It is commonly claimed by many scholars that after overthrowing and assassinating the last Mauryan emperor Bṛhadratha, Puṣyamitra Śuṅga, the Brāhmaṇa Senāpati (commander-in-chief) went on to brutally purge Buddhist clergy and monuments, from Pāṭaliputra to as far as Sialkot, and that his anti-Buddhist rhetoric and violence probably stemmed from his Brāhmaṇical identity, which caused Buddhism to shift and evolve under Hellenic influence in Gandhāra. But, is it all false, or some kernel of truth exists in such claims?

Assassination of Bṛhadratha: A Game of Shadows

Bṛhadratha Maurya (c. 187-85 BCE) came from an illustrious line of rulers, eulogically hailed as the first imperial dynasty of India (Mookerji 1943, pg. 1), with the list of rulers including Chandragupta Maurya and Aśoka. However, after Aśoka, the fortunes of the Mauryan empire went on to witness a steady and systemic decline. As the empire fractured from within, and faced a stirring array of invasions from north-west, dissensions became a rule rather than an exception. On the ascension of Bṛhadratha (c. 188-87 BCE), the mighty Mauryan empire bore little semblance to its glorious heydays, and had only retained its footprint in Magadha (Raychaudhuri 1972, pg. 102). Faced with an imminent existential crisis, Puṣyamitra Śuṅga, the commander-in-chief of Mauryan military, assassinated Bṛhadratha while the latter was undertaking a routine inspection of the standing army. R.C. Majumdar (1951, pg. 94-96) describes the event in the following manner-

“We owe to Bāṇa’s Harṣacharita some details of the story of the overthrow of the Maurya power by Puṣyamitra. Bāṇabhaṭṭa, who flourished eight centuries after the event, relates how Puṣyamitra, the Senāpati or Commander-in-Chief, assembled the entire Maurya imperial army, evidently on the pretext that he was anxious that his sovereign should see for himself with his own eyes what a fine fighting force he could put into the field of battle, and then assassinated him at the military parade and review. This incident shows that already Puṣyamitra was carefully preparing the ground for his coup d’état by seducing his army from its loyalty to the Maurya king.”

Why Puṣyamitra took this extreme step, is hitherto not unanimously agreed upon by scholars. Some attribute it to the administrative weakness of Bṛhadratha, growing aspirations of Puṣyamitra, or the attempt of Puṣyamitra to safeguard the last frontier against the invasion of Yavaṇas, led by King Dhammamita[=Demetrius I ?], as the Yuga Purāṇa tells us-

- Then, having approached Saketa, together with the Pānchāla and Mathura, the Yavanas (Indo-Greeks), wicked and valiant, will reach Kusumadhvaja (“The city of the flower-standard”, Pāṭaliputra).

- Then, once Puṣpa-pura (Pāṭaliputra) has been reached, [and] its celebrated mud[-walls] cast down, all the realms will be in disorder, there is no doubt.

- There will then finally be a great war, of wooden weapons, and there will be the vilest of men, dishonorable and unrighteous.

That the nascent Śuṅga state had to combat the Yavaṇas is further known from Mālavikāgnimitram of Kālidāsa (Mirashi & Navalekar 1969, pg. 44). The complexity of the situation gets further compounded when Sri Lankan texts like Paramparā-pustaka highlight the fondness of marital relations between the Mauryas and the Greeks, a fact also affirmed by Greek architectural influence in Mauryan Art (Gupta 2002, pg. 19-21).

This prompted H.P. Shastri (1910) to present Puṣyamitra as the defender of orthodox Indic traditions, which had been oppressively sidelined earlier by Mauryan kings, especially Aśoka (Olivelle 2023, pg. 227) who not only sponsored alien customs, but heavily patronized Buddhism, a religion that helped them move beyond the orthodoxy of Brāhmaṇic ritual-order. This same approach was picked up by V.A. Smith (1924, pg. 213), who asserted-

“Puṣyamitra was not content with the peaceful revival of Hindu 17 rites, but indulged in savage persecution of Buddhism, burning monasteries and slaying monks from Magadha to Jalandhara, in the Punjab. Many monks who escaped his sword are said to have fled into the territories of other rulers.”

To this, historic sanctitude was later accorded by P.G. Bagchi and N.N. Ghosh. Here, we witness the supposedly pro-Brāhmaṇa and anti-Buddhist rhetoric that has both defined, and equally marred the historic reputation of Puṣyamitra. But, does the evidence stand scrutiny?

Puṣyamitra: pro-Brāhmaṇa and anti-Buddhist?

The anti-Buddhist narrative surrounding Puṣyamitra is strongly linked to his perceivable Brāhmaṇic origin, and their historic mis-treatment by Aśoka. While it is true that most Brāhmaṇas opposed the philosophical innovations and their stringent implementation by Mauryan machinery (Olivelle 2023, pg. 169), this does not count as oppression. More interesting, however, is the fact that historians are not sure whether Puṣyamitra was himself a Brāhmaṇa or not! Bāṇabhaṭṭa in Harṣacharita addresses him as Anārya (non-Ārya)-

Senānīr anāryo mauyaṁ vṛhadrathaṁ pipeṣa puṣpamitraḥ svāminam.

(The non-Ārya general Puṣyamitra slew his Maurya master Bṛhadratha while inspecting (reviewing) the army.)

With Brāhmaṇical outburst somewhat calmed, we may now proceed to hear Buddhist outcries, which come from Divyāvadāna, Manju-Śrī-Mūla-kalpa (henceforth MSMK), and Tārānātha’s history of Buddhism. What we encounter here are incoherent storylines, veiled references, and mind-blowing confusion. Divyāvadāna makes Puṣyamitra a Maurya prince! That Puṣyamitra, in his hatred of Śramaṇas (i.e. Buddhist monks), went as far as Sialkot literally flies in the face of truth, as the same city was the capital of Menander (c. 165-130 BCE), a known patron of Buddhism. P.G. Bagchi, vide Jayaswal (1933, pg. 38-39) uses MSMK to make one Gomimukhya bear equivalence to Puṣyamitra; while Gulma was indeed a military unit, making Puṣyamitra its head would be a great disservice to his Senāpati status, which he certainly did have, as inscriptions also speak of it (Sahni, EI XX, pg. 54-58). Definitely stranger things happened with Ghosh, who christened Puṣyamitra as an anti-Buddhist by citing a passage of Tārānātha where the latter actually made Bhikṣus (monks), rather than Puṣyamitra, the primary accused for burning temples and monasteries from Jalandhara to Magadha!

Conclusion: Puṣyamitra exonerated?

When the evidence is examined with patience, the anti-Buddhist accusations against Puṣyamitra vanquish into thin air. While it is certainly true that Puṣyamitra did not patronize Buddhism as a state-religion like the Mauryas, it does not turn his reign into a vicious monstrosity. Similarly, organizing an Aśvamedha sacrifice should not be considered as a ritualistic affirmation of Brāhmaṇism, but rather an attempt to proclaim his newfound sovereignty. With his Brāhmaṇic genesis not beyond suspicion, one also cannot view his actions as an attempt revive Brāhmaṇism (Raychaudhuri 1972, p. 389).

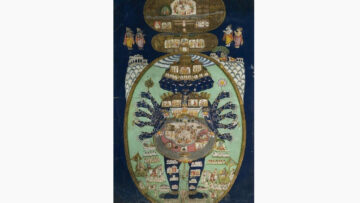

However, whence we move from the epoch of Mauryas to that of the Śuṅgas, an unignorable change occurs in art and craft. N.R. Ray, foremost scholar of ancient Indian Art, succinctly describes this difference in a Buddhist context in the following way-

“The art of Maurya period was essentially a dignified and aristocratic court art, in which animals figured prominently. This form of art — mostly sculptures (from mainly palaces and cities of Pāṭaliputra) — were produced during the period of the Mauryan… Śuṅga is thus the first organized and integrated art activity of the Indian people as a whole and stands directly counter-posed to the court-art of the Mauryas. It reflects for the first time results of the ethnic, social and religious fusion and integration that had been evolved through centuries on the Indian soil, more particularly in the Madhyadeśa.”

It must also be noted that the increasingly localized Śuṅga Art, rather than isolating Buddhism, helped it develop links with folklore and other un-Hinduized traditions, especially with the Nāga and Yakṣa cults, which prominently occur in narrative friezes of the Bharhut Stūpa, built during the ‘ruling years of the Śuṅgas’ (Sungnāma Rāje); while this does not directly prescribe Buddhist inclination to Puṣyamitra, it also does not indirectly accuse him of a ‘Buddhist purge’. Scholars suspect that the construction of some of the post-Mauryan wooden railings at Bodh Gaya was sponsored by the Śuṅgas. Moreover, that the Śuṅgas did not discriminate against Buddhism is well confirmed by the presence Paṇḍita Kauśika, a Buddhist and Parivrājaka, in court of Puṣyamitra. Nāgasēna, author of Milinda Pāño, locates the residence of the venerable Buddhist Āchārya Dharmarakṣita in a garden of Pāṭaliputra, which would be hard to think of had Puṣyamitra been a tyrannically anti-Buddhist king.

Thus, in the final analysis, the charge of Buddhist persecution upon Puṣyamitra after overthrowing Mauryas and assuming imperial office, stands proven false.

References

Bagchi, P.G. (1929). On some Tantric texts studied in Ancient Kambuja. Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol. 5, p. 398.

Cowell, E.B. and Thomas, F.W. (1897). The Harṣacharita of Bāṇabhaṭṭa, an English translation. London: Royal Asiatic Society. https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/the-harsha-charita/d/doc116135.html

Ghosh, N.N. (1943). Did Puṣyamitra persecute the buddhists?. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 6, pp. 109-116.

Gupta, S.P. (2002). Ancient Indian Art, Architecture and Iconography. New Delhi: Dk Print World Ltd.

Jayaswal, K.P. (1933). An Imperial History of India. Lahore: Motilal Banarsidass.

Majumdar, R.C. (1951). The Age of Imperial Unity. History & Culture of Indian People, Vol. 2. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.544243/page/96/mode/1up

Mirashi, V.V. and Navalekar, N.R. (1969). The Age of Kālidāsa: Date, life and works. Poona: Oriental Book Agency.

Mitchiner, John E. (1986). The Yuga Purāṇa, English translation. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, Bengal. https://archive.org/details/TheYugaPurana/The%20Yuga%20Purana?view=theater#page/n73

Mookerji, R.K. (1943). Chandragupta Maurya and his times. Sir William Meyer Lectures, 1940-41. Madras: University of Madras. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.281321/page/n14/mode/1up.

Olivelle, Patrick. (2023). Ashoka: Portraits of a philosopher king. New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India.

Ray, N.R. (1945). Maurya and Śuṅga Art. Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.28966/page/n92/mode/1up

Raychaudhuri, H.C. (1972). Political History of Ancient India: from the ascension of King Parīkṣita to the fall of the Gupta Empire, 6th Edition. Calcutta: University of Calcutta Press. https://archive.org/details/dli.calcutta.11121/page/326/mode/1up

Sahni, Rai Bahadur D.R. (1930). A Śuṅga inscription from Ayodhyā. Epigraphica Indica, Vol. XX, pp. 54-58.

Shastri, H.P. (1910). A Short History of India. Collingwood: Trieste Publishing Pty Ltd (Rpt. 2017).

Smith, V.A. (1923). A History of India, 4th Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.12667/page/213/mode/1up.

Feature Image Credit: A masculine figure from Śuṅga period, c. 2nd-1st Century BCE, Guimet Museum.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.