In diagnosing the modern condition as one of “disenchantment”, Max Weber captured something fundamental about the Western civilization’s trajectory. Carl Jung put it more provocatively –

“It is quite possible that India is the real world, and that the white man lives in a madhouse of abstractions.”

Both speak of a world where divinities no longer preside over the forest and trees, thunder merely announces meteorological conditions; and the rivers flow without spirit. It is an evacuation of ‘the beyond’ from matter, a removal of the numinous from the everyday world. And it seeds a profound schism in the psyche that lives so.

The origins of this split in psyche lie deep in the Western tradition. Judeo-Christian monotheism, with its dismissal of anything other than a singular, transcendent deity, separates the divine from the natural world. Where pagans see gods in every grove, spring, rock, and hill, the Abrahamic mind observes a creation pointed towards, but not containing, its very creator. And though modern rationalism likes to stand apart from its Judeo-Christian roots, it borrows from the same theological architecture, submitting all phenomena to mechanical explanations and reducing reality only to the measurable.

In this trajectory, the great Scientific Revolution completed what monotheism had begun. Descartes split mind from the body and created a dualism that rendered matter inert, consciousness a ghost in the machine. Newton’s clockwork universe followed a predetermined arrow of time – beautifully precise, coldly deterministic. Enlightenment elevated reason to the final throne, banishing mystery and magic in its war on superstition. And so, by the time industrial modernity arrived, the world had been left thoroughly disenchanted. Today, the technological man considers consciousness emergent from matter, and defines it as “how information feels when processed in increasingly complex ways.” A random occurrence in a dead universe, set in motion by a blind watchmaker.

But this resolute march faces a blunt reality – humanity is constitutionally incapable of living in a purely material world. Its psyche hungers for meaning, for connection to something beyond, and its deepest intuitions insist that consciousness extends beyond the fortress of the skull. Its felt experience resonates, as Terence McKenna said, that “there is a mystery out there.” So when the natural door to transcendence closes, human imagination searches for windows, for cracks in the wall, for any smallest slit through which the numinous might yet return – or at least confirm its presence. And nested within the modern psyche’s highest imaginations is a constant yearning to reconnect with the non-material.

Modern Yearnings for the Beyond

Modern language, equipped with the taxonomy of technology and computation, gives us novel ways to describe what ancient humans put differently. Consider our obsession with the simulation hypothesis, the idea that our reality might be a computer program run by a higher intelligence. The notion animates the imagination of Silicon Valley titans and internet philosophers alike, generating endless speculation, debate, and even teleology – prompting Elon Musk to openly ponder, “what lies outside the simulation?” Given the taxonomy used, the idea appears thoroughly modern, even cutting-edge.

But the simulation hypothesis is a technological repackaging of classical metaphysical questions. The demiurges become programmers or simulators, ṛta or the logos become the code, and māyā is the simulation. Where the ancients believed the material world to be a kind of reflection of the eternal reality, simulation theorists are comforted by describing the same structure with theological language swapped out for computational metaphors. The hunger remains identical – a desire to pierce the veil of appearances and glimpse the true nature of reality. Deeper still – to confirm that this world of matter cannot be all there is.

This extends to another modern, post-technological fascination – aliens and UFOs, the latter now more often called UAPs (unidentified anomalous phenomena). Once dismissed as fringe phenomena, they have entered mainstream discourse in a big way. UFOlogists and “alien civilization experts” frequent the rounds on major podcast channels, telling us of everything from the aliens observing modern nuclear plants to the Annunaki that guided Sumerian civilization. The modern mind is unable to accept what the ancient civilizations themselves claimed – that they were in living engagement with non-material divinities. But the same mind feels very scientific and modern in explaining this as encounters with aliens from a secret tenth planet, or future time-travellers, or other imaginations drawing from a variety of science fictional ideas.

But even rooted in a different cultural context, such speculations serve the same spiritual function, though less consciously. Aliens, time-travellers, post-human visitors – all occupy the space once held by deities, angels, demons, spirits – beings of superior intelligence and power who observe us, who might engage with us, who possess knowledge and abilities we lack. While these entities dwell in different realms, or lokas, the modern mind accepts the same proposition when articulated as different dimensions, or parallel universes, etc. And they appear to us in lights and crafts that defy earthly physics, like the divine chariots of Sūrya or Zeus. They represent hope that we are not alone in a cold, meaningless, and apathetic universe. That there are indeed other minds out there, and that consciousness pervades more dimensions of the cosmos than we can even perceive, or measure.

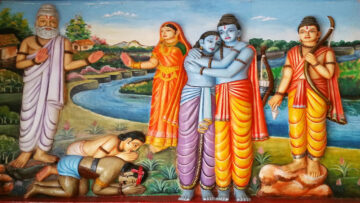

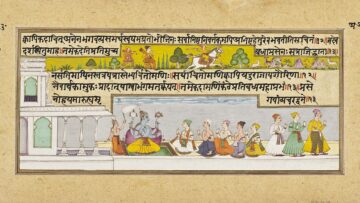

The technological vocabulary simply makes these beliefs more palatable to the modern mind. They can then be discussed in scientific journals, debated using probability theory, speculated on in hip podcasts, and hopefully – investigated with empirical methods. In other words, the modern world has not abandoned its need or yearning for contact with higher realms, it has simply reframed them in a more acceptable taxonomy. And so where one culture may speak of bhūtas, pretas, piśācas, gandharvas, yakṣas, pitṛs, rākṣasas, asuras, gaṇas, and devatās; another excitedly paints a landscape of aliens, extra-terrestrials, post-human time travellers, and the like.

Modern Myths, Ancient Myths

Long before the technological language however, the modern man had begun to realize the absence of magic and myth in his life. And so we find vivid examples of modern mythology – presented in literature as “fiction” but serving the same purpose, often by design.

Middle-earth; Westeros; A Galaxy Far, Far Away – these have become a sacred geography for millions. People name their children after characters from these stories, collect and preserve merchandise with religious fervence, make pilgrimages to filming locations as if they were sacred, and engage in heated theological debates about canon and interpretation. The tales of Tolkien and Lucas provide something the modern West desperately lacks – a coherent symbolic universe where good and evil have clear meanings, where individual actions matter cosmically, where magic remains real, and the numinous pervades existence.

Tolkien, most of all, understood exactly what he was creating. A devout Catholic and a scholar of medieval literature, he recognized that modernity had left England myth-starved. The ancient stories – Eddas, the Arthurian tales, the Celtic and Germanic traditions – had been relegated to academic study and stripped of their living power. Tolkien deliberately crafted a mythology for England, complete with creation story, a pantheon, heroic ages, and teleological prophecy. He was giving back to his people something they had lost – a world where the spiritual dimensions of existence remain visible and primary.

And that these modern myths successfully fill the void, speaks to the enormous cultural power of myth. They provide us with stories to orient us in cosmos and society, narratives that embody values and meaning, and worlds where the fundamental questions of existence find symbolic expression. The superhero phenomenon extends the pattern further. Comic book characters now dominate global popular culture – the likes of Batman, Superhero, Iron Man may well be modern deities. And they descend from older hero traditions and archetypes – Beowulf, Achilles, Arjuna, Sigurd, and more. But there is a difference in the register.

Ancient heroes operated within a cosmos saturated with meaning, where deeds resonated across the realms, gods watched and intervened, and the boundaries between human and divine were permeable. Their stories emerged from oral traditions rooted in particular peoples and places, carrying the wisdom and values of these cultures across generations. They were embedded in a living mythological and religious context. But modern superheroes are intellectual property created by committees, optimized for mass marketing across demographic categories. They inhabit universes that multiply, spin-off, and reboot – death loses permanence and continuity exists in fan service. Their stories unfold now in visual media calibrated for spectacle, instead of the verse, prose, play, and song that characterized the old world. And they operate in a cosmos resembling the modern – broadly materialist, scientifically explicable, devoid of deep enchantment.

This tells us what modern myth-making can and cannot accomplish. Superheroes do provide the thrill of powers beyond the human, and the satisfaction of justice served. They offer power fantasies to the disempowered, and wish fulfillment for the frustrated. But they do not connect us to anything genuinely transcendent. Their mass consumption reflects the modern yearning, but they are fundamentally entertainment products in a capitalist modernity. In contrast, the ancient hero’s journey involved encounters with gods, descents into the underworld, and a navigation of fate, order, rule, and destiny. These elements directed the stories toward metaphysical realities and quenched humanity’s thirst for transcendent engagement.

The difference is a poverty of the materialist worldview attempting to generate myth. Ancient myths emerged from cultures that lived alongside magic and divinity, where events in the material world were ripples from a higher-order reality, and the film separating material and spiritual was thin. The modern substitution of this imposes a tragic cost. Ancient people lived in relationship with their landscape, ancestors, spirit and guardian deities, seasonal cycles, and more. They participated in a cosmos ordered by ṛta, and responded to it through ritual and prayer, through human dharma. This connected them to other dimensions of reality, beyond the purely physical. And the participation elevated them through divine encounters.

But modern myths exist within a clinical frame, offering myth-shaped objects that lack the living core. And the modern human, cut from ancient roots, experiences existence differently. The world becomes a collection of resources to exploit, and other creatures are diminished to biological machines. The dead vanish into absolute absence – they don’t join their ancestors on a different plane of existence. And time, divine time with its cycles and ripples, is flattened into a linear progress. The result is a profound loneliness of the human psyche, and isolation of our consciousness in a mute universe of matter. But in our dreams, we see the same colors and forms, only labelled in the language of our modern, technological world.

So, we create substitutes that provide some solace from the isolation – technological transcendence, hyper-scientific futurism, franchise mythologies, superhero pantheons. It’s an acknowledgment of our primal hunger, even if these creations do not truly satisfy it. They represent a rebellion of the psyche against a worldview increasingly too narrow to contain human experience in its fullness and richness.

Many Hues of the Grasping

Interweaving with the modern theories and myths that grasp for ancient intuitions is the rise of indigenous wisdom traditions, psychedelic spirituality, neopaganism, and other attempts to recover pre-modern modes of consciousness. Those subscribing to these have sensed that something vital has been lost. That the rationalist-materialist paradigm, for all its technological achievements, has impoverished human life in ways that matter profoundly. The question facing us is whether genuine re-enchantment is possible, or whether we can only generate facsimiles and cargo cults of transcendence.

Can modern humanity, so thoroughly rationalized and commodified, recover its lost relationship with numinous transcendence? Or will it remain haunted by the ghosts of meaning, constructing elaborate simulations of the spiritual world our ancestors inhabited as naturally as breathing? When the late Terence McKenna was asked for his opinion on the coming world of virtual realities, and whether it would be possible to recreate the psychedelic experience by VR, he replied (paraphrased)-

“Why create an artificial version of the psychedelic experience when we have the psychedelic experience? And we know that the synthetic versions that will replace the real, will be used to sell us more crapola, more gratuitous violence, more pornographic denigration of women.”

What he expressed holds true for the spiritual dimension as well, even with our modern technologies and mythological fiction universes. And the pathways we take in the future matter. Humans who feel part of a living cosmos, connected to ancestors and descendants, embedded in relationships with non-human entities, grounded in mythologies oriented to the sacred – tend to live differently than the card-carrying materialists. They show greater restraint toward nature, more reverence for life, more concern for long-term consequences, a greater ability to be content, and a higher resilience for the suffering inherent in life. They experience meaning and purpose more readily, and suffer less from the alienation and despair that plagues modern, secular societies. Absent all of this, we create a modern reality pervaded with absurdities – like a civilization that celebrates World Environment Day even as it considers the “forest and tree worship” of indigenous tribes as primitive superstition.

So, the choices we have made – the monotheistic divorce from living divinity, the reduction of Judeo-Christianity itself to rationalized theology stripped of mysticism and magic, the embrace of materialist explanations as the only form of knowledge, the religious devotion to technology as humanity’s messianic saviour – these choices have cosmic costs. They shape how we inhabit the world, and how we understand our purpose and place in it. Those of us with skeptical, rationalist, and atheistic dispositions may yet insist on the famous quip by Douglas Adams-

“Isn’t it enough to believe that the garden is beautiful, without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”

To which the response has now become increasingly clear – those asking such a question have themselves answered it. By believing not in fairies, but aliens from the planet Nibiru visiting the garden from time to time. By believing not in an ultimate creator of that garden, but in a simulator hyper-race somehow tending the garden from outside it. By dismissing magic in the garden’s soil while theorizing on the stranges, charms, ups, downs, and dark matter powering the soil nonetheless. By relegating the stories of those that once inhabited the garden as primitive myth, while painting new heroes and epics onto the same palimpsest.

And what remains certain is that the human need for magic, for connection to transcendent dimensions of reality, for active participation in a cosmos alive with meaning – these will not disappear simply because we have declared ours to be the age of Reason. It will find its outlets, whether in ancient forms recovered, new forms invented, or strange hybrids of both that our descendants would barely recognize as spiritual at all. Which of these roads we take will determine whether the schism in the modern psyche is amicably resolved, or takes humanity deeper down a fundamental divorce from its own essential nature.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author. Indic Today is neither responsible nor liable for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in the article.