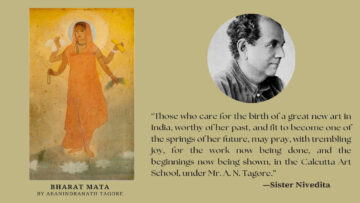

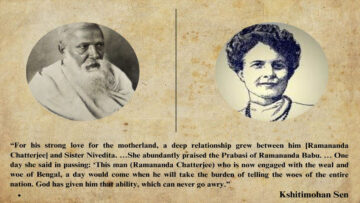

Even today, people admire Ramananda Chatterjee, the founder-editor of both Prabasi and Modern Review, as the father figure of Indian journalism. According to Sankari Prasad Basu, no one can match what Ramananda Chatterjee did through his magazines for the art movement in India and the budding artists of his time. Ramananda first started the Bengali magazine Prabasi in Allahabad and published paintings of young talents to bring them to the public’s attention and satisfy his passion for art. Later, when he began the Modern Review in 1907, it followed the same tradition with even greater enthusiasm. Sister Nivedita was a friend of Ramananda, and she regularly contributed articles, translations, notes, and other works to the Modern Review, unfailingly keeping India and its people as the central theme. Abanindranath Tagore once said that the vast publicity of Indian art evident during their time could never have been possible without Ramananda Babu’s efforts. He worked hard, spent money, and created demand among the public to make Indian art accessible to everyone.

Ramananda Chatterjee had made Ravi Varma and MV Dhurandhar well known or popular in Bengal. But in later years, he changed his initial opinion about them. Nonetheless, his love and admiration for Indian art seemingly lacked the keen sense or expertise needed to evaluate them in critical perspectives; on many occasions, this led him to accept the European views or opinions in judging the country’s art. The change came after his friendship with Sister Nivedita. Ramananda did not hesitate to acknowledge how this change came upon him: “I had once been a staunch supporter of Ravi Varma and his group of artists. The biography I once had written on him still sells in the market and thus I am indebted to him. About 5 to 6 years back, I had even written an agitated letter to late Sister Nivedita upholding Ravi Varma’s paintings. In reply to my letter, that immensely wise lady penned a thirty-two-page reply—though with hindsight she decided against sending that to me. Perhaps it is still lying with Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose. Later on, I heard from the departed lady that she had not sent it to me as she thought that through viewing more and more of paintings I would gradually be convinced of the essentials, which no number of arguments could do. I do not know whether I have become able to judge the essentials yet, but I have become a connoisseur of those kinds of paintings which she had liked.”

(Figure 1: Credit: Wikipedia – A scene from Mahabharat, a painting by Ravi Varma)

This reminds us of what Rabindranath Tagore reminisced much later in the Prabasi while referring to the period when the paintings of Ravi Varma first appeared: “… At that point of time we saw the paintings of Ravi Varma—and were excited, I must say. Our minds were not ready to understand that they were imitations, akin to the dressed actors of the indigenous opera party. I express my indebtedness to [EB] Havell for getting us out of that shameful ignorance.”

About EB Havell, we shall write in time. Right now, the Sister’s association with the Modern Review asks for a relook. As our primary focus is on her contribution to the Indian art movement, we must leave aside her other writings in the Review. But what Ramananda Chatterjee wrote in Nivedita’s obituary reflects her significant contributions as a whole: “From the very birth of this Review, she helped us with her contributions and suggestions and in other ways in an uncommon measure…. She was indeed a sister and she was nivedita, dedicated to the service of all who came within the orbit of her life’s way.”

(Figure 2: Credit: Wikipedia – Cover page of “Prabasi Bengali Magazine”)

About what Nivedita did in appreciating and promoting Indian Art, Ramananda Chatterjee has left no ambiguity, he writes: “She seemed to have an almost instinctive appreciation of the artistic. Great and noble ideas beautifully expressed through the medium of painting, sculpture or architecture made an immediate appeal to her aesthetic sense. She did much to interpret our Art to us and the West alike. In the same way she interpreted to us many of the great European works of art through the medium of this Review and the Bengali Magazine Prabasi. Her writings in this line, though brief, were often unique. One gem we are reminded of as we write—that in which she spoke to us of Abanindranath’s Passing of Shah Jahan. She told us she was proud of it, and well she might be. It is great as a pen-picture, as the Painting is as a creation of the brush. This leads us to observe that though she usually moved in an atmosphere of Hinduism [,] she was not wanting in an appreciation of the good points of Islam and Islamic civilization.”

After long years, when writing in the Modern Review on Ramananda Chatterjee after his demise, historian Jadunath Sarkar remembered the contribution of Sister Nivedita: “Among the most frequent and valued contributors up to the time of her death in 1911 was Sister Nivedita, and even after her sad departure from our midst, her unpublished papers continued to adorn the pages of The Modern Review till they came to an end. She converted educated India to the recognition of the true principles of art, and also instructed the new school of Indian Art in Bengal by her wise criticism of their paintings. This Indian art became the special feature of The Modern Review.”

(Figure 3: Credit: Wikipedia – 1934 edition of “The Modern Review”)

The Modern Review became the conduit for Nivedita to inspire and influence the sceptics within the country and the chauvinistic West about India’s undying spiritual and intellectual wealth. She wrote an incredible number of articles and essays in the journal for about five years between 1907 and 1911, barring numerous editorials and other writings which do not carry her name. But the fact is, her first writing in the inaugural number of the Modern Review (January 1907, which continued in February 1907 number too) is on art, titled The Function of Art in Shaping Nationality, wherein she wrote: “… Art offers us the opportunity of a great common speech, and its rebirth is essential to the upbuilding of the motherland. Its re-awakening rather.” And a little later, in the same essay, she added words of her conviction: “Art…is charged with a spiritual message—in India today, the message of the Nationality. But if this message is actually to be uttered, the profession of the painter must come to be regarded, not simply as a means of earning livelihood, but as one of the supreme ends of the highest kind of education.”

(Read more in Part 4 – Sister Nivedita and Ramananda Chatterjee: An Association of Enduring Impact)

References and Notes

- Sankari Prasad Basu, Nivedita Lokmata, vol. 4 (Kolkata, Ananda Publishers, Beng. 1401), p. 131.

- Abanindranath Tagore, Bharatiya Chitrakalar Prachare Ramananda, Prabasi (Poush,1350), p. 261 (See Nivedita Lokmata, Sankari Prasad Basu; vol. 4, p.132)

- Ramananda Chattopadhyay, Prabasi Itihaser Dhara: Miscellaneous Topics and a Compilation (Kolkata, Ratnabali, 1990), volume 2, pp. 483-84 (Editorial comment to the article ‘Bharater Prachin Chitrakala’ by Ramaprasad Chanda in Aghrayan 1320. Translated from Bengali).

- Prabasi Itihaser Dhara., volume 2, p. 319 (EB Havell, by Rabindranath Tagore in Magh 1345. Translated from Bengali).

- The Modern Review, November 1911, 517, and 338.

- The Modern Review, November 1943, 338 (See Ramananda Chatterjee: India’s Ambassador To The Nations, Sir Jadunath Sarkar).

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.