Modern Science is often seen as the pinnacle of human rationality and progress. It is precise, logical and relentlessly empirical. It works through instruments and formulas, speaks in numbers, and examines only what can be tested. Yet beneath this polished surface lies something ancient: a forgotten root. This is the same deep impulse to know that Vedānta, the spiritual philosophy of the Upaniṣads, has been honored for millennia. In a way, modern science can be seen as Vedānta wearing a lab coat: exploring only a small tract of the vast landscape that Vedānta embraces in its entirety. While science charts the measurable and visible, Vedānta encompasses both the measured and the measurer, the known and the knower, as expressions of one indivisible reality.

If science is the art of knowing the seen, a journey that charts the patterns of matter, energy, and motion with remarkable precision, then Vedānta is the inquiry into the source of all knowing. It includes not only the world we observe (the seen), but also the one who observes (the seer), and the source from which both arise. This source, called Brahman, is not a deity, but pure, undivided awareness: consciousness itself. From it arises matter, all that is seen; mind, all that is thought; and energy, all that moves and transforms. Even the laws that govern them, our emotions, and the very curiosity that fuels science, are born of this source: Brahman, the undivided consciousness underlying all experience. Vedānta speaks of Ṛta, the cosmic order, not as a constructed theory but as the natural unfolding of Chaitanya — living, intelligent consciousness. In this vision, every sincere pursuit of truth, whether through meditation or microscope, reveals facets of a single, unified reality.

Ṛta, the cosmic order, is not an external framework imposed upon the universe, but the inherent rhythm through which reality expresses itself. It is not constructed but revealed: the natural articulation of Chaitanya, conscious being. The harmony found in physical laws, biological forms, and mental structures reflects not randomness, but intelligible coherence. This coherence, science measures through instruments and formulas; Vedānta measures through meticulous reasoning, metrics of inner experience, and disciplines like Jyotiṣa and Chandas. It recognises the cosmos not as engineered, but as self-revealing from within its own intelligent essence. The universe, then, is not a mechanism governed by blind rules, but a living field of order arising directly from awareness, Ṛta sustained by Chaitanya.

Science engages with the observable, the measurable, and the repeatable; and in doing so, it offers a powerful, yet bounded, view of reality. Its methods assume an intelligible cosmos, governed by consistent laws and accessible through reliable perception — assumptions that are not proven by science itself, but inherited from a deeper metaphysical intuition. Vedānta makes this intuition explicit. It does not dismiss science; rather, it reveals the very ground on which science stands. Perception, inference, doubt, and hypothesis — the tools of science — all arise within awareness. Vedānta studies not only the contents of consciousness but consciousness itself. In this vision, science is not negated but nested, a luminous branch of the greater tree of knowing. Honored in its place, science is not excluded but fulfilled.

While scientific materialism often regards consciousness as an emergent property of complex matter — a late arrival in a lifeless universe — Vedānta turns this view on its head. Consciousness is not produced by the brain, nor is it an epiphenomenon of neural activity. It is the very foundation of all experience — the unchanging witness in which all thoughts, sensations, and phenomena arise and dissolve. Vedānta thus sees consciousness not as a puzzle to be solved within material systems, but as the very ground from which all systems appear. It is not located somewhere in the universe; the universe is located in it. Matter, mind, and measurement appear within consciousness, not the other way around. The world does not give rise to consciousness; consciousness gives rise to the world. In this vision, consciousness is not located somewhere in the universe, but the illuminating presence without which nothing can be known, including science itself.

Quantum mechanics, with its observer-dependent outcomes, challenges the classical view of an objective, observer-independent reality. The act of measurement appears to collapse probabilities into facts, making the observer an inseparable part of the observed. This has baffled physicists for over a century. Vedānta, however, has never seen this as a conundrum. Long before wave functions and uncertainty, it declared that the conscious observer, the draṣṭā, is not a late-stage anomaly but the fundamental reality. The world appears to the observer, within the observer, and because of the observer. Rather than treating consciousness as a disruption to physical theory, Vedānta recognizes it as the sole light by which anything is known or knowable. Where quantum theory hesitates at the threshold of subjectivity, Vedānta steps through affirming the primacy of the knower over the known.

Science, in its rigor, insists that a claim must be falsifiable to be meaningful; that which cannot be tested or disproven lies outside its domain. This criterion, powerful within its scope, simultaneously marks the boundary of science itself. Vedānta does not resist this boundary; it simply points beyond it. Brahman, the infinite and unchanging reality, is not an object among other objects, subject to external observation or experimental refutation. It is the very subject, the Self (Ātman), through which all experience is known. Its certainty does not arise from deduction or instrumentation, but from direct, non-mediated realization (aparokṣānubhūti). Like the light that reveals all forms without being seen as a form itself, Brahman is self-evident. Science may describe the shadows on the wall with extraordinary precision, but Vedānta invites one to turn around and see the light itself.

Modern science, for all its precision, confines itself to what is observable, measurable, and falsifiable. Yet this very method rests on metaphysical assumptions it neither proves nor questions: that nature is orderly, that human perception is broadly trustworthy, and that the universe operates by consistent laws. These are not scientific conclusions, but foundational beliefs — silently inherited from the deeper intuitive certainty that Vedānta brings to light.

Vedānta does not reject science; it places it in context. It honors perception (pratyakṣa) and inference (anumāna), but also acknowledges a higher mode of knowing — direct, self-evident knowledge (śruti, ātma-jñāna). Brahman, the infinite substratum, is not an object to be disproved, but the very subject through which all experience becomes intelligible. Known not through inference but through direct realization (aparokṣānubhūti), Brahman is self-evident, like the light by which all things are seen, but which needs no other light to be seen itself.

In narrowing its scope, science gains precision but loses the whole. It refuses to speak of what cannot be tested — consciousness, purpose, Self, mokṣa. It explores the machinery of nature, not its source. In Vedāntic terms, this is buddhi functioning without awareness of ātman — brilliant, analytic, but fragmented. Vedānta invites a more complete seeing: not merely knowledge of things, but knowledge of the knower (jñāta). What science sets aside as untestable, Vedānta reveals as the only certainty. Brahman is not disproved, it is discovered, not as an object, but as the ever-present subject.

Vedānta is not content with intellectual explanation; its purpose is transformative. It begins with inquiry (jijñāsā), but ends in realization (jñāna). Its goal is not to believe in a higher power, but to awaken to the truth that one is not separate from it. Mokṣa is not salvation in the religious sense, but freedom from delusion — the dissolution of the false self in the light of the real. This is not abstraction but direct experience: the knower (jñātā), the known (jñeya), and the knowing (jñāna) are ultimately one. Vedānta, therefore, is not a system to be accepted, but a mirror that reveals what has always been true: tat tvam asi — “That thou art.”

Science walks with reason; Vedānta walks with insight. One dissects the leaf; the other tastes its life. One maps the wave; the other knows it is water. They do not oppose — they complete. So when we say, “Science is Vedānta wearing a lab coat,” we mean that science is a partial expression of the same universal urge to know. But in roaming only where light already shines, it forgets its own source — the Self — and avoids the Chaitanya from which even reason arises. The lab coat and the robe need not stand apart. When precision is joined with presence, when inquiry bows to insight, knowledge becomes whole. Science reveals the how; Vedānta reveals the how and the who. To know both is to walk with eyes open — outward and inward — and see the cosmos not as separate, but as Self.

The question is not whether science or Vedānta is right. The question is whether we are ready to look beyond surfaces and see what is always present — awareness itself, which wears all names, and wears none. To reunite science with Vedānta is not to discard the lab coat, but to return it to its source — the robe of pure inquiry. For science, too, is born of the human longing to know. But in naming the stars and measuring the cells, it often forgets the light by which it sees. Let it continue — boldly, brilliantly — but also inwardly. Only when outer clarity meets inner stillness does true knowledge arise. Not just vijñāna, analytical knowing — but jñāna, the silent recognition: I am That (Aham Brahmāsmi).

References

- Upaniṣads (especially the Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, and Taittirīya Upaniṣads)

– Primary source of Vedāntic inquiry into Self (Ātman), consciousness (Chaitanya), and non-duality (Advaita). - Śaṅkara’s Commentary on the Brahma Sūtras (Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣya)

– Foundational Advaita Vedānta interpretation; articulates non-duality and the limits of conceptual knowledge. - Swami Vivekananda – Jnana Yoga

– Modern, accessible presentation of Vedāntic ideas, including their intersection with rationality and science. - Sri Aurobindo – The Life Divine

– Explores consciousness, evolution, and spiritual realization with synthesis of science and Vedānta.

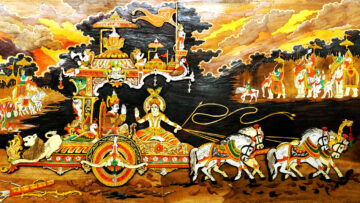

Feature Image Credit: x.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.