A Reflection on Experience, Response and Inner Freedom

Prologue

Why does life unfold through sensations we never choose, yet feel deeply responsible for, as if we authored every pleasure and pain, and must learn through living where experience ends and our true responsibility quietly begins?

There are moments when life touches us before we are ready. A sharp word lands. A sudden warmth spreads through the body. A memory rises without warning. In those moments, nothing feels chosen. Experience simply arrives. Yet soon after, something else happens inside us. A thought forms. A reaction stirs. A story begins to take shape. This quiet movement between what happens and how we meet it often goes unnoticed. The Bhagavad Gītā invites us to pause here. It asks us to look closely at this space. Not to fix anything. Only to see more clearly where life acts, and where we are asked to act.

This reflection begins from that pause.

Introduction: The Question of Authorship

A moment arrives. The body tightens. The heart lifts or sinks. Before any thought forms, something is already happening inside. Pleasure appears without invitation. Pain follows without warning. Heat, cold, comfort, and discomfort pass through the senses as part of ordinary living. We do not choose these arrivals. Yet they feel deeply personal.

This is where confusion quietly begins. Experience shows up on its own. The body tightens or relaxes, and we immediately feel responsible for what has already happened. A sharp word hurts. Praise pleases. A sudden sound startles. In each case, sensation reaches us first. Thought comes later. Responsibility, however, is felt immediately. We wonder what this means about our place in life.

Bhagavad Gītā Verse 2.14 quietly turns our attention to this question (BG 2.14).

मात्रास्पर्शास्तु कौन्तेय शीतोष्णसुखदुःखदाः ।

आगमापायिनोऽनित्यास्तांस्तितिक्षस्व भारत ॥ BG २.१४ ॥

mātrāsparśāstu kauntēya śītōṣṇasukhaduḥkhadāḥ |

āgamāpāyinō:’nityāstāṁstitikṣasva bhārata || BG 2.14 ||

(O Arjun, sensations of pleasure and pain, heat and cold arise from the contact of senses with their objects. These feelings are temporary; they come and go. Learn to tolerate them.)

Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa speaks to Arjun about sensations that arise from contact and then pass away (BG 2.14). Heat and cold are named. Pleasure and pain are named. None of them are judged. None of them are explained away. They are simply described as movements that come and go.

This is a turning point because it changes where we place our attention. Many people spend life trying to control what is felt. We chase what feels good. We try to avoid what feels bad. We build schedules, habits, and relationships around this pursuit. Still, sensation keeps arriving in ways we cannot fully predict. Even the most careful life meets sudden discomfort. Even a difficult day holds a small, pleasant moment that we did not plan. The verse is not trying to make us passive. It is inviting us to see the nature of sensation as it is.

Here, a simple question opens. Sensation is not authored by us. Responsibility appears in how we respond. These are two different movements. When they are blended together, life feels heavy and confusing. When they are seen separately, something begins to loosen.

Experiences arrive without permission. That much is clear. Still, life does not feel random. Our days carry direction. Our actions leave traces. Relationships grow or strain based on what we do next. This creates the central inquiry of this article. If we do not author what appears, where does authorship actually live?

This reflection does not aim to escape experience. It does not ask for detachment from life. It asks for clarity about where effort is meaningful. It asks where freedom begins when control was never present to begin with.

The purpose of this article is to explore this question patiently. It looks at how experience arises, how response takes shape, and how inner freedom grows through understanding. Along the way, it draws from the Bhagavad Gītā, lived psychology, and simple observation. The inquiry begins here, not with answers, but with careful attention.

As we move forward, the next step is to place this verse more fully in its original setting. Understanding Arjun’s state helps us understand why this teaching matters, and why it continues to speak so directly to human life today.

Context from the Gītā

To feel the weight of Bhagavad Gītā Verse 2.14, it helps to remember where Arjun stands when he hears it. He is not calm. He is not reflective in a quiet room. He is standing on the battlefield, surrounded by faces he knows, roles he carries, and consequences he cannot escape.

Arjun is a warrior prince in the Mahābhārata war, facing his own family and teachers across the battlefield, and the Gītā unfolds as a dialogue where he turns to Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa for guidance at the moment his inner strength collapses.

His body is tense. His mind is crowded. His will feels fractured. Earlier verses have already shown his grief, trembling, and confusion (BG 1.28–1.47). By the time this teaching arrives, Arjun is overwhelmed by what he feels inside.

Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa begins His response not by solving the war, but by addressing experience itself. He speaks of mātrā-sparśa (sense contact). This phrase points to something very basic. The senses touch the world, and experience arises. Skin meets temperature. Ears meet sound. Eyes meet form. From this meeting, pleasure and pain are born. The verse does not describe these sensations as personal achievements or personal failures. They are outcomes of contact. They arise because a living being has senses and a world to meet.

This framing matters deeply. Arjun is drowning in emotion, yet Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa does not tell him that his pain is wrong. He also does not glorify it. He places it in the natural order of embodied life. Pleasure and pain are presented as results, not verdicts. They are not signs of virtue or weakness. They are signals that contact has occurred. This shifts the tone of the entire dialogue. Arjun is not being judged for feeling what he feels. He is being guided to understand what feeling is.

The verse then introduces a rhythm that quietly changes everything. These sensations are āgama-apāyinah (arriving and departing). They come. They stay for a while. They leave. Heat gives way to coolness. Pain softens. Pleasure fades. This movement is not random. It is the natural flow of experience. By naming this rhythm, Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa invites Arjun to step back just enough to see the pattern rather than drown in the moment.

For someone in distress, this reminder is grounding. It does not deny suffering. It places suffering in time. It says that what is felt now is not the whole story. It is a moment in motion. This insight begins to loosen Arjun’s grip on the belief that his present pain defines his entire reality.

Then comes the central instruction of the verse. Tāṁs titikṣasva. Practice titikṣā (forbearance). This word does not mean suppression. It does not mean forcing oneself to feel nothing. It points to the capacity to stay present without collapsing inward or acting blindly outward. Titikṣā is steadiness in the presence of movement. It is the strength to allow sensations to pass without surrendering one’s inner balance.

Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa offers this instruction early in the teaching for a reason. Before Arjun can understand duty, knowledge, or devotion, he must learn to stay with experience without being ruled by it. The battlefield demands action. Yet action that arises from unchecked reaction only deepens confusion. Titikṣā creates the inner space where clarity can later emerge.

Seen in this light, Verse 2.14 is not a minor observation about discomfort. It is a foundational lesson. It trains Arjun to recognize experience as experience. It trains him to see sensation as movement rather than command. This prepares him to listen, to discern, and eventually to act with responsibility.

As we move forward, this context helps us see why the question of authorship arises so naturally here. If sensations arrive and depart on their own, then authorship must lie elsewhere. The next section turns directly to this insight and explores what it means to experience life without claiming ownership over every sensation that appears.

Experience Without Authorship

There is a quiet honesty in noticing how experience actually begins. A sound is heard before you decide to listen. A sensation of hunger appears before you think about food. A feeling of irritation rises before you name it. These moments reveal something simple. Experience does not wait for intention. It arrives first. Only later does the mind step in to explain, justify, or resist what has already happened.

This is not something hidden or rare. It happens throughout the day. You feel the chair beneath you. You notice the weight of the body. You sense warmth, pressure, or fatigue. None of this asks for approval. Sensory events unfold as part of being alive. They arise from contact. The senses meet the world, and experience takes shape. In this sense, life presents events. It does not seek permission.

When we slow down enough to see this, a useful distinction becomes clear. There is a difference between what happens and how we respond. What happens is immediate. It is fast. It belongs to the body and the sensory system. Response unfolds a moment later. It carries thought, memory, and habit. It carries interpretation. This space between happening and responding is small, yet it holds great significance.

Most of our struggle comes from collapsing these two into one. We feel pain and say I am hurt. We feel pleasure and say I need more. The experience arrives, and the story follows so closely that they feel inseparable. Yet with gentle attention, they can be seen as distinct movements. Sensation arises. Awareness notices. Response forms.

The Bhagavad Gītā quietly points to this distinction by naming sensations as mātrā-sparśa (sense contact) and by reminding us that they are āgama-apāyinah (arriving and departing) (BG 2.14). This language loosens the sense of ownership we place on experience. If sensations arrive and depart on their own, then they are events. They are movements in life. They are not declarations about who we are.

At this point, attention begins to turn inward in a different way. Instead of asking why this happened to me, a softer question appears. What is it that notices this happening? This shift does not deny experience. It deepens relationship with it. Sensations still arise. Thoughts still appear. Emotions still move. Yet something steady is now being sensed beneath them.

This prepares the ground for a deeper understanding spoken of in the Gītā. Prakṛiti (nature) refers to the field in which all experience unfolds. It includes the body, the senses, the mind, and the play of sensations. It is active. It moves. It changes. Within this field, experiences arise according to contact and conditions. Puruṣa (pure consciousness) refers to that which notices this movement. It does not push experience into being. It does not block it either. It simply witnesses.

This distinction is not meant to be a philosophical decoration. It helps clarify authorship. If Prakṛiti presents experience, then authorship does not lie at the level of sensation. If Puruṣa witnesses, then authorship does not lie in observation alone. The question then becomes practical. Where does responsibility live if experience arises on its own and awareness simply notices?

The answer begins to form when we see that response is shaped in awareness. Response carries choice. It carries discernment. It carries the possibility of steadiness. This is why the Gītā places so much emphasis on how one meets experience, rather than on controlling what appears. Experience moves. Awareness remains present. Response shapes direction.

As this understanding settles, the inquiry into authorship becomes clearer. Life brings events. Sensation does its work. Awareness notices. Then response enters. This is where the pen is placed in our hand. The next section explores this more fully by looking at response as responsibility, and by reflecting on how inner steadiness begins to shape the path we walk.

Response as Responsibility

Once it becomes clear that sensation arises before choice, responsibility finds a new place to stand. It no longer sits at the moment experience appears. It begins just after. Sensation has already arrived. The body has already registered heat, pain, pleasure, or tension. What follows is where responsibility quietly enters.

This is where the Bhagavad Gītā places its emphasis. Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa does not ask Arjun to prevent sensation. He asks him to meet it with steadiness. The instruction tāṁs titikṣasva points to this shift (BG 2.14). Titikṣā (forbearance) is not emotional control. It does not demand suppression. It invites the capacity to remain present when experience is uncomfortable, and to remain balanced when experience is pleasant.

Reaction is quick. It rises from habit and conditioning. When pain appears, reaction often pushes away. When pleasure appears, reaction often grasps. These movements happen fast, sometimes before awareness catches up. Reaction narrows attention. It pulls the mind into urgency. Over time, this creates suffering because life begins to feel like a series of pressures that must be managed.

Response is different. Response takes place in awareness. It allows sensation to be felt without being turned into a command. Pain can be acknowledged without becoming a story of injustice. Pleasure can be enjoyed without becoming a demand for repetition. This small shift creates space inside. In that space, the nervous system settles. The mind regains perspective. Action becomes measured rather than driven.

This is why the Gītā treats titikṣā as a strength. It is not passive endurance. It is an active steadiness that holds experience without collapsing into it. Titikṣā allows a person to stay rooted while the surface of life moves. It makes it possible to remain ethical when emotions run high. It makes it possible to act with care when the body feels pressured.

Responsibility, in this light, is not about controlling outcomes. It is about shaping direction. One cannot author the arrival of heat or cold. One cannot author the sudden rise of emotion. Yet one can author the tone of the response. One can choose whether reaction hardens into harm or softens into understanding. Over time, these choices shape character.

Maturity grows here. Discernment deepens here. Ethical living begins here. A person who responds rather than reacts is not detached from life. Such a person is deeply engaged, yet not thrown off balance by every passing state. This steadiness allows values to guide action rather than impulse.

Seen this way, responsibility becomes gentle and demanding at the same time. It does not ask for impossible control. It asks for presence. It asks for honesty about what is felt. It asks for patience with oneself. This form of responsibility is sustainable because it works with life as it is.

As this understanding settles, authorship starts to feel less like control and more like participation. Life continues to present events. Sensations continue to arise. Within this flow, the quality of response quietly influences how life unfolds. This prepares us to ask the next question more clearly. If response carries authorship, then who or what responds? The next section turns to Vedāntic insight to explore this question at a deeper level.

Who Is the Author Then? Vedāntic Insight

As the question deepens, Vedāntic insight offers a careful way to place authorship without confusion. It does not rush to assign blame or control. It first asks us to see clearly how experience itself is structured.

Vedānta speaks of Prakṛiti (nature) as the field in which all sensations, emotions, and mental movements arise. This field includes the body, the senses, the nervous system, and the flow of thoughts and feelings. Prakṛiti is active by design. It moves according to causes and conditions that are already in place. Heat, cold, pleasure, fatigue, restlessness, and calm all arise here. None of these wait for permission. They unfold as part of nature’s rhythm.

Alongside this field is Puruṣa (pure consciousness). Puruṣa does not act within experience. It does not produce sensation or suppress it. It is the presence by which experience is known. Whether the body is at ease or under strain, whether the mind is clear or crowded, Puruṣa remains as the witness. It allows experience to appear without becoming altered by it.

This distinction is essential. If Prakṛiti presents experience and Puruṣa witnesses it, then authorship cannot belong to sensation. Sensation arises from contact within nature. It also cannot belong to witnessing alone because witnessing does not initiate action. Vedānta therefore points to a subtler place where responsibility appears.

Within Prakṛiti operate the guṇas (qualities of nature). These guṇas shape how experience is felt and how tendencies form. Sattva (clarity and harmony) brings balance, understanding, and steadiness. Rajas (restless drive) brings movement, urgency, and desire. Tamas (inertia) brings heaviness, dullness, and resistance. These qualities are not chosen in the moment. They are conditions that influence mood, perception, and impulse.

At different times, different guṇas become prominent. A settled mind reflects Sattva. Pressure and ambition stir Rajas. Exhaustion invites Tamas. These shifts happen naturally. They color experience and push behavior in certain directions. Yet they do not determine a life on their own.

Vedānta names the unconscious claiming of these movements as kartṛitva-bhāva (sense of doership). This is the habit of assuming authorship over actions and reactions that actually arise from Prakṛiti (nature). When this habit operates unseen, impulse feels personal and unavoidable. Responsibility feels heavy and confused.

In Vedāntic terms, this persistence of doership is explained through adhyāsa (superimposition), where the movements of Prakṛiti (nature) are mistakenly overlaid upon Puruṣa (pure consciousness), allowing action and reaction to feel personally authored.

Authorship begins to shift when awareness recognizes this pattern. Puruṣa (pure consciousness) notices the play of the guṇas without being pulled blindly by them. In that noticing, response becomes possible. One may feel restlessness without being driven by it. One may feel heaviness without surrendering to it. One may feel clarity and allow it to guide action.

Here, responsibility finds its proper place. It does not lie in stopping sensation. It does not lie in denying impulse. It lies in discerned response. Response shaped by awareness does not fight nature. It understands nature and acts within it wisely.

Seen this way, authorship is quiet and grounded. Life continues to move through Prakṛiti. Awareness continues to witness through Puruṣa. Within this living flow, response informed by discernment shapes direction. This is not control. It is participation rooted in understanding.

When this insight settles, self-judgment softens. Feelings are no longer treated as failures. Sensations are no longer treated as commands. Responsibility becomes clear and humane. One responds, not as the maker of experience, but as the steward of direction.

With this Vedāntic clarity in place, the inquiry naturally turns toward the body and brain that live this process every day. The next section looks at how modern neuroscience describes this same movement of sensation, reaction, and response in its own language.

Brain Research Perspective: Sensation, Reaction, and Choice

Modern brain research offers a useful mirror to what the Gītā describes from lived experience. Sensory contact reaches the brain through the thalamus (the brain’s central relay station that filters and directs sensory information). This process is fast. It happens before reflection. The body knows heat, sound, or pressure almost instantly.

Emotional charge often follows through the amygdala (the brain’s alarm for fear and anger). When sensation carries threat or intensity, this system activates quickly, preparing the body to react (LeDoux, 1996). At this stage, there is urgency but little clarity.

As the mind begins to interpret what is happening, the default mode network (the brain’s self-story and daydream network) weaves meaning around the experience. It explains, judges, and personalizes what has already occurred (Raichle et al., 2001).

Conscious response depends on the prefrontal cortex (the brain’s manager for planning, focus, and self-control). This region supports regulation, pause, and choice, yet it requires steadiness and training to stay engaged under pressure (Gross & John, 2003; Tang et al., 2015).

The key insight aligns closely with BG 2.14. Experience arises quickly. Response matures slowly. Inner freedom grows as this capacity is strengthened.

(Source:

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362.

- LeDoux, J. E. (1996). The emotional brain. Simon & Schuster.

- Raichle, M. E., et al. (2001). A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(2), 676–682.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225.)

Application in Life’s Context

The truth described so far is not meant to stay in thought alone. It meets us in small moments across the day. A sudden noise startles the body. A message on the phone brings relief or unease. Fatigue sets in without asking. These are unchosen experiences. They arrive as part of living in the world. What follows them shapes how a day unfolds and, over time, how a life takes form.

For a student, this shows up as pressure and comparison. The classroom and the screen are full of signals. Grades, expectations, and future plans press in through the senses. A remark from a teacher or a peer can trigger tension before thought has time to intervene. The body tightens. The mind rushes ahead. If reaction takes over, anxiety grows and attention scatters. When response is practiced, the same pressure can be met with steadiness. Sensation is acknowledged. Breath returns. Focus is reclaimed. Learning becomes possible again.

In family life, unchosen experience often arrives through emotion. A familiar tone can stir irritation. A loved one’s silence can awaken worry. Old patterns surface without invitation. These moments feel personal because history is involved. Yet the first wave is still sensation and feeling arising in Prakṛiti (nature). When reaction dominates, words spill out that deepen distance. When response is present, a pause opens. One listens more fully. One speaks with care. Relationship begins to heal in that space.

Professional life carries its own forms of sensory and emotional contact. Praise can lift the chest. Criticism can sting sharply. Deadlines create bodily urgency. Ambition fuels restless drive. None of these arise by choice. They come with roles and environments. Reaction often pushes one to overwork, withdraw, or compete blindly. Response allows discernment. Effort is given without burning out. Feedback is received without collapse. Action aligns with values rather than impulse.

Across all these contexts, the same pattern repeats. Experience arrives. The body responds first. The mind follows. Between sensation and action lies a narrow opening. This opening is where responsibility lives. It is not always easy to access. It grows through practice and patience. Each time one notices a reaction forming and chooses to pause, that opening widens.

Inner life becomes the training ground for this shift. Simple moments of noticing breath, posture, and feeling strengthen awareness. Sensations are felt without immediate judgment. Thoughts are seen without being chased. Over time, this builds the capacity to remain present when life moves quickly. This is where titikṣā (forbearance) becomes lived rather than conceptual.

As this way of living takes shape, authorship feels less heavy. One no longer feels responsible for every feeling. Responsibility rests in how one meets what arises. This brings relief and dignity at the same time. Life continues to present events. Response continues to shape direction.

As these life’s contexts settle in the mind, the question of authorship becomes less abstract. It feels lived. The next section draws these strands together and reflects on how reaction gives way to response as a steady way of being, shaping life from within rather than being pushed from outside.

Seen this way, the ordinary pressures of study, family, work, and inner life become living expressions of Śhrī Kṛiṣhṇa’s reminder that sensations arise through contact and pass away, while steadiness in response remains our true work (BG 2.14).

Integration: From Reaction to Response

As the reflections come together, something simple becomes clear. Life does not pause for understanding. Sensations continue to arise. Emotions continue to move. Thoughts continue to form. This movement belongs to living itself.

What changes is not the flow of experience. What changes is how it is met. Awareness begins to stay present instead of being pulled immediately. Breath is noticed, and the body no longer rushes forward. In that pause, choice becomes possible.

This is where authorship finds a grounded meaning. It is not about control. It is about participation. Life brings what it brings. The body feels. The mind reacts. Awareness notices. Within this noticing, response begins to take shape.

Experience moves through Prakṛiti (nature). It follows rhythms that are not personal. Sensations rise and fall. Moods shift. Circumstances change. Awareness remains present through these changes as Puruṣa (pure consciousness). It does not interfere. It illuminates what is happening.

When this distinction is lived, effort becomes more precise. Energy is no longer spent trying to stop experience. Attention turns toward how experience is carried. Reaction tightens the system. Response softens it. This difference is felt directly in the body and mind.

Psychological practice supports this movement. When attention is trained to pause, habits lose some of their grip. Emotional surges are noticed earlier. Thoughts are seen before they harden into action. This does not remove difficulty. It changes the relationship with difficulty.

Vedāntic insight offers the same orientation in a quieter language. Sensation belongs to Prakṛiti. Witnessing belongs to Puruṣa. Responsibility appears when awareness meets impulse with discernment. This meeting is not dramatic. It is steady. It grows through repetition.

Titikṣā (forbearance) becomes central here. It allows experience to pass through without being turned into urgency. Discomfort is felt without collapse. Pleasure is enjoyed without clinging. This steadiness reshapes direction over time.

Life begins to feel less like a series of pressures. It begins to feel like a field of participation. One is fully present, yet not overwhelmed. Action continues, yet it carries less agitation. Decisions reflect values rather than impulse.

This integration also brings kindness toward oneself. Feelings are no longer treated as mistakes. Sensations are no longer treated as commands. Responsibility becomes clear and humane. It rests in response, not in self-blame.

As reaction gives way to response, something settles inside. Not certainty, but clarity. Not control, but trust. Life continues to move. Awareness continues to watch. Within this living rhythm, authorship expresses itself quietly.

With this understanding in place, the inquiry reaches its natural closing. The final section reflects on what it means to reclaim the pen of one’s life in this grounded sense, and how steadiness becomes a way of living rather than an idea to hold.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Pen

As this reflection comes to rest, the central insight stands quietly in view. Life presents sensations. Heat and cold arrive. Pleasure and pain move through the body and mind. These experiences are part of being alive in a world of contact. They arise without asking. They pass without waiting. In this movement, authorship does not belong to arrival.

What shapes a life is how these sensations are met. Meaning is formed after experience appears. Direction is written in response. This is the steady teaching carried in Bhagavad Gītā Verse 2.14 (BG 2.14). Sensations are temporary. They come and go. The instruction is not to deny them. The instruction is to endure them with understanding.

When this is seen clearly, responsibility becomes simpler and more humane. One no longer feels compelled to manage every feeling. One no longer measures worth by comfort or discomfort. Responsibility rests in the capacity to pause. It rests in the ability to feel fully without being driven blindly. This pause creates room for discernment. It allows values to guide action.

Reclaiming the pen does not mean controlling the story of life. It means choosing how each line is lived. Reaction writes in haste. It repeats familiar patterns. Response writes with attention. It learns from experience. Over time, these responses shape character. They shape relationships. They shape the inner climate in which decisions are made.

This invitation is simple and demanding. Notice what arises. Pause before reacting. Respond with steadiness. These steps do not remove difficulty from life. They change the way difficulty is carried. Over time, this changes the shape of a life.

As you return to daily moments, the question remains alive. When sensation appears without asking, who responds? In that response, the pen is already in your hand.

Key Terms

Here are the key terms glossary in alphabetical order

- Āgama–Apāyinah: Arriving and departing experiences. It describes how sensations and feelings naturally come and go without permanence.

- Amygdala: The brain’s alarm for fear and anger. It rapidly detects threat and prepares the body for immediate reaction.

- Discernment: The capacity to pause and choose wisely. It allows response to arise from understanding rather than impulse.

- Guṇas: The three qualities of nature that shape experience. Sattva brings clarity and harmony, Rajas brings restless drive, and Tamas brings inertia.

- Mātrā-sparśa: Sense contact between the senses and their objects. It is the immediate source of pleasure and pain described in the Gītā.

- Puruṣa: Pure consciousness, the witnessing presence that knows experience. It remains unchanged by sensations, thoughts, or emotions.

- Prakṛiti: Nature or the field of experience. It includes the body, senses, mind, and emotional movements shaped by the guṇas.

- Reaction: An automatic response driven by habit and emotion. It arises quickly and often bypasses conscious choice.

- Response: A considered action shaped by awareness. It reflects responsibility and the capacity to choose direction.

- Sattva: The quality of clarity and harmony. It supports understanding, balance, and ethical action.

- Tamas: The quality of inertia and dullness. It clouds awareness and resists movement or effort.

- Rajas: The quality of restless drive and activity. It fuels ambition and urgency, often intensifying reactivity.

- Titikṣā: Forbearance or inner steadiness. It is the strength to remain present with sensation without collapsing into reaction.

- Witnessing Awareness: The capacity to observe experience without ownership. It allows sensations to be noticed without being authored.

Further Reading

For deeper insight into the themes explored in “Who is Authoring your life?”

- Swami Dayananda Saraswati. (2022). Bhagavad Gita (Bhagavad Gita Series, English). Arsha Vidya Research and Publication Trust. His lucid exposition of Bhagavad Gītā verses offers deep clarity on how experience, response, and self-knowledge are to be understood without confusion or emotional excess, especially in verses that address sensory contact and inner steadiness.

- Swami Chinmayananda. (1996). The Holy Geeta. Chinmaya Mission Trust. This commentary presents the Gītā as a manual for inner maturity, showing how disciplined response and thoughtful action shape a life lived with purpose across all stages and responsibilities.

- Swami Mukundananda. (2014). Bhagavad Gita: The Song of God. Plume. His accessible yet insightful explanations help connect the Gītā’s teachings on sensation, reaction, and forbearance with the psychological realities of modern life.

- Gross, J. J. (Ed.). (2014). Handbook of Emotion Regulation (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. A comprehensive resource that clarifies how regulation differs from suppression, supporting the article’s emphasis on steady response rather than impulsive reaction.

- Tang, Y. Y. (2017). The Neuroscience of Mindfulness Meditation: How the Body and Mind Work Together to Change Our Behaviour. Springer. Explores how sustained attention and awareness training strengthen the capacity to pause and respond with clarity, echoing the Gītā’s teaching of titikṣā in lived experience.

Note on Sources: This article draws primarily on the Bhagavad Gītā, with special attention to Verse 2.14, which speaks directly about sensory contact, pleasure and pain, and the practice of forbearance (BG 2.14). Supporting context is drawn from earlier verses that describe Arjun’s emotional and physical overwhelm on the battlefield, including his distress and loss of steadiness (BG 1.28–1.47). Together, these verses frame the inquiry into how experience arises without choice and how responsibility emerges through response rather than reaction.

The reflections are situated within the Vedāntic understanding of the Prasthāna-Traya, which includes the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gītā, and the Brahma Sūtras. Classical Vedāntic practices such as śravaṇa (listening to the teaching), manana (reflective inquiry), and nididhyāsana (deep contemplation) inform the article’s method. These practices support a gradual shift from intellectual understanding to lived clarity about awareness, response, and inner freedom. Standard English translations and traditional commentaries were consulted to maintain consistency and fidelity to the source texts.

The brain research perspective integrates established findings from neuroscience and psychology to illuminate how sensation, emotion, and regulation operate in everyday experience. These studies help explain why sensations trigger rapid reactions and how steady awareness strengthens the capacity to pause and respond with clarity:

Together, these sources support the article’s central theme. Sensation arises quickly and without permission. Inner steadiness develops gradually. Awareness, reflection, and practice shape how life is lived from within.

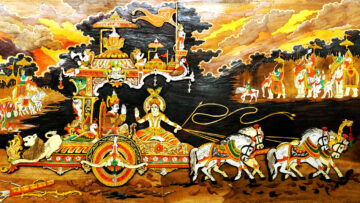

Feature Image Credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.