The following is a free-thinking essay that reflects on Nick Bostrom’s famed ‘simulation hypothesis,’ which posits that we are almost certainly living in a simulation. To the Hindu mind, this easily evokes the notion of māyā – that all of reality has an illusory nature. But deeper within, there are differences in nuance and teleology between these models. We structure the essay in the classic progression of pūrva pakṣa, uttara pakṣa, khaṇḍana, and samādhāna.

Pūrvapakṣa (Prima Facie View)

We first present the position of the simulation hypothesis as it stands, with all its apparent coherence and appeal to contemporary minds shaped by computational metaphors and digital realities. Nick Bostrom’s Simulation Hypothesis, articulated in his 2003 paper “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?”, proposes a trilemma that has captivated philosophical, scientific, and popular discourse. The argument proceeds with mathematical precision – If we accept that future civilizations might possess sufficient computational power to create ancestor simulations, i.e. detailed recreations of historical periods complete with conscious beings, then at least one of three propositions must be true. Either,

- Civilizations almost never reach a posthuman stage capable of running such simulations, or

- Posthuman civilizations have little interest in creating ancestor simulations, or

- We are almost certainly living in a simulation ourselves.

The logical structure is formidable. If thousands or millions of simulated realities could be generated by advanced civilizations, then the ratio of simulated consciousnesses to “base reality” consciousnesses would be overwhelmingly skewed toward the simulated. By pure probabilistic reasoning, any given conscious observer – including ourselves – would more likely be among the simulated rather than the original.

This hypothesis emerges from a distinctly materialist-computational framework. Consciousness, in this view, is substrate-independent – what matters is not whether awareness arises from biological neurons or silicon circuits, but rather the computational patterns and information processing that constitute mental states. The universe itself is then understood as a vast computational system, with physical laws serving as the “code” that governs the simulation. The pixelation of reality at the Planck scale, the speed of light as a processing limit, quantum mechanics as optimized rendering – these features of our cosmos find ready analogues in computational systems.

Bostrom’s position draws strength from the exponential growth of computing power, complemented by the development of increasingly sophisticated virtual realities, and the philosophical tradition of skepticism extending from Descartes’ evil demon to modern brain-in-vat scenarios. It speaks to a generation immersed in modern tech – video games, virtual worlds, and digital interfaces. The hypothesis appears to take seriously both – the possibilities of technological advancement, and fundamental questions about the nature of reality that have haunted philosophy since its inception.

The simulation hypothesis addresses perennial questions about existence – Why does the universe appear fine-tuned for consciousness? Perhaps because it was designed that way by the simulators. Why do we find ourselves in an era capable of contemplating such questions? Because we might be part of a historical simulation focusing on pivotal periods of development. The hypothesis offers a contemporary answer to ancient theological and metaphysical questions, replacing God with programmer, creation with code, and divine providence with algorithmic necessity. This itself is part of a particular schism in the modern psyche, detailed in the article here.

The hypothesis accommodates scientific investigations. If we live in a simulation, we might detect “glitches” – inconsistencies in physical laws, computational shortcuts in quantum mechanics, or patterns that reveal the underlying code. The hypothesis thus presents itself as a serious metaphysical position with potential empirical implications. Thus it has captured the imagination of many modern advocates, spawning endless discussion on simulation being a genuine possibility about the nature of our reality.

Uttarapakṣa (Response and Counter-Position)

Hindu traditions have contemplated the nature of reality, consciousness, and existence for millennia. On the surface we may find ready consonance with the simulation hypothesis’ core implication. The Advaitin would recognize, for example, that our ordinary waking experience is indeed “unreal” in a specific technical sense (mithyā), but this unreality is of an entirely different order than what Bostrom imagines.

From the perspective of Advaita Vedānta, the simulation hypothesis commits a fundamental category error. It confuses levels of reality, sattā, and mistakes the ontological status of the phenomenal world. Ultimately, the world is neither real (sat) nor absolutely unreal (asat). It has a dependent and provisional reality, like a rope mistaken for a snake gives the snake-appearance some kind of existence (affects the perceiver, generates fear, causes behavior). But it has no ultimate reality independent of the rope. Similarly, the phenomenal world appears and functions, but has no reality independent of Brahman.

The crucial distinction is between consciousness as the substrate versus consciousness as an emergent property.

The simulation hypothesis assumes that consciousness arises from matter via computational complexity, whether biological or artificial. It thus places computation as ontologically prior to awareness. But Vedānta reverses this hierarchy. Consciousness (cit) is the fundamental reality, the very ground of being, and all appearance of matter, energy, and information arises within it.

We may consider Śaṅkarācārya’s analysis of the three states of consciousness – jāgrat or waking, svapna or dreaming, and suṣupti or deep sleep. In the dream state an entire world appears – complete with space, time, causality, other beings, and one’s own dream-body. The dream-world has internal consistency, follows its own logic, and for the dreamer is experientially real. Yet we recognize upon waking that the entire dream-reality was a projection of consciousness, arising and subsiding within awareness without any external substrate. Dream mountains require no atoms, dream conversations send no sound waves, and dream colors are not animated by photons.

So what Bostrom calls “simulation”, Vedānta recognizes as a particular description of māyā – the creative, projective power of consciousness that manifests multiplicity from unity. Cast any which way, the rest is theology – even when it’s a technological simulation run by some external programmer. What’s essential is the inherent capacity of consciousness itself to appear as the many while remaining the one. The “simulator” and the “simulated” are ultimately advaita, non-different.

Sāṅkhya however posits two ultimate principles – puruṣa (pure consciousness, the witness) and prakṛti (the material principle with its three guṇas). The entire manifest universe is understood as the evolution of prakṛti in the proximity of puruṣa. Consciousness itself never changes, acts, or is affected – it merely witnesses the transformations of matter-energy.

For a Sāṅkhyist then, a simulation – no matter how sophisticated – is entirely on the side of prakṛti. It is merely a more subtle matter organizing itself in complex patterns. But the witness-consciousness is not and cannot be the simulated, as simulation itself is an object known to it. The Sāṅkhya Kārikā states –

“The soul is a witness, solitary, indifferent, a spectator, and inactive.”

This consciousness is not produced by any material complexity, computational or otherwise. It is the irreducible subject that can never be made into an object. In this way, Hindu thought not only anticipates but also resolves the inevitable infinite regress of causality that the simulation hypothesis sidesteps. If our reality is a simulation, what is the nature of reality of our simulators? Are they too simulated? To escape infinite regress, we must plead that some level is “really real” in a way that others are not. But on what grounds can we make such a distinction?

Vedānta recognizes that all levels of appearance, whether we call them base reality or simulation, have the same ontological status relative to the one true reality of Brahman. The question “is this a simulation” is technically the wrong question. The right question is – “What is the nature of the self that witnesses all appearance, including this question itself?”

To this, an epistemological dimension is added by Nyāya, through its rigorous analysis of the pramāṇas, or valid means of knowledge. Naiyāyikas recognize four valid means of knowledge – pratyakṣa or perception, anumāna or inference, upamāna or comparison, and śabda or testimony. The simulation hypothesis relies heavily on inference, but Nyāya would challenge whether the inference is properly grounded.

An inference is valid only when it moves from a known, observed correlation – vyāpti – to a new instance. We infer fire from smoke because we have repeatedly observed fire and smoke together. But what is the observed correlation that grounds the inference that we are likely to be in a simulation? We have no experience of simulations sophisticated enough to contain fully conscious beings. The inference leaps from our capacity to create primitive proto-simulations to the likelihood that we inhabit a perfect one.

From the Yoga tradition, we know of various states of samādhi, or meditative absorption, in which the ordinary structures of perception dissolve. In nirvicāra samādhi and higher states, the distinction between subject and object, perceiver and perceived, collapses. The yogi experiences consciousness in its pure form, prior to and independent of all content, all simulation, all appearance. But this would be impossible, if consciousness were truly reducible to computational patterns. One cannot step outside of a simulation if one is nothing but a process within it. Yet the yogika tradition reports, with remarkable consistency across centuries, that consciousness can be known directly, in itself, apart from all objects and experiences. An empirical observation verified through contemplative practice offers a direct refutation of the simulation hypothesis.

Further, the hypothesis fails to account for the qualitative, first-person nature of consciousness. Modern science calls this “qualia,” and Vedānta calls it the sākṣi – witness. No description of computational processes captures the subjective felt quality of experience – the redness of red, the painfulness of pain, the bliss of love, the joy of joy. This reflects a category difference. Computational descriptions are third-person, quantitative, and structural. But consciousness is first-person, qualitative, and intrinsic. To assume that the latter emerges from the former is like trying to extract wetness from the concept of water rather than from water itself.

Hindu thought also maintains that the cosmos is structured by ṛta (cosmic order) and dharma. Actions have real consequences that extend across lifetimes, creating kārmika patterns that shape future births. If reality is a simulation, what becomes of moral responsibility, dharma, and the accumulated effects of action? A simulated reality would suggest that consequences are ultimately arbitrary – they are whatever the programmer, or code, decides. It undermines the entire foundation of ethical life.

But the very fact that we recognize distinctions between right and wrong, that we feel the weight of moral obligations – these point to a real moral structure to the universe. Some simulation theorists posit the existence of a stable-code morality – a value-based order implicit in the universe that is coded into its fabric by the simulators. But if we are to imagine simulators that have a moral code and yet endow units within their simulation with free-will, we may as well revisit Epicurus’ famous questions on the nature of evil and suffering.

A final consideration comes from the Vaiśeṣika lens. The simulation hypothesis reduces all categories to information or computation in a kind of metaphysical monism that flattens the rich categorical structure of existence. Vaiśeṣika recognizes dravya, guṇa, karma, sāmānya, viśeṣa, and samavāya as fundamental categories of reality. Each has its own nature and cannot be reduced to the others. Vaiśeṣika further distinguishes between different types of causes – material cause, efficient cause, and inherent cause.

The simulation hypothesis conflates these categories. It treats the “simulator” as an efficient cause but does not specify what serves as the material cause of consciousness itself. If consciousness is supposedly generated by the simulation, what is it made of? Information? But information requires a conscious observer to be information to begin with, otherwise it is merely patterns of matter-energy!

Khaṇḍana (Refutation and Critique)

The simulation hypothesis takes a metaphor – the universe as a computation – and reifies it into a literal ontological claim. In this sense it is no different to earlier speculations that relied on the universe as a clock, or as a machine. Each age projects its dominant technology and taxonomy onto the cosmos, mistaking the map for the territory. The Hindu response to this is incisive – all metaphors, descriptions, conceptual frameworks are ultimately within māyā, within the realm of nāmarūpa – name and form. They are pragmatic devices that have relative utility, but should never be confused with the ultimate truth. But the simulation hypothesis mistakes a contemporary metaphor for a revelation about reality.

This is a failure of proper definition. A simulation, properly defined, is a representation that is known to be distinct from what it represents. But if our entire reality is itself simulated, then the concept of simulation loses all meaning. We have no independent standpoint from which to make the comparison between simulation and reality, and our framework collapses into incoherence.

Of course, the deepest refutation concerns consciousness itself. The simulation hypothesis assumes that consciousness can be “uploaded,” “instantiated,” or “run” on a computational substrate. The assumption is never argued for, it is merely asserted as obvious and given. But the Hindu tradition recognizes consciousness as fundamentally different in kind from matter. And this assertion is not lightly made, it is based on careful phenomenological analysis and contemplative investigation.

Consider the argument from the self-luminosity of awareness. Consciousness is considered to be svaprakāśa – self-revealing – and it does not require another to know it. A simulation, being a complex object or process, would itself need to be known by consciousness. To say that the simulation produces consciousness is like saying darkness produces light, or that the seen produces the seer. It reverses the actual order of ontological dependence. Sāṅkhya is even more precise – prakṛti is characterized by object-ness, changeability, and composition. Puruṣa is characterized by subject-ness, unchangeability, and simplicity. These are two distinct types of reality, and no amount of complexity in the object-realm can cross the categorical divide to become the subject.

Now, if the simulation hypothesis were true, all meaning, value, and purpose would be ultimately arbitrary. But this contradicts our deep experience of meaning as intrinsic to existence. We recognize that dharma, ṛta, and the moral structure of the universe are necessary features of reality. Moreover, if we are simulations, then so are our experiences of meaning, value, and truth. The very concepts used to formulate the simulation hypothesis – logic, reason, evidence – would themselves be simulations. And then we have no grounds for confidence in our reasoning. The hypothesis is pragmatically self-refuting.

Even if we accept the hypothesis, it changes nothing about the practical reality of suffering and the need for liberation. A simulated pain hurts just as much as a “real” pain. And the quest for mokṣa or nirvāṇa remains relevant regardless of the metaphysical status of the world in which this suffering occurs. This offers a provocative counter to the technological teleology that the simulation hypothesis inspires. Elon Musk, when asked what he would ask the simulators were he to ever meet them, responded – “What lies outside the simulation?” Futuristic imaginations on the hypothesis picture a scenario where we may be able to transcend the simulation and eventually escape it. But quite like the panspermia theory for the origins of life, such a model simply shifts our queries a level up without actually resolving them. If life came to earth from elsewhere in the universe, how did it originate there in the first place? Similarly, if we are a simulated reality, all our existential questions are simply shifted up to the level of base reality – they are not answered.

The hypothesis cannot escape the problem of infinite regress. If we are simulated, what simulates the simulators? And what simulates them? Either we have an infinite tower of simulations, or we arbitrarily stop at some level and declare it “base reality.” But the Hindu tradition recognizes that this question itself arises from avidyā or ignorance. All levels of appearance are equally māyā – phenomena appearing within the one, non-dual Brahman. There is no infinite regress because there is no multiplicity of levels. There is only the appearance of multiplicity, within the singular reality of consciousness.

So the Advaitin might say that we are not in a simulation, we are intelligence itself – appearing as both simulator and simulated, dreamer and dream. The solution is to realize the identity within the one reality that is neither simulated nor simulator – pure consciousness itself. And the Advaitin might recruit the Naiyāyika’s help in escaping from the simulation hypothesis’ epistemological trap. The hypothesis uses reason to arrive at a conclusion that undermines reason. But Hindu tradition maintains that while our perceptions may be mistaken, our inferences flawed, there exists a valid means of knowledge – direct realization or anubhava – which is self-validating and independent of external verification.

Samādhāna (Resolution and Synthesis)

Having examined and refuted the simulation hypothesis from multiple angles of the Hindu darśanas, we now arrive at samādhāna – a resolution that preserves what is true in Bostrom’s intuition while correcting its fundamental errors and integrating it into the deeper framework of Hindu understanding. To be fair to Bostrom, his hypothesis captures something genuine about the nature of our experienced reality. When he suggests that our world might not be the “base level” of existence, he is, in a distorted modern idiom, approaching the ancient insight that the phenomenal world is not ultimately real, that appearances are not the final truth.

His intuition that consciousness could exist in a reality “created” by something beyond itself – while wrong in its computational framework – echoes the Vedāntika recognition that the individual consciousness and its experienced world are appearances within a larger reality. The sense that reality might be “designed” or “programmed” with specific parameters is not entirely unlike the recognition that the universe manifests according to dharma, ṛta, and the laws of karma. Even the probabilistic reasoning – the sense that we are more likely to be in one of many derivative realities rather than the single original – parallels the Vedāntika teaching that we are more likely to be caught in māyā (as most people are) than to have realized our identity with Brahman (as few do).

The fundamental correction the Hindu darśanas offer is the reversal of the ontological hierarchy. The simulation hypothesis assumes – computation → complexity → consciousness. The Hindu understanding is – consciousness → appearance → complexity. Consciousness is not a product of simulation, simulation (and all appearance) is a modulation of consciousness. The universe is consciousness knowing itself, appearing to itself as the multiplicity of phenomena.

For if consciousness is the substrate, then –

- The hard problem of consciousness dissolves. There is no need to explain how subjective experience arises from objective processes because the subjective (consciousness) is ontologically prior to the objective (appearance).

- The infinite regress problem is resolved. There is no need for an infinite tower of simulations or simulators. All appearance, at whatever “level,” arises within the single reality of consciousness.

- The epistemological trap is avoided. We can trust our cognitive faculties (when properly trained and purified) because consciousness, knowing itself, is self-validating. The pramāṇas are expressions of consciousness’s inherent capacity for self-awareness.

- Meaning and value are preserved. Dharma, karma, and the moral structure of the universe are necessary features of how consciousness manifests as the many.

The resolution is the recognition of Brahman as the sole reality – infinite consciousness-existence-bliss that appears as the universe through the inexplicable power of māyā. What Bostrom calls “base reality” is the relative reality of vyavahāra – the empirical world of transactions and multiplicity. What he calls “simulation” is also vyavahāra – just another appearance within consciousness. Both “levels” are equally real relative to ordinary experience and equally unreal relative to Brahman.

The question “Are we in a simulation?” is, from this perspective, a distraction from the more important question – “What is the nature of the self that asks this question?” The answer to this second question – that you are not the limited individual but the infinite consciousness in which all worlds appear – is liberating (mokṣa) in a way that the answer to the first question could never be. Even if we discovered definitive proof that we are in a simulation, it would change nothing about the practical necessity of dharma, the reality of suffering, or the possibility of liberation. And even if we discovered we are in “base reality,” we would still need to recognize that this base reality is itself māyā relative to Brahman.

The Hindu tradition goes beyond metaphysical theories and offers practical methods for moving from confusion to clarity, from bondage to liberation. The simulation hypothesis, while intellectually interesting, offers no such path. It leaves us trapped in speculation about our metaphysical status without any means of resolution. Consider Hinduism’s concrete practices – ethical cultivation (yama-niyama), physical discipline (āsana), breath control (prāṇāyāma), sensory withdrawal (pratyāhāra), concentration (dhāraṇā), meditation (dhyāna), and absorption (samādhi) – that lead to direct realization of consciousness in itself.

The Hindu response also attends to the social and ethical implications that the simulation hypothesis overlooks. If life is a simulation, one might be tempted toward nihilism or amorality – after all, nothing “really” matters. But the dhārmika worldview recognizes that our actions have real consequences, creating kārmika patterns that follow us through multiple lifetimes.

The concept of līlā (divine play) offers an interesting parallel and contrast to the simulation hypothesis. The universe is indeed a kind of “play” of the divine consciousness, but it is not arbitrary or meaningless. It is the way the infinite enjoys itself, manifesting as the many while remaining the one. Each jīva is a real participant in this play, with genuine agency, real relationships, and meaningful choices. Furthermore, whether the world is “simulated” or not, compassion (karuṇā) is called for, wisdom (prajñā) is to be cultivated, and liberation (mokṣa) is to be sought.

To be clear, Hindu thought does not reject the technological insights that inspire the simulation hypothesis. Advances in computing, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence are remarkable achievements of human intelligence (buddhi). But they must be properly contextualized. Technology operates within the realm of prakṛti – it is the manipulation of subtle and gross matter to produce desired effects. This is valuable and legitimate within its domain. The error arises when we extrapolate from our technical capacities to ultimate metaphysical conclusions.

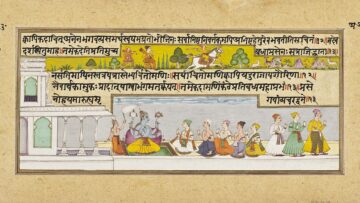

The Yogavāsiṣṭha contains numerous stories of nested realities, worlds within worlds, dreams within dreams – prefiguring much of what the simulation hypothesis suggests. But it uses these stories pedagogically, to loosen our attachment to the “reality” of the phenomenal world and point us toward the recognition of consciousness as the sole reality. Similarly, we might appreciate the simulation hypothesis as a modern myth, a story that captures something true about the dreamlike quality of experience, without taking it literally as a scientific or metaphysical truth claim.

The final resolution is the recognition of non-duality (advaita). The simulation and the base reality, the simulator and the simulated, the subject and the object – all these apparent dualities are resolved in the non-dual awareness of Brahman. This is non-duality – the recognition that apparent multiplicity arises within and is non-different from the singular reality of consciousness. Brahman is that in which all apparent things appear and which they all truly are.

The value of engaging with the simulation hypothesis is in using it as a starting point for deeper inquiry. It can serve as a gateway, leading modern minds accustomed to computational metaphors toward the more profound recognition that reality is indeed not what it appears to be – because we have forgotten our identity as the infinite consciousness in which all worlds arise. The invitation of the Hindu tradition is to undertake the practices that lead to direct knowledge of the self. Through meditation, self-inquiry, and the grace of a realized teacher, one can move from the confusion of māyā to the clarity of vidyā, from the limitation of jīva-bhāva (identification with the individual) to the freedom of Brahma-bhāva (identification with the infinite).

In this light, the simulation hypothesis, for all its contemporary sophistication, is seen as a finger pointing at the moon – potentially useful if it directs attention toward genuine inquiry, but disastrous if mistaken for the moon itself. The moon – the truth of consciousness as the sole reality – shines equally on all, waiting only for the clearing of vision that comes with sustained practice and grace. Tat tvam asi—You are That. This is the ultimate resolution – that you are the reality in which all simulations, all worlds, all appearances arise. This recognition is a truth to be realized, transforming our very being, from the bondage of ignorance to the freedom of knowledge, from the fragmentation of multiplicity to the wholeness of non-dual awareness.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.