Reclaiming a Lost Epistemology

Nyāya, one of the six classical darśanas of Indian philosophy, stands as a rigorous science of reasoning and cognition. Its goal is to attain valid knowledge, or pramā. This goal is achieved through disciplined inquiry, clear perception, and precise reasoning. Nyāya articulates a comprehensive cognitive architecture that anticipates—and in many respects surpasses—key principles of modern epistemology. These aspects include structured inference, dialogical examination, and error classification. It offers a systematic method for acquiring true knowledge, correcting errors, and deepening understanding through the integrated use of reason, perception, and ethical intent.

This tradition was transmitted through a deeply embedded oral pedagogy. The guru-śiṣya paramparā formed the backbone of Indian intellectual culture, where knowledge was passed through dialogical engagement, memorisation, and lived instruction. Central to this transmission was the sūtra-paddhati—a method of encoding vast philosophical insight into terse aphorisms. Each sūtra functioned like the tip of an iceberg: a compact verbal form concealing a vast substratum of interpretive depth, experiential practice, and societal application. The sūtra holds its meaning in condensed depth, revealed gradually through the teacher’s elucidation, the student’s inquiry, and the contextual reflection that brings it to life.

This ecosystem of knowledge endured for millennia, shaping generations of thinkers, practitioners, and communities. The decline of the Vijayanagara Empire, followed by the rise of colonial education—especially Macaulay’s utilitarian model—disrupted this continuity. What had been a living science of cognition gradually became marginalised, surviving only in textual fragments and academic footnotes.

Compounding this loss was a shift in interpretive framing. The sūtras of the darśanas were originally defined with the precision of physical laws— technically exact, mutually exclusive, and universally valid. Yet in many modern renderings, they came to be loosely translated as metaphysical or speculative philosophy. This misreading, shaped by Western conceptual overlays, diluted their scientific clarity and epistemic intent.

This essay seeks to restore Nyāya’s stature as a structured science of knowledge—one that offers not only historical insight but also lasting relevance to modern epistemology and scientific thought. By unpacking the first sūtra of Nyāya and tracing its four-phase model of inquiry, we uncover a system that integrates perception, reasoning, theory formation, and dialogical examination. In doing so, we reclaim Nyāya not as a relic of the past, but as a living architecture of valid knowing.

Nyāya’s Foundational Sūtra: A Cognitive Map

The Nyāya Darśana begins with a deceptively compact yet profoundly layered aphorism:

प्रमाण-प्रमेय-संशय-प्रयोजन-दृष्टान्त-सिद्धान्त-अवयव-तर्क-निर्णय-वादा-जल्प-वितण्डा-हेत्वाभास-चल-जाति-निग्रहस्थानानां तत्त्वज्ञानान् नि:श्रेयसाधिगमः।

“Pramāṇa-prameya-saṁśaya-prayojana-dṛṣṭānta-siddhānta-avayava-tarka-nirṇaya-vāda-jalpa-vitaṇḍā-hetvābhāsa-chala-jāti-nigrahasthānānāṁ tattvajñānān niḥśreyasādhigamaḥ.”

This opening sūtra of the Nyāya Sūtras, attributed to Akṣapāda Gautama, is often mistaken for a mere enumeration of sixteen categories (padārthas). However, it is far more than a list—it is a processual map of inquiry, a cognitive sequence that guides the seeker from perception to resolution, from doubt to dialogue, and ultimately toward tattvajñāna—true knowledge of reality.

Each term in the sūtra represents a distinct phase or instrument in the pursuit of valid knowledge.

- Pramāṇa (means of knowledge) initiates the process of acquiring valid knowledge,

- Prameya (object of knowledge) anchors it,

- Saṁśaya (doubt), Prayojana (purpose), and Dṛṣṭānta (example) guide and propel the process of inquiry,

- Siddhānta (established theory) and its Avayava (constituent components) form the structured theory.

- Tarka (hypothetical reasoning) and Nirṇaya (decisive judgment) refine cognition,

- Vāda (truth-seeking inquiry) tests it,

- While Jalpa (victory-seeking inquiry), Vitanda (fault-finding inquiry), Hetvābhāsa (incorrect reasoning), Chala (shifting/evasive inquiry), Jāti (pseudo-rebuttal), and

- Nigraha-sthāna (halt point) is a technical term in Nyāya and other śāstric It denotes the specific flaw or ground due to which an inquiry is brought to a close. It marks the point at which further reasoning is suspended—either because the position has been refuted, or because it stands provisionally accepted until new counter-theories emerge. The current theory, having reached its limit of defensibility or coherence, is either upheld or set aside, pending future examination.

Together, these categories constitute a dynamic architecture rather than static definitions. They reflect a tradition where knowledge is earned through disciplined cognition, ethical inquiry, and self-correction.

The very definition of Nyāya affirms this orientation:

नीयते प्राप्यते यथार्थ पदार्थज्ञानं येन स न्यायः।

“Neeyate prāpyate yathārtha padārtha-jñānam yena sa nyāyaḥ”

“That by which one is led to and attains true knowledge of real entities—that is Nyāya.”

This definition underscores Nyāya’s purpose: to guide the intellect toward yathārtha-jñāna—accurate, reality-aligned cognition. It is an active method of knowing, theorising, correcting, and refining. In this light, the foundational sūtra is not a taxonomy but a cognitive blueprint—a knowledge-based journey encoded in sixteen steps.

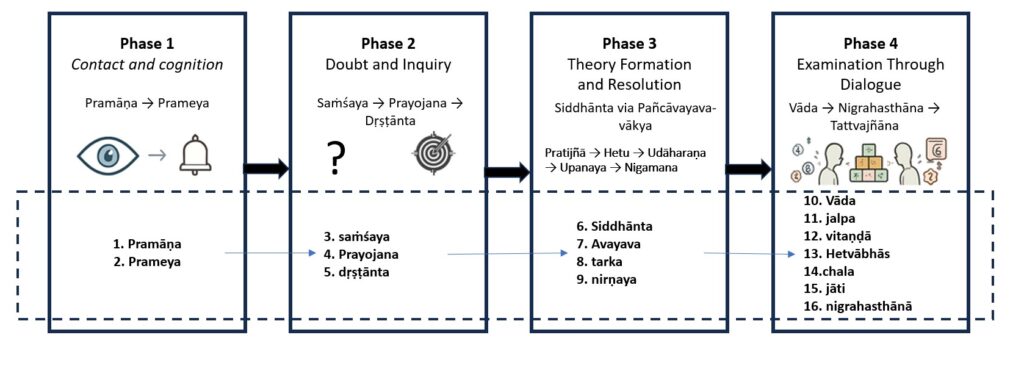

(Figure 1: Nyāya’s Cognitive Architecture—A Four-Phase Map of Valid Knowledge. This diagram selectively visualizes key padārthas as functional phases within Nyāya’s epistemic flow. Categories such as tarka, nirṇaya, hetvābhāsa, and nigrahasthāna are contextually embedded within broader phases like siddhānta and vāda, preserving the integrity of the sixteenfold schema while emphasizing operational synergy.)

Phase 1: Contact and Cognition

Nyāya’s cognitive journey begins with the foundational pairing of pramāṇa (means of knowledge) and prameya (object of knowledge). This pairing marks the first moment of cognitive engagement—the encounter between the knower and the known. At this juncture, knowledge arises through one or more instruments of cognition, depending on the nature of the object and the context.

Nyāya recognizes four such instruments: pratyakṣa—perception through direct sensory contact; anumāna—inference based on observed patterns; upamāna—analogical comparison; and śabda—verbal testimony from a trustworthy source (āpta). While all four are active from the outset, this phase is best illustrated through pratyakṣa, the most immediate and accessible mode of knowing. For instance, when the eye comes into contact with a clay pot under appropriate conditions—adequate light, a functional sense organ, and an attentive mind—a perceptual cognition arises: “This is a pot.” Here, the pramāṇa is perception, and the prameya is the pot as a knowable entity.

Importantly, this initial moment is not passive reception but an active alignment of faculties—sense organ, mind, self, and object. Nyāya’s brilliance lies in its insistence that even this first step is subject to scrutiny. Perception must be free from misrepresentation, illusion, and doubt. This is the first qualification for valid knowledge.

Thus, the first phase of Nyāya’s cognitive architecture lays the foundation for knowing: it defines the conditions under which cognition arises and the instruments by which it is reliably obtained. It is a phase of contact, recognition, and the careful discernment of what counts as knowing.

Phase 2: Doubt and Inquiry

Once initial cognition has occurred—through valid contact between the knower and the known—the Nyāya system enters its second phase: saṁśaya, or doubt. Far from being a hindrance, doubt is treated as a necessary and productive moment in the cognitive journey. It signals the presence of conflicting impressions and marks the transition from passive recognition to active inquiry.

Doubt arises when the mind encounters uncertainty—whether due to similarity between objects, conflicting features, contradictory prior knowledge, or lack of clarity about what is present or absent. This uncertainty prompts inquiry, guided by purpose and example, leading the mind toward resolution. While Nyāya rigorously defines these forms of doubt with technical precision, they are presented here in simplified terms to suit the scope and flow of this essay.

This cognitive tension compels the seeker to investigate further. Yet inquiry is not aimless—it is directed by two guiding aids:

- Purpose (prayojana): the motivating reason for resolving the doubt, which defines the relevance and urgency of the inquiry.

- Example (dṛṣṭānta): a known instance or analogy that helps clarify the unknown through comparison or illustration.

Together, purpose and example provide the framework for systematic investigation. They orient the mind toward resolution and offer a structure for testing possibilities. In modern terms, this phase resembles hypothesis formation—where the mind, faced with uncertainty, formulates a tentative proposition and seeks evidence or reasoning to confirm or refute it.

Nyāya’s treatment of doubt is thus deeply methodological. It does not dismiss uncertainty but harnesses it as the engine of inquiry. By recognizing doubt as a legitimate cognitive state and embedding it within a structured process, Nyāya affirms that the path to valid knowledge begins not with certainty, but with the courage to question.

Phase 3: Theory Formation and Resolution

Once doubt (saṁśaya) has been recognized and inquiry initiated, the Nyāya system advances into its third phase: the formation of a siddhānta, or established theory. This is not a casual opinion but a carefully reasoned position—one that has withstood scrutiny through structured reasoning and dialogical examination. The goal of this phase is to arrive at niḥsaṁśaya: a state of doubt-free conviction grounded in rational clarity.

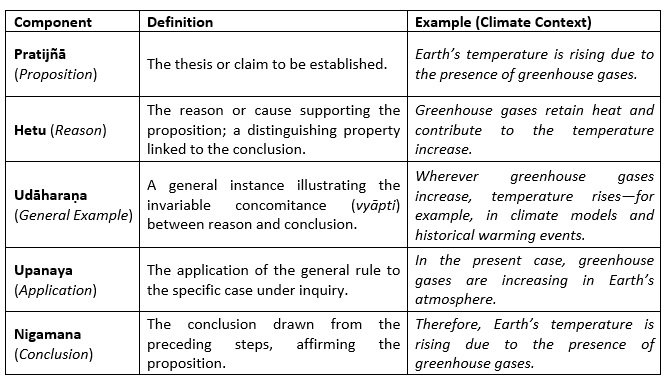

At the heart of this phase lies the pañcāvayava-vākya, or five-part sentence, which serves as the formal structure for articulating and validating a theory. Each component plays a distinct epistemic role, as outlined in Table 1.

(Table 1: Structure of Pañcāvayava-Vākya with Climate-Based Example)

This five-part structure ensures that the conclusion is verifiable through reasoning. It reflects Nyāya’s commitment to reasoned justification —every claim must be traceable to its cognitive and logical roots

To arrive at a siddhānta, Nyāya employs two key strategies:

- Tarka (hypothetical reasoning): This involves imagining possible scenarios or consequences based on causal logic and inference. It tests the plausibility of a claim by exploring its implications. If a proposed cause leads to a contradictory outcome, it is rejected.

- Nirṇaya (decisive judgment) emerges through comparative evaluation of two structured evidential modes — pakṣa, the presence of corroborative instances (e.g., observing smoke where fire is present), and pratipakṣa, the absence of expected evidence where the phenomenon is negated (e.g., no smoke where there is no fire).

While tarka tests the internal consistency and causal plausibility of a theory through hypothetical reasoning, nirṇaya establishes its external validity by comparing positive and negative instances of evidence.

Together, tarka and nirṇaya serve as the cognitive engine of theory formation. They refine the raw material of doubt into structured insight, ensuring that the emerging siddhānta is not only logically sound but also resilient to challenge.

This phase culminates in the resolution of doubt. But this is not dogmatic closure; it is a provisional stability, always open to further refinement through dialogue and examination. In this way, Nyāya models an ongoing pursuit of valid knowledge: one that values certainty, but only as the earned outcome of rigorous, ethical, and transparent reasoning.

While the five-part sentence formalizes the structure of reasoning, Nyāya also prescribes procedural instruments that ensure the theory’s resilience against error.

Phase 4: Examination Through Dialogue

The final phase of Nyāya’s cognitive architecture is dialogical examination. In this phase, theories are tested through structured inquiry. It is a core method for forming reliable knowledge. Nyāya holds that clarity comes through disciplined exchange.

The ideal mode of such exchange is vāda. It is a truth-seeking dialogue conducted with sincerity, logic, and ethical intent. In vāda, participants aim not to win or defeat but to confirm understanding. It is a collaborative inquiry. The goal is resolution of doubt (niḥsaṁśaya), not verbal dominance.

Nyāya explicitly cautions against two inferior modes of inquiry or dialogue:

- Jalpa: Disputative engagement driven by the desire for victory, often marked by aggressive posturing, selective reasoning, and disregard for truth.

- Vitaṇḍā: Destructive criticism where the opponent attacks without offering a counter-thesis, aiming only to dismantle the other’s position.

To preserve the integrity of vāda, Nyāya offers a detailed taxonomy of dialogical errors and breakdowns, which serve as diagnostic tools during inquiry:

- Hetvābhāsa (fallacious reason): Apparent logic that fails under scrutiny, such as irrelevant, contradictory, or unverified causes.

- Chala (quibbling): Deliberate distortion of terms or meanings to mislead or derail the inquiry.

- Jāti (pseudo-rebuttals): Deceptive counterarguments that misuse analogies, definitions, or exceptions.

- Nigrahasthāna (Halt points): Twenty-two specific conditions under which a proposed theory is accepted or collapses due to logical, linguistic, or ethical failure.

These categories do not merely mark failure—they illuminate its nature. They help distinguish between superficial disagreement and genuine error in knowledge acquisition, enabling participants to refine their reasoning and uphold the standards of inquiry.

In this way, Nyāya’s dialogical phase mirrors the rigor of peer review in modern scientific discourse. Just as scientific theories are tested through replication, critique, and falsification, Nyāya’s siddhānta is tested through vāda, where reasoning is exposed to challenge and refined through response. The emphasis on ethical conduct, linguistic precision, and fallacy recognition ensures that debate remains a tool of knowledge, not a weapon of ego.

Thus, the fourth phase completes the Nyāya cycle: from perception to doubt, from theory to testing. It affirms that valid knowledge is not merely constructed—it is earned through the crucible of reasoned dialogue.

(Figure 2: Nyāya’s Cognitive Architecture—A Four-Phase Map of Valid Knowledge. This diagram embeds all the sixteen categories in the process)

Nyāya as a Living Science

Nyāya is often mischaracterized as a static enumeration of philosophical categories. In truth, it is a dynamic cognitive architecture—a living system of inquiry that guides the mind from raw perception to refined understanding, from doubt to resolution, and from theory to dialogical testing. Each phase of this cognitive sequence is not merely descriptive but operational, designed to cultivate pramā—valid, reality-aligned cognition.

This architecture remains profoundly relevant to modern science, logic, and artificial intelligence. In scientific practice, Nyāya’s emphasis on structured reasoning, fallacy detection, and dialogical integrity parallels the core principles of hypothesis testing, peer review, and falsifiability. Its five-part sentence anticipates formal logic systems, while its classification of cognitive errors—hetvābhāsa, chala, jāti, and nigrahasthāna—offers a diagnostic framework that could enrich contemporary models of reasoning and machine learning.

In the context of AI and cognitive modeling, Nyāya provides a template for designing systems that not only process data but evaluate the validity of their own inferences. Its layered approach to perception, inference, and correction aligns with the goals of explainable AI, where transparency, traceability, and ethical reasoning are paramount.

To reclaim Nyāya as a living science is to restore a tradition of disciplined inquiry that integrates logic, ethics, and cognition. It is not a relic of the past but a framework for the future—one that can inform not only philosophical discourse but the very architecture of intelligent systems and scientific reasoning.

Nyāya offers more than a historical account of Indian reasoning—it presents a timeless framework for structured inquiry, dialogical ethics, and humility in knowledge. Its cognitive architecture, from pramāṇa to nigrahasthāna, reflects a system where knowledge is not merely acquired but earned through perception, inference, theory formation, and rigorous examination. It affirms that truth is constant, but can be understood progressively, cultivated through disciplined reasoning and ethical engagement.

In an age where scientific precision often outpaces reflective depth, Nyāya reminds us that knowing rightly is as much a moral act as an intellectual one. Its emphasis on fallacy recognition, dialogical integrity, and cognitive self-awareness offers tools urgently needed in contemporary fields—from cognitive science and ethics to artificial intelligence and systems of inquiry.

To engage with Nyāya today is not an exercise in nostalgia—it is a step toward plural modes of reasoning, where diverse traditions of inquiry enrich our understanding of knowledge itself. It is also a gesture of intellectual sovereignty, reclaiming indigenous frameworks long sidelined by colonial and positivist paradigms.

Reviving Nyāya is thus not merely about restoring a philosophical system—it is about restoring cognitive integrity: the capacity to think clearly, reason ethically, and inquire responsibly. In doing so, we not only honor a profound tradition but also equip ourselves to meet the challenges of knowledge in the present and future.

References

Annam Bhaṭṭa. Tarka Saṅgraha with Dīpikā. Edited with notes by Swami Virupakshananda. Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1994.

Gautama Maharshi. Nyāya Mīmāṁsa Darśanamu. Translated by Charla Ganapati Sastry. Hyderabad: Lalita Press, 1977.

Olszewski, Wojciech, and Alvaro Sandroni. “Falsifiability.” The American Economic Review 101, no. 2 (2011): 788–818. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29783690.

Popper, Karl. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: Hutchinson, 1959.

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli. Indian Philosophy. Vol. 1: Theistic Schools. London: Oxford University Press, 1923.

Renuka KC. “The Concept of Pramā and Pramāṇa in Nyāya Philosophy.” Ananta Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 10, no. 4 (2024). https://www.anantaajournal.com/archives/2024/vol10issue4/PartA/10-3-57-729.pdf.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank Prof. G. Narahari Sastry, Dean, IIT Hyderabad, for his constant guidance and for helping me balance traditional Indian thought with contemporary perspectives. His support has been invaluable in shaping the direction and depth of this essay.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. G. Songeeta for her insightful discussions, which greatly enhanced the clarity and philosophical precision of the work.

My daughter, Ms. Akanksha Garikapati (Masters in Performing Arts), offered a thoughtful editorial review of the article.

Feature Image credit: istockphoto.com

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.