नमो भगवते तस्मै कृष्णायाद्भुतकर्मणे।

रूपनामविभेदेन जगत्क्रीडति यो यतः॥

- Introduction: The Charge of Polytheism and the Problem of Conceptual Clarity

One of the most frequently raised objections against Hinduism is the claim that Hindus are polytheistic and therefore stand in opposition to so-called Semitic religions, which are often portrayed as strictly monotheistic traditions uniquely oriented toward salvation. Such assertions are commonly advanced without adequate philosophical engagement or conceptual precision. This article does not seek to refute the doctrines of any religious tradition. Its purpose is more restrained: to invite a slower, more reflective, and methodologically disciplined mode of thought. Firm rootedness in one’s own belief system is neither problematic nor undesirable; yet objections directed at other traditions without logical coherence or conceptual clarity ultimately weaken meaningful discourse.

It is often observed that reality resists confinement within rigid oppositions of black and white; between them lies a wide and meaningful grey. When this insight is applied to theology, monotheism emerges not as a single, uniform claim but as a spectrum of ways in which unity is conceived and articulated. It is within this intermediate space that the present discussion is situated. The aim is to show that, when examined philosophically, Sanātana Dharma articulates a vision of divine unity that is neither simplistic nor deficient. And in certain respects may even express a more rigorous understanding of monotheism than is commonly assumed.

- The Conceptual Origin and History of “Monotheism”

To approach this question responsibly, it is first necessary to examine the meaning and historical origin of the term monotheism. The word was coined in 1660 by Henry More, an English theologian and philosopher. Contrary to popular assumptions, the term does not occur in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, or the Qurān. Etymologically, it derives from monos (one), theos (god), and the suffix -ism (belief). Yet its philosophical function cannot be grasped through etymology alone.

For millennia, humanity lived without this category. Monotheism entered the English lexicon in a precise intellectual moment: Henry More’s An Explanation of the Grand Mystery of Godliness (1660), written amid political and theological instability in post–Civil War England.

1. The Seventeenth-Century Context of the Coinage

1.1 Restoration England and Intellectual Anxiety

The year 1660 marked the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II, following the English Civil War and Cromwell’s Interregnum. The intellectual climate was polarized between two perceived threats:

- Religious enthusiasm associated with Puritan claims of direct divine inspiration and blamed for political chaos.

- Atheism and materialism, especially the mechanical philosophy of thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, which appeared to dissolve the spiritual realm into matter and motion.

The Cambridge Platonists sought a rational middle path between fanaticism and reductionism.

1.2 Monotheism as a Philosophical Weapon

Henry More coined monotheism not as a neutral descriptor of ancient religions, but as a strategic concept defending what he regarded as rational religion. Even logical conviction in a single principle proves not enough unless that principle corresponds to the true God as defined within his Platonist-Christian framework.

Pantheism was explicitly rejected. To identify God with the world, More argued, was to abolish God altogether: “to make the World God is to make no God at all.” Pantheists were therefore denied the title of monotheists and effectively classed with atheists. Even Islam was accused of possessing a philosophically deficient and “hypocritical” monotheism.

From its inception, then, monotheism functioned as a normative and exclusionary concept, not a simple numerical claim.

1.3 The Cambridge Platonists and Rational Theology

Centered at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, figures such as More and Ralph Cudworth sought to revive a prisca theologia, a primordial rational wisdom they believed united Plato and Moses. The so-called reason, described as “the candle of the Lord,” was held to illuminate true religion.

Within this framework, monotheism named the “Grand Mystery of Godliness,” set against what they deemed superstitions, paganism, and materialist atheism. The term thus marked the boundaries of civilized and acceptable discourse about the divine.

2. The Evolution of “Monotheism” as a Category

As the Enlightenment advanced, monotheism gradually detached itself from the theological polemics in which it had been formed. With European expansion came an urge to classify the religions of the world, and the term shifted from a philosophical defense of rational religion to an anthropological category.

2.1. From Revelation to Psychology

David Hume’s The Natural History of Religion (1757) marked a decisive shift. Religion was explained not through revelation but through human psychology: fear, hope, and uncertainty. Although Hume allowed for movement between polytheism and monotheism, later thinkers would harden this fluidity into a rigid hierarchy.

2.2. Evolution and Religious Maturity

Nineteenth-century social evolutionism mapped religion onto a linear model of human progress. Monotheism came to represent intellectual maturity and rational adulthood, while polytheism was recast as an earlier, less developed stage. This framework closely mirrored Europe’s self-image as the apex of civilization.

2.3. Systematizing the Hierarchy

E. B. Tylor formalized this model by proposing a progression from animism to polytheism and finally to monotheism. Religious development was likened to political development: from tribes to kingdoms, from many spirits to a single supreme deity. Monotheism thus became the presumed endpoint of religious thought.

James Frazer extended this scheme by placing monotheism at the highest stage of religion, just before the rise of science. Many non-European practices, especially in India, were dismissed as “magic,” relegating them to the lowest rung of development.

2.4. Monotheism as a Civilizational Measure

By the late nineteenth century, monotheism had become a proxy for civilization itself. European Christianity occupied the summit, while polytheistic and animistic traditions were placed below. This hierarchy provided intellectual and moral justification for colonial rule.

2.5. The Colonial Application to India

Applied to India, this framework reduced Hindu diversity to idolatrous polytheism. Missionaries such as William Carey, William Ward, and Alexander Duff portrayed Hinduism not as a philosophical system but as a moral and intellectual deficiency to be corrected. The label “polytheism” thus functioned less as description than as judgment.

After examining the meaning and genealogy of the term monotheism, a natural question arises: why should Sanātana Dharma seek validation within a colonial category at all? The answer is clear and unapologetic. It does not. This discussion is not an attempt to compress an ancient and self sufficient metaphysical tradition into a framework produced by seventeenth century European theology and later reinforced by colonial anthropology. Rather, it is a deliberate engagement.

The exercise is undertaken to address critics in the very conceptual language they themselves employ. When claims are advanced through the category of monotheism, they must be examined on that ground, not because the ground is inherently authoritative, but because it is the basis upon which the critique is made. This is not capitulation, but clarification. It exposes how conclusions about Hinduism are frequently reached without logical rigor, without philosophical discipline, and without sustained engagement with its textual and metaphysical foundations.

Sanātana Dharma does not require external categories to legitimate its understanding of the Absolute. Yet when such categories are invoked carelessly, and applied without comprehension of either their own conceptual limits or the tradition being judged, it becomes necessary to respond with precision. The purpose, therefore, is not to seek inclusion within an imposed framework, but to demonstrate that conclusions formed without understanding are not reasoned judgments, but assertions lacking intellectual responsibility.

- An Introduction to the Adhikaraṇa Method for Theological Inquiry

Even after its invention, the term monotheism did not retain a fixed or stable meaning. As the preceding discussion has shown, its significance shifted across historical contexts, acquiring different shades as it moved from theological polemic to anthropological classification and finally to a civilizational marker. These were the historical transformations of the term. Its theological meanings, however, are far more complex and cannot be exhausted by historical analysis alone. A careful examination of these theological dimensions will be undertaken in the subsequent article, through a distinctive method of inquiry drawn from the Bhāratīya knowledge tradition, known as adhikaraṇa.

The Bhāratīya intellectual tradition offers a rigorous and methodical framework for examining philosophical and theological questions. This method, called adhikaraṇa, is most prominently employed in the sūtra literature, particularly in texts such as the Brahmasūtra and the Pūrvamīmāṃsāsūtra. These works address doubts that arise from the Vedic corpus and resolve them through tightly structured reasoning. Rather than presenting isolated assertions, they divide inquiry into well-defined units called adhikaraṇas, each designed to distinguish, examine, and adjudicate between competing viewpoints. This method is not confined to scriptural exegesis alone; it can be fruitfully applied to contemporary theological questions as well.

A classical verse outlines the formal structure of an adhikaraṇa:

विषयो विशयश्चैव पूर्वपक्षस्तदोत्तरम्।

सङ्गतिश्चेति पञ्चाङ्गं शास्त्रे अधिकरणं स्मृतम्॥

Viṣayo viśayaścaiva pūrvapakṣastadottaram ।

Saṅgatiśceti pañcāṅgaṃ śāstre adhikaraṇaṃ smṛtam ॥

According to this framework, every inquiry proceeds through five essential components, which together ensure clarity, rigor, and coherence in philosophical discussion.

1. Viṣaya (The subject)

Viṣaya refers to the clearly defined subject matter. Any meaningful inquiry must begin by establishing the precise topic under examination, which serves as the foundation for the entire discussion.

2. Viśaya (The doubt)

Viśaya denotes doubt. Wherever a subject is taken up for inquiry, doubt must naturally arise. Without doubt, discussion lacks depth and cannot proceed in an analytical or productive manner.

3. Pūrvapakṣa (The counter argument)

Pūrvapakṣa represents the preliminary or opposing position. A doubt must be articulated in its strongest possible form, ensuring that the challenge is neither caricatured nor weakened before being addressed.

4. Uttarapakṣa (The rebuttal)

Uttarapakṣa is the responding or establishing argument. Here, the opposing position is examined and resolved through careful reasoning, supported by logic and, where appropriate, authoritative textual evidence.

5. Saṅgati (The correlation)

Saṅgati signifies coherence and logical integration. The conclusions reached must align consistently with the subject, the doubt raised, and the arguments presented, forming a unified and internally consistent whole.

- Adhikaraṇa

The discussion proceeds in accordance with the classical adhikaraṇa method and is organized as follows.

1. Viṣaya (The Subject)

Here, the viṣaya, or subject of inquiry, is monotheism. Etymologically, it denotes belief in the existence of one God. However, this linguistic definition by itself does not resolve the philosophical complexity of the term. The nature of this oneness remains indeterminate. It is unclear whether it refers to numerical singularity, ontological unity, exclusive worship, supreme authority, or some combination of these. It is precisely this ambiguity and conceptual depth surrounding the idea of divine oneness that constitutes the central subject of the present discussion.

2. Viśaya (The Doubt)

Viśaya denotes doubt. The primary doubt addressed here arises from the frequently asserted claim that Hinduism is polytheistic. This doubt is generated by the visible plurality of deities, names, forms, symbols, and modes of worship within Hindu traditions. To an external observer, such diversity is often interpreted as belief in multiple independent gods, thereby placing Hinduism in opposition to traditions commonly labeled monotheistic. The doubt, therefore, is whether the presence of many deities necessarily entails polytheism, or whether such plurality can coexist with a deeper philosophical affirmation of divine unity. This question forms the immediate problem that demands examination.

3. Pūrvapakṣa and Uttarapakṣa (The Objection and the Response)

The pūrvapakṣa and uttarapakṣa will be presented in a dialogical manner. Objections arising from various Christian sectarian perspectives will first be articulated in their strongest possible form, without caricature or dilution. These positions will then be systematically examined and responded to from within the Hindu philosophical framework.

3.1 Śrī Madhvācārya vs. the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints

Hindu:

You accuse Hinduism of polytheism on account of its many deities. Yet your own theology speaks of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost as distinct divine realities. On what grounds, then, is Hindu plurality rejected while yours is defended?

LDS Interlocutor:

We do not worship multiple gods. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost are three distinct beings, yet they are perfectly united. Their unity lies in purpose. They are one in will, one in mind, and one in glory.

Hindu:

If they are physically distinct, occupying different locations and possessing separate bodies, in what sense does the term one God retain philosophical rigor. Unity of intention may explain harmony, but it does not establish ontological oneness.

LDS Interlocutor:

Monotheism does not require that only one divine being exist. It requires that there be one Godhead to whom worship and allegiance are owed. The Father alone is supreme, and worship is directed to Him in the name of the Son. This reflects the biblical pattern.

Hindu:

Then what you defend is not monotheism in the strict sense, but monolatry. Further, your rejection of creation out of nothing introduces an irreducible plurality. If matter and intelligence are co-eternal with God, then God is not the absolute ground of being, but one eternal reality among others.

LDS Interlocutor:

God is the organizer of eternal realities, not their creator from nothing. Matter is neither God nor created by Him. This preserves divine agency without collapsing God into the universe.

Hindu:

We too affirm a supreme God, worshipped alone, while acknowledging subordinate deities whose authority is derivative. Yet we do so without redefining unity as mere coordination. In the Tattvavāda of Śrī Madhvācārya, supremacy, dependence, and plurality are articulated with doctrinal precision. Hari alone is independent; all others subsist under His sovereignty and act by His will. Śrī Madhvācārya declares:

हरिर्हि सर्वदेवानां परमः पूर्णशक्तिमान्।

स्वतन्त्रोऽन्ये तद्वशा हि सर्वेऽते स जगद्गुरुः।।

ब्रह्मादयश्च तद्भक्त्या भागिनो भोगमोक्षयोः।

तस्माज्ज्ञेयश्च पूज्यश्च वन्द्यो ध्येयः सदा हरिः।।

(श्रीतन्त्रसारसंग्रहः १.७४,७५)[1]

Harirhi sarvadevānāṁ paramaḥ pūrṇaśaktimān

Svatantrō’nye tadvaśā hi sarve’te sa jagadguruḥ

Brahmādayaśca tadbhaktyā bhāgino bhogamokṣayoḥ

Tasmājjñeyaśca pūjyaśca vandyo dhyeyaḥ sadā Hariḥ

(Indeed, Hari alone is supreme among all deities, and omnipotent. He alone is independent; all others are dependent upon Him, and He is the almighty in the universe. Brahmā and the rest, through devotion to Him, partake in worldly enjoyment and liberation. Therefore, Hari alone is to be known, worshipped, revered, and meditated upon at all times.)

Here, plurality is neither denied nor confused with unity. Dependence is real, hierarchy is explicit, and supremacy is unambiguous. Worship is not dispersed, but ordered. The One is not preserved by abstraction, nor by a mere redefinition of allegiance. Unity cannot be secured by reducing oneness to conceptual formulas such as unity of purpose or unity of will, for such moves shift the question from ontology to language. Nor is monotheism sustained by restricting worship to a single figure while simultaneously admitting multiple independent divine beings, since allegiance concerns devotion rather than the metaphysical structure of reality itself. Genuine oneness is established only when all multiplicity is grounded in a single, sovereign, and self sufficient reality, from which all forms, powers, and agencies derive their being and authority.

This distinction becomes clearer when one considers the status of evil and opposition within the respective systems. In many strands of biblical theology, Satan appears as an independent adversarial agent who acts contrary to the will of God, introducing a real dualism within the moral and cosmic order. Such independence, even if qualified, weakens the claim of absolute sovereignty. By contrast, Hindu metaphysics does not admit an eternally autonomous principle of opposition. Even demons and adversarial beings function within the divine order and remain ontologically dependent upon the supreme reality. Their opposition is circumstantial and instrumental, not absolute, and their final liberation is not excluded in principle.

When plurality, including moral opposition, is thus understood as dependent and hierarchically ordered within a single all encompassing reality, the charge of polytheism loses its force. It does not withstand philosophical scrutiny, but dissolves once careful metaphysical distinctions are applied rather than defended through rhetorical reclassification.

…Continued in Part 2

[1] Śrī Madhvācārya, Śrī Sarvamūlagranthāḥ, Śrī Prajñānanidhi Tīrtha Svāmiji, Mulabagilu, 1998, 1037

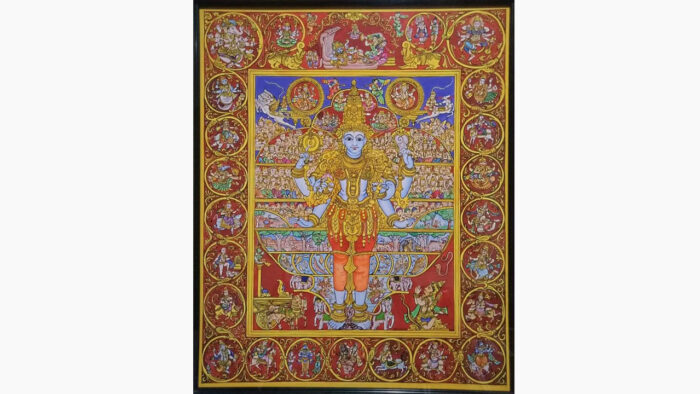

Feature Image Credit: pinterest.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.