gñānaprasūnambikā, the Mother who nourishes not with grain or fruit, but with the milk of wisdom blossoming in the heart.

To the passing eye, one gopuram may look like another, one mandapa like the last. Yet every temple is singular in its energy. At Śrīkālahasti, the breath itself becomes sacred—the wind that rustles the trees, the unseen force that keeps the lamp aflame, the hush that pervades the stone corridors. Every grain of sand here is charged with the prayer of someone who once stood at the threshold of despair or hope. Each step is layered with centuries of surrender. A tourist may see towers and carvings, but the seeker feels something different: the temple gives what the heart longs for, if only one arrives with humility and the courage to lay oneself bare.

And yet again, I find myself yearning to walk those very corridors, to stand before Kalahastheeswara and Gñānaprasūnambikā, and to feel for myself the pulse of this kṣetra. Until that day, I carry the temple within—as vision, as breath, and as promise.

Antiquity of Śrīkālahasti

The antiquity of Śrīkālahasti is not only etched in stone but whispered in legend. It is said that Brahma himself first worshipped Śiva here, seeking release from the weight of creation. The Pandavas too, in their years of exile, are believed to have prayed in this kṣetra—Yudhishthira for strength, Arjuna for mastery, each finding in the Lord of Air the steadiness needed to face destiny. Markandeya is remembered here as well, nourished by the milk of wisdom from Gñānaprasūnambikā, affirming the temple’s place as a sanctuary where the human meets the eternal.

If the Purāṇas speak of the temple as timeless, history anchors it in record. Inscriptions of the Chola kings—Rajendra Chola, Kulottunga, and others—reveal grants, endowments, and reverence that stretch back a thousand years. Vijayanagara kings, most notably Krishnadevaraya, left their indelible mark in the early sixteenth century, building the hundred-pillared hall and the towering gopuram that still dominates the skyline. Every dynasty, every inscription, is a reminder that Śrīkālahasti was not just revered but continually renewed.

And yet, perhaps its deepest antiquity lies not in kings or inscriptions, but in song. Śrīkālahasti is one of the sacred Pādal Petra Sthalams, enshrined in the Tevāram hymns of Sambandar, Appar, and Sundarar. In their voices, the unseen air became intimate—Śiva was the breath within, the liberator who disperses karmic fetters as easily as wind scatters clouds. To know that these saints once stood where I long to stand is to feel already connected, carried by their breath of praise. Later, Arunagirinathar too sang of this sthala in his Tiruppugazh, reminding us that the current of devotion here is not bound to one stream but flows wide, embracing all who enter.

Every stone and inscription preserve a memory; every record adds to its grandeur. Yet what sets Śrīkālahasti apart is not just its antiquity, but its breath — the eternal flame in the sanctum that trembles without pause, though no wind is felt. It is said to be the very presence of Vāyu, the unseen proof that this kṣetra still breathes, carrying forward the pulse of devotion through centuries.

Festivals, Community, and the Living Breath of Śrīkālahasti

Śrīkālahasti is not only a shrine of myth and antiquity, but also a vibrant center of living tradition. Its pulse is most powerfully felt during Mahā Śivarātri, when thousands of devotees gather through the night in vigil, chanting hymns and pouring their hearts into the feet of Kalahastheeswara. The temple comes alive in a rhythm of music, dance, and light, echoing the timeless union of Śiva and Śakti. The festival is not merely ritual but renewal, when the winds around the temple seem to thrum with collective devotion.

Equally significant is Kārttika Dīpam, when lamps are lit in unbroken rows, mirroring the eternal flame within the sanctum. Pilgrims also flock here on days considered astrologically charged, when parihāra for Rāhu and Ketu draws seekers from across the land—each carrying hopes for relief, for clarity, for a fresh chapter in their destiny.

Around these rituals unfolds a social fabric woven by faith. The temple sustains not only priests and ritual specialists, but also astrologers, musicians, artisans, and humble vendors of flowers, lamps, and prasāda. Generations of families have tied their lives to its rhythm—some as guardians of its traditions, others as witnesses to the steady stream of pilgrims whose stories intermingle with their own. Here, devotion is livelihood, and livelihood is sanctified by devotion.

Economically too, Śrīkālahasti is a pilgrim town, where each offering of coconuts, every garland of bilva leaves, every scroll of horoscope becomes part of a sacred economy. The town breathes because the temple breathes. For the weary traveler, the sight of small homes adorned with kolams, the fragrance of camphor mingling with jasmine, the steady ringing of bells—all of it becomes as much a darśan as the deity himself.

And always, the landscape holds the shrine in a quiet embrace. The Swarnamukhi River, flowing nearby, has for centuries washed the feet of this kṣetra, its waters carrying both legend and life. The hill that rises behind the temple frames it like a guardian, reminding the pilgrim that this is not an isolated shrine but one woven into the very geography of sacred India.

To one who comes with a heart open, Śrīkālahasti offers not only relief from affliction but also a vision of how the spiritual, the social, and the earthly entwine. It is a reminder that every gopuram may look the same to the tourist’s eye, but each kṣetra sings its own note, gives its own prasad, and reveals precisely what the seeker is ready to receive.

I have taken this journey through the Pancha Bhūtas — Pṛthvī, Agni, Ākāśa, Āpas, and Vāyu. Each element revealed itself not only in stone and sanctum, but in the pulse of devotion, the rhythm of the landscape, and the breath of the devotees.

Chidambaram, the Mātā sthalam, taught me the vastness of sky, the silent expanse of the mother principle, and the subtle wisdom of surrender. Tiruvannamalai, the Pitā kṣetra, ignited in me the steady fire of fatherly guidance — discipline, protection, and the grounding warmth of dharma. Ekāmranātha at Kānchi, my Guru sthalam, revealed the unwavering earth of knowledge and instruction, the patience and clarity that only the Guru can provide. Thiruvanaikaval, as Deivam, showed me the flowing waters of grace, the living compassion that sustains life and nurtures devotion.

Śrīkālahasti, the Vāyu sthalam, remains an agñāta kṣetra in my experience, yet it whispers its presence in every story, in the breath of the wind, in the flicker of the eternal flame. Here, I sense the invisible force that moves through all life — the element of air, prāṇa itself — reminding me that the journey is not only outward, but inward, and that the unseen can be the most profoundly present.

There are many more sacred energies to explore beyond these five, yet each temple, each sthala, grants the devotee what the seeker is ready to receive. Every kṣetra has its Sthala Purāṇa, its history, years of dedication visible in architecture, antiquity, and the devotional and mythic tales of sages and seekers who walked there. To step onto the same soil, to breathe the air they breathed, is devotion itself. If only the rocks and the sand could speak… The icons, the mūrthies, they do speak, but one must surrender fully to listen. We see them in form, yet they remain formless…

And here, the truth of the formless reveals itself in Śaṅkarācārya’s words:

ना च प्राणसङ्ग्यो न वै पञ्चवायुः।

न वा सप्तधातुर् न वा पञ्चकोशः।

न वाक्पाणिपादौ न चोपस्थपायुः।

चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम्॥

na cha prāṇasaṅgyo na vai pañchavāyuḥ

na vā saptadhātur na vā pañchakōśaḥ

na vākpāṇipādau na chopasthapāyuḥ

chidānanda rūpaḥ śivō’ham śivō’ham

(I am not the vital life force, nor the five winds;

I am not the seven elements, nor the five sheaths;

I am not speech, hands, feet, or the organs of action;

I am pure consciousness and bliss — I am Śiva, I am auspiciousness.)

To read this in the quiet, to breathe it in as one would the wind through Śrīkālahasti, is to realize that all the temples of the Pancha Bhūtas, with their histories, legends, and devotion, point toward the same ultimate truth: that the formless pervades all forms, and that surrender is the heart of devotion. Each element, each sthala, each deity — Mātā, Pitā, Guru, Deivam, and Vāyu — offers its own teaching, yet all converge in the recognition that the essence of the sacred is beyond form, beyond story, beyond ritual — and entirely within reach of the seeking heart.

This is only the beginning — a single drop in the vast ocean of Sanātana Dharma. The end is nowhere in sight; it will take more than a lifetime to truly experience the sacred geography of Bhārat. I consider this a first step, and I invite you, dear reader, to continue on this journey with me — to walk, to breathe, to listen, and to surrender to the timeless presence that pervades every sthala.

(Acknowledgement: I gratefully acknowledge the many resources, both online and in print, that have provided valuable information on the legends, history, and traditions of Śrīkālahasti. While this work is written in my own voice and with my reflections, I remain indebted to the scholars, devotees, and keepers of tradition whose efforts in preserving and sharing knowledge have guided me on this journey. I also extend my heartfelt thanks to the editors of Indica for offering me a platform to undertake and share this pilgrimage in words.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.